Willie V. Piazza, known as “The Countess,” was a successful Storyville madam who reigned relatively serenely over her mansion at 317 N. Basin Street. Hers was one of several so-called octoroon houses in the district which featured light-skinned women of color for white clients seeking to indulge in sex across the color line. This desire was rooted in the fantasy of the antebellum planter aristocracy, when sexual power over light-complexioned black women was considered a status symbol.

Historian Alecia P. Long’s research in The Great Southern Babylon: Sex, Race, and Respectability in New Orleans, 1865–1920 (LSU Press, 2005), reveals that Piazza was born around 1865 in southwestern Mississippi, the daughter of an African American woman named Celia Caldwell and a white Italian immigrant named Vincent Piazza. They were unmarried and by the 1880s and were living in separate cities in the state. Willie Piazza, taking her father’s surname, established herself in New Orleans in the 1890s, remaining there until she died at the age of 67 in 1932 at her home, the former brothel on Basin Street.

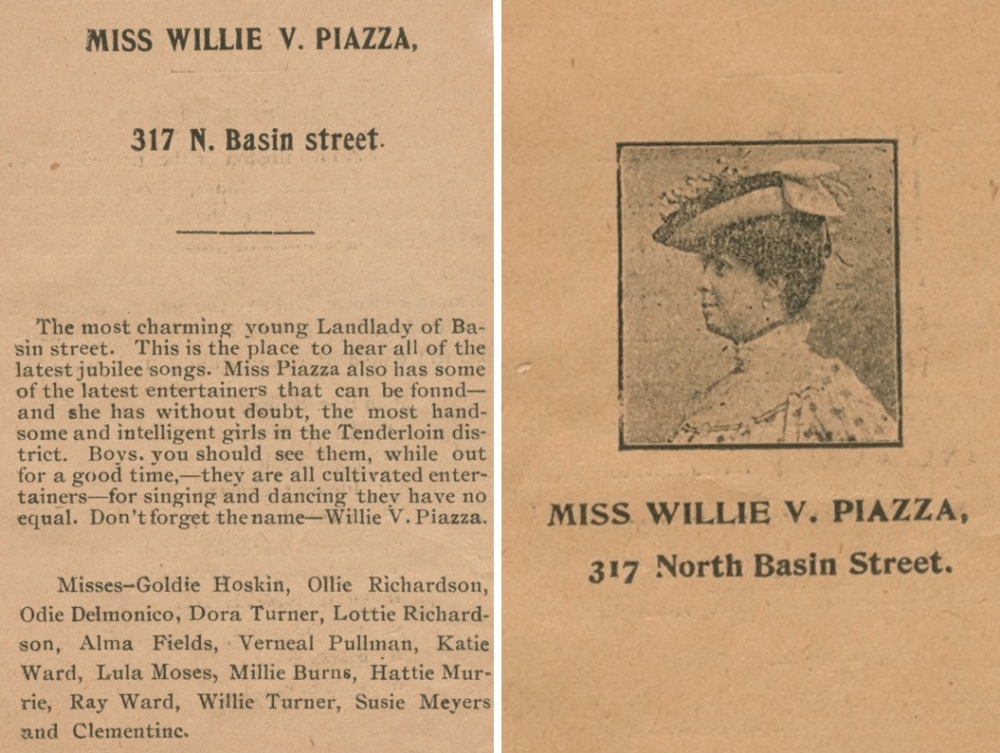

A 1902 Storyville guide contains an advertisement for Willie Piazza's brothel on Basin Street, along with a photo of the famous madam. (THNOC, 1969.19.3)

While little has been substantiated about her life, Piazza cuts a striking figure in local lore. The literature about her depicts a regal woman who lived up to her nickname: sophisticated, intelligent, elegant, and always fashionably dressed, she sported a monocle, smoked Russian cigarettes held in a diamond-studded ivory-and-gold holder, wore a diamond choker, and spoke four languages fluently. One apocryphal story claims that when she and the prostitutes in her employ attended opening day at the Fair Grounds racetrack, New Orleans society ladies often brought their dressmakers along to study their outfits. Also apocryphal is the claim that after the district closed in 1917, Piazza married a French nobleman and became a wealthy matron on the Riviera.

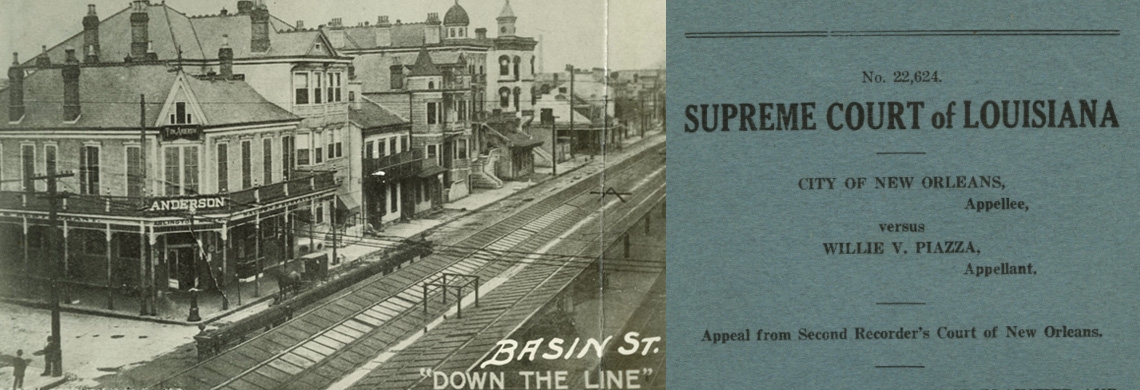

The famous "Down the Line" photograph shows Basin Street, which housed the most luxirious brothels in Storyville. (THNOC, Gift of Mr. Albert Louis Lieutaud, 1957.101)

The famous "Down the Line" photograph shows Basin Street, which housed the most luxirious brothels in Storyville. (THNOC, Gift of Mr. Albert Louis Lieutaud, 1957.101)

Piazza maintained cordial relationships with most of the other madams and was remembered for her generosity toward colleagues in trouble. She was protective of the women she employed in her brothel. She also had an ear for music, employing piano greats Tony Jackson and Jelly Roll Morton, who said she was one of the only madams to keep her parlor piano properly tuned. Unlike many other madams of her era, Piazza managed her money wisely, owned her own brothel, successfully speculated in real estate, and accumulated wealth that kept her comfortable in the years after the district closed.

Piazza’s legacy grew further when she took a stand against racial segregation in the waning months of the district’s legal existence. Storyville was already in a state of decline, under continual attack by a new generation of progressives, reformers, moralists, and a rising middle class seeking to eradicate—rather than merely control—prostitution. After a deadly 1913 shootout prompted a ban on live music in Storyville’s clubs, many of the musicians who had enjoyed steady work and good tips left New Orleans in search of other markets, taking much of the district’s entertainment appeal with them. As Jim Crow segregation cemented a black-white racial binary under the law, sex across the color line—once gently tolerated, under certain conditions—inflamed discussion about the business of Storyville.

The original 1897 ordinance that legalized the red-light district included a provision designating a separate vice area for the use of African American men, near present-day City Hall and Duncan Plaza. This smaller district, now referred to by scholars as Black Storyville, was ignored by white Storyville’s promoters and featured none of the sort of upscale brothels found below Canal Street.

Ordinance 4118, proposed in early 1917 by Commissioner of Public Safety Harold Newman, decreed that Storyville would be entirely racially segregated and that all women “of the colored or negro race” working there, regardless of wealth or standing, would have to move to Black Storyville by March 1. This was New Orleans’s first ordinance specifically intended to segregate residential areas on the basis of race.

A postcard shows a birdseye view of Storyville looking toward Lake Pontchartrain with Basin Street cutting through the center of the image. (THNOC, 1979.362.16)

A postcard shows a birdseye view of Storyville looking toward Lake Pontchartrain with Basin Street cutting through the center of the image. (THNOC, 1979.362.16)

Piazza was disturbed by the prospect of being forced from her Basin Street property, which had been a considerable investment. Accustomed to passing for white when she desired, at first she denied that she was “colored,” but shortly after she legally admitted her race and challenged the ordinance in court.

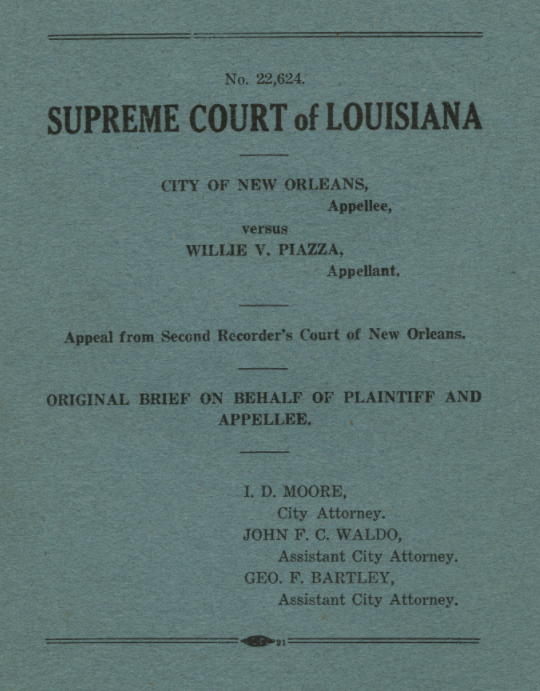

Her lawyer, Nathan H. Feitel, focused on her character, arguing that she ran an orderly house of a type superior to the dives in the area she was being forced to move to, and that her boarders, although prostitutes, were not “common criminals.” Inspired by Piazza, several prominent madams of color—including rival madam Lulu White and, eventually, nearly 20 others—joined her case or filed their own suits against the City of New Orleans to retain their properties and their right to rent to anyone in the red-light district regardless of color.

When the city denied Piazza’s suit, she immediately appealed to the Louisiana Supreme Court, in City of New Orleans v. Willie V. Piazza (1917). The court ruled in her favor, finding that Ordinance 4118 overstepped the original intent of the 1897 act regulating where prostitutes could live. The Countess and her ladies stayed put. The city attorneys’ requests for a rehearing was tabled, and in a few months the issue became moot, when Storyville was forced to close under pressure from the federal government and the military as the United States entered World War I.

Although little-known today, Piazza’s victory was a landmark decision in the decades-long fight against the injustices of Jim Crow and racial segregation. While her immediate intent was self-serving, her resources and sheer perseverance resulted in one of the few instances of the day in which an African American woman challenged the establishment and won.

This is the fourth story in First Draft's series on women's history in New Orleans, in commemoration of the centennial of the 19th Amendement. For more on Storyville, visit THNOC's virtual exhibition Storyville: Madams and Music, co-curated by Pamela D. Arceneaux, and read Arceneaux's deep dive into the district's guides in Guidebooks to Sin: The Blue Books of Storyville, New Orleans, published by THNOC in 2017.

More stories on women in New Orleans history:

The New Orleans woman who fought the longest court battle in US history

What role did Louisianans play in the women's suffrage movement?