By the time she came to New Orleans in 1799, Suzanne Douvillier was a famous dancer on both sides of the Atlantic, but the sensational story of how she got here goes far beyond the stage.

Born in France in 1778 as Suzanne Theodore Vaillande, she became a child prodigy, studying ballet at the Paris Opera and performing at the Comédie Française before moving to the wealthy colony of Saint-Domingue (Haiti), likely with a theater troupe. There she formed a bond with Alexandre Placide, a versatile man of the theater as adept at acrobatics and acting as he was in theater management and choreography.

In August 1791 an uprising of enslaved people against the French administrators plunged Saint-Domingue into revolution, and many of the French residents fled.

A mere month before the Revolution, Placide took Douvillier, then just 13 years old, to the United States, where she was introduced to American audiences as “Madame Placide,” though they were never legally married. The duo performed in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia over the next couple of years, establishing her reputation throughout the U.S. as an exquisitely graceful dancer and emotive performer. In 1794 they settled in South Carolina, to work at the Charleston French Theatre: she as a performer, he as an administrative partner.

Jean Baptiste Fransicqui—himself a refugee of the Haitian Revolution—owned and operated the theater, which also employed a handsome young singer and actor named Louis Douvillier.

By 1796 Douvillier had grown quite amorous of the young “Madame Placide,” who by all accounts was very beautiful. His feelings were so obvious that Alexandre Placide challenged Douvillier to a duel by swords in the streets of Charleston.

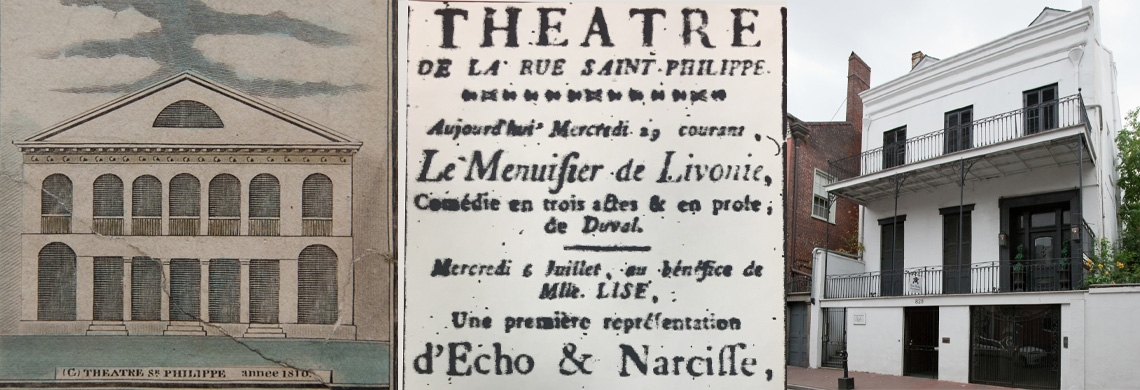

The 700-seat St. Philip Theatre became La Gaité and was one of three performing arts venues in New Orleans during the early 1800s. (The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1946.2 i-xiv)

Suzanne reportedly fainted, and a crowd intervened before either man could strike a mortal blow. Even though Douvillier came out wounded, he won Suzanne’s affections, as they promptly married and left Charleston to perform across the country.

After this considerable scandal, the theater owner Francisqui severed his relationship with Alexandre Placide and also left Charleston. Francisqui toured the U.S. for a few years, occasionally performing with the newlywed Douvilliers, before settling in New Orleans in 1799. The Douvilliers joined him in New Orleans later that year.

At the time of their arrival, New Orleans was a Spanish colony, but its performing arts—what existed of them— were decidedly French. Throughout most of the 18th century, France’s cultural exports to its North American colonies flowed into the more refined Saint-Domingue. The Revolution led many performers, like the Douvilliers and Francisqui, to eventually resettle in New Orleans, and their arrival contributed to what most people believe to be the birth of the performing arts in the Crescent City.

Shortly after Francisqui’s arrival, he founded the New Orleans opera-ballet. He directed the opera troupe, which included the Douvilliers, from 1800 to 1803. They performed at the St. Peter Theatre—New Orleans’s first—which was built in 1792 on St. Peter Street between Royal and Bourbon. The building was shuttered intermittently due to poor construction—what one man called “its primitive character”—and illegal gambling, but increased competition forced the property to close in 1810, when it was sold at auction along with its costumes and scenery.

Shortly after Francisqui’s arrival, he founded the New Orleans opera-ballet. He directed the opera troupe, which included the Douvilliers, from 1800 to 1803. They performed at the St. Peter Theatre—New Orleans’s first—which was built in 1792 on St. Peter Street between Royal and Bourbon. The building was shuttered intermittently due to poor construction—what one man called “its primitive character”—and illegal gambling, but increased competition forced the property to close in 1810, when it was sold at auction along with its costumes and scenery.

The Douvilliers and Francisqui persevered despite their lack of a dependable venue. In early 1808, Louis Douvillier became manager of the newly constructed St. Philip Theatre and poached Francisqui from the St. Peter to become its ballet master. Called “vast and grandiose” by one observer, the St. Philip cost $100,000—roughly $2 million today—and could seat up to 700 in a city whose population was only about 17,000, a third of whom were enslaved.

After just four months, the St. Philip Theatre went bankrupt, and its esteemed ballet master Francisqui left the city. Louis’s career was in ruins, and so was his marriage. He and Suzanne separated around this time.

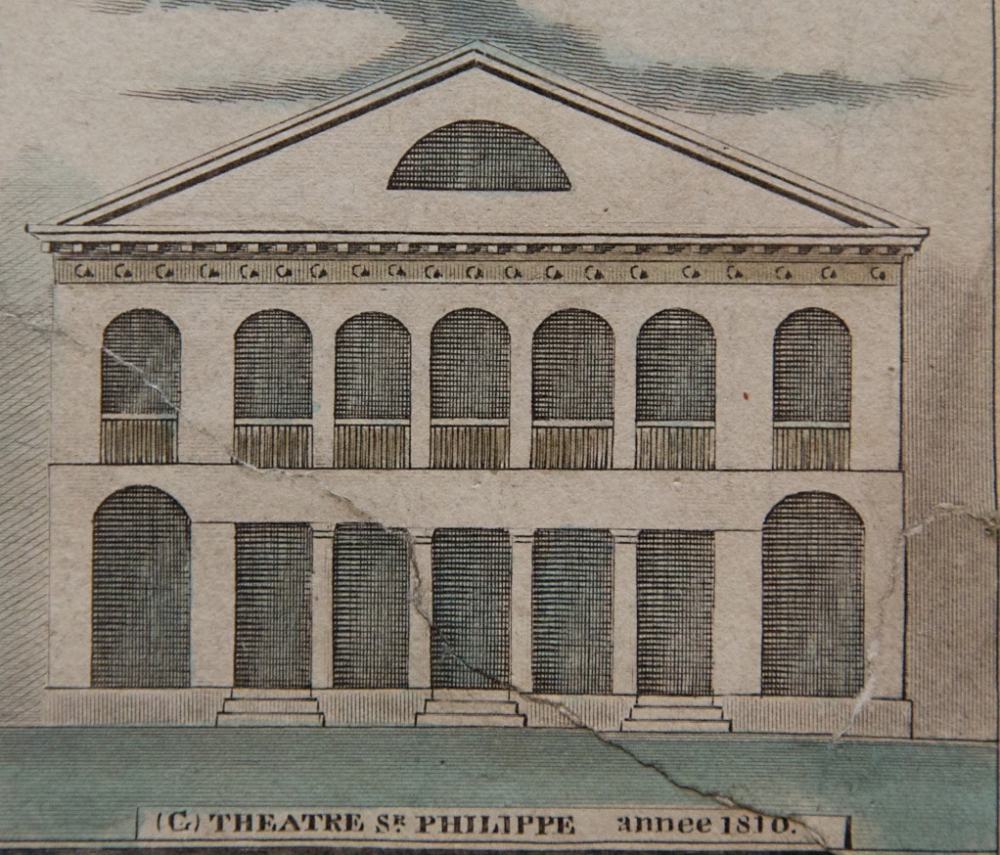

For Suzanne Douvillier, her husband’s failure prompted a new beginning, and a bit of revenge. She was hired as principal dancer and ballet mistress at La Gaité—also known as the Theatre on St. Philip Street—a new venue that opened at the site of the old St. Philip Theatre. Her position put her in charge of training and choreography. The first play she staged there— in the theater that her estranged husband formerly managed—was Echo and Narcissus, or Love and Vengeance (as shown in the an advertisement from Le Moniteur, right). Douvillier played the role of Vengeance.

In addition to being a renowned dancer, Douvillier is credited as the first female choreographer in the U.S. During her tenure at La Gaité—one of three theaters in the city—she diversified the dancers’ repertoire and choreographed original works, such as the Pas de trois (dance for three) in which she danced with two other women while dressed as a man, making her the first known woman to perform a male role in the country.

By 1814 Douvillier’s performing career was nearing its end. Though she no longer intended to dance, she started as a set designer and painter in 1813, another first for an American woman, and she trained her successor, who is known only as Madame Moisson from Charleston, to fill her shoes as principal dancer and choreographer.

The transition, however, was not easy. Two men, Edouard Bertus and one only identified as Chery, arrived in New Orleans in 1814 and tried to wrest choreographic control of La Gaité’s productions from Douvillier. Her grip on her position must have been firm, however, as Chery left town, and Bertus went on to be a social dance instructor. Ironically, Bertus’s career was successful enough for him to construct a grand house—which still stands at 826 St. Louis Street—while Douvillier fell into poverty.

Edouard Bertus's grand house is still standing at 826-828 St. Louis Street. (Image from the Vieux Carré Survey.)

Douvillier wasn’t able to leave the theater for very long. She choreographed new numbers, continued set design, and even got back on the stage, though she was loath to do so; her once beautiful face was so severely disfigured by disease that she performed wearing a mask that covered from just beneath her eyes all the way to her chin.

Douvillier died in poverty in 1826, and though she met an unfortunate end, she had, in her short life, bolstered the emerging performing arts in New Orleans and set new standards for what a woman could achieve in the theater.

Nina Bozak moderated a program at THNOC “In the Spotlight: Stories of Performance Dance in Early New Orleans” on Saturday, September 8, 2018. “In the Spotlight” featured talks from scholars Freddi William Evans, Monique Moss, Maureen Needham-Aldrich, Olga Guardia de Smoak, and Patricia Aulestia, most of whom are also current or former dancers.