Today, one can spend virtually every moment with a soundtrack of recorded music. In addition to personal music libraries, consumers have access to algorithm-fed playlists to match every conceivable mood, location, time of day, or activity. On social media platforms like TikTok, users can collaborate across the world to remix favorite songs. Many people even rely on recorded sounds to sleep, using white noise apps to blanket the unconscious.

In this 21st-century valley of aural plentitude, it can be jarring to survey the landscape of musical life before the advent of home stereos, CDs, and Spotify. Until the invention of the phonograph, live music was the primary means of listening to music. Balls, operas, and other public entertainments were wholeheartedly embraced in New Orleans, but equally important was music made and enjoyed in the home. The theme of this August’s 2023 New Orleans Antiques Forum is “Music to My Eyes: Material Culture of Southern Sound,” and the first day will focus on the domestic register, from parlor music and soirées musicales to player pianos, music boxes, and the early “talking machines.” Subsequent days will explore antiques and ephemera related to performance, such as a lecture on country-and-western costumes, and the material culture of New Orleans music, from Congo Square to jazz landmarks. A preconference activity will offer participants a private show-and-tell of THNOC’s music-related holdings, as well as a private tour of the New Orleans Jazz Museum at the Old US Mint.

This photograph, by C. Milo Williams, shows a New Orleans family gathered ’round the piano in 1895. (THNOC, 1974.25.25.8)

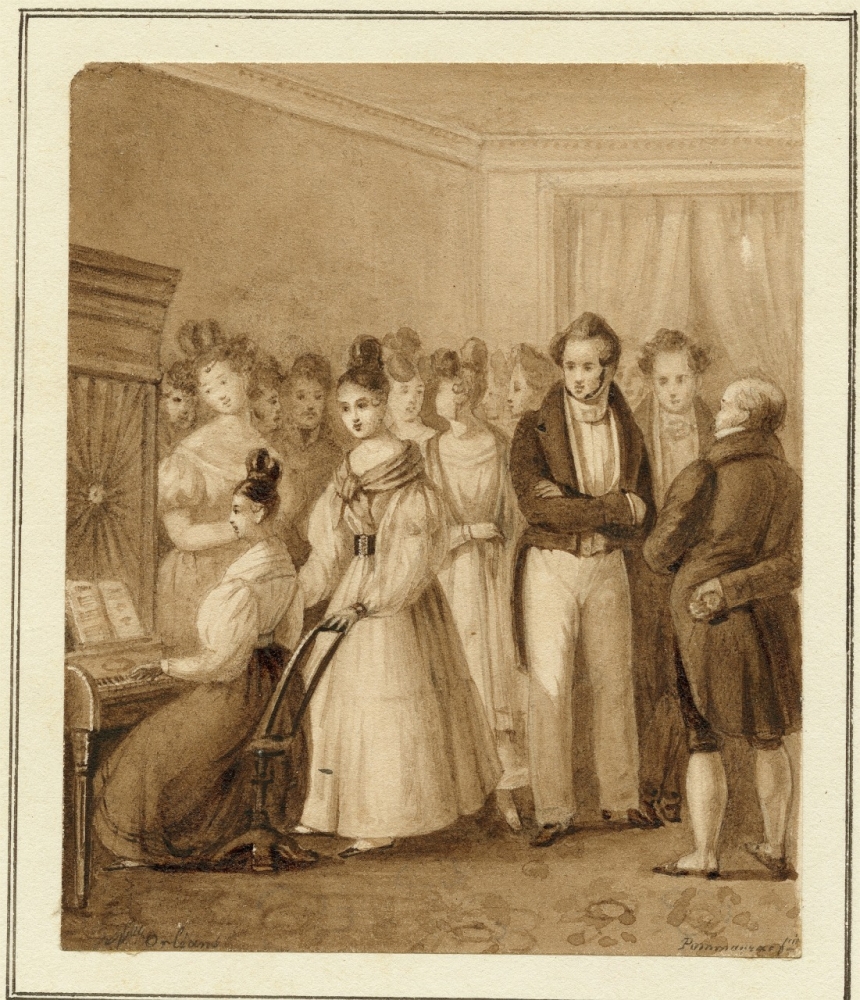

Throughout the 19th century, homemade music transcended class, but for middle- and upper-class women it provided a particularly pronounced structure and purpose to their days. For middle-class women, as well as men, proficiency in music was a path to economic security—as music teachers. For upper-class young women, playing an instrument was an important cultivation, making them more “accomplished” and therefore more salable on the marriage market.

The most common way to display one’s musical accomplishments was through parlor music, explains Dr. Candace Bailey, who teaches musicology as the Neville Distinguished Professor at North Carolina Central University. “It’s the age of visiting—calling cards and calling hours—and so some people would take their music with them, so when they’d drop in, they would say, ‘Would you like to hear what I’ve been working up?’ Or, maybe you’re hosting, and you’d want to play the piano while other people danced the latest dance.”

Parlor music was a cultural anchor for middle- and upper-class society in the 19th century, allowing young women to show off their talents while providing a soundtrack to social occasions. (THNOC, 1962.1.8.3)

In 19th-century New Orleans, “French pieces, French opera, French everything” was the most popular, Bailey says. Because of the free time available to young women of the leisure class, “the level of musical expertise that women achieved was much higher than we give them credit for. Particularly for wealthy women, because they had more time for practice and lessons, they were playing the same pieces as the professionals.”

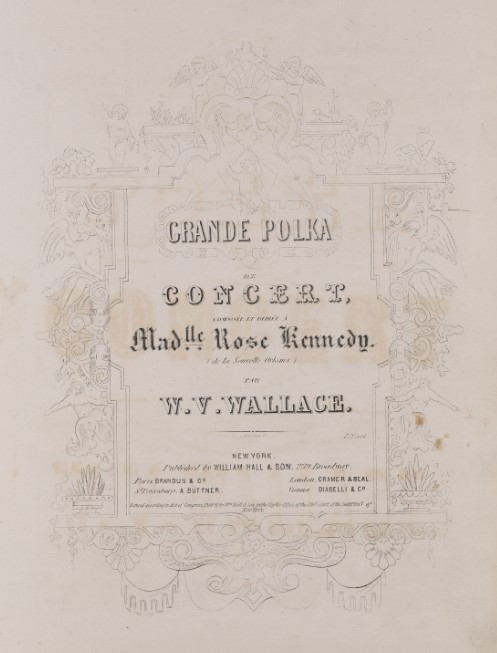

For people who were accomplished enough, another opportunity to showcase their skills was the salon or soirée musicale, private concerts typically hosted by society doyennes at their residences. There, a talented hobbyist could perform alongside a visiting professional. In New Orleans, it was common for professional musicians and composers to share patron-muse relationships with society ladies, Bailey says. Rose Kennedy, for example, the daughter of a US Mint executive (not to be confused with the mother of John F. Kennedy), wowed Louis Moreau Gottschalk with her playing of his famed Bamboula. Two different composers dedicated pieces to her, including the Irish composer William Vincent Wallace, who attached her name to his Grande polka de concert.

The dedication to New Orleans socialite Rose Kennedy is featured prominently on the cover of William Vincent Wallace’s Grande polka de concert, published in 1850, when Kennedy was just 16 years old. (THNOC, 86-1180-RL)

Wealthy people with large parlors or dedicated music rooms could afford grand pianos, but for many households, compact square pianos were the answer. They ranged in size and scope—the number of keys depended on how much one could pay—and could be modest Shaker designs or feature gilding, inlay, or hand-painted ornamentation. From the early days of the American republic through much of the 19th century, “Americans love the square piano,” says NOAF speaker Alexandra Cade, an adjunct curator at the Sigal Music Museum in Greenville, South Carolina. “They’re more affordable, so more people can buy them. . . . Until the late 19th century, there were more square pianos produced in the United States than there were grands.”

This square piano was made by Alpheus Babcock in Philadelphia in the 1830s. (Courtesy of the National Museum of American History)

What supplanted the square piano in the late 19th century was the upright piano. And for many consumers, that upright was a player piano. Automatic instruments and musical machines had existed for centuries, going back to the musical clocks that came out of central Europe in the 16th century and spread to town squares and church steeples across the continent. “The technology became a consumer good with the industrial revolution, in the early 19th century—with the ability to miniaturize the mechanisms,” explains Robert “Bobby” Skinner, a New Orleans musician and restoration specialist of automatic instruments. “The Swiss were geniuses at manufacturing these. They evolved out of cuckoo clocks, and then they put them in music boxes, watches, mechanical birds—just ridiculously small pieces.”

The innovations in technology also spawned automatic instruments of enormous size. “Some of them played small orchestras—a small bass drum, a snare drum, a woodblock, triangle, castanet, a small set of organ pipes,” Skinner says. “All of this stuff was wrapped in a luxurious, extremely elaborate case. . . . In a residence, this would have been the focal point of a music room.”

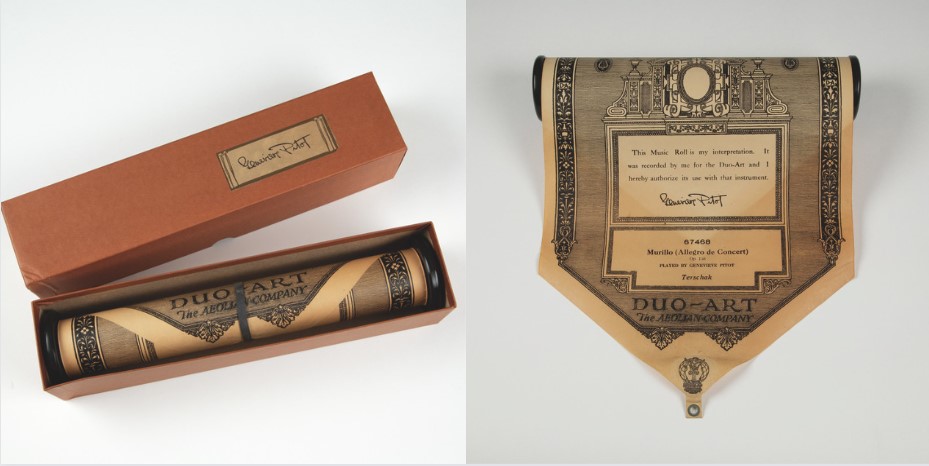

Player pianos, which debuted in the 1890s, offered a twofer to consumers: a playable instrument as well as an automated one. Later models known as reproducing pianos brought a then-unparalleled level of fidelity and nuance to the music being recreated. The perforations on the paper rolls inserted into the piano captured the original performer’s dynamics, expression (lightness or heaviness of touch), pedal phrasing, and tempo changes. For the ultra-wealthy, there were reproducing pipe organs, such as the original, 703-pipe Aeolian on view in THNOC’s Seignouret-Brulatour House. Composers such as Sergei Prokofiev, Jelly Roll Morton, Eubie Blake, and George Gershwin all recorded piano rolls.

Piano rolls and organ rolls work the same way, via perforations on the paper that reproduce the performance of the original player. This organ roll, Murillo: Allegro de concert, by Adolf Terschak, can be played on THNOC’s fully restored Aeolian organ in the Seignouret-Brulatour Building at 520 Royal Street. (THNOC, gift of an anonymous donor, 2017.0344.1)

In New Orleans, D. H. Holmes department store and Werlein’s music store were the main suppliers of both player pianos and piano rolls, which people amassed by the hundreds. “It was typical for you to get a subscription to receive rolls—a dozen or so every month—upon purchase of a piano,” says Skinner, who himself is in possession of “thousands” of rolls collected by his grandmother.

Around the same time that player pianos were flooding department stores, phonographs began to enter the market. In the 1870s Thomas Edison had invented a sound recording device that operated from a cylinder with tiny pegs, similar to the mechanism in a music box, but it was bulky. Moreover, Edison did not see the full potential of recording technology. “He had a failure of imagination,” says music historian John McCusker, who will speak at the forum about the introduction of the phonograph. “You don’t have to explain to the public why you need a lightbulb. You never have to explain why you need a telegraph. He misses the crucial importance of sound recording: it’s not the invention, it’s the content.”

This music box, manufactured in Leipzing, Germany by Polyphon Musikwerke circa 1895, is an example of a music technology that was popular just before the invention of the phonograph.

Two men who did see that potential were Emile Berliner and Eldridge Johnson. Berliner, a German inventor who emigrated to the United States as a young man, had been experimenting with sound recording using a flat-disc process. In 1894 he introduced the Berliner Gramophone, which played records via a hand-cranked motor. Berliner’s technology caught the attention of Johnson, an engineer and manufacturer of bookbinding machines. Upon learning of the Gramophone, Johnson developed a spring-driven motor to play the discs, and in 1901 he founded the Victor Talking Machine Company. “Flat records easily bury cylinders in the market because flat records are easier to produce,” McCusker explains. “You can work from a master, usually ‘wax,’ or metallic soap. . . . From that you craft a metal stamper impression, and that stamper you stamp into the shellac that you use to make records.” The 78 rpm record was born.

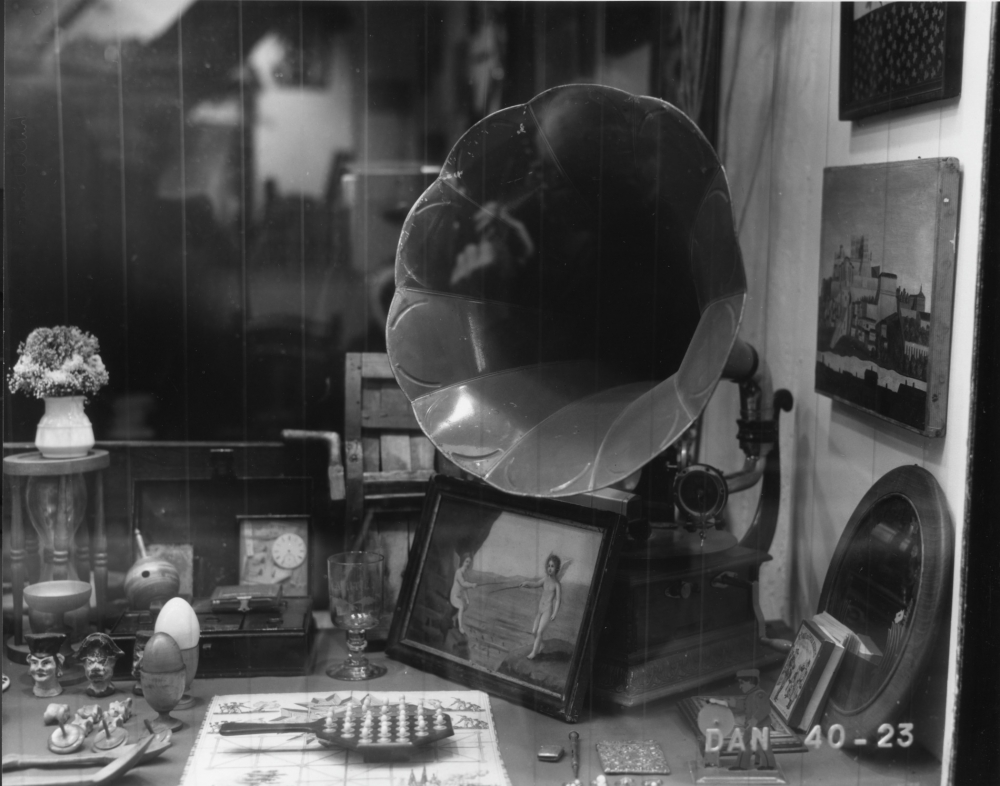

Clarence John Laughlin titled this image The Phantom Gramophone. (The Clarence John Laughlin Archive at THNOC, 1983.47.4.9364)

“Between 1910 and 1920, that is the equivalent . . . of the ’80s when everybody got a VCR,” says McCusker. “Everybody got a phonograph in that decade.” One important factor was the introduction of the Victrola, a Victor-model phonograph that offered users a more attractive, compact cabinet, as well as greater control over the volume. Previously, the only way to change the volume of a phonograph was to get a larger or smaller “horn,” the acoustic amplifier used to emit sound. Another development was the first hit record, “Crazy Blues,” recorded by Mamie Smith in 1920. “It’s the first number-one record with a bullet, as they say,” McCusker says. “It sells hundreds of thousands.”

The recording industry was off and running. Over the 1920s, radios became common home furnishings, and the broadcast era began. “Radio killed off the player piano,” Skinner says.

“This is the first time that a house that wasn’t musical, that didn’t have musical instruments or people who play them, could be a musical house,” McCusker says. “I don’t think there’s any way to overstate how important that was.”

Banner image: THNOC, 1999.39

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.