After a long struggle by women throughout the United States, the 19th Amendment, which removed gender as a barrier to voting, became law on August 18, 1920. Often, the story of women’s suffrage ends at this crowning achievement. Yet, for many women in the South, the fight did not end there.

After a long struggle by women throughout the United States, the 19th Amendment, which removed gender as a barrier to voting, became law on August 18, 1920. Often, the story of women’s suffrage ends at this crowning achievement. Yet, for many women in the South, the fight did not end there.

While the amendment ostensibly granted all women the right to vote, laws in Louisiana and other southern states continued to disenfranchise African American men and women, rendering suffrage for women at the federal level a moot point. Only with the 1965 passage of the Voting Rights Act was the promise of the 19th Amendment fulfilled.

Here, and in The Historic New Orleans Collection's new virtual exhibition "Yet She Is Advancing": New Orleans Women and the Right to Vote, 1878–1970, we'll look at the people and milestones on the women’s hard-fought journey to access the ballot.

The immediate effects of the 19th Amendment

Between 1920 and 1970, women in New Orleans increased their political participation, often through organizations, but because black and white women faced different challenges, their goals and the strategies they utilized to achieve those goals varied.

While white women were able to gradually but steadily increase voter registration throughout the 1920s, fighting persistent cultural barriers that painted politics as the domain of men, black women faced the more immediate and detrimental challenge to their registration in the form of state laws designed to disenfranchise people of African descent.

Even though the 19th Amendment guaranteed all women the vote by law, it would take until the 1965 Voting Rights Act to secure votes for black women. (THNOC, 1998.42.3.35)

Even though the 19th Amendment guaranteed all women the vote by law, it would take until the 1965 Voting Rights Act to secure votes for black women. (THNOC, 1998.42.3.35)

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) anticipated the issues black women would face in Louisiana after the passage of the 19th Amendment. In a 1920 national report, the NAACP explained that in the South, “not only would no effort be made by the white women’s organizations to train colored women voters but also efforts would be made to prevent colored women from voting.”

Indeed, while the 1921 state constitution removed the word “male” from its description of who could vote, the governing document included laws like the poll tax, qualifications to vote in primaries, and the “understanding clause,” which required a potential voter to interpret a constitutional passage to the satisfaction of the registrar. Orleans Parish registration numbers indicate these laws’ effects: in 1920, almost 1,800 black women registered to vote. This number dropped to a mere 79 in 1922. By 1930, 317 black women were registered, representing just .3 percent of all registered voters in Orleans Parish.

Divergent paths to political participation

By the mid-1930s, more than a decade after the passage of the 19th Amendment, few African American women in New Orleans could exercise their right to vote. Denied this and other civil rights, they continued to fight for equality through their participation in teachers’ unions, civic leagues, and organizations like the NAACP.

Women formed the core of the New Orleans chapter, even though men filled most of the leadership positions. Some women did serve as elected officers, like Eola Lyons-Taylor, head of nursing at Flint-Goodridge Hospital, who sat on the New Orleans NAACP’s executive committee in 1938, and Deborah Johnson Guidry, who was the secretary from 1925 to 1932. Educated at Straight University, Guidry was a teacher, Phyllis Wheatley Club member, community activist, and philanthropist. As NAACP secretary, she spoke out against lynching and urged African Americans to pay their poll taxes.

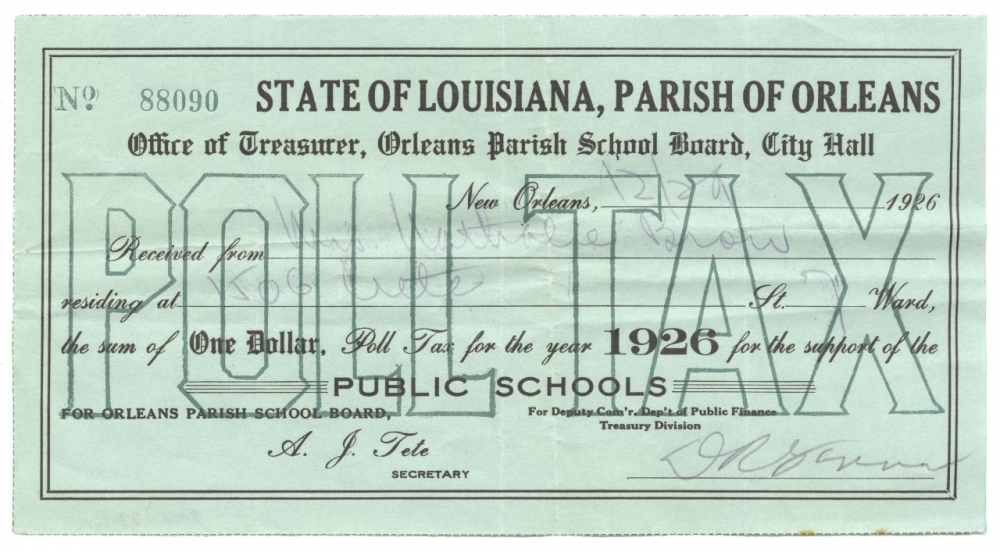

First implemented in Louisiana in 1898, the poll tax was a one-dollar fee required of prospective voters. To register to vote, an individual had to show poll-tax receipts indicating that the tax had been paid for the previous two years. Although the rationale for the tax was couched in populist terms, with the collected funds going to the support of public schools, its true intent was disenfranchisement of the poor.

In an effort to raise awareness about much-needed improvements to black public schools, the New Orleans NAACP encouraged African American teachers, the majority of whom were women, to pay their poll taxes. In 1932, for example, 94 percent of African American teachers paid their poll taxes. The NAACP presented widespread participation as proof of the black community’s civic engagement.

Nathalie Brou received this receipt for paying her poll tax in Orleans Parish in 1926. Poll taxes were first implemented in Louisiana in 1898 and would remain a barrier to poor voters until repealed in 1934. (THNOC, gift of Effie M. Stockton, 2002-97-L.1)

Nathalie Brou received this receipt for paying her poll tax in Orleans Parish in 1926. Poll taxes were first implemented in Louisiana in 1898 and would remain a barrier to poor voters until repealed in 1934. (THNOC, gift of Effie M. Stockton, 2002-97-L.1)

The tax was repealed in 1934, one of many reforms initiated by Huey P. Long, but voters were still required to sign a pollbook at the local sheriff’s office. State voter rolls expanded, with the number of registered white women nearly doubling, but African Americans were denied access to pollbooks through a variety of tactics—not least, intimidation. By the time a 1940 law abolished the pollbook requirement, only 897 black Louisianians were registered to vote. The number of black women registered in Orleans Parish reached a low of 66.

For most white women in the city, the discrimination faced by black New Orleanians remained all but invisible in the 1930s and 1940s. Although slow to join the electorate at first, by the early 1930s white women were registering to vote in increasing numbers. Some women, mostly among the upper and middle classes, began organizing against the famously corrupt Huey P. Long machine.

In 1933, the Women’s Committee of Louisiana, led by Hilda Phelps Hammond, initiated a multiyear crusade against Long. White women’s efforts over the next three decades to promote political reforms, educate voters, and support candidates largely unfolded in a segregated space—although a few figures, like Rosa F. Keller, who fought to desegregate New Orleans’s public transportation and library systems, worked with black organizers and leaders.

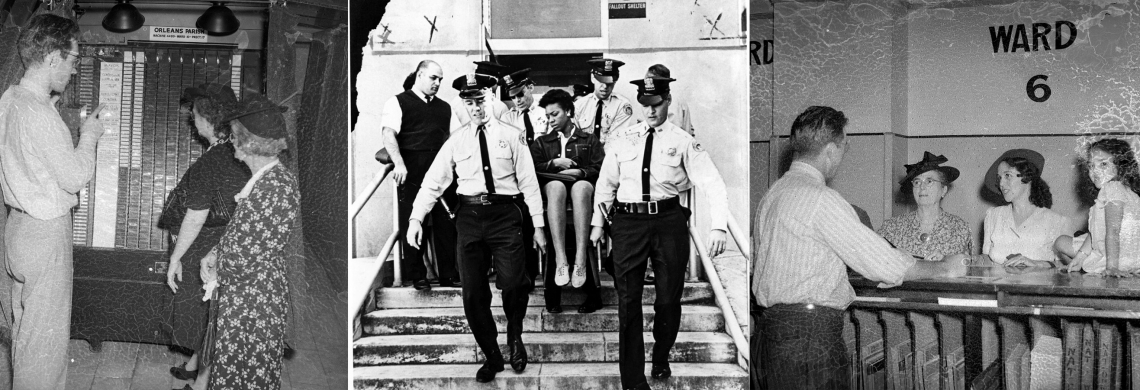

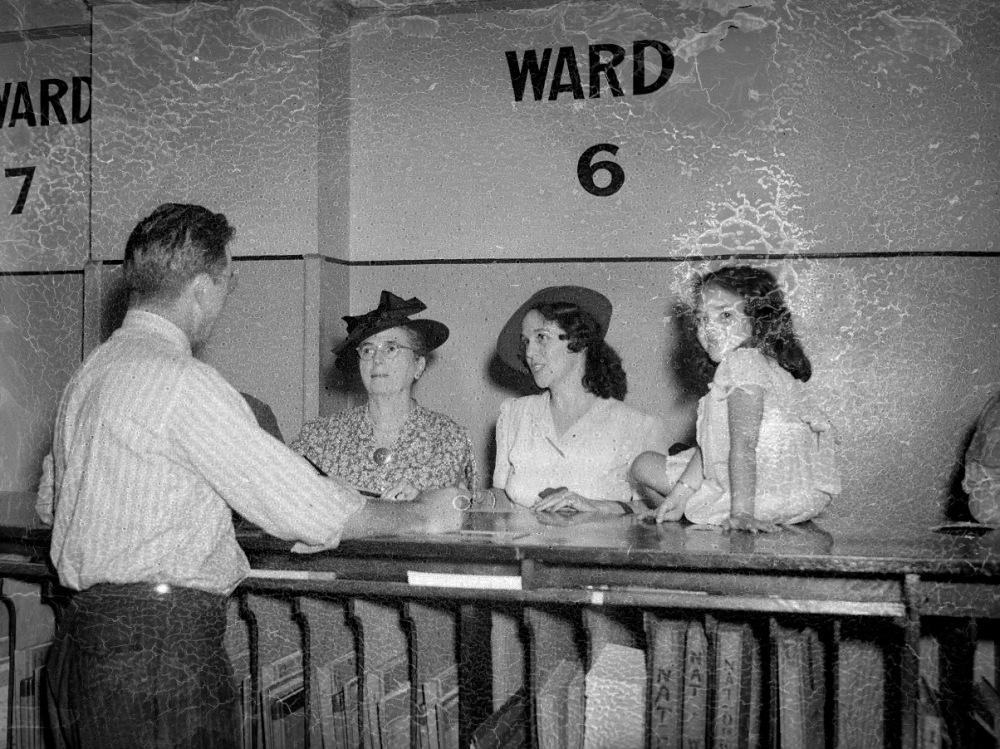

Women were responsible for driving many reforms in the 1930s and ‘40s, including moving polling places to public buildings. (THNOC, 1998.42.3.33)

Women were responsible for driving many reforms in the 1930s and ‘40s, including moving polling places to public buildings. (THNOC, 1998.42.3.33)

After working with the Women’s Committee of Louisiana and the Women’s Division of the Honest Election League to monitor the polls on election day, Martha Gilmore Robinson founded the Woman Citizen’s Union (WCU) in 1934. The WCU focused on voter education, encouraged white women to register to vote, and worked on election reforms like the use of public buildings for polling places and voting machines.

In 1942, the WCU officially disbanded to become the New Orleans branch of the League of Women Voters (LWVNO), with Robinson as president. The league led a two-year voter registration drive during WWII, inspected precincts to combat corruption, and expanded its membership among white middle-class women throughout the city.

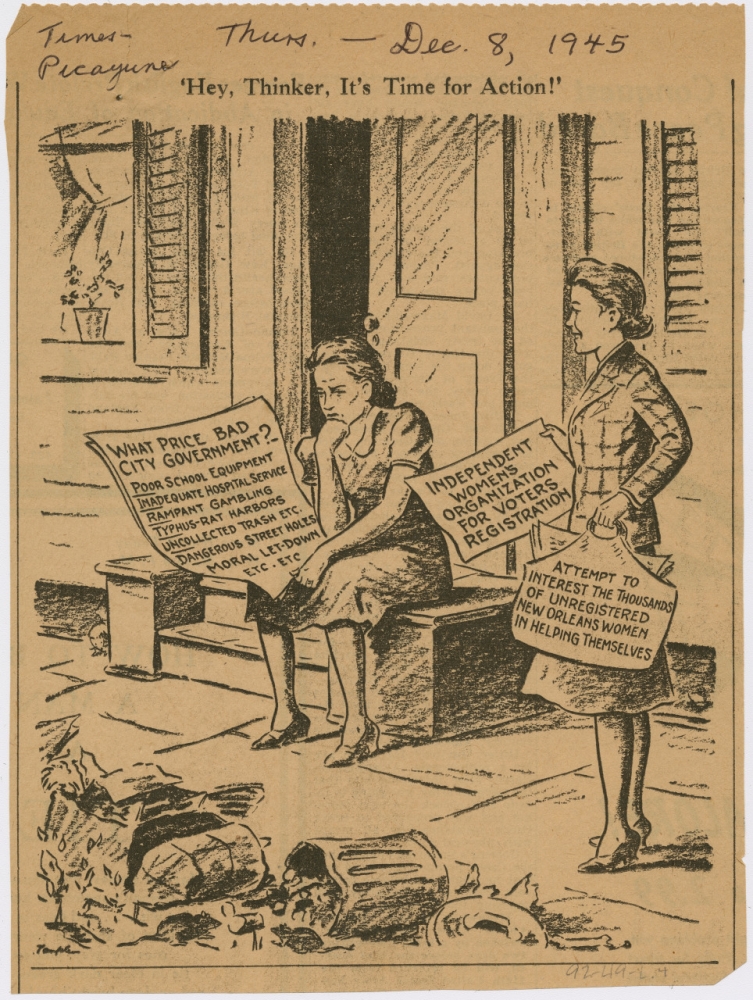

Unlike the nonpartisan WCU-turned-LWVNO, the Independent Women’s Organization (IWO) formed specifically to support the election of reform mayoral candidate deLesseps “Chep” Morrison in 1945. IWO leader July Waters and other founders of the group had worked to elect anti-Long gubernatorial candidate Sam Houston Jones in 1940. Their prior experience canvassing, inspecting voter rolls, and monitoring polling precincts to detect illegal election activities proved instrumental in the IWO’s success with the 1946 Morrison campaign.

In the weeks leading up to election day, IWO members registered over 4,000 new white women voters, canvassed for Morrison, and led a “March of Brooms” down Canal Street to symbolize their campaign slogan, “A Clean Sweep with Morrison.” On election day, 400 women, recruited by the IWO, served as poll watchers. The organization’s efforts paid off when Morrison defeated incumbent Robert Maestri, a Long ally, by 4,000 votes.

A cartoon for the Independent Women’s Organization lists political issues and urges the registration of women voters in New Orleans. The organizers of the IWO put their might behind reform candidates, including gubernatorial candidate Sam Houston Jones and deLesseps “Chep” Morrison. (THNOC, gift of Mary Morrison, 92-49-L.4)

A cartoon for the Independent Women’s Organization lists political issues and urges the registration of women voters in New Orleans. The organizers of the IWO put their might behind reform candidates, including gubernatorial candidate Sam Houston Jones and deLesseps “Chep” Morrison. (THNOC, gift of Mary Morrison, 92-49-L.4)

The avenues that upper- and middle-class white women took towards expanded involvement in electoral politics were not open to African American women in the interwar period. Black women’s goals were both more basic and more expansive—to exercise their rights as citizens of the United States and to end racial inequality. Between the Great Depression and WWII, African American women not only continued to attempt to register to vote, they also sought pay equity for teachers, entrance to whites-only universities, and improvements to their working conditions, their children’s schools, and their neighborhoods.

The movement gains momentum

After WWII, the fight for equality entered a new phase of public demonstration and civil disobedience. This, combined with NAACP successes in the courtroom, ushered in the civil rights movement. Whereas previous waves of black activism had focused mostly on ending discrimination within the “separate but equal” framework (pressing for equal pay for black teachers rather than for integrated schools, for example), the objectives of civil rights activists shifted in the mid-1950s through the 1960s to that of wholly dismantling Jim Crow segregation and claiming full citizenship for all people of African descent.

Full citizenship required access to the ballot box. In 1944, the Supreme Court decision in Smith v. Allwright, pursued by the NAACP, had a profound effect on black voting rights and overall political participation across the South. Prior to the decision, southern states, including Louisiana, allowed only whites to vote in primaries, thus shoring up white supremacy and guaranteeing the political powerlessness of African Americans.

With Smith v. Allwright, the court declared the all-white primary unconstitutional. In New Orleans, the number of registered African American voters expanded significantly in the years following the decision, a growth that had much to do with the organized initiatives of black residents. African American women voters, for example, increased from 221 in 1944 to over 1,300 in 1946. By 1952, more than 12,000 black women were registered in Orleans parish.

In this video from THNOC’s NOLA Resistance Oral History Project, Raphael Cassimere and Katrena Ndang discuss voter registration efforts.

In the wake of the Smith decision, African Americans redoubled both individual and collective efforts to register to vote. Leading up to the 1956 Louisiana governor’s race, the NAACP initiated a large, multiorganization voter-registration campaign in New Orleans.

A cohort of women managed the voter drive, including Ethel Young, president of the New Orleans Parent-Teachers’ Association Council; Oralean and Joyce Davis, NAACP members and sisters of Orleans Parish Progressive League founder Rev. A. L. Davis; and nurses at Flint-Goodridge Hospital. Leontine Goins Luke participated in the campaign as a member of the Ninth Ward Civic and Improvement League, an organization formed in 1945 to pursue voter registration for black residents of the Ninth Ward.

Nurses from the Flint-Goodridge Hospital helped manage a voting drive leading up to the 1956 governor’s race. (The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.7128)

Nurses from the Flint-Goodridge Hospital helped manage a voting drive leading up to the 1956 governor’s race. (The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.7128)

Under the leadership of Katie Whickam, a beauty school owner and NAACP member, the New Orleans chapter of the Young Women’s Christian Association also initiated a voter registration drive in late 1954. To support this effort, and because the LWVNO remained an all-white organization, Whickam and other African American women founded the Metropolitan Women’s Voters’ League (MWVL). Members knocked on doors to promote registration and organized voter education workshops, prompting the Louisiana Weekly to recognize the MWVL’s work as proof that “women of the community are going to participate like never before.”

And participate they did: African American women formed the center of the growing civil rights movement in the city. Women like Leontine Goins Luke, who worked to secure voters’ rights, understood that voting and integration of schools and public places all went hand-in-hand as part of the same struggle for full citizenship. From renewed efforts to register black voters to desegregating public schools and conducting sit-ins, women effected real change in New Orleans over the next decade.

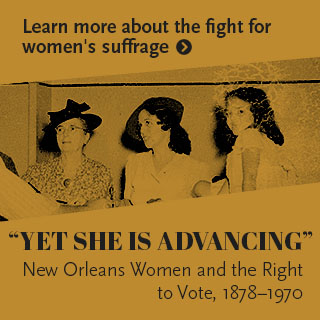

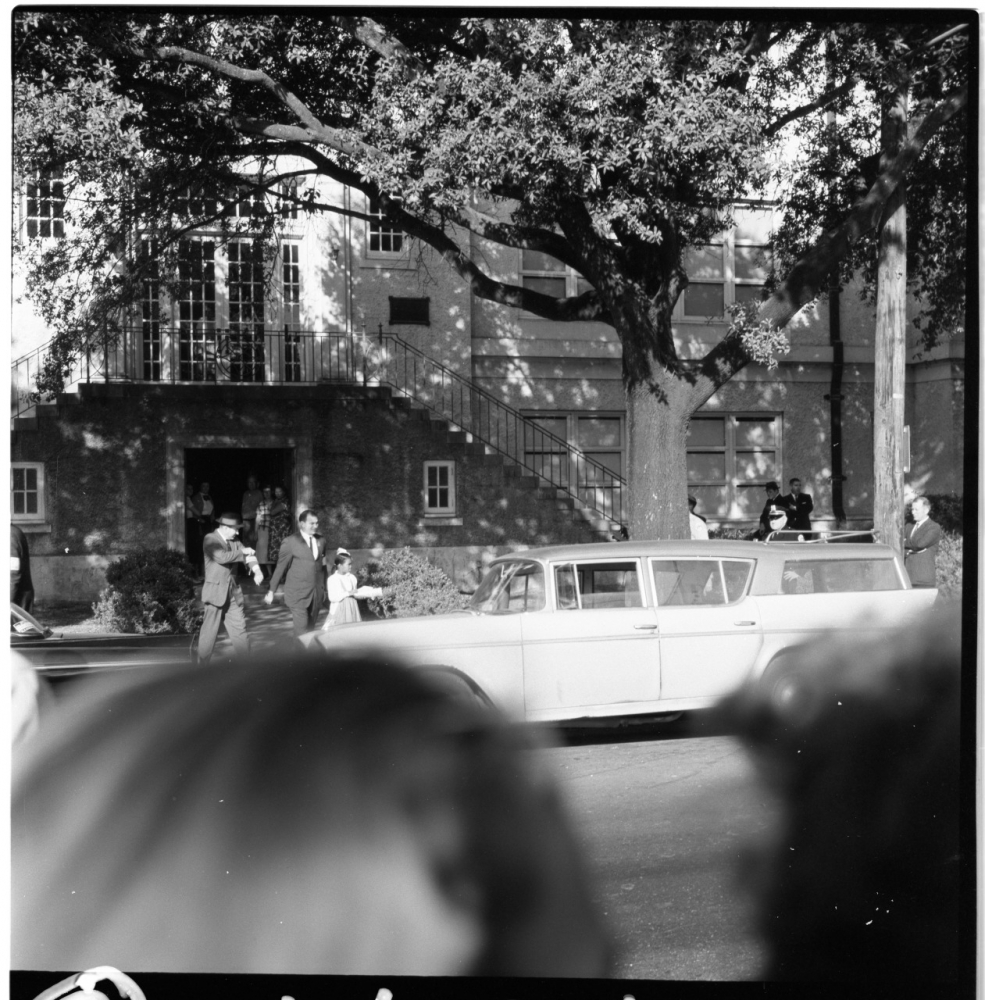

Tessie Prevost is escorted from McDonogh 19 school. Prevost was among four girls who first desegregated New Orleans’s public schools in November 1960. (Jules Cahn Collection at THNOC, 1996.123.1.107)

Tessie Prevost is escorted from McDonogh 19 school. Prevost was among four girls who first desegregated New Orleans’s public schools in November 1960. (Jules Cahn Collection at THNOC, 1996.123.1.107)

Following the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which declared the principle of “separate but equal” unconstitutional, black women petitioned the Orleans Parish School Board to implement the ruling. Six years later, when four African American girls—Leona Tate, Gail Etienne, Tessie Prevost, and Ruby Bridges—desegregated two white schools in the Ninth Ward, Luke and the Ninth Ward Civic and Improvement League provided support for the girls and their families. Some white women also used their experience as advocates for women voters to support the desegregation cause.

A number of white women’s organizations, including the IWO and the LWVNO, openly supported the Brown decision. When Louisiana Governor Jimmie Davis attempted to close the schools to avoid federally mandated integration in 1959, LWVNO member Rosa F. Keller helped found Save Our Schools (SOS) to keep public schools open. SOS members distributed information to challenge segregationists’ school-closure arguments and organized carpools to escort the few remaining white children enrolled in the desegregated William Frantz Elementary School.

As the fight to desegregate New Orleans’s public schools intensified, a younger generation of activists began to mobilize against segregation in other public spaces. Students from local colleges, both black and white, established a New Orleans chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in the summer of 1960. Most of the original founders of CORE in New Orleans were women, including sisters Oretha and Doris Jean Castle; Dodie Smith; Julia Aaron; Sandra Nixon; and Alice, Jean, and Shirley Thompson.

The “strong-willed and dynamic” Oretha Castle became CORE president in 1961, and by 1964 the chapter’s leadership consisted entirely of African American women.

CORE is perhaps best known for the nonviolent, direct-action tactics that attracted national press attention, like sit-ins at segregated businesses and lunch counters in New Orleans. Equally important to CORE’s mission were mass voter registration and education campaigns in rural parishes throughout Louisiana. As leaders, organizers, activists, and, increasingly, as voters, black women in New Orleans were part of a wave of pressure that helped secure passage of the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Doris Jean Castle is shown being forcibly removed from City Hall during a protest of its segregated cafeteria 1963. (Courtesy of the Times-Picayune)

Doris Jean Castle is shown being forcibly removed from City Hall during a protest of its segregated cafeteria 1963. (Courtesy of the Times-Picayune)

Advancing with the vote

The Voting Rights Act ended the discriminatory practices that prevented black Louisianians from exercising their constitutional right to vote. Organizations that had originally formed to assist black New Orleanians navigate the byzantine voter-registration process shifted their focus to educating newly registered voters. The long-running Louisiana League of Good Government (LLOGG) serves as a fitting example.

Sybil Morial founded the LLOGG with a group of friends in 1963. Morial recounts in her memoir how she attempted to join the LWVNO in 1961 but was denied membership, as the organization was still segregated at the time. (The LWVNO integrated a few years later.) The interracial LLOGG started out by leading voter-registration workshops at churches and senior centers but moved on over the following 40 years to provide voter education, run registration drives, and host candidate forums.

A 1965 image shows Iris Kelso, Lindy Boggs, Sybil Morial, and Mrs. Waldo Bernard at the annual membership banquet for the Louisiana League of Good Government (LLOGG). (THNOC, 2004.0059.30)

A 1965 image shows Iris Kelso, Lindy Boggs, Sybil Morial, and Mrs. Waldo Bernard at the annual membership banquet for the Louisiana League of Good Government (LLOGG). (THNOC, 2004.0059.30)

By 1970, the majority of registered voters in New Orleans were women, and both black and white women were advancing from political organizing to elected positions.

Educator and civil rights activist Dorothy Mae Taylor became the first black woman elected to the Louisiana House of Representatives in 1971. She went on to be the first African American woman to hold a state cabinet position and to serve on the New Orleans City Council. In 1973, Lindy Boggs became the first Louisiana woman elected to Congress. She continued to represent the state until 1991. Both Taylor and Boggs used their positions of power to advocate for women’s rights and racial equality.

Dorothy Mae Taylor became the first black woman elected to the Louisiana House of Representatives in 1971. Taylor is pictured here, surrounded by reporters, that same year. (THNOC, 2020.0084.1)

Dorothy Mae Taylor became the first black woman elected to the Louisiana House of Representatives in 1971. Taylor is pictured here, surrounded by reporters, that same year. (THNOC, 2020.0084.1)

The passage of the 19th Amendment was a major victory for the women’s suffrage movement, but it took another 45 years for African American women to achieve full enfranchisement. In commemorating the 100th anniversary of the amendment’s ratification, we recognize the perseverance of the many community activists and civil rights leaders who refused to be denied their constitutional rights as American citizens and, in turn, brought the United States closer to its democratic ideals.