Jackson Square, or the Place d’Armes, as it was originally known, began to take its shape in August 1721, when French engineers laid out a plan for the new colonial capital of La Louisiane.

They conceived a fortified town at the bend on the Mississippi River that Bienville had selected in 1718 with the assistance of local Native Americans who had long known the site as one end of a portage between river, bayou, and lake. At the time, it was little more than a cleared patch of canebrake and a scattering of crude huts. The new town would embody the latest engineering principles, including a grid of streets surrounding a central square fronting the river. This was to be the main public gathering place.

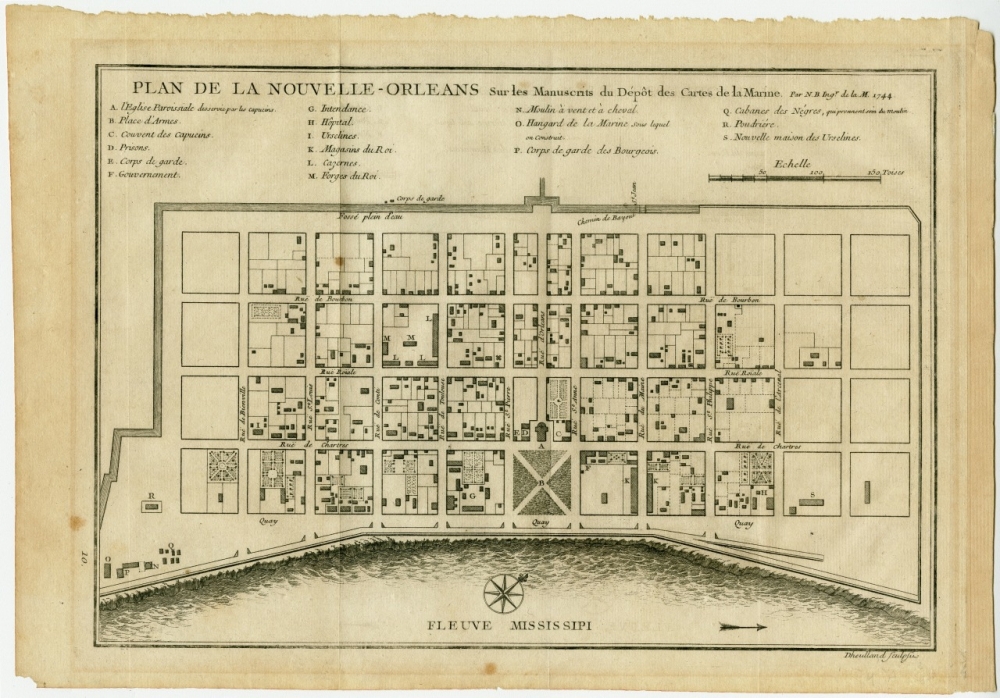

This 1744 plan of New Orleans shows the Place d’Armes as an open square along the river with an “X” through it. In its earliest days, the square was intended to be a mustering, or gathering, place for soldiers and was flanked by barracks. (THNOC, gift of Mr. Patrick Henley, 2011.0377)

A place d’armes was considered in early 18th-century French colonial architecture to be a key feature of any good town plan. In his treatise on the elements of fortification, engineer and architect M. Le Blond observed that “a large and spacious place d’armes is … more agreeable than a small one. It is an ornament for the town. Moreover, the principal buildings, like the great church, the town hall, the Government House or the house of the Governor ordinarily have their principal doorway on the place d’armes. All this attracts there a large concourse of people; it ought to have enough space to be adequate for all that, without difficulty.”

As the square’s name suggests, it was a mustering place for men of arms, and indeed, two L-shaped barracks were erected on either side of the square to house colonial soldiers and their officers.

As a place of civil, military, and religious authority, the Place d’Armes was where the colonial French inhabitants of Louisiana could gather for strength and reassurance. One can imagine people congregating there after church, or on occasions when new ships arrived in port with news and supplies from Europe or elsewhere in the colonies. Holidays brought crowds to the square, as did the occasions when authorities carried out public punishments or executions. Throughout this early period, the Place d’Armes was a wide-open, grassy space, probably quite muddy much of the time from horse hooves plowing up the turf.

Two women are pictured visiting Jackson Square in 1898. (THNOC, 2006.0150.83)

The proudest users of the Place d’Armes were probably the soldiers. Militia officers and men would muster there periodically to drill in basic formations and procedures, or to present themselves in formation to the governor for his inspection. Events of international importance took place in or near the Place d’Armes, including ceremonies related to the transfer of the Louisiana colony from France to Spain in the 1760s and then back to France in 1803.

The purchase of Louisiana by the United States was formalized when officials signed documents in the Cabildo. According to Pierre Laussat, the colonial prefect sent by Napoleon Bonaparte, “lovely ladies and city dandies graced all the balconies on the Place d’Armes… At none of the preceding ceremonies had there been such a throng of curious spectators. We the commissioners then moved to the main balcony of the city hall. As we appeared, the French colors were lowered and the American flag raised.”

Another event of international significance occurred when New Orleans came under the threat of invasion by British troops in the waning days of the War of 1812. Andrew Jackson—a firebrand of a major general from Tennessee—met and reviewed local troops and volunteers in the Place d’Armes in mid-December 1814. There Jackson addressed and inspired various companies of volunteers, including two battalions of free men of color, to work together to defend their common home. Within days, they were fighting veteran British troops in a series of battles that culminated in one of the greatest upsets in military history.

This 1830s hand-colored engraving shows the Place d’Armes, as viewed from the Mississippi River, more than 100 years after it was originally laid out. (THNOC, the L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1940.4)

In the years that followed, new people flocked to New Orleans by the thousands, and the city expanded to accommodate them. As it grew, other public squares came into use, including Lafayette Square in the upriver Faubourg St. Mary (now the Central Business District, or CBD), the Place Publique of the Tremé subdivision—also known as Congo Square—and Washington Square in the downriver Marigny neighborhood. Each had its own constituency, whether Anglo-American, French or Spanish Creoles, or free people of color.

Even so, the old Place d’Armes remained the true center of the city, and it continued to serve as the site of important ceremonies, military parades, and welcomes for visiting dignitaries. A triumphal arch, designed by city surveyor Joseph Pilié, was built in the square for General Lafayette’s visit to the city in 1825.

And yet, while architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe described the Place d’Armes in 1819 as “infinitely superior to anything in our Atlantic Cities as a water view of the city,” the square had become a bit run down and neglected. Within weeks of his arrival, the celebrated Latrobe—who had worked on the US Capitol building in Washington—made a plan for enclosing the square with decorative wrought iron railings and gates with grand arches, along with a fountain.

Celebrated architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe drew up this plan for grand gates to the square, but his design was rejected by the city council. Latrobe’s plan for a central spire at St. Louis Cathedral, however, did go forward. (THNOC, acquisition made possible by Krista and Mike Dumas, 2021.0049)

The city council rejected these improvements, implementing a less costly design by Pilié that included a fence and central fountain. Pilié’s plan was never completely realized, but city records indicate that ten dump carts were hired to haul filling dirt into the Place d’Armes, and a number of sycamore trees were planted along either side.

In the late 1840s, the Baroness Micaëla Almonester Pontalba, visiting the city to check her local real estate holdings, saw the Place d’Armes as a muddy, neglected parade ground. She personally paid for extensive landscaping improvements to the square. She also designed and constructed two Parisian-style row house buildings on either side of the square at a cost of over $300,000 (they’re worth rather more than that now).

An image taken in 1850 or 1851 shows ongoing landscaping work in the square with the central spire of St. Louis Cathedral not yet enclosed. Also pictured are the new French-styled mansard roofs and cupolas at the Cabildo and Presbytère and one of the Baroness de Pontalba’s two rowhouses peeking out of the right-hand side of the image. (©Pontalba Family, courtesy of the Baron de Pontalba)

These major upgrades to the square and the surrounding architecture persuaded the wardens of the St. Louis Cathedral that they had better improve its scale and grandeur. The city council also decided to upgrade the Cabildo and Presbytère on either side of the cathedral with French-style mansard roofs and cupolas.

In January 1851 the recently renovated Place d’Armes was officially renamed Jackson Square, in honor of the general who had saved the city from British invasion, and a committee began raising funds for an appropriate monument in the square. While the square’s new name seemed to bestow the greatest honor on one man, this had also been the place where the local parts of Jackson’s army had stepped forward and volunteered to fight. Further, it was a place where all men, regardless of race, creed, or nationality, had been accepted as defenders of a shared country.

A newspaper illustration depicts a crowd at the inauguration of the Andrew Jackson statue on February 9, 1856. However, several of the details of the drawing are innacurate, such as St. Louis Cathedral, which is shown as it would have appeared in the 1840s, rather than with the new facade and towers dating from 1850 and after. The Pontalba buildings, built in the late 1840s, are also left out. (THNOC, bequest of Boyd Cruise and Harold Schilke, 1989.79.16.4)

Sculptor Clark Mills of Charleston received the commission from committees in Washington and New Orleans to create a suitable monument. Mills’s first Jackson statue was erected in Washington DC in 1853. This was the first equestrian statue created by an American, and the first anywhere that featured a horse standing unsupported on its rear legs. Mill’s second statue—commissioned for Jackson Square in New Orleans—was unveiled for the public in February 1856. The monument’s inauguration reportedly drew 10,000 onlookers to the square.

Though New Orleans has grown far beyond its colonial boundaries, Jackson Square remained the true heart of our city, even after James Gallier’s new City Hall next to Lafayette Square was completed in 1850. Important visiting dignitaries have continued to visit and make speeches in or adjacent to the old square, which has also hosted generations of musicians and artists and many millions of tourists from all over the world. Jackson Square was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1960 and was recognized in 2012 as one of our country’s great public spaces by the American Planning Association.

Photographer Michael A. Smith snapped this image of Jackson Square during French Quarter Fest in 1985. (THNOC, ©Michael A. Smith, 1986.125.257)

Yet for all of the people and history that have passed through it, the square still occupies the same modest two-and-a-half acre area that French engineers laid out three centuries ago.