Happy Carnival 2022. Whether we choose to gather in person or not, we can still celebrate through and with music. And we will.

Mardi Gras is as much about music as it is about parades, parties, family, and all the other traditional (or non-traditional) memories and realities that the season conjures. For me, Mardi Gras is mostly about music, and my memories around that music.

My love of music is subjective and intensely personal, just like how we each celebrate Mardi Gras. The songs that I share in this playlist are just that—personal. The playlist is not meant to compile the best Carnival classics of all time. In most cases, the songs were not released in a Mardi Gras context at all. I selected each of them to represent my Mardi Gras life as a native New Orleanian.

Having now experienced two (understandable) Mardi Gras cancellations—1979 and 2021—I’m reminded that the music is especially important, because the music can never be canceled; nor the spirit that the music inspires; nor its creators and makers in our city, our home; nor the memories that the music represents. I hope that these selections inspire new memories, celebrations, and good feelings in this new pandemic Mardi Gras world. Mask up, enter at your own risk, and get ready to dance.

This image of Big Chief Bo Dollis of the Wild Magnolias was featured on the cover of the group’s 1990 album I’m Back . . . at Carnival Time! (Photograph by Michael P. Smith © THNOC, 2007.0103.8.1)

This original version of “Handa Wanda” is as influential as it is funky. Credited to Bo Dollis and the Wild Magnolia Mardi Gras Indian Band when it was recorded and released in late 1970, it is the first time that the synergy of traditional Mardi Gras Indian* music and then-contemporary funk music, utilizing electric instruments, was committed to tape.

The recording was inspired by the Wild Magnolias’ appearance earlier that year at the Tulane Jazz Festival (helmed by student Quint Davis, who was fresh off of co-organizing the first New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival that April). The studio session brought together the Wild Magnolias Mardi Gras Indians, on vocals and percussion, with a band featuring pianist and bandleader Willie Tee, bassist George French, and the Meters’ drummer Joseph “Zigaboo” Modeliste. The recording was released as a two-sided 45-rpm single on Davis’s own Crescent City Records, and has rocked jukeboxes (and now playlists) ever since, while singlehandedly creating the genre of Mardi Gras Indian funk.

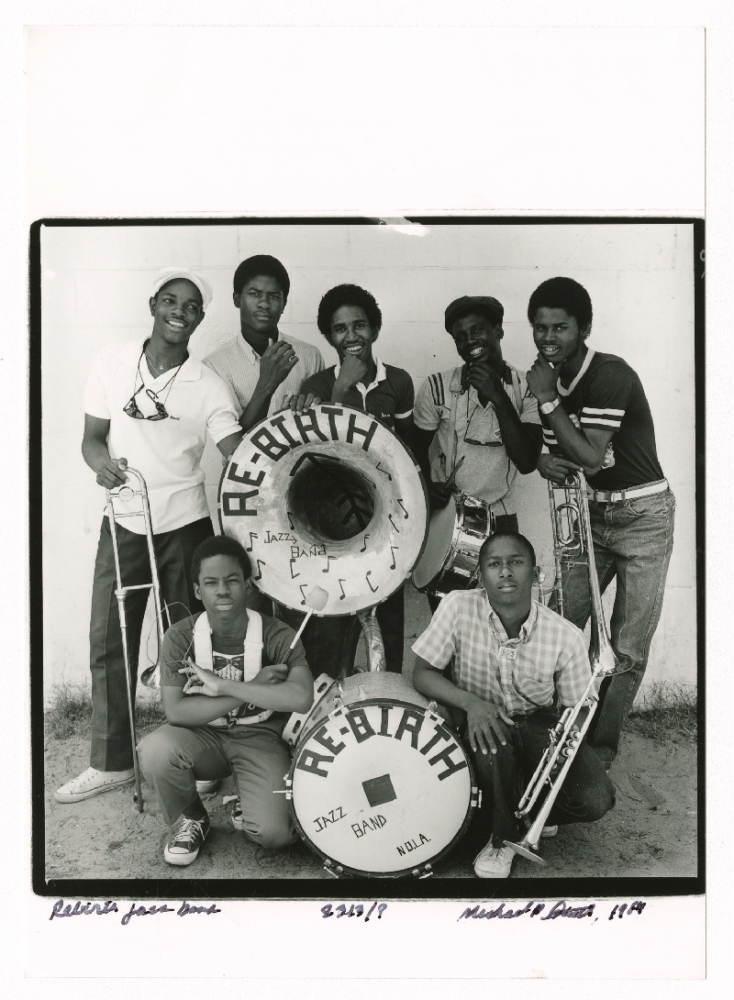

The Rebirth Brass Band formed in 1983, a year before this photo was taken, and pushed the brass band genre forward by incorporating elements of hip-hop into their sound. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith © THNOC, 2007.0103.4.352)

Like the Wild Magnolias incorporating electric funk into their traditional sounds, the Rebirth Brass Band also broke the mold. Their 2001 album Hot Venom stirred controversy as the first New Orleans brass band recording to include a “Parental Advisory: Explicit Content” label. It also boasts some of the group’s hardest-hitting music, including “Thinking About Ya,” one of a few of the album’s non-explicit cuts that I loved dancing to during my days following the band on Tuesday nights at the Maple Leaf Bar uptown and Sunday nights at Joe’s Cozy Corner in the Tremé.

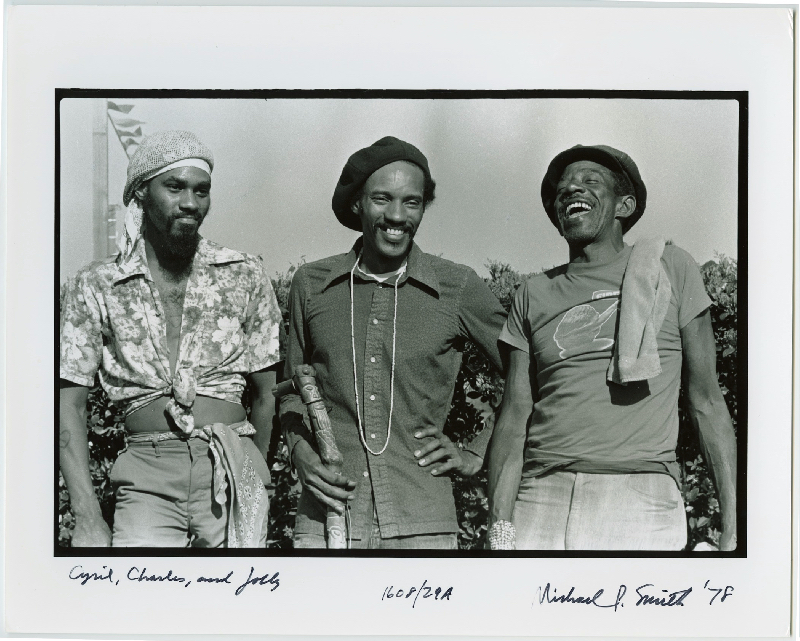

From left: Cyril and Charles Neville, of the Neville Brothers, stand with their uncle, George Landry, a.k.a. Big Chief Jolly of the Wild Tchoupitoulas Mardi Gras Indians, at the 1978 New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith © THNOC, 2007.0103.4.692)

New Orleans is the home of funk, and this playlist features two of its biggest exports in the genre (and two of my favorite bands): the Meters and Chocolate Milk. They also represent the legacy of Allen Toussaint, who produced and worked closely with both groups in the 1970s, as well as my memories of growing up in New Orleans—my dad played their records not just during Mardi Gras, but all year long. He especially loved the Neville Brothers’ music. I’ve honored their legacy here with “Here Dey Come,” which represents their first commercial recording together, as vocalists and percussionists behind the Wild Tchoupitoulas Mardi Gras Indians. Led by their uncle, Big Chief Jolly (George Landry), the Wild Tchoupitoulas’s self-titled album was released in 1976 and featured a rhythm section that included the Meters, as well as production by Allen Toussaint.

Fats Domino sits at a piano in a recording studio in 1957. (THNOC, 1994.94.2.2284)

“Big Chief” and Jessie Hill’s “Ooh Poo Pah Doo” are New Orleans music classics that I grew up hearing around the house, and I attribute those to my mother, who loved the original 1950s rock ’n’ roll and rhythm and blues that came out of the city. She especially loved Fats Domino—I can picture her dancing to his “Let the Four Winds Blow.” I included two beloved versions of “Big Chief”: Professor Longhair’s 1964 original, which features Longhair’s incendiary piano attack alongside vocals, writing, and whistling solo by Earl King, and Dr. John’s 1972 remake. I love both versions, but Dr. John’s represents a simmering kind of funk that you can also hear on a new favorite, “Mardi Gras in New Orleans,” released in 2021 by Big Sam’s Funky Nation (not to be confused with Professor Longhair’s 1949 song of the same name, which was also released as “Go to the Mardi Gras”).

The Hot 8 Brass Band plays during a parade of the Young Men Olympian Junior Benevolent Association in 2013. (THNOC, gift of Charles M. Lovell, 2017.0001.12)

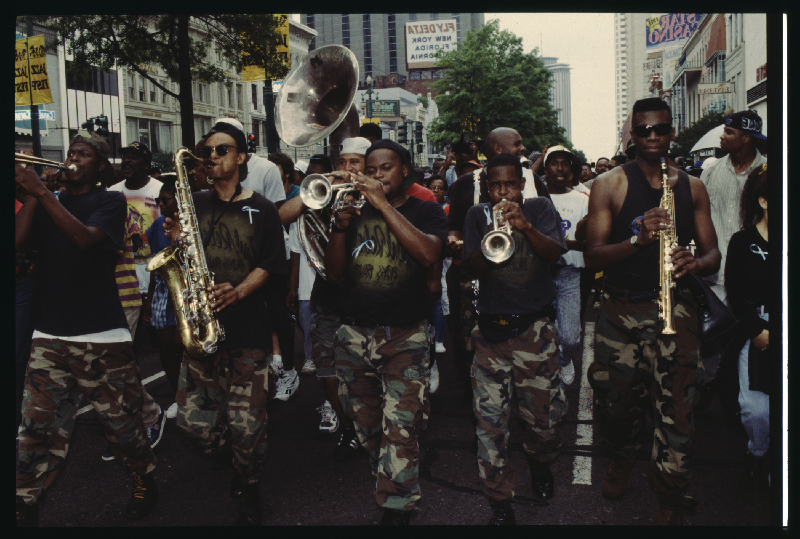

The New Orleans brass band tradition is one that you don’t get anywhere else, and I can’t imagine Mardi Gras without those sounds rolling through the streets. The Hot 8 Brass Band’s “What’s My Name?” is a clever interpolation of both George Clinton’s “Atomic Dog” (1982) and Snoop Dogg’s “Who Am I (What’s My Name)?” (1993). The feeling of the Soul Rebels’ classic “Culture in the Ghetto” is exactly what Mardi Gras represents to my community. And “Who Dat Called Da Police” by James Andrews’s New Birth Brass Band represents Carnival in more ways than one.

The Soul Rebels parade during the 25th anniversary celebration of the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival in 1994. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith © THNOC, 2007.0103.8.2511)

More people need to hear and talk about Indian Blues, a 1992 recording by saxophonist (and Mardi Gras Indian) Donald Harrison Jr. Harrison’s father, Donald Harrison Sr., was Big Chief of the Guardians of the Flame Mardi Gras Indians, and appears throughout Harrison Jr.’s marriage of Mardi Gras Indian culture and swinging contemporary music. Represented here from that album is “Hu-ta-Nay,” with vocal and piano assistance from Dr. John.

Irma Thomas performs at Tipitina’s in 1977. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith © THNOC, 2007.0103.1.638)

The next several minutes of the playlist are pure party: “Get on Up,” my favorite Walter “Wolfman” Washington song; Kermit Ruffins and the Barbecue Swingers’ “Do the Fat Tuesday,” the perfect Mardi Gras anthem; a wonderful live version of “I Done Got Over” by Soul Queen of New Orleans Irma Thomas, which reminds me as much of her Mother’s Day concerts at the Audubon Zoo as it does of my mom dancing at Mardi Gras; “Stop Pause, Do the Jubilee All” by DJ Jubilee, the ultimate dance song for those of us who came up on New Orleans bounce; and “Street Parade” by Earl King, my favorite Mardi Gras song of all time.

Earl King performs at the Gator Ball in 1980. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith © THNOC, 2007.0103.8.459)

“Gentri Fire in the City,” released in 2021 by Flagboy Giz, a Wild Tchoupitoulas Black Masking Indian*, provides a sobering reminder for 2022 that the Mardi Gras celebration will cease if we don’t nurture the people who give the city and its culture its meaning and life.

Rounding out the playlist are “Fire,” perhaps my favorite Rebirth Brass Band song; the traditional Mardi Gras Indian prayer “Indian Red,” as performed by the Wild Tchoupitoulas with the Neville Brothers and the Meters; and the Meters’ “Hey Pocky A-Way,” because you (I) can’t have Mardi Gras without it.

You can’t have Mardi Gras without music, either. Not in 2022, not ever.

*In recent years, “Black Masking Indian” has emerged as a term that some use alongside or instead of “Mardi Gras Indian.” I respect each person’s choice to self-identify, and offer this disclaimer for those whose preference dictates one term over another.

Guest contributor

Photo by Avery White

DJ Soul Sister is an internationally known DJ artist, vinyl collector, and veteran WWOZ-FM show host of her 25-year running Soul Power show, which features 1970s–mid-1980s funk, disco, and soulful rarities from her personal collection of thousands of records. She was the first DJ to receive a prestigious Big Easy Entertainment Award, and has performed with everyone from Questlove to George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic.

Born Melissa A. Weber in New Orleans, she is also a music historian who has presented her research at academic conferences for the International Association for the Study of Popular Music (IASPM) and the National Council for Black Studies, among others. She teaches a History of Urban Music course for the College of Music and Media at Loyola University New Orleans, and serves as curator of the Hogan Archive of New Orleans Music and New Orleans Jazz, a division of Tulane University Special Collections.

Want more curated playlists?

- Take a musical tour of 1950s Bourbon Street

- New Orleans Bracket Bash: Music Madness edition

- THNOC’s New Orleans favorites