This 18th-century tool is an ancestor of the waffle iron, but it tells a much wider story—of religion, foodways, and female enterprise. It is a communion wafer iron, used by the Ursuline nuns in the French Quarter to produce hosts—or sacramental bread—for Catholic Mass.

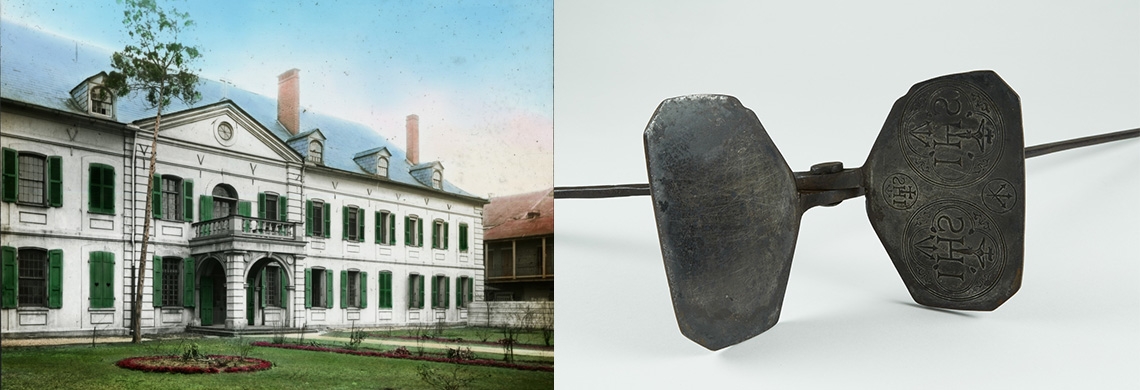

The Ursuline nuns used this wrought-iron tool to press sacramental wafers for Catholic masses in New Orleans's earliest days. (THNOC, 2016.0466.2.1)

The Ursuline nuns used this wrought-iron tool to press sacramental wafers for Catholic masses in New Orleans's earliest days. (THNOC, 2016.0466.2.1)

The use of wafer irons or presses stretches back thousands of years to flat obelios cakes made between iron plates in ancient Greece, a technique the Romans adopted and spread throughout their empire. Beginning in the 13th century, medieval European laypeople baked similar wafers from flour and water or milk, sometimes called oublies, as celebratory tokens or parting gifts for dinner guests, often in observance of feast days. Privately owned wafer irons imprinted these treats with both sacred and secular designs. An iron with a family coat of arms, for instance, could make a perfect wedding gift. As early as the 18th century, European immigrants brought this festive open-hearth baking tradition with them to America.

The original Ursuline Convent is shown here in the late 19th century. The sisters came to New Orleans in 1727, and this building was completed in 1734, making it the oldest extant building in the city. (THNOC, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Elvert M. Cormack, 1981.290.35)

Among those immigrants was a group of Ursuline nuns who came to the young city of New Orleans in 1727. These young women distinguished themselves in the small settlement populated by soldiers, outcasts, enslaved laborers, and a few wealthy landowners. Their mandate was twofold, one assigned by colony officials and another of their own making. The Company of the Indies, which oversaw governance of the colony, tasked the sisters—five of them, per their contract—with providing medical care to the sick. But the sisters had a mission of their own: education for the young women of the colony. As Sister Marie Madeleine Hachard wrote in 1728, “The devil has a great empire here. . . .Not only do debauchery, bad faith, and all the other vices reign here more than in any other place, but they do so in abundance.”

Education was the Ursuline order’s innovative strategy to help sanctify society. In a break from the traditional convent model, the Ursulines opened their doors to young women, in the hopes that graduates would go on to lead devout families as wives and mothers. Boarding daughters of well-heeled French settlers was a source of income, and daytime catechism classes for indigenous girls and both free and enslaved African young women provided another opportunity to foster female spirituality and literacy.

A close-up view shows the iron's inscriptions that include general Christian imagery and details specific to the Catholic church's Jesuit order. (THNOC, 2016.0466.2.1)

A close-up view shows the iron's inscriptions that include general Christian imagery and details specific to the Catholic church's Jesuit order. (THNOC, 2016.0466.2.1)

This particular wafer iron has its own symbolism that devout Catholics can readily interpret. Besides the crucifixes and crosses, clusters of three nails are reminders of Jesus’s suffering and death. The IHS monogram is a general Christian symbol. Its letters are Latin transliterations of the first three letters of “Jesus” in Greek, but the use of the nails and a crucifix rising above the “H” are hallmarks of the Jesuit order. This insignia is fitting, as Jesuit priest Father Nicolas Ignace de Beaubois accompanied the sisters on their voyage to Louisiana and helped them settle in New Orleans.

Large hosts, like the ones made from this iron, would have been used during the Elevation, the point in a Catholic mass when the priest holds the newly consecrated host above his head for all to see. (THNOC, gift of the Green Project, Inc., 2001.63.161)

Smaller wafers, or hosts, from this mold would have been consumed by the lay faithful, while the larger, more elaborate imprints were for the priest’s use. The large host plays an important, dramatic role in the Mass, most crucially at the Elevation, when the priest holds the newly consecrated host above his head for all to see. Catholics believe that the wafer has just been transformed into the literal body and blood of Christ. Seeing the Eucharist held aloft offers a moment for concentrated worship and prayer.

That kind of Eucharistic adoration, along with the spiritual example of the Virgin Mary, was a key element of the Ursulines’ spirituality and educational curriculum. Sister Hachard’s writing mentions that even on their ocean voyage, “Very often we had the blessing of fortifying ourselves with the body of Christ.” One of the nuns’ first orders of business after landing was commissioning a tabernacle to reserve consecrated hosts for adoration at other times. This wafer press created not just decorative objects but also cherished spiritual nourishment.

To celebrate the opening of their new convent in 1734, the Ursulines staged an elaborate parade through the French Quarter. This was a Eucharistic procession (a circa 1920 example of which is shown, right) led by a priest displaying a consecrated communion wafer in a monstrance (like the one shown, left). (THNOC, 1979.325.2500; THNOC, gift of the Green Project, Inc., 2001.63.41)

The epitome of the 18th-century Ursulines’ Eucharistic devotion occurred in 1734, when they staged an elaborate procession across the French Quarter to their newly completed—after seven years and scores of political haggles—convent building. Their religious parade included a priest displaying a large host in a monstrance, girls in white dresses carrying palms, women with candles, and even a young pupil costumed as the order's namesake St. Ursula. The nuns’ first years in New Orleans had seen many setbacks and challenges, including the death of several Sisters from disease, but this was a moment of triumph and thanksgiving. Holy Communion helped the pioneering Ursulines find the strength to build a spiritual enclave in a fledgling new city.

This is the second story in First Draft's six-month series on women in New Orleans history, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. Read the first story on the Louisiana women who fought for the right to vote.