José Francisco Xavier de Salazar y Mendoza was the most significant artist in New Orleans during the Spanish colonial period. He was born on the Yucatán peninsula in the 1750s. Very little is known about his early life and training in Mexico. After moving to New Orleans with his family in 1782, he became a well-known portrait painter. His paintings, which feature prominent New Orleanians, provide a visual record of the city’s upper class in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In them, we can see what the most influential members of New Orleans society wore, how they styled themselves, and, by looking at props and poses, some of the things they valued. But Salazar’s portraits are more than a who’s who of Spanish New Orleans. Taking a closer look, we can see interesting connections between those prominent citizens and their legacies.

Célèstia Antonia Lavillebuevre, Who’s Connected to a Ghastly Tale

Salazar’s portrait of Lavillebuevre (THNOC, gift of Olga and Yvonne Tremoulet, 2005.0345.2)

The woman playing the piano in this Salazar portrait is Célèstia Antonia LaVillebuevre. She was the mother of Edmond Forstall, president of the New Orleans Sugar Refinery in the 1830s. Another of her sons, Francis Placide Forstall, was married to Marie-Borja Delphine Lopez, eldest daughter of Marie Delphine Macarty, more commonly known as Madame Lalaurie.

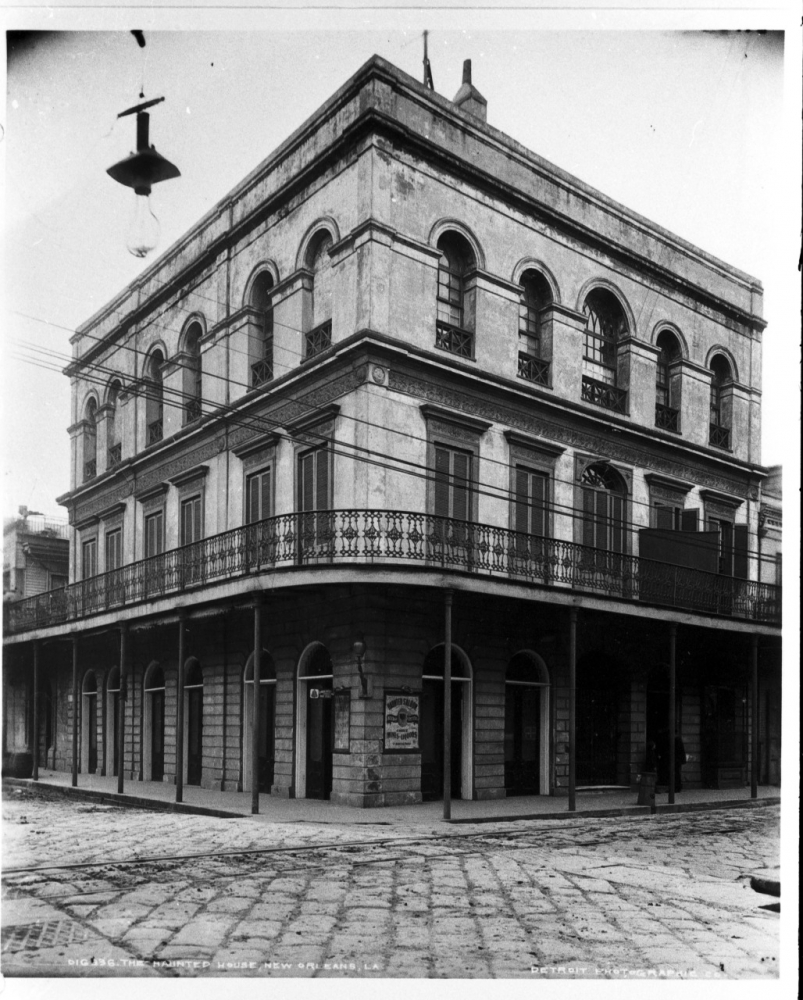

Madame Lalaurie was a wealthy, well-connected socialite who owned a house on the corner of Royal and Governor Nicholls streets. On April 10, 1834, a fire broke out in the kitchen. Rescuers and fire marshals discovered the cook chained to the stove and multiple enslaved people tortured and mutilated in the uppermost room. Following the gruesome discovery, a mob of local bystanders ransacked the mansion, leaving it in a ruined state for four years. It underwent numerous changes as a conservatory of music, a bar, and an apartment building. Architectural changes to the building included the third-floor addition later in the late 19th century, and a second floor added to the rear building in the 1970s.

Lalaurie fled New Orleans, eventually settling in Paris. Little is known about her later years or death. In 1924 a copper nameplate bearing her name was found near the Forstall family tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1.

The Lalaurie mansion as it appeared in the mid-20th century (THNOC, 1974.25.3.118)

Lalaurie’s legacy lives on in folklore and popular culture. New Orleanian novelist George Washington Cable included a dramatic retelling of Lalaurie’s story in his 1890 book Strange True Stories of Louisiana. The 20th century saw the publication of multiple embellished versions of the tale, often with grim and lurid details that did not appear in contemporaneous accounts. Jeanne deLavigne’s 1946 book Ghost Stories of New Orleans, for example, claims that one victim’s mutilations and amputations left her “looking like a human caterpillar” and that another’s broken and reset limbs made her look like “a human crab.” More recently, Kathy Bates won an Emmy for her portrayal of a fictionalized Lalaurie in the New Orleans–set third season of American Horror Story.

Martin Duralde, Who Started a Fashion Line (Sort Of)

Salazar’s portrait of Duralde (courtesy of Dr. and Mrs. Martin Duralde Claiborne III)

Martin Duralde was the commander of the Opelousas Post during the late Spanish colonial period. He was keenly interested in the natural world and used geologic evidence and Native American oral histories to compare contemporary and historical landscapes and vegetation. Still, he is not well remembered for his civil service or his scholarly pursuits. Instead, he is best known for his connection to a famous Louisiana family, the Claibornes.

Duralde was the father-in-law of the first US American governor of Louisiana, William C. C. Claiborne. The Virginia-born Claiborne was a descendant of one of colonial Virginia’s most influential political figures and a member of a well-established political family. His brother Ferdinand, who owned a plantation in Pointe Coupée Parish, Louisiana, was the great-great-grandfather of Lindy Boggs, the first woman from Louisiana elected to Congress. Claiborne Pell, namesake of the Pell Grant, can also trace his roots to the Claibornes.

Duralde’s daughter Clarisse and William C. C. Claiborne had one son, William Charles Cole Claiborne Jr. Through that line, Martin Duralde is the great-great-grandfather of fashion designer Liz Claiborne.

Don Andrés Almonester y Rojas, Whose Legacy Shaped the French Quarter

Salazar’s portrait of Almonester (courtesy of the Office of Archives and Records, Archdiocese of New Orleans)

Spanish noble Don Andrés Almonester y Rojas (1724–1798) immigrated to Louisiana in 1769. As a colonial official, he used his power and contacts with the Spanish crown to amass a fortune in real estate and land transfers. He financed the rebuilding of the city following the fires of 1788 and 1794, especially the St. Louis Cathedral, where he was buried in 1798.

In 1787 Almonester married Louise de La Ronde (1758–1825). Louise was also connected to local real estate and development. Her father, chief engineer and architect Ignace François Broutin, designed the Old Ursuline Convent, the oldest surviving building from the French Colonial period in New Orleans. Broutin’s stepson was Antoine Philippe de Marigny, whose grandson Bernard later subdivided his plantation and developed the Faubourg Marigny.

Almonester and Louise had only one surviving child: Micaëla Almonester, who would become the Baroness de Pontalba upon her marriage to her maternal cousin, Joseph-Xavier Célestin Delfau de Pontalba. The union was not a happy one; Micaëla’s father-in-law tried to kill her to gain control of her financial assets before shooting himself, and Micaëla separated from her husband. Like her father, the baroness was involved in real estate development. Between 1849–1851, she constructed the Pontalba Buildings that still flank both sides of Jackson Square. The development not only revitalized the area surrounding the Place d’Armes but also helped popularize cast iron as an architectural feature. Thanks to the buildings—and to her dramatic marital woes—she is perhaps even more famous than her father.

The Lower Pontalba as it appeared at the turn of the 20th century (THNOC, 92-48-L.331.1789)

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.