It’s been more than two decades since Cash Money Records took over for the nine-nine and the two thousand, but on any given weekend in New Orleans, someone somewhere is playing “Back That Azz Up.” The second single from Juvenile’s 400 Degreez, “Back That Azz Up”—and the radio-friendly edit “Back That Thang Up”—opens with strings. Within the first few notes, people rush from their benches and barstools, end conversations mid-sentence, give up their spots in bathroom lines, and congregate on dance floors to bend it over and buss it open.

Juvenile, Mannie Fresh, and dancers from the “Back That Thang Up” music video. (Courtesy of UMG on behalf of Cash Money)

A century and a half earlier in Paris, another New Orleanian debuted a song with a distinctive, ear-catching opening. Louis Moreau Gottschalk’s Bamboula begins with a set of four dyads—octaves, played fortissimo at the bottom of the keyboard, so that the left hand pounds on the piano as if it were a drum. The Parisian elite might not have been as uninhibited as contemporary clubbers, but it’s probably safe to bet that whatever the 1840s opera house version of what New Orleanians call catching a wall was, when they heard the opening to Bamboula, they did it.

Listeners would be forgiven for thinking that a strong, percussive intro is the only similarity between the songs, but “Back That Azz Up” and Bamboula share another important feature that shaped the music and the songs’ legacies: they’re both from New Orleans, and they both brought distinctively New Orleans sounds to a global audience.

Juvenile in 1998, the year “Back That Azz Up” was recorded (THNOC, 2018.0491); Gottschalk around 1842, the year he left to study in France (THNOC, 2019.0145)

Piano virtuoso and Bamboula composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829–1869) was the son of a London-born Jewish merchant and a white Creole mother. The New Orleans of his youth was a fast-growing city with a bustling port and the country’s largest market for the sale of enslaved people. Longtime Anglophone residents and English-speaking newcomers from the United States mingled with German and Irish immigrants, free people of color, and enslaved Black people from Louisiana and beyond. There was also a large population of French-speaking Creoles and refugees from Saint-Domingue, including Gottschalk’s own grandmother. Wealthy Creoles like the Gottschalks flocked to opera houses and salons, and Gottschalk, who started playing piano around age 5, was recognized as a prodigy. He was only 11 when he gave his first concert at the St. Charles Hotel, and he travelled to Paris to study two years later.

Arguably, the creators of “Back That Azz Up” were also young prodigies. Mannie Fresh (b. 1969) was the son of DJ Sabu (1942–2018), one of the earliest pioneers of the New Orleans rap style known as bounce. As a child, Fresh worked at his dad’s shows. By the 1980s, he was DJing at local clubs and making a name for himself through his innovative use of 808 drum machines and other equipment that was still rare in bounce music. Juvenile (b. 1975) was still a teenager when he was featured on DJ Jimi’s song “Bounce for the Juvenile,” and was just shy of 20 when he released his debut album on the New York label Warlock.

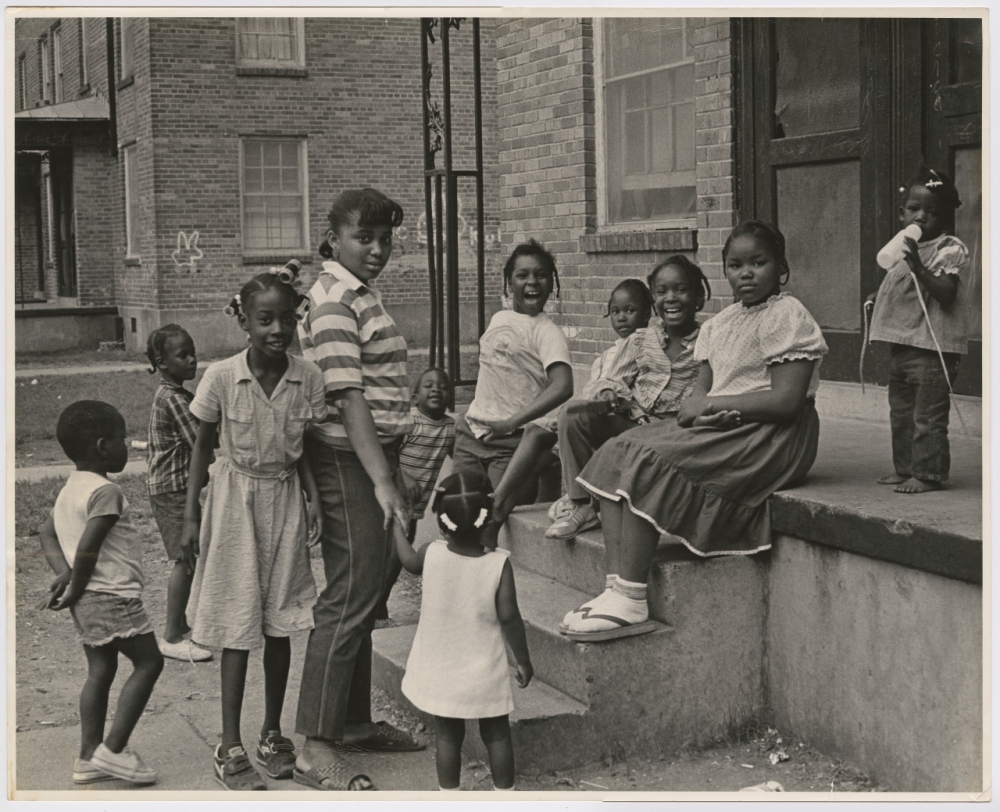

Kids in the Magnolia Projects, where Juvenile grew up (THNOC, 2016.0172.4)

Though they grew up more than a century apart, Gottschalk, Mannie Fresh, and Juvenile all spent their early years in an exceptionally musical city. In addition to the opera houses he visited with his family, Gottschalk, in his era, would have seen public minstrel shows and heard songs based on European folk music in taverns and on the streets. Growing up just a few blocks from Congo Square, he heard the music from enslaved and free Black people’s weekly Sunday gatherings there, where drumming and dancing went on for hours. Young Gottschalk also got a healthy dose of Black music at home through his nurse, an enslaved Saint-Domingue–born woman named Sally.

19th-century Creoles at the opera as depicted by illustrator Alfred R. Waud in 1866 (THNOC, gift of Mr. Harold Shilke and Mr. Boyd Cruise, 1953.57.1)

All those sounds laid the sonic foundation for what would become jazz, funk, and hip-hop, so that 150 years after Gottschalk’s time, the same New Orleans music he heard would also influence Mannie Fresh and Juvenile. Like Gottschalk, Juvie and Fresh all incorporated the music they grew up hearing—and the place it came from—into their most famous songs.

Bamboula is one of Gottschalk’s four Louisiana Creole pieces. While it’s named for a deep-voiced West African drum and various dances associated with it, it is actually a fantasia—a piece of music unrestrained by the rules of stricter musical forms like waltzes or mazurkas—based on the music of the composer’s childhood. Gottschalk composed Bamboula not in Louisiana but in the French countryside, where he had come down with typhoid fever. During his febrile delirium, he began to wave his hands. His doctor and family assumed this was part of his illness. It was only after he began to get better that, according to his sister’s account, “he one day got up and wrote out Bamboula, which he said had been running in his brain during the illness.”

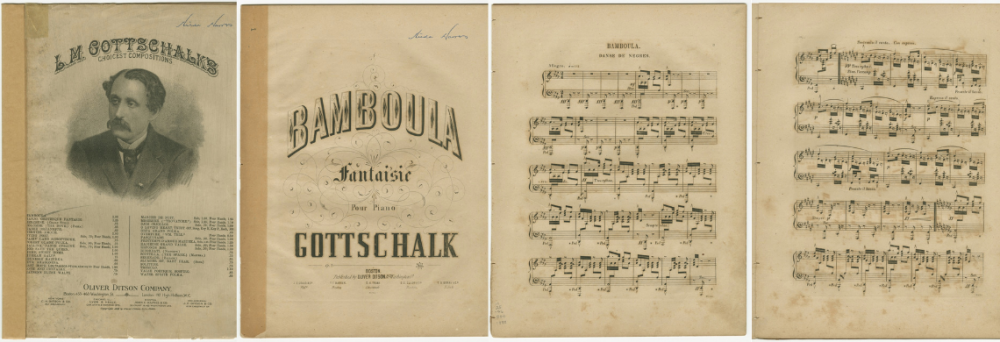

Sheet music for Louis Moreau Gottschalk’s opus Bamboula (THNOC, 86-913-RL)

The song in Gottschalk’s feverish mind was a Creole melody, “Quan’ patate la cuite”—one of the songs Sally had sung to him, about hot sweet potatoes—and it forms the melodic backbone of Bamboula. He shifts the short tune into different keys, uses dramatic changes in dynamics and articulation, and adds a sentimental, minor-key middle section to contrast with the bombastic main theme. Arpeggios and thick chords add layers and variety to the “Quan’ patate” motif, and the propulsive energy of the Afro-Caribbean bamboula rhythm undergirds the composition.

Mannie Fresh’s use of samples in “Back That Azz Up” is not unlike Gottschalk’s use of “Quan’ patate la cuite.” Like Gottschalk, Fresh chose melodies that were well known in his hometown. One was the 1980s song “Triggerman,” by the Showboys. (In a move that was common in bounce music production at the time, Fresh didn’t use the actual “Triggerman” song; instead, he made his own clip that was very close to it.) The iconic strings that open the song and drop in and out through its end are also rooted in New Orleans: as Fresh said in a 2019 interview for the 20th anniversary of “Back That Azz Up,” the sound is reminiscent of UGK’s string-heavy mid-’90s tracks, which were in turn inspired by the Meters. Fresh builds texture by layering the strings with snares and even his own voice. The song’s main vocal tracks add another layer of local flavor: Juvie raps the chorus and main verses, while Mannie and then-newcomer Lil Wayne take guest verses, and it’s easy to hear how their New Orleans accents shape the rhymes and cadence of vocals.

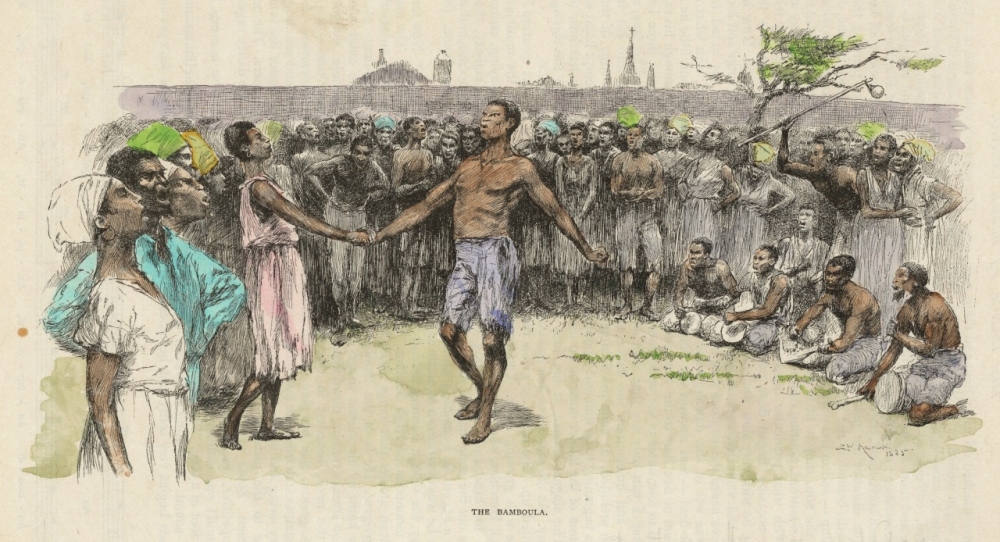

Gottschalk’s naming the song Bamboula was a shrewd branding choice. Rather than use the song’s original quaint title, Gottschalk gave his opus a name that his white American and European audiences would find exotic and titillating. The song’s subtitle, Danse de nègres, would have further connected the piece to an eroticized imagining of Blackness and Black bodies in contemporary white audience members’ minds. Leon Escudier’s 1848 review is evidence of the associations Gottschalk’s audience connected to the word “Bamboula.” “Who does not know the ‘Bamboula’? Who is there who has not read the description of that picturesque, exciting dance which gives expression to the feeling of the negroes?” Gottschalk’s genius, writes Escudier, allows listeners to experience the exotic dance without having “lived under the burning sky from whence the Creole draws his melodies” or being “impregnated with these eccentric chants.”

An 1886 magazine illustration depicts what the bamboula dance might have looked like at Congo Square. The onset of the Civil War put a stop to the gatherings. (THNOC, 1974.25.23.54)

“Back That Azz Up,” an expertly crafted dance hit, also conjures images of Black bodies dancing. That was no accident. For Mannie Fresh’s verse, Juvenile gave the producer free rein over the lyrics, so long as they were raunchy; Fresh obliged. Created by Black artists with a Black audience in mind, the song’s sexualization of Black bodies is far less racially problematic than that of Bamboula. Instead of standing outside of the song, like Gottschalk and his audience, Juvenile centers himself—and the women he admires—in the song. His vocals create a kind of call and response. He calls the azzes to back up, and, in response, they do.

Bamboula and “Back That Azz Up” share another important similarity: as rooted as they are in New Orleans, both transcended regional fame enough to become hits. Both songs helped catapult their creators to national—and international—stardom, and have helped inspire musicians outside of the city. Gottschalk is widely seen as integral to the birth of jazz and ragtime. “Back that Azz Up” has been sampled by everyone from City Girls to Beyonce. Drake even reimagined it as a mournful ballad with his song “Practice.” In 2021, Juvenile and Mannie Fresh joined forces again and, with the help of New Orleans rapper Mia X, reworked the hit as “Vax That Thang Up” to promote COVID vaccinations—evidence of the song’s lasting legacy. It’s proof that, no matter how much time passes, New Orleans music continues to drop it like it’s hot.