This story is released in conjunction with The Historic New Orleans Collection’s 2021 Symposium, “Recovered Voices: Black Activism in New Orleans from Reconstruction to the Present Day.” The interactive website includes books, stories, videos, and a March 5–7 program. Learn more by following the link in the box below.

“We ask that, in reconstruction of the State Government [in Louisiana], the right to vote should not depend on the color of the citizen; that the colored citizen shall have and enjoy every civil, political, and religious right that white citizens enjoy; in a word, that every man shall stand equal before the law.” —E. Arnold Bertonneau, 1864

In February 1864, two free men of color traveled from New Orleans to Washington, DC. It was a risky journey to take in wartime, but former Union Army Captain E. Arnold Bertonneau and newspaper publisher Jean-Baptiste Roudanez had a mission.

As the chosen “Delegates of the Free Colored Population of Louisiana,” the men were tasked with presenting a petition to President Abraham Lincoln and Congress requesting the right to vote. The petition, with over 1,000 signatures, argued for free Black participation “in establishing a civil government in our beloved State of Louisiana.” An addendum to the petition expanded the call for suffrage “to all others, whether born slave or free . . . subject only to such qualifications as shall equally affect the white and colored citizens.”

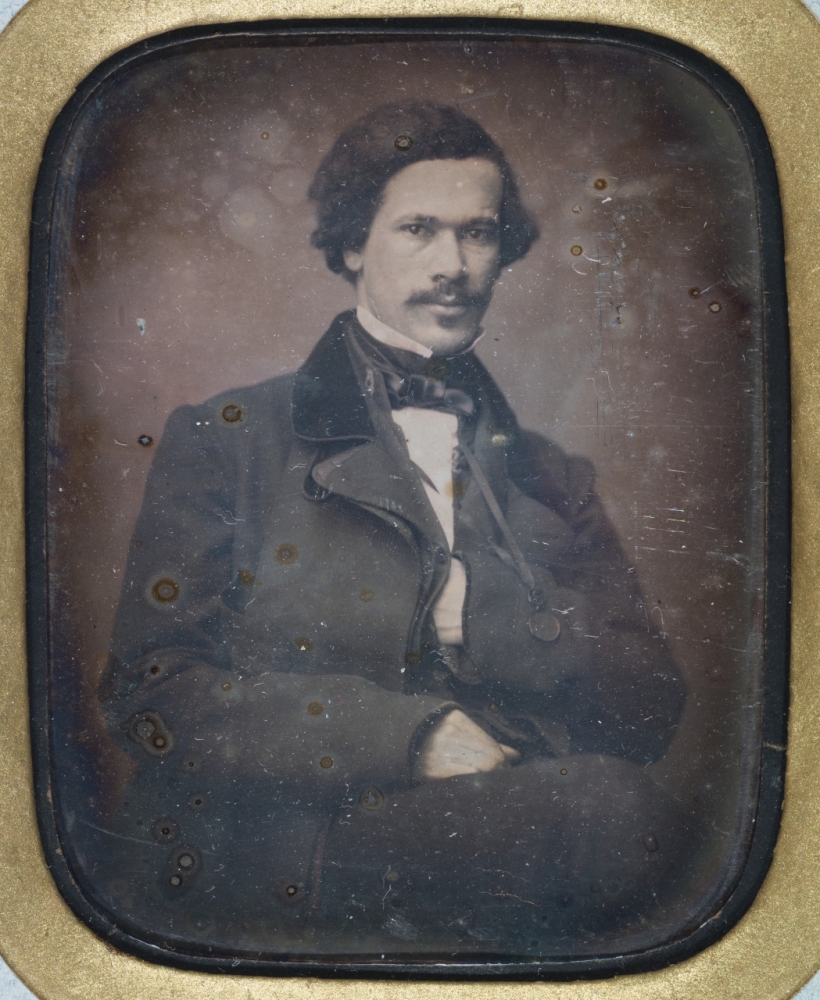

A circa 1857 portrait shows Louis-Charles Roudanez, whose brother Jean-Baptise visited Washington, DC, to petition for voting rights. (THNOC, gift of Mark Charles Roudané, 2017.0201.1)

The meeting of two French-speaking New Orleanians of African descent with the president of the United States represented a significant step in a growing civil rights movement. Bertonneau and Roudanez were part of a cadre of Creole activists who understood the Civil War as a revolutionary moment.

They envisioned a future without slavery, in which all men were treated as full and equal citizens, and they understood the franchise as a foundational right on which this vision could be built. Between 1862 and 1868, Creole leaders allied with English-speaking free men of color and white Unionists to advocate for universal manhood suffrage. Local circumstances shaped Black New Orleanians’ successful struggle for the vote, but their fight had far-reaching consequences.

When Union forces took command of New Orleans in 1862, free Black activists perceived a changed political landscape. They seized the opportunity to prove their loyalty to the United States, assert their views on equality and citizenship, and participate in the building of a new government.

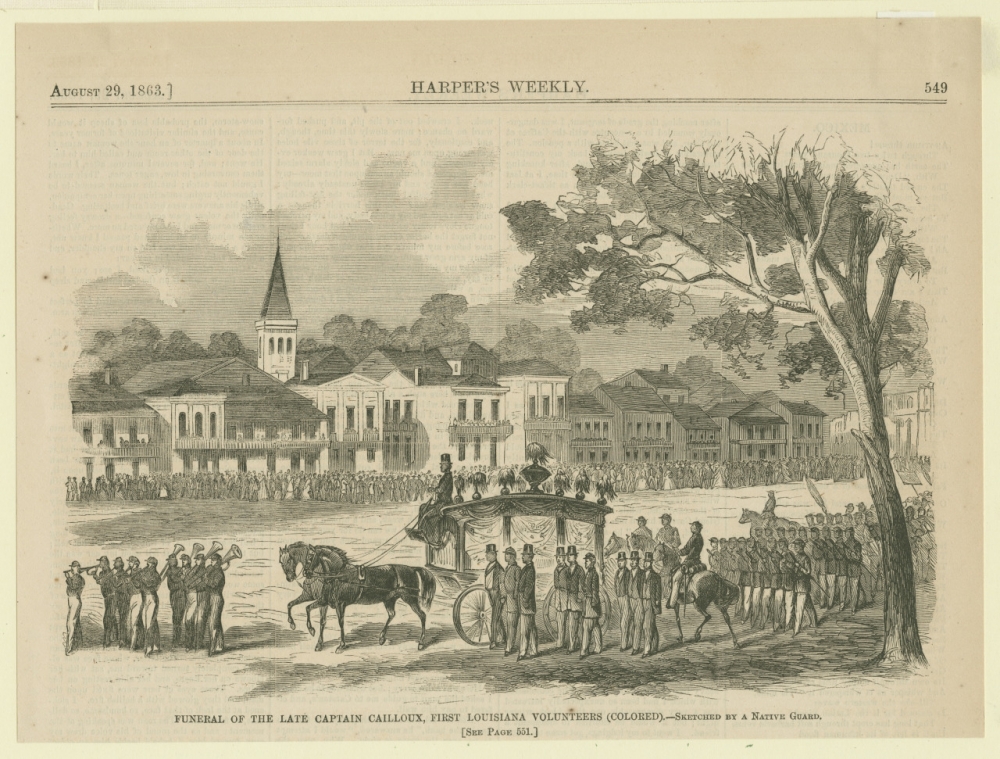

Creole leaders immediately pressured General Benjamin Butler to enlist free men of color into the US military. The first of three regiments, which included free Black officers, mustered into the army on September 27, 1862. Black soldiers and their supporters viewed their military service as proof they were citizens who deserved full political rights.

This 1863 illustration depicts the funeral of Captain Andre Cailloux, a Black officer in the Union army who fell at the Siege of Port Hudson, Louisiana. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1958.43.3)

Creoles also developed a newspaper to espouse their ideas and rally supporters to their cause. The same day of the first regiment’s muster, Jean-Baptiste Roudanez, his brother Louis-Charles Roudanez, and editor Paul Trévigne launched L’Union.

The newspaper provided a public platform to argue for the inclusion of Black men as active and equal participants in the creation of a new society—one that fulfilled the nation’s founding ideals of freedom and equality. In articles, editorials, and poetry, L’Union called for the abolition of slavery, equitable treatment of Black soldiers, and the right to vote.

Creole activists paid close attention to white Unionists’ attempts at collaboration with military officials to form a new state government that would bring Louisiana back into the Union. They formed connections with Thomas Durant, the white progressive leader of the Union Association. This relationship deepened over 1863.

In July of that year, the Union Association named L’Union its official French-language publication. More importantly, free men of color pushed their white allies to become more progressive. Durant, who was named attorney general and tasked with registering “loyal citizens” to vote, shifted his support from a new state constitution that merely abolished slavery to one that also enfranchised free men of color.

As Creoles built relationships with white supporters, they also formed closer ties with leaders in the English-speaking free Black community, setting aside cultural differences in favor of racial solidarity. The treatment of Black soldiers by Butler’s replacement, General Nathaniel Banks, assisted this alliance: Banks reduced recruitment of Black soldiers and forced free officers of color to resign, even as they proved themselves on the battlefield. These actions fueled free people of color’s collective efforts for full political rights. Officers discharged by Banks, like Arnold Bertonneau and P. B. S. Pinchback, became outspoken advocates for Black citizenship and racial equality.

Black officers discharged by General Nathaniel Banks, like P. B. S. Pinchback (above), became outspoken advocates for Black citizenship and racial equality. (THNOC, 1974.25.27.354)

On November 5, 1863, this coalition of French- and English-speaking free Black activists and white Unionists came together at a forum on Black voting rights. Over 600 people packed into the headquarters of the Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle, an organization to which a number of Creole activists belonged.

The meeting began with white Unionist speaker Josiah Fisk, who argued that free men of color should wait until the new civil government was formed to press for suffrage. “We have waited long enough,” replied Economie member and L’Union contributor François Boisdoré. In a powerful rebuttal to Fisk’s call for patience, Boisdoré reasoned, “If the United States has the right to arm us, it certainly has the right to allow us the rights of suffrage.” He then declared, “If we cannot succeed with the authorities here . . . [w]e will go to President Lincoln.”

The headquarters of the Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle, an organization to which a number of Creole activists belonged, is shown here in the 1930s. (THNOC, William Russell Jazz Collection, 92-48-L.331.133)

The arguments made by Boisdoré and other free Black speakers convinced Durant to pledge the Union Association’s support for voting rights for free men of color; however, appeals to military officials to allow them to register went nowhere.

December brought a more serious setback. Lincoln announced his reconstruction plan for Louisiana, which limited the electorate to white men who voted in 1860. With elections for new government officials and delegates for the state constitutional convention scheduled for early 1864, free Black activists wasted no time. They gathered signatures for a petition to “go to President Lincoln” and raised money to dispatch Bertonneau and Roudanez to the US capital.

The delegates met with Lincoln in early March. The president expressed sympathy for the men’s positions, but he did not believe he had the power to fulfill their request unless it was a “military necessity.” Yet the petition did influence Lincoln’s thinking. After the meeting, he wrote to the newly elected Louisiana governor Michael Hahn with the suggestion that Hahn privately consider enfranchising “some of the colored people.” Lincoln made a similar statement in his last public address in 1865.

Although the delegates’ consultation with Lincoln did not produce the hoped-for results, the bold actions of Bertonneau and Roudanez and the men they represented in New Orleans brought the issue of Black political equality to national attention. While in Washington, the two men found allies on the suffrage issue in Republican Congressmen Charles Sumner and William Kelley.

Bertonneau and Roudanez then traveled to New York and Boston, where they met with members of the Black press and leading abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. The New Orleanians’ tour brought the subject of Black voting rights to the fore of a national conversation about reconstruction.

Back in New Orleans, the suffrage fight continued to meet resistance. Governor Hahn did not follow up on Lincoln’s proposal, and the 1864 constitution limited suffrage to white men. L’Union shut down in the face of threats and financial struggles. Rather than give up, the Roudanez brothers and Trévigne started a new paper, the New Orleans Tribune, with a staff that reflected a coalition of Creole, Black, and white activists.

An 1866 front page of the Tribune appears in French. The newspaper was also published in English. (THNOC, gift of Karl Kabelac, 2003.0280)

The Tribune became the voice of a full-fledged civil rights movement. While voting rights for all Black men remained a central goal, the editors expanded their demands to include equal access to public accommodations, transportation, and schools along with land redistribution, fair wages, and other protections for Black workers. Printed daily, the bilingual publication found wide readership across New Orleans, to the halls of Congress, and beyond the United States.

When the war ended in 1865, Tribune leaders partnered with Thomas Durant to create the Friends of Universal Suffrage. The interracial political association expanded its coalition by joining with the more moderate National Union Republican Club to become the Republican Party in Louisiana. The new organization urged the national party to place Black voting rights at the center of its platform and held a parallel election to prove the power of an inclusive electorate to Republicans in Washington.

The results of the actual elections, however, brought the return of former Confederates to power as conservative Democrats. The state legislature immediately passed laws to control the lives and labor of formerly enslaved men and women. President Andrew Johnson’s lenient reconstruction plan sanctioned these actions.

In response to these developments, white Unionists and Republicans devised a plan to reconvene the 1864 state constitutional convention to grant Black men the right to vote. It was a risky strategy that ultimately led to violence.

On July 30, 1866, Republican delegates met in the Mechanics’ Institute meeting hall to open the constitutional convention. A parade of Black Union veterans and other supporters marched to the building. Upon their arrival, the all-white police force launched an attack on the supporters outside the Institute and the delegates inside. The brutal assault caused over 150 injuries and at least 45 deaths. Most of the victims were Black people.

An engraving from Harper's Weekly depicts the massacre at the Mechanics’ Institute on July 30, 1866. (THNOC, 1979.200 iii)

The Mechanics’ Institute Massacre was one of several violent events that led to the passage of the 1867 Reconstruction Acts, which included military rule and the creation of new state constitutions in the former Confederate states. Black men could participate in the constitutional conventions, and all new state constitutions had to include universal male suffrage. States also had to ratify the 14th Amendment, which established birthright citizenship and provided citizens equal protection under the law.

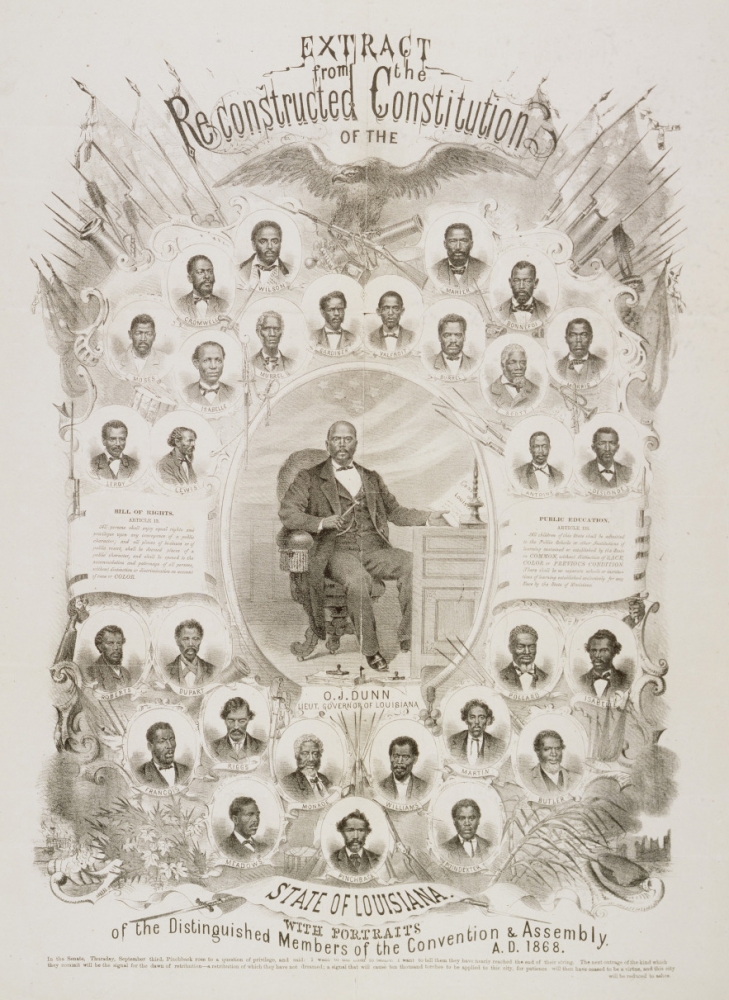

In September 1867, 83,000 Black men registered and voted for delegates to the constitutional convention. Half of the delegates selected were men of African descent, including activists Arnold Bertonneau and P. B. S. Pinchback. The Louisiana constitution was arguably the most progressive of all the Reconstruction-era constitutions.

In addition to giving Black men the right to vote, the 1868 constitution abolished discriminatory labor laws, explicitly guaranteed to all citizens the same “civil, political, and public rights,” and included measures that outlawed segregation in government buildings, private businesses licensed by the state, public transportation, and public schools.

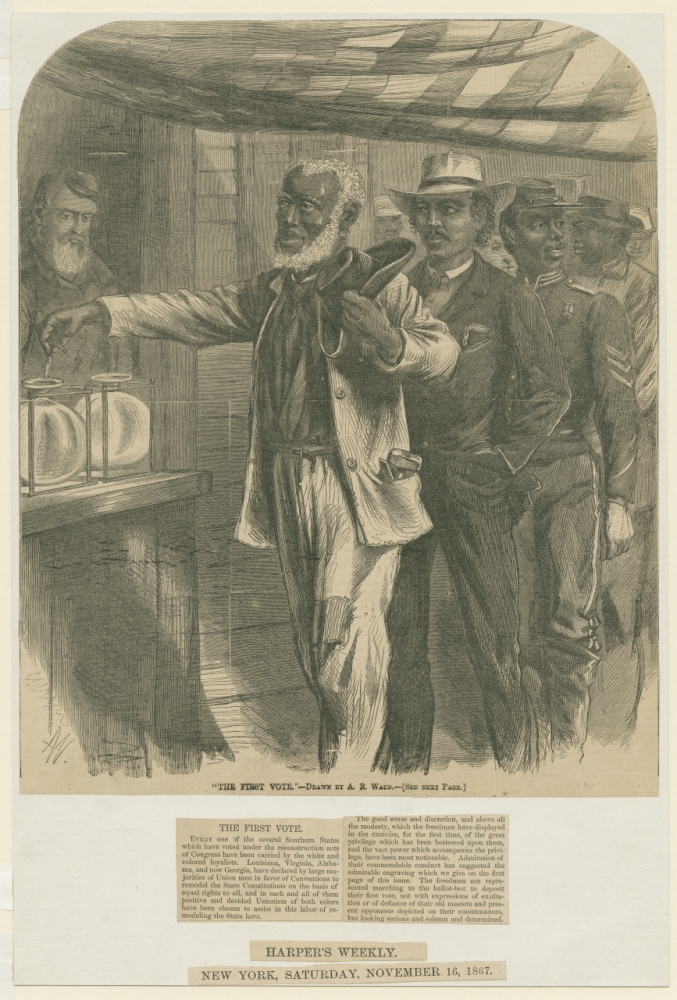

An 1867 illustration by Alfred Waud shows Black men voting in an election. (THNOC, 1974.25.9.319)

What began as a local struggle for the franchise became a national one. Through their organized actions and effective arguments, free Black New Orleanians encouraged white people in the city, in Congress, and throughout the nation to see beyond the abolition of slavery to the necessity of full citizenship and equal rights for all people of African descent.

These activists believed that race should not be a barrier to the franchise—an idea enshrined in the US Constitution with the ratification of the 15th Amendment in 1870.

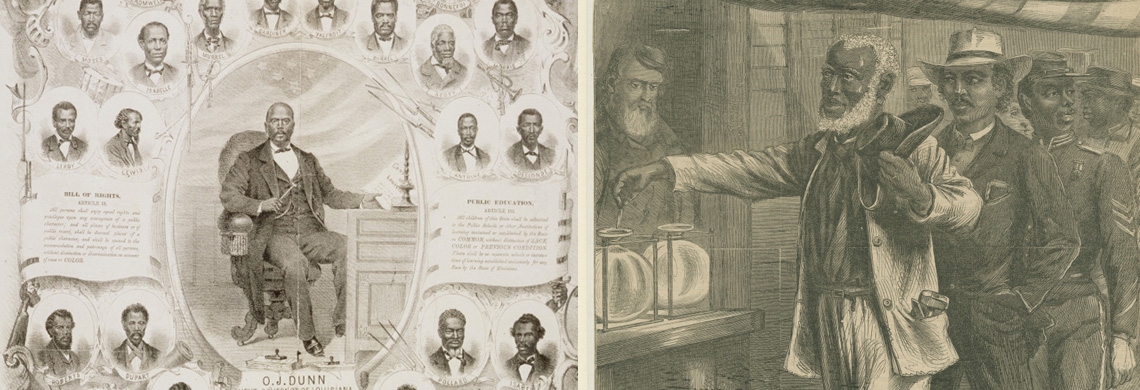

This commemorative lithograph depicts the African American men elected to public office in Louisiana in 1868, including Oscar J. Dunn, the first person of African descent elected lieutenant governor in US history. (THNOC, 1979.183)

Black Louisianians’ access to the ballot proved short-lived. By 1898 (twenty-eight years after the ratification of the 15th Amendment), white Democrats had consolidated power and successfully called for another state constitutional convention to “establish the supremacy of the white race.” The delegates passed several measures meant to disenfranchise Black men but skirt the 15th Amendment with devastating results.

In 1896, 130,344 Black men were registered to vote. That number dropped to 5,320 by 1900. It would take sixty-five years and another civil rights movement before the federal government took action to guarantee the franchise for Black Louisianians.

Explore Black activism in New Orleans through our Symposium 2021 website.