This story is released in conjunction with The Historic New Orleans Collection’s 2021 Symposium, “Recovered Voices: Black Activism in New Orleans from Reconstruction to the Present Day.” The interactive website includes books, stories, videos, and a March 5–7 program. Learn more by clicking the box below.

“The African race will now fight for all that is dear to man. The black and colored men will rise up throughout the land, not by thousands, but by hundreds of thousands and by millions.”—New Orleans Tribune, July 30, 1865

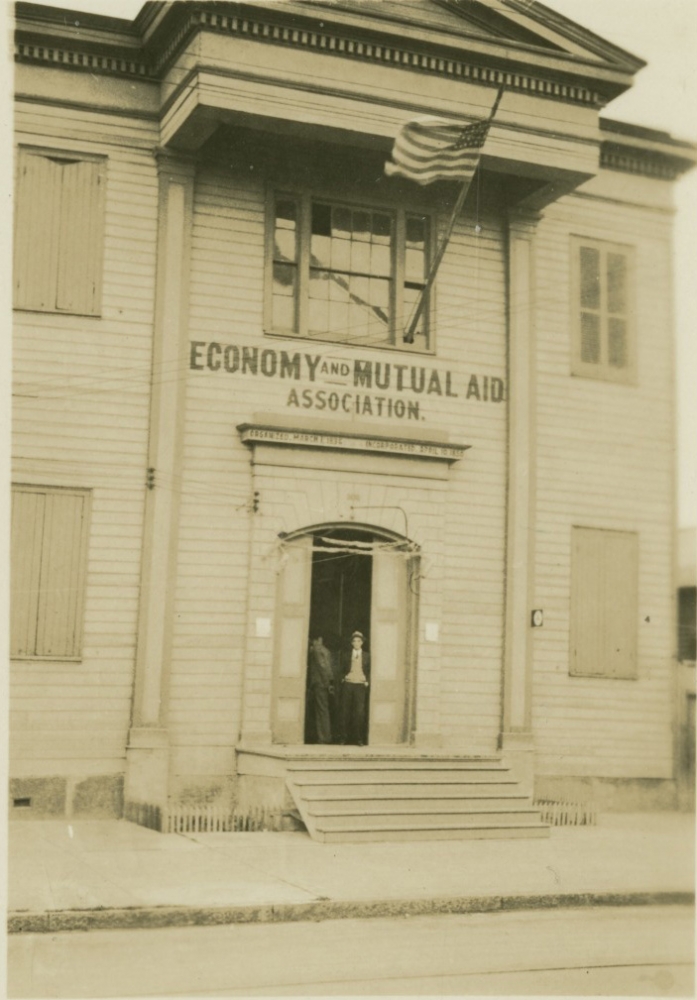

On December 20, 1857, a 21-year-old brotherhood called the Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle inaugurated its new meeting hall. Situated in the heart of the Tremé neighborhood, the society's hall would serve as a meeting place for Black activists and white allies intent on securing rights for all.

As its name indicates, the society was a French-speaking group, composed mainly of free Black Creoles—people of mixed African and European descent, many of whose families were at least a generation removed from slavery. In pre–Civil War New Orleans, many Black Creoles owned property, received formal educations—sometimes in France—and ran businesses across the city. They were versed in France’s history of revolution and that of its colonies; some of their ancestors had joined, or fled, the 1791–1804 revolution that won Haiti its independence from France.

The Economy Society’s meeting hall is pictured here in 1939, just over a century after the organization was first established. The hall served as a meeting place for activists throughout the Reconstruction period. (THNOC, William Russell Jazz Collection, 92-48-L.331.133)

Among their ranks was Ludger Boguille, a free man whose parents had come to New Orleans from Haiti decades earlier. Boguille’s activism started in education; well before the war, he broke the law to teach an enslaved person, and he continued to teach through the Civil War. During the war, Boguille and many other Economy Society members, inspired by French revolutionary ideals, began advocating in earnest for Radical Republican causes, including equal rights for Black people.

“The Economy Society members thought they deserved equal rights,” said Fatima Shaik, author of THNOC’s forthcoming book Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood. “They did not feel inferior to anyone despite the social position given to them due to their African blood. Some cited their fathers’ and their own military service as evidence of their loyalty as citizens.”

A City Less Creole by the Day

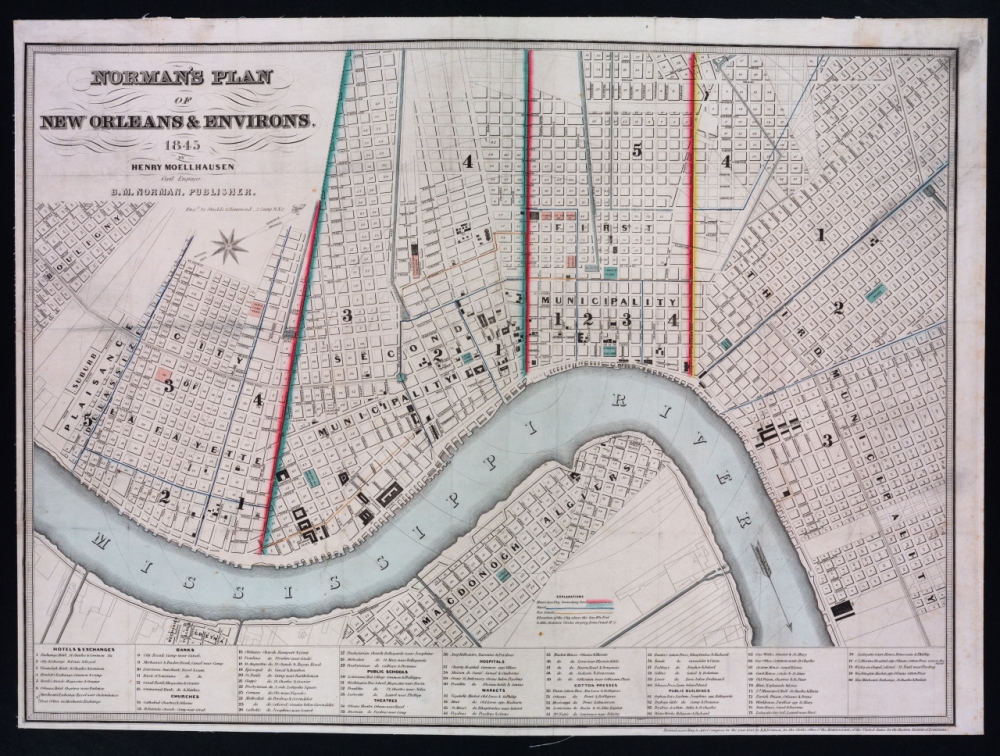

An 1845 map of New Orleans shows the city’s subdivision into three separate municipalities. Creoles, for the most part, resided in the First and Third Municipalities, downriver of Canal Street, while American transplants settled further upriver. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1949.7 a,b)

In a city that had been American only since the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, Afro-Creoles had clung to their French roots and lived a largely separate life from English-speaking Black Americans who came to Louisiana—the vast majority by force, through slavery. For decades, social integration between the city’s many demographic groups—Creoles, English-speaking Black Americans, white American migrants from the East Coast, and immigrants from other European countries—was spotty at best. In 1836, the city divided itself into three autonomous municipalities in part so that the English- and French-speaking populations could operate independently.

This demographic divide placed Creoles in the neighborhoods below Canal Street—Tremé, Faubourg Marigny, and the French Quarter—while white American migrants settled uptown, which became known as the American Sector. Free English-speaking Black people tended to live on the uptown side of Canal Street as well. But in the same year the Economy Society built its hall, the group accepted its first American member, a sign that these two distinct cultures could bridge that divide for common causes.

This late-1850s photograph by Jay Dearborn Edwards shows Canal Street, the rough dividing line between New Orleans’s American and Creole communities. (THNOC, 1982.167.2)

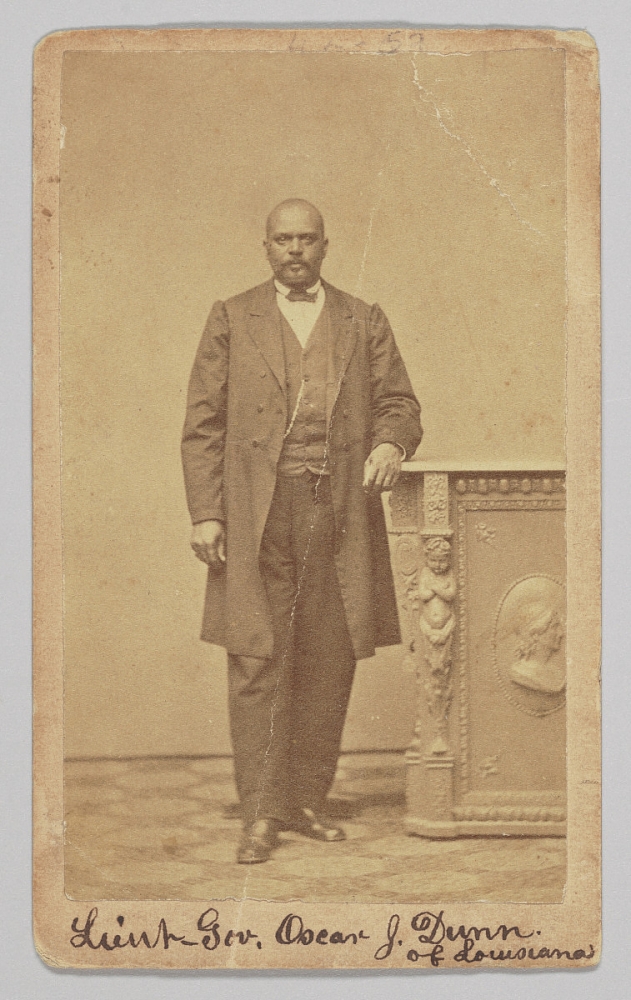

Oscar Dunn was unique among the Black leaders emerging in New Orleans. Emancipated at age 10 by his stepfather, he was a free Black American who spoke both English and French, having spent much of his early life in the city. He was a plasterer and had been a music instructor before the Civil War. He built ties with fellow English-speaking Black people through his masonic lodge, while connecting with French-speaking Creoles, like the members of the Economy Society, through other benevolent and political endeavors.

“Dunn crosses this imaginary line between the American and Afro-Creole community,” said Brian K. Mitchell, author of THNOC’s forthcoming book Monumental: Oscar Dunn’s Radical Fight in Reconstruction Louisiana. “He lived in Tremé, St. Mary [now the Central Business District], Marigny. He was very much an amalgamation of what New Orleans was at the time.”

This portrait taken between 1868 and 1871 shows Oscar Dunn, who was elected as Louisiana's Lietenant Governor in 1868—the first Black person elected to that position in US history. (Image courtesy of the Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture)

In the 1850s, though, white lawmakers in New Orleans and Louisiana worked to blur the distinctions between these Black communities, passing laws that limited the property ownership, travel, and vocational rights of all Black people. Then, in 1857, the US Supreme Court ruled in Dred Scott v. Sandford that the US Constitution did not grant citizenship to any Black people, free or enslaved, cementing the repressive binary already beginning to clarify in Louisiana.

Becoming American

The Union liberation of New Orleans in 1862 prompted a new wave of Black activism. This painting depicts the engagement between Union and Confederate forces on the Mississippi River below the city. (THNOC, 1974.80)

The Union liberation of New Orleans in 1862 prompted a new wave of Black activism. This painting depicts the engagement between Union and Confederate forces on the Mississippi River below the city. (THNOC, 1974.80)

In 1861, Louisiana’s dependance on slavery prompted the state to secede from the United States, but less than a year into the Civil War, Admiral David Farragut’s naval force won a decisive victory against Confederate battlements protecting New Orleans, the South’s largest city. White rebel forces fled before federal troops arrived, and the city surrendered quietly. For New Orleans’s free Black citizens—including some Creoles who had at first aligned themselves with the Confederacy—this regime change opened the door to a new wave of activism.

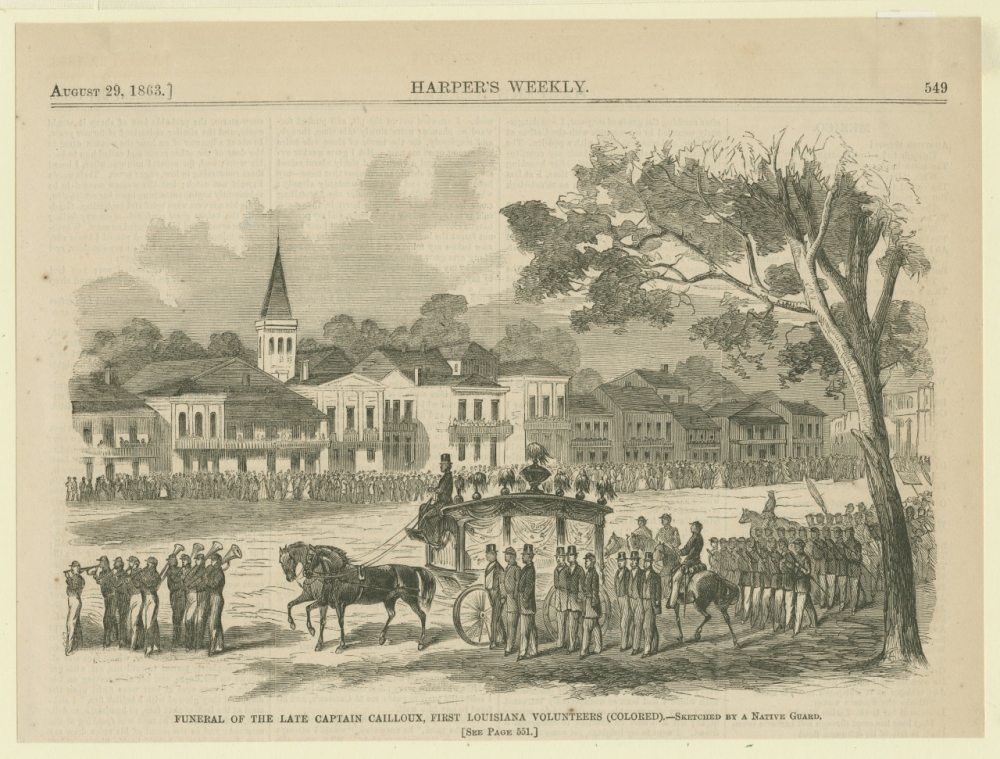

Following Union occupation, Black people lined up to enlist as soldiers in the Union army, an early sign of the patriotism that became a hallmark of Black political expression in the ensuing years. Following the heroic death of Black officer Andre Cailloux at the Siege of Port Hudson, Louisiana, a citywide funeral procession in July 1863 helped galvanize support behind the Union’s military cause—and the ideals of Americanism that the Supreme Court had denied Black people just six years earlier.

But the way that individuals viewed themselves as Americans varied greatly through language, education, and life experience.

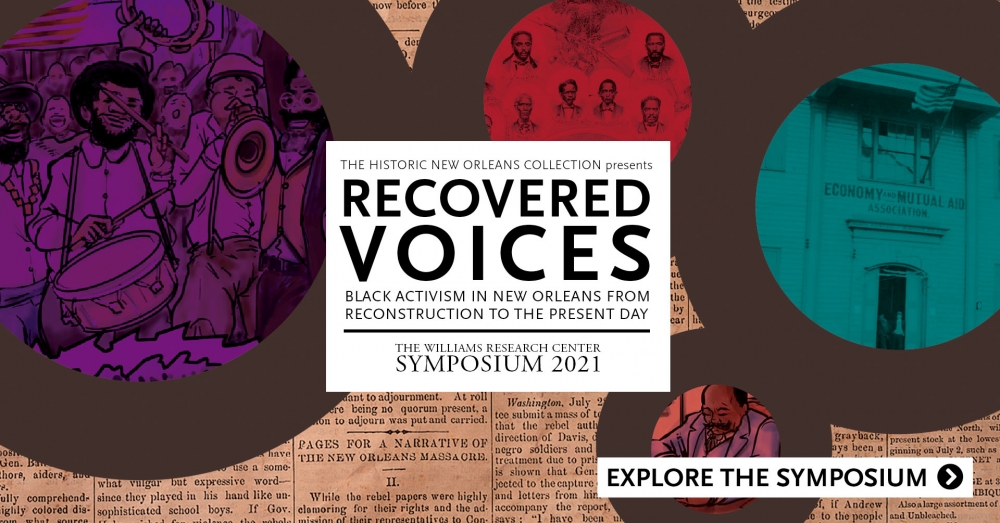

A Harper’s Weekly illustration depicts the funeral of Andre Cailloux, a major display of Black unity during the Civil War. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1958.43.3)

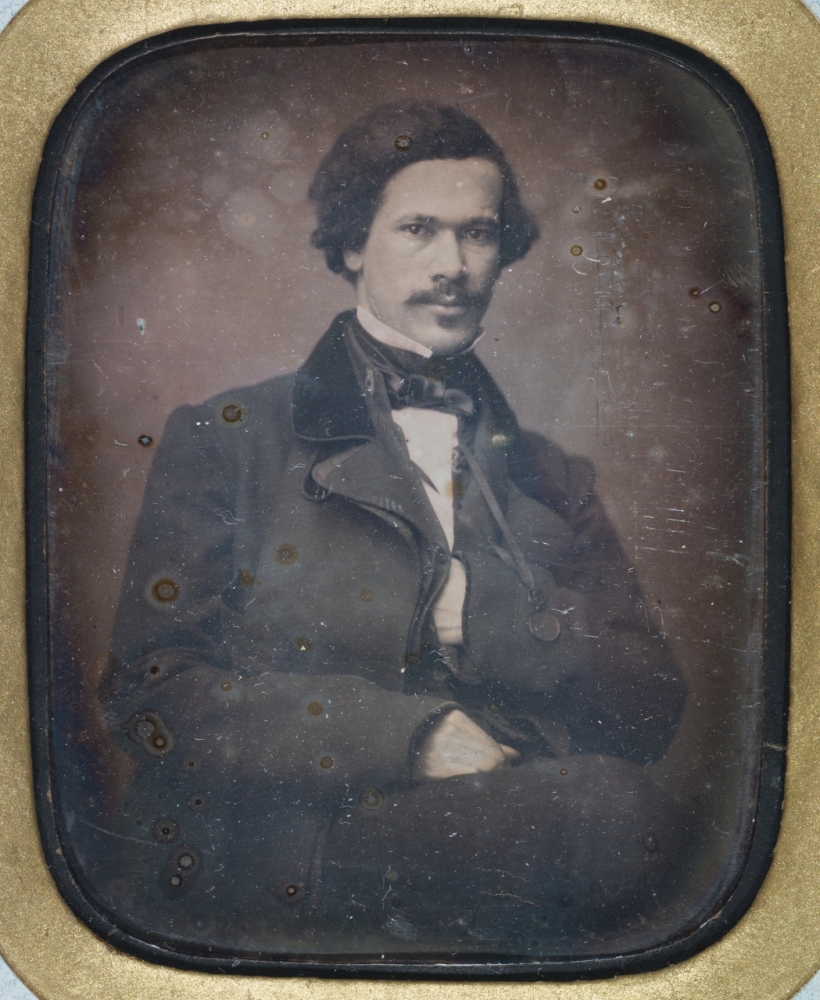

In 1862 New Orleans, Louis Charles Roudanez, Jean-Baptiste Roudanez, and Paul Trévigne founded one of Louisiana’s first Black newspapers, L’Union. Its pages—and its name—signified the growing fervor of American patriotism among a Creole community that had seen governments come and go in both Haiti and Louisiana. The paper’s first issue featured a copy of the US Constitution, translated into French for its readers.

The pages of L’Union and its bilingual successor, the New Orleans Tribune / La Tribune de la Nouvelle-Orléans, contained not only journalism and editorials but also poems penned by the city’s prominent Creole citizens, some of whom were members of the Economy Society. Writing in the style of French Romantic verse enabled them to advocate for emancipation and equal rights in language more idealistic and egalitarian than sometimes appeared in their prose. The French Revolution’s rights of man—liberté, egalité, and fraternité—are invoked throughout their poetry.

In one poem, titled “The South's Unending Rebellion” Adolphe Duhart wrote:

Do what we will, my lute can show no rage;

It preaches goodwill and sings fraternity;

To the oppressed, it says, “Brothers, stand in courage,

The hour soon will toll; we must save liberty!”

“I see the poetry as a vehicle for these French-speaking writers to work toward their Americanness,” said Clint Bruce, author of the recently published Afro-Creole Poetry in French from Louisiana’s Radical Civil War–Era Newspapers. “These French ideals were the only way they could imagine themselves as Americans, because there was no model for Black people being Americans, as full citizens.”

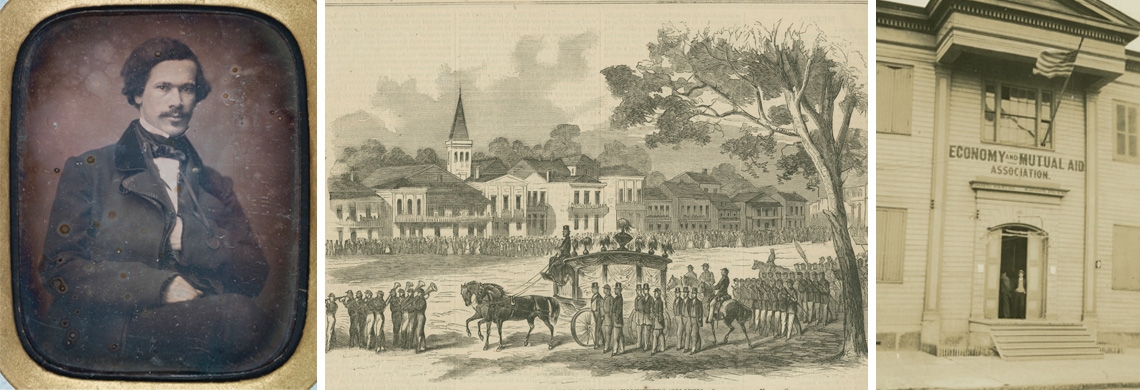

Louis Charles Roudanez is pictured here in 1857, six years before he co-founded L’Union. (THNOC, gift of Mark Charles Roudané, 2017.0201.1)

Unlike his Creole counterparts, Oscar Dunn’s sensibilities were squarely American. He believed in integrated government and public accommodations, but when it came to private life, he saw the preservation of Black-run businesses and social organizations as essential for progress. He viewed solidarity within Black institutions such as churches and Masonic lodges as a pathway toward social and economic empowerment.

“Dunn’s outlook was almost uniquely American,” said Mitchell. “He thought that for Black people to build wealth, they had to build their own financial institutions and their own businesses. . . . Had people understood what Dunn was trying to do and embraced it, it could have resulted in something like a Black Wall Street.”

From Community to Politics

In 1863, activists both Creole and American gathered at Economy Hall, which had become a hotbed of activity and debate during Union occupation.

The highlight of the meeting was a rousing speech by François Boisdoré in which he laid out the argument for suffrage, based on military service, education, and patriotism. “If we cannot succeed with the authorities here,” he said, “we will go to a higher power. We will go to President Lincoln, and then we shall know who we are dealing with.”

On March 4, 1864, Jean Baptiste Roudanez and Arnold Bertonneau presented a petition with the names of more than 1,000 prospective Black voters to President Lincoln. (Illustration by Barrington S. Edwards, from THNOC’s forthcoming graphic history Monumental: Oscar Dunn and His Radical Fight in Reconstruction Louisiana)

The meeting’s attendees acted on his words. Dunn and more than 1,000 other Black, property-owning men affixed their names to the petition that would go to President Lincoln. It was a seminal sign of the collaboration between elite Creoles and Americans.

“When Boisdoré gives his speech, he doesn’t say that suffrage should only be for a certain class of people. He’s advocating for all Black people,” said Shaik.

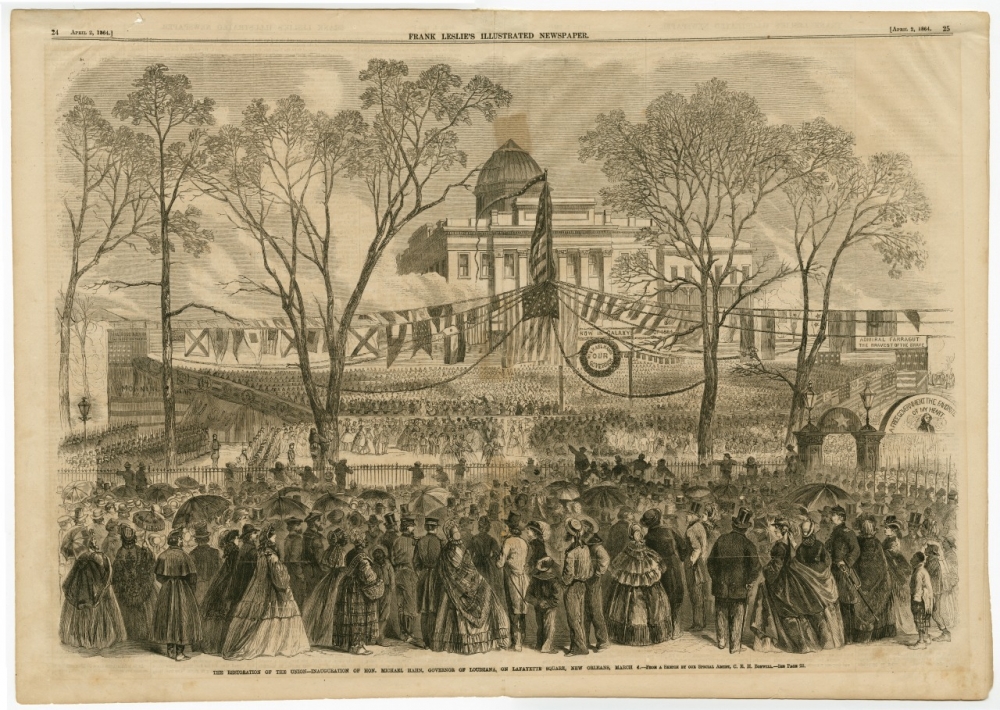

Between that November meeting and the delivery of the petition to Lincoln in 1864, Louisiana re-entered the United States under the president’s 10 Percent Plan, named for the ratio of prewar voters—white voters—who would be required to pledge allegiance to the Union and elect a new government that drafted a new constitution and abolished slavery.

An 1864 illustration from Harper’s Weekly depicts the inauguration of Governor Michael Hahn after Louisiana’s re-entry into the United States. (THNOC, gift of Mr. Harold Schilke and Mr. Boyd Cruise, 1953.35)

To the dismay of Dunn, Boisdoré, and Boguille, the white voters who swore loyalty to the United States and were thus able to participate in the election still did not favor extending that same right to Black people. The Black activists who had been meeting in Economy Hall resolved to move forward on their promise to petition the president, and make the dangerous and costly journey to Washington, DC, in the midst of the war. The group decided to send two educated, successful Creole men who, they hoped, stood the best chance of appealing to Lincoln.

News from Washington

Impressed, but not entirely swayed by the petition and its spokesmen, Lincoln wrote to newly elected Governor Michael Hahn and suggested he consider a limited extension of suffrage to “some of the colored people . . . for instance, the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks.” The new state legislature ignored the issue.

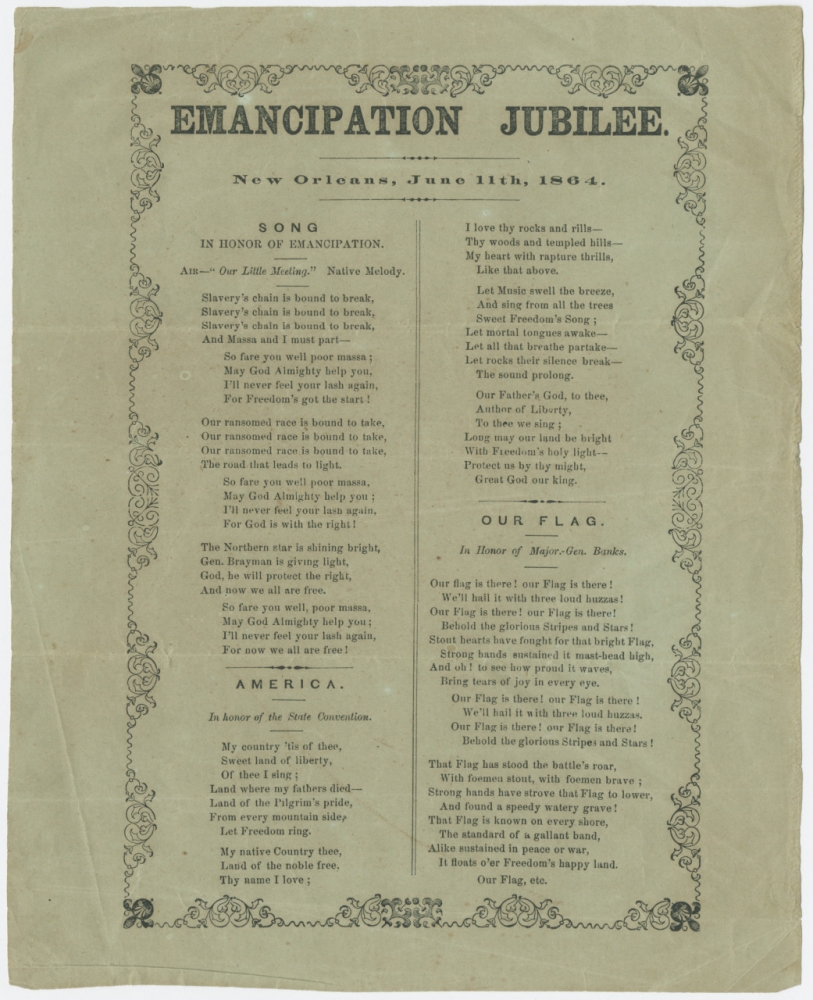

They did, however, craft a new constitution that formally outlawed slavery, which inspired Ludger Boguille to organize a jubilee in Congo Square in the summer of 1864. Creole veterans of the Battle of New Orleans stood alongside newly freed men as the crowd of thousands sang patriotic songs and paraded the American flag in a brass band–led march through the city. The Economy Society and other benevolent associations participated in the procession.

A broadside for the Emancipation Jubilee, which Bougille organized, contained lyrics for patriotic songs and antislavery verse to be performed at the celebration. (THNOC, 91-720-RL)

With thousands of recently enslaved men and women free throughout Louisiana, Dunn’s activism—and business acumen—afforded him a niche in negotiating labor contracts for freedmen, where he developed a reputation for setting workers’ pay well above government-established minimum wages. He received a cut of each contract, building wealth and deepening connections in both the Creole and American communities.

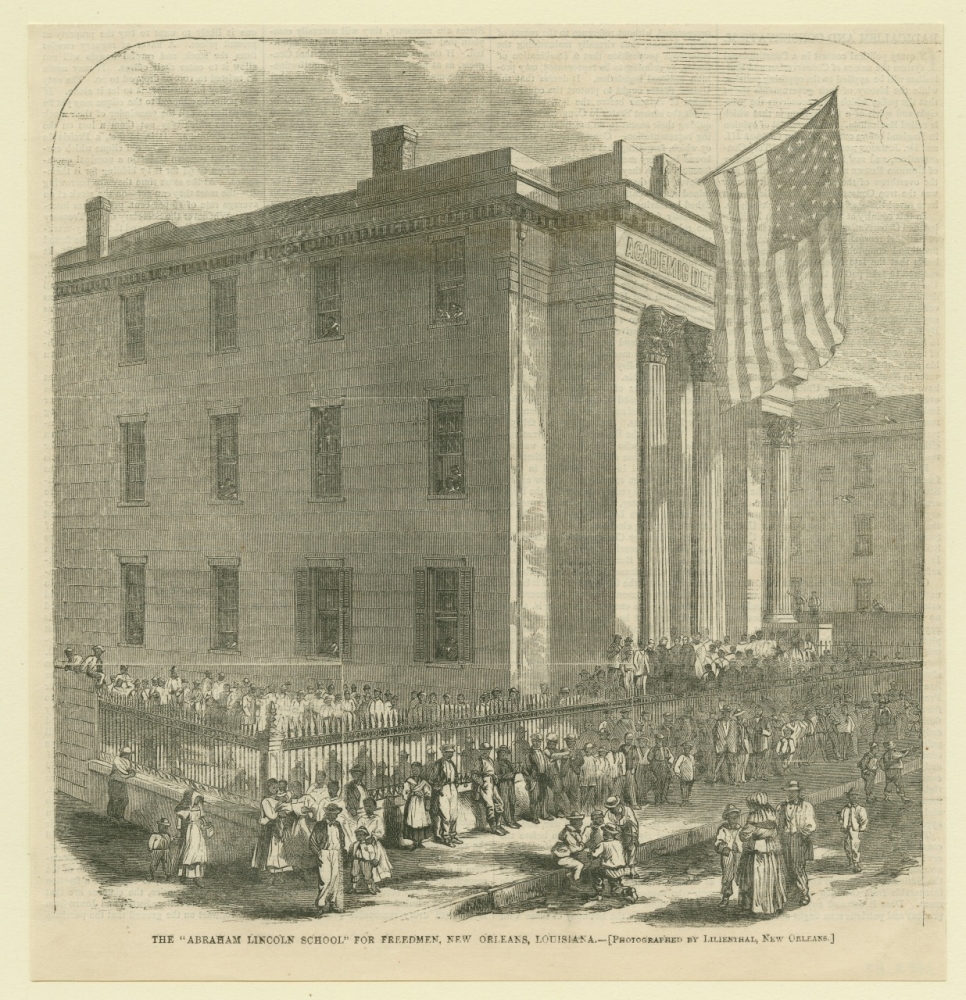

Likewise, Boguille involved himself heavily in the well-being of freedmen. His wife, Mary Ann, ran a freedmen’s school, and some Economy Society members took up posts in the newly established Freedmen’s Bureau to aid fellow Black citizens who had been enslaved before and during the war.

The Abraham Lincoln School for Freedmen is depicted in Harper’s Weekly in 1866. (THNOC, Gift of Harold Schilke and Boyd Cruise, 1953.82)

Continuing the Fight

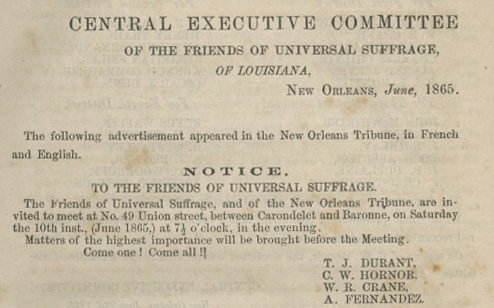

In 1864 L’Union folded, owing in part to death threats and financial woes. In July of the same year, its successor, the New Orleans Tribune, became the nation’s first Black daily paper and was published in French and English. An 1865 edition carried an ad for a meeting of the Friends of Universal Suffrage, an organization made up primarily of white Radicals who envisioned equal civil rights for Black people.

The published proceedings from the convention of the Republican Party of Louisiana, held on Union Street in the American Sector in 1865, reference the advertisement in the New Orleans Tribune. (THNOC, 76-1451-RL)

Dunn attended the meeting, which took place on Union Street in the city’s American Sector. He signed on as a member of the executive committee and would go on to organize a voting drive for prospective Black voters, through Masonic halls and churches, paid for out of his own pocket. Across Canal Street, meetings of the Friends of Universal Suffrage also took place at Economy Hall, and its members continued to advocate for equal rights based on the principles of the US Constitution.

In March 1865, control of Louisiana swung again, and James Madison Wells, a lukewarm proponent of the Union, became governor. President Lincoln was shot and killed a month later.

Wells took a conciliatory approach to ex-Confederates, and statewide elections installed some Democrats—very recently fierce defenders of slavery—into the state legislature. The government promptly went about reinstating laws known as Black Codes, which had limited Black peoples’ rights before the war, an early sign that Confederates, while defeated on the battlefield, could return to control in the South.

In the bilingual pages of the Tribune, the editorial board noted that the Union’s victory could soon be lost: “The idea of social reform is opposed and set at naught by the governing class of the Southern States. The results of the war are opposed and every progress prevented by the resistance and ill will of that governing class.”

Dunn attended his first meeting of the Friends of Universal Suffrage in June 1865. There, he joined the group’s Central Executive Committee. (Illustration by Barrington S. Edwards, from THNOC’s forthcoming graphic history Monumental: Oscar Dunn and His Radical Fight in Reconstruction Louisiana)

In a meeting at Economy Hall in September 1865, the radical Friends of Universal Suffrage—which consisted of Creoles from the Economy Society and Americans, including Dunn—joined forces with the moderate National Union Republican Club—led by white Illinois native Henry Clay Warmoth—to form the Republican Party of Louisiana. The party selected Warmoth as their territorial delegate to take the case for Black male suffrage to Washington, DC.

As the nation emerged from war, this uneasy partnership between activists and moderates would hold long enough for Black men to win suffrage in Louisiana. But as the fight for progress on civil and political rights continued into the Reconstruction era, fractured alliances and bloodshed returned; as one war ended, another began.

Explore Black activism in New Orleans through our Symposium 2021 website.