Set on Bourbon Street in the late 1950s, the Elvis Presley vehicle King Creole—the featured title for the June 7 #NolaMovieNight—features a variety of musical styles performed in a variety of venues (most re-created on sets at Paramount Studios in Los Angeles). In this First Draft post, Eric Seiferth, Curator/Historian at The Historic New Orleans Collection and co-curator with THNOC’s Alfred Lemmon of the exhibition New Orleans Medley: Sounds of the City, surveys the Bourbon Street music scene of the era.

Listen while you read, with this Spotify playlist assembed by Seiferth:

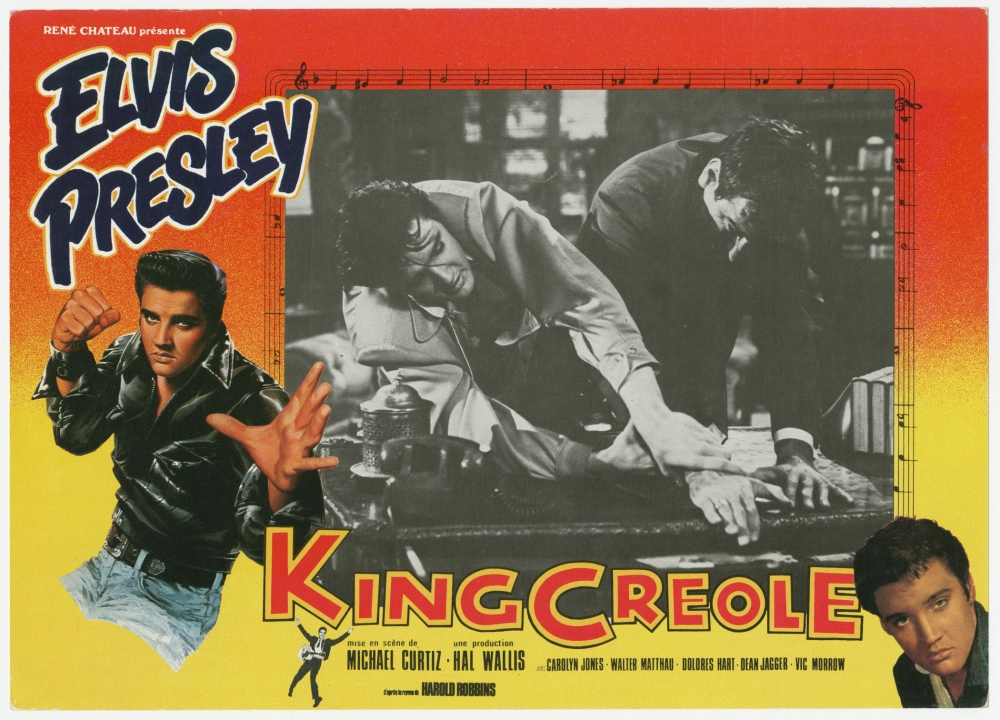

Elvis Presley starred in the 1958 film King Creole, set in New Orleans. In this First Draft feature, we ask THNOC Curator/Historian Eric Seiferth if the Bourbon Street in the movie was anything like the real thing? (THNOC, New Orleans and Louisiana in Film Collection, 2014.0102.74)

Elvis Presley starred in the 1958 film King Creole, set in New Orleans. In this First Draft feature, we ask THNOC Curator/Historian Eric Seiferth if the Bourbon Street in the movie was anything like the real thing? (THNOC, New Orleans and Louisiana in Film Collection, 2014.0102.74)

Q: What did Bourbon Street or the larger French Quarter sound like in the time period depicted in King Creole, released in 1958?

A: Bourbon Street in the 1950s was a thriving entertainment district, with a number of clubs for music, burlesque, and dancing. During this era, tourism was steadily increasing, both in numbers and as a citywide economic initiative, and Bourbon Street was a part of this effort. Because of this, Bourbon Street of the 1950s catered in large part to visitor entertainment. During this era, much of the music could have been described as Dixieland. Exactly what Dixieland music is is a debate in itself, but it’s safe to say there was a large presence of New Orleans jazz music on the strip. That’s not to say that Dixieland was the only music played on Bourbon in the 1950s, as we know that a number of early R&B performers played on the street during these years as well, including Smiley Lewis, Tommy Ridgley, Tuts Washington, and Clarence “Frogman” Henry who played at the 544, Court of Two Sisters, and La Stratta—all on Bourbon—for much of the 1950s and 1960s.

Barrelhouse and blues were popular styles on the strip, usually played by small combos, and typically featuring a piano. This music was, in many ways, a stop on the path to rhythm and blues and rock ‘n’ roll. The blues song “Junker’s Blues,” for example, was popular in French Quarter clubs as early as the 1940s. New Orleanian Champion Jack Dupree recorded the song on the Okeh label in 1941, and barrelhouse pianist Kid Stormy Weather was known to have performed it alongside Harrison Verret in the Quarter during the same era. Verret is possibly better known as Fats Domino’s uncle, and “Junker’s Blues” is certainly better remembered as “The Fat Man.” This music was around, even on Bourbon during the 1950s, though it would have been the outlier to the more popular Dixieland. Some of the well known jazz and Dixieland performers on Bourbon in the 1950s included Louis Prima, who led the band at the Sho Bar for a time, and Pete Fountain, who was at a number of clubs for much of the decade.

Bourbon Street of the 1950s featured Dixieland, jazz, R&B, blues, and other types of music. (THNOC, gift of Eugene C. Major, 1990.135.8)

Bourbon Street of the 1950s featured Dixieland, jazz, R&B, blues, and other types of music. (THNOC, gift of Eugene C. Major, 1990.135.8)

Beginning as early as the 1930s and into the 1940s, a number of blues singers and piano players were performing on and around Bourbon Street. Artists such as Tuts Washington, Smiley Lewis, and John Leon Gross (who performed and recorded as “Archibald”) performed repertoires that combined blues, jazz, and barrelhouse—sometimes with combos, and sometimes as solo acts. Washington and Lewis played together as early as the 1930s. It was during these years when Lewis developed his rhythm-and-blues style heard on his 1950s Imperial hits such as “Tee Nah Nah” and “I Hear You Knockin’.” Archibald, meanwhile, spent a number of years performing at the Magic Lock Cocktail Lounge before moving on to Poodle’s Patio Bar in the 1960s, both clubs located on Bourbon Street. His 1950 Imperial release “Stack-A-Lee” was a national hit, reaching No. 10 on the Billboard national R&B chart. Another pianist, Walter “Fats” Pichon, spent years as the house musician at the Old Absinthe House. Pichon was known for playing a variety of popular melodies—which would have ranged widely from jazz to blues numbers and much in between—and boogie-woogie hits.

Though Bourbon Street was just a few blocks from rock 'n' roll Ground Zero (J&M Recording Studio), would examples of that new genre have made any inroads into those clubs?

Many of the musicians who performed on Bourbon Street during this era also cut albums at J&M Recording Studio on Rampart and Cosimo Recording Studios on Governor Nicholls. In this way, the 1950s marks something of a turning point in the music scene in the Quarter generally, and on Bourbon more specifically. It is around this time that “guitar bands,” as they were often disparagingly referred to, started performing more often, to the detriment of Dixieland and traditional jazz bands. It is no coincidence that Preservation Hall opens in 1961, with a mission to preserve jazz in the French Quarter. This illustrates how musical tastes and styles were changing on the strip.

An all-black band is shown playing at the Paddock Lounge. The Paddock was known for featuring more black musicians. (THNOC, the Richard R. Dixon/Cole Coleman Collection, gift of Mr. & Mrs. Richard R. Dixon, 1980.257.10)

In 1958, we're still a few years away from the Preservation Hall revival of traditional jazz. Was there much jazz on the street?

Absolutely. And Dixieland too. The traditional jazz revival really begins in the 1940s. This is when the publication Jazzmen was released, and when jazz scholar/musician/collector Bill Russell started recording people like Bunk Johnson and George Lewis. It’s during these years that a number of second-generation traditional New Orleans jazz musicians start playing regular gigs on the strip. People like Oscar "Papa" Celestin, Lewis, and the Humphrey brothers were known to perform at the Paddock Lounge and Mardi Gras Lounge clubs a decade or more before Preservation Hall even opened. Preservation Hall certainly played a role in keeping the music and tradition alive, but the Hall came along on the back side of the revival, or maybe its second wave.

Oscar "Papa" Celestin's band is shown performing at the Paddock Club on Bourbon Street in June of 1950. (THNOC, William Russell Jazz Collection, 92-48-L.331.1695)

What role did live music play in burlesque clubs?

Bourbon Street was filled with music clubs during the 1950s. It was one of the city’s more active musical streets. Clubs lined the strip and provided a variety of offerings, though Dixieland predominated. The music was for dance clubs, piano bars and, yes, burlesque performances as well. And, often, for all of the above at the same club on the same night. Some musicians would start their shift playing behind a dancer, and then go back on stage for a late-night, music-only act. These clubs stayed open late and had live music all evening and all night long—that takes a lot of performers and makes for a wide variety of styles. And consider, you may not want to hear the same type of music at 8 p.m. as you would during a burlesque show at 11 p.m. or while winding down after-hours at 2 a.m. So, many venues included multiple styles over the course of a single evening. (To learn more about burlesque on Bourbon Street, read Nina Bozak's First Draft article on Stormy Lawrence and the Casino Royale.)

In one scene in King Creole, the character played by Elvis Presley jumps on stage to perform with an African American band. Would such a performance have been possible in 1958?

Yes, this would have been possible, but also would have been an arrestable offense, likely filed under “disturbing the peace.” Interracial performances were not allowed during this era, and there were plenty of instances of musicians receiving rough treatment and penalties from the police and the judicial system for playing together. It was just not tolerated by law enforcement and most club owners. As a result, clubs during this era would have either included mostly black musicians—such as the Paddock and Mardi Gras Lounge, which leaned toward more traditional New Orleans-style jazz—or white bands. The Famous Door, for example, was known as a place to hear white Dixieland bands, regularly featuring The Kings and, later, Dukes of Dixieland.

The Famous Door lounge was known for featuring white Dixieland bands, such as the one shown here circa 1960. (THNOC, the Richard R. Dixon/Cole Coleman Collection, gift of Mr. & Mrs. Richard R. Dixon, 1980.257.11)

Segregation was in full force in New Orleans during the 1950s, and that was the case on Bourbon Street as well. African Americans were not welcome on the strip or in the establishments as patrons—nor were they able to to walk down the street itself without harassment. Nevertheless, many of the workers and musicians on Bourbon were black, and much of what was being sold on stage was commodified black culture—think rock ‘n’ roll and jazz for example. African American musicians who worked on the strip during the era often talk of having to enter clubs via back doors, and being forced to take breaks in back rooms and off side streets. Bourbon Street was not a friendly place for African Americans during much of the 20th century. This was a place the city was selling to visitors from across the country, and there was a real fear among business leaders and city officials that anything upsetting the strict Jim Crow social order would potentially damage profits.