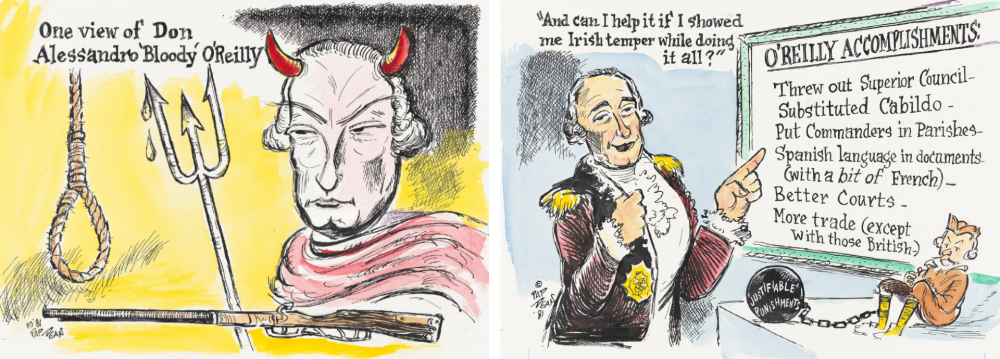

Alejandro O’Reilly, Louisiana’s second Spanish governor, has long been maligned for his part in bringing to justice those who authored the 1768 insurrection against Spanish rule in the colony. Due to the arrest, trial, and execution of five of the leaders of that coup, he was saddled with the moniker “Bloody O’Reilly,” which has persisted to this day. Throughout the 19th century, many historians overlooked that he was sent to Louisiana not only to firmly establish the Spanish crown’s authority over the colony but also to institute orderly Spanish rule, which he accomplished through a number of administrative, military, diplomatic, and economic improvements. Not until the 20th century did historians use primary sources and archival documents to present a more demonstrable historical perspective of the man and his tenure. Alejandro O’Reilly was not the bloody enforcer of Spanish rule over Louisiana that some have made him out to be but rather a fair judge and competent administrator.

France’s claim to the Louisiana territory dated to 1682, when La Salle descended the Mississippi River and declared its entire basin to be property of the French king. Eighty years later, France ceded its Louisiana territory to Spain via the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau of 1762. The colony’s influential white Creole merchants and planters were not at all happy that they had become subjects of the Spanish crown, so they worked to solidify their positions and their incomes. Because the first Spanish governor, Antonio de Ulloa, did not arrive until 1766, they had ample time to exercise their influence over the Superior Council, which was the colony’s only government at the time. Rather than express allegiance to a new master, they were intent on maintaining the autonomy they had enjoyed owing to France’s neglect of the colony during the Seven Years’ War.

This video is the first in a four-part series inspired by THNOC's slate of in-gallery talks for the exhibition Spanish New Orleans and the Caribbean / La Nueva Orleans y el Caribe españoles. In addition to “bloody” governors, the talks will focus on massive fires, Enlightenment ideas, and imperial transfers of power. The talks are 20 minutes each, happening at 2:30 p.m. Thursdays and Saturdays, November 3, 2022–January 21, 2023. For more information about the talks and the exhibition, click here.

The established elites’ antagonism toward the new Spanish governor was augmented by Ulloa’s failure to host a celebration in honor of his recent marriage when he arrived in New Orleans with his new bride. For the party-loving Creoles, this lapse in social convention was an affront, regarded as proof that Ulloa considered them to be inferior.

The elites were quick to protest the Spanish trade regulations Ulloa imposed in 1766 and again in 1768. The policy inhibited the lucrative free trade to which the elites were accustomed, limiting Louisiana’s trade to nine ports in Spain and outlawing trade with Great Britain and Mexico. The colony was also required to purchase only Spanish wine, as the importation of French wine was forbidden. The only goods that could be shipped to other countries were those that could not be sold in Spain. From the locals’ point of view the Spanish mercantilist policies were ruinous.

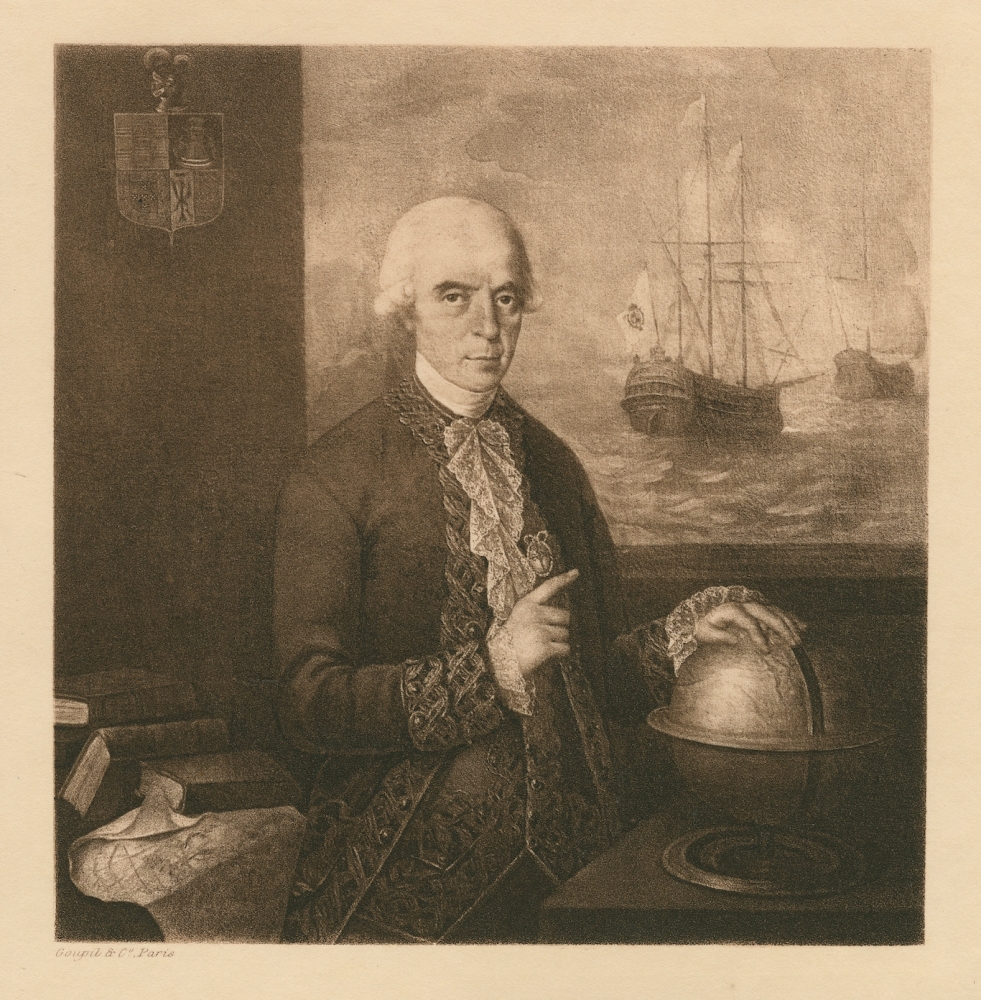

Governor Antonio de Ulloa was a promoter and practicioner of science, contributing to the fields of navigation, astronomy, and mathematics. His bookish personality, however, did not jibe with the socially active ruling class of white Creoles, who took his failure to party sufficiently as a snub. (THNOC, gift of Thomas N. Lennox, 1991.34.12)

These elites decided that an insurrection was in order, and they were prepared to lead it. The ringleaders spread propaganda to persuade the populace that Ulloa was a tyrant and that the Spanish government would make slaves of them all. The ringleaders also incited the Germans and Acadians who had settled near the city, having convinced them that Ulloa’s governance was not legitimate. On October 29, 1768, over a thousand armed men assembled in the Place d’Armes in opposition to Ulloa’s administration while the Superior Council met to consider a petition that declared him a usurper possessing illegal authority. The governor boarded the ship Volanté that afternoon and left for Havana on November 1. The insurrection appeared to be a success. The Spanish crown, however, did not give up so easily and soon appointed a new governor.

Alejandro O’Reilly arrived on the scene on August 18, 1769. In keeping with his mandate from Carlos III, he wasted no time bringing to justice those who were accused of crimes against the crown. On August 21 the leaders of the conspiracy were arrested in the king’s name. To calm the fears of those who had fallen victim to the anti-Spanish propaganda promulgated by the insurrectionists, O’Reilly issued a general amnesty to the public.

This sketch, from a Spanish colonial report, is a representation of the troops drawn up in the Place d’Armes (now Jackson Square) on August 18, 1769, to commemorate O’Reilly’s arrival in the city and his disembarkation from the frigate Volante. (THNOC, 97-30-L)

Despite the beliefs of many 19th- and early 20th-century historians who questioned O’Reilly’s fairness—one going so far as to call him an “armed executioner”—the trial of the rebellion leaders was conducted strictly according to Spanish law. It began with detailed depositions from both Spanish and French officials. Each of the accused had his own attorney to represent his interests. After two months of proceedings, the court determined that the conspiracy’s leaders were guilty of sedition and treason, having knowingly acted against the wishes of the kings of both Spain and France.

The five ringleaders were sentenced to death. Those considered accomplices received prison terms, not death. Only those without whom the insurrection would not have occurred were executed.

Once justice was served, O’Reilly focused on the other tasks that Carlos III had assigned him. He set up a government like those found throughout the Spanish Caribbean world. To replace the Superior Council, he installed a cabildo, or city council, whose job was to preserve order, maintain the public welfare, and administer justice. Its members, appointed by O’Reilly as regidores, or aldermen, were all of French extraction.

This editorial cartoon from 1980, by Preston A. Dean, shows the stark difference between O'Reilly's historical reputation versus the reality of his accomplishments as an administrator. (THNOC, the Anna Wynne Watt and Michael D. Wynne Jr. Collection, 2013.0027.5.99)

He then took action to ensure the colony’s security by reorganizing its defenses and improving relations with the Native Americans in the area. The reorganization included a battalion of free men of color in addition to regular and militia forces. To spare the treasury undue expense, he eliminated forts that served little purpose. In order to stabilize the economy, he placed price controls on staple goods, reformed trade practices, and made sure that the government was adequately funded. Considering the welfare of the colonists, the governor pressed for and gained exceptions to the 1766 and 1768 trade regulations that would allow Louisiana to sell timber and other products it produced, and he negotiated a market in Cuba for those products.

Perhaps his most enduring contribution was what many refer to as the Code O’Reilly. It was not a newly written law code but rather a condensed version of a collection of laws that were readily applied, thus establishing Spanish colonial law and creating stability in the colony.

O’Reilly’s goal had been to accomplish his assignment in Louisiana as expeditiously as possible. Spain’s king had chosen him to subdue a rebellion, punish its organizers, and install an orderly government in Louisiana. In just six months he accomplished all three, leaving Louisiana a set of laws and institutions that served the colony well for decades.