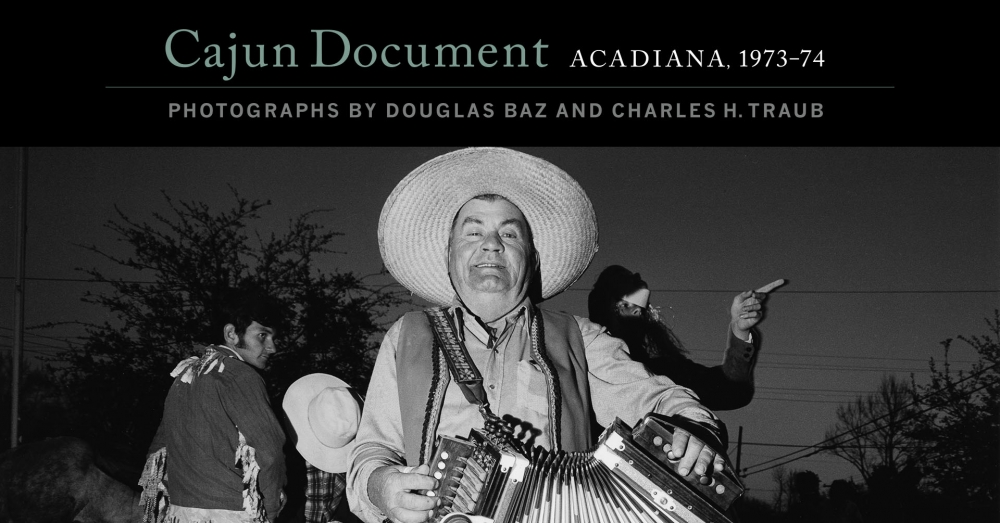

South Louisiana is a diverse place with varied traditions, cultures, cusine, and peoples. In conjunction with The Historic New Orleans Collection's book and exhibition Cajun Document: Acadiana, 1973–74, the museum's Visitor Services staff have explored one of these groups, Cajuns, and how that term came to dominate the cultural conversations around the region.

THNOC Visitor Services staff members and experts on Cajun and Creole identity delve into the people of south Louisiana.

The people who would come to be known as Cajuns are the descendants of some of the earliest French settlers in the New World, specifically in what is now the Canadian Maritime Provinces. Migration to this area, then known as Acadia, centered around the settlements at Port-Royal in 1604 and later at Grand-Pré, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Acadians thrived in their new homes fishing and farming. They lived alongside the Mi’kmaq who largely adopted the French settlers’ Catholic faith. This peaceful coexistence included cooperation and often marriage. However, the Acadians would often find themselves in conflict with their neighbors to the south, the British.

Conflict between France and England occurred frequently throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. This history of warfare would culminate in Le Grand Dérangement, the expulsion of the Acadians from Canada, which began in 1755.

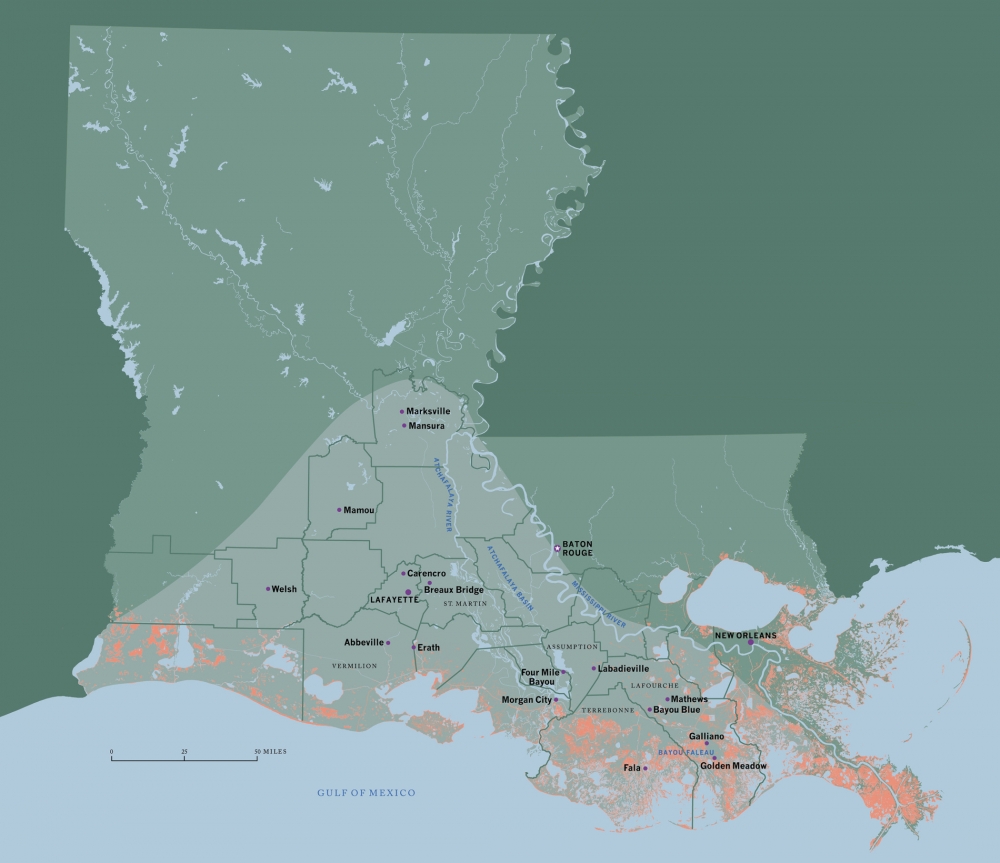

A map of Louisiana features the Acadiana region in light green. (Design by Tana Coman, data courtesy Louisiana Geological Survey, LSU)

Acadian exiles soon found themselves scattered throughout North America in British colonies as well as in French colonial holdings in the Caribbean. Many of these exiles found their way back to France. France, however, was no longer home to many Acadians. This restlessness, coupled with Spain’s difficulty in settling their new Louisiana territory, prompted the Spanish government to invite and incentivize Acadian resettlement in South Louisiana in 1788.

The 12 stories below cover what happened next, when Acadians arrived in Louisiana and started to settle among, and intermix, with local populations. For more to this complicated story, visit our First Draft article on the differences—and the debate as to whether there is a difference—between Cajuns and Creoles.

1. Cajun French

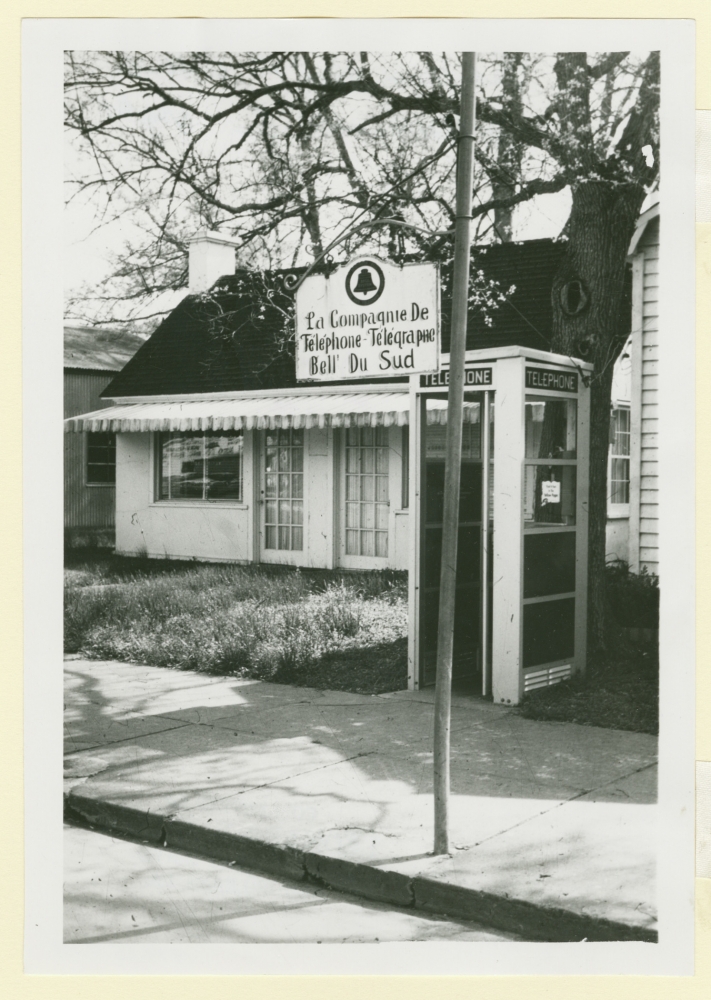

A Bell Telephone Company sign in St. Martinville is written in French in this 1964 image. (THNOC, 1974.25.4.108)

Often, when people outside of Louisiana picture a Cajun, the image they conjure comes complete with a ridiculous accent. Despite this cartoonish depiction, Cajuns have traditionally spoken a language that is distinct from the standard French that was spoken in France.

Cajun French’s path forked from that of Modern Standard French (MSF) when the first French colonists in Acadia embarked to the New World. The majority of Acadian settlers came from Aquitaine, where the Occitan dialect is still common; Brittany, whose dialect has Celtic influences; and Normandy, which was settled by Norse-speaking Vikings. These regional dialects differed from the Parisian dialect that would become MSF.

Settlement in Acadia began in the early 17th century, some 30 years before the founding of the Académie Française, the standard bearer of MSF. The distance between French Canada and the mother country insulated the developing Acadian French from the standardization movement in France proper. Concurrently, the Acadian willingness to adopt loan words from their neighbors added further distinctions to an already differing way of speaking. This insulation and willingness to add local vocabulary continued after the Acadians settled in Louisiana creating a language all its own.

2. Cajun Catholicism

Photographers Douglas Baz and Charles H. Traub snapped this image of a boy riding a bicycle in front of a St. Martin Parish church during their stay in Acadiana in 1973 and '74. (THNOC, © Douglas Baz and Charles H. Traub, 2019.0362.108)

In south Louisiana, unlike most of the southern United States, Catholicism is the norm, and its sacraments, feasts, and calendar permeate many aspects of life. Here, under the influence of the region’s Latin European and African heritage, unique manifestations of the faith have emerged. Various Catholic holidays are celebrated in distinctive ways in south Louisiana, from the region’s rural Mardi Gras traditions, to the tradition of washing and painting the tombs and crypts in local cemeteries for All Saints’ Day. There are local devotions and prayers, and personal expressions of the faith that also abound. Drive through many neighborhoods, and you will see yard grottoes, small personal shrines most often featuring statues of the Virgin Mary.

Then, of course, there are events like Fête Dieu du Teche, an annual eucharistic boat procession down the Bayou Teche. Led by a boat displaying the consecrated host for veneration, community members join the procession with their personal vessels. The 38-mile trip is also a way of honoring the community’s history: in 1765 exiled Acadian Catholics first journeyed down the Bayou Teche to their new home, and the presence of their faith remains strong today.

3. Evangeline

This statue of Evangeline in St. Martinville is emblematic of the character's place within the Acadian backstory. (THNOC, 1974.25.24.115)

After more than a century of calling Louisiana home, Acadian descendants found themselves in want of an origin myth, something literary that could historicize and glorify their coming to the American South. They found both that myth and a heroine in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1847 poem "Evangeline, A Tale of Acadie." In the poem, the eponymous Evangeline is separated from her beloved Gabriel during Le Grand Dérangement of 1755 only to reunite decades later at Gabriel’s deathbed in Philadelphia. Historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage argues that Cajuns, who had already faced decades of ostracism and prejudice in their new Louisiana home, “adopted Longfellow’s Evangeline as their Joan of Arc.”

A tragic heroine, Evangeline proved to be the perfect symbol for the Acadians’ perseverance in the face of their history of misfortune and displacement. The Evangeline legend was particularly popular in the first half of the 20th century. In addition to the creation of an Evangeline statue in St. Martinville and a state historic site nearby, the moniker graces numerous businesses and brand names in south Louisiana.

4. Susan Anding and the "Evangeline girls"

A group of "Evangeline girls" is pictured with First Lady Lou Henry Hoover at the White House in 1930. (THNOC, gift of Mary Aldigé Brogden, 96-47-L.2)

As the US launched into the Gilded Age, Louisianans of Acadian descent wanted to make sure that their history, language, and culture persisted through the economic and social changes marking the turn of the 20th century. This revival of Acadian culture hit its stride in the 1920s when Susan Evangeline Walker Anding sought to make this heritage nationally known and bring visitors to south Louisiana. Proponents of this cultural campaign promoted their culture as "Acadian" rather than "Cajun," which was largely used to denigrate working class people at the time.

Although not technically a Louisiana Acadian herself, Anding used fundraisers and radio broadcasts to garner support for a monument to Evangeline, Longfellow’s poetic heroine. Anding even paraded “Evangeline girls"—young girls dressed in 18th-century garb—at the Republican and Democratic National Conventions in 1926 to better nationalize awareness of Acadian culture. Anding’s work, along with the work of other like-minded activists, secured the history of Acadians in the broader American story—both the pride in coming from elsewhere and the desire to contribute to one’s adopted home. Her zeal for Acadian culture laid the groundwork for an elite-led revival of Cajun pride in the latter part of the 20th century.

5. Dudley LeBlanc's journeys back to Acadia

A series of buses carry Louisianans returning from a trip to Canada organized by Dudley LeBlanc. (The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.89.7405)

Dudley LeBlanc gained prominence as an advocate for Acadian culture in the 1920s and 1930s, around the same time as Susan Anding, but unlike Anding, he was an Acadian. While Anding’s aim was to tell the nation about the presence of Acadians, LeBlanc wanted Acadian descendants in Louisiana to be more in tune with their own past. A traveling-salesman-turned-politician, LeBlanc played up his Acadian heritage with French speeches and southern Louisiana food. However, LeBlanc’s nostalgia for the Acadian past also required a geographic shift to the Acadian homeland in Canada.

LeBlanc forged relationships with descendant communities throughout the reach of the Acadian diaspora, though he maintained that those who settled in Louisiana were the “most romantic and tragically unfortunate of all the…exiles.” In addition to encouraging spoken French, Catholic sensibilities, and diplomatic relations among the refugees’ descendants, LeBlanc also recognized the power of symbolism, particularly that of the Acadians’ adopted heroine Evangeline. In August 1930, he organized the first of multiple pilgrimages from Louisiana to Canada that included 25 “Evangeline girls” and a stop at the White House.

6. CODOFIL, and the reemergence of the French language

A CODOFIL guide ends with the signature of James "Jimmy" Domengeaux, the organization's first president. (THNOC, gift of St. Mary's Dominican College, 84-1168-RL)

In 1968 Louisiana lawmakers with names such as Mouton, Broussard, Breaux, and LeBlanc scored a cultural preservation victory with the passage of Act No. 409, which created le Conseil pour le Développement du Français en Louisiane, better known as the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL). This, and other laws passed that year, attempted to reverse decades of government-enforced English-only language policies, which had detrimental effects on the use of French in Louisiana.

CODOFIL sought to perpetuate the French language primarily through education, by hosting teachers from France, Canada, and other Francophone countries. Its first president was charismatic Lafayette attorney and former congressman, James "Jimmy" Domengeaux, who represented an elite movement to instill pride in, and challenge misrepresentations of, Cajun culture. Domengeaux was adamant that standard French should be taught as opposed to Louisiana (Cajun) French, once commenting, “There's nothing wrong with our French that a little grammar won't cure.”

The establishment of CODOFIL some two hundred years after the first Acadians arrived in Louisiana was a watershed moment, but one fraught with controversy over bourgeois notions of Cajun identity, teaching regional dialects and vocabulary, and the inclusion of non-Cajun-identified French speakers. After more than a half-century, the organization now actively promotes French "as it is found in Louisiana," by individuals who identify as French, Cajun, Creole, and Native American, including Houma, Atakapa-Ishak, Chitimacha, and Tunica-Biloxi tribes. CODOFIL, still headquartered in Lafayette, continues to offer French-immersion scholarships, placement for native Louisiana French teachers, promotion of bilingual businesses, and a multimedia project called Radio Jeunesse Louisiane.

7. The grassroots movement

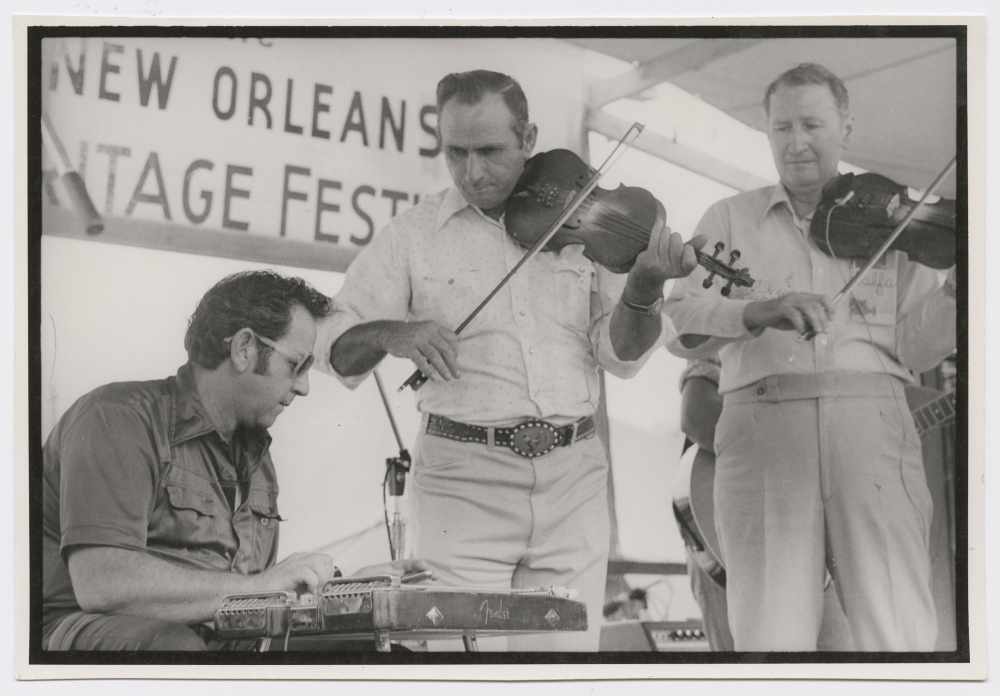

The Balfa Brothers play at the 1979 New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. Dewey Balfa is pictured on the right. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith ©THNOC, 2007.0103.4.697)

When a journalist asked Edwin Edwards what other Cajuns thought of his ascension to the governor’s seat in 1972, he replied: “They probably think, ‘He has proved that a Cajun is as good as anybody else.’” Edwards’ campaign motto, “Cajun Power,” proclaimed the inherent value of this ethnic identity at a time when many Cajuns realized that their Americanization since the World War II era had come with a cost. Inspired, in part, by the Black Power Movement, a grassroots Cajun cultural revival arose in the late 1960s and early 1970s, alongside an elite-led movement represented by Jimmy Domengeaux and CODOFIL.

Activists, including Barry Jean Ancelet, Zachary Richard, Dewy Balfa, and a host of others worked to preserve all components of Cajun culture—language, food, music, crafts, and other traditions. Unlike proponents of CODOFIL, the grassroots activists celebrated the use of Cajun French. The cultural activism of this period successfully brought renewed pride and empowerment to south Louisianians who identified as Cajun, oversaw a flourishing of Cajun cultural production, and promoted heritage tourism in the region by introducing “Cajun country” to the nation. As historian Shane Bernard states: “While Cajun pride soared in southern Louisiana, mainstream America ‘discovered’ this unique culture in its own backyard.”

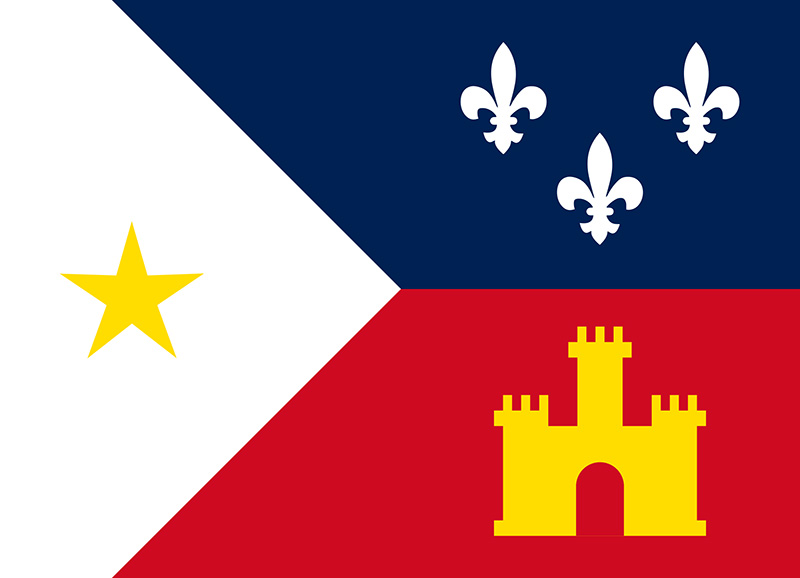

8. Flag of Acadiana

Designed in 1965 by Professor Thomas J. Arceneaux of the University of Louisiana Lafayette, the Flag of Acadiana is a common site on homes, buildings, cars, and flagpoles throughout the state. It also serves as the flag of the city of Lafayette, Louisiana. The flag was formally adopted by the Louisiana legislature on July 5, 1974.

Its design pays homage to the kingdoms of France and Spain as well as to the Acadians’ seafaring and Catholic histories. The blue field with its three white fleurs-de-lis recognizes the French origins of the Acadians by mimicking the Royal Standard of France at the time of the Acadians’ departure, the familiar blue field and three gold lilies. The red field features a gold castle in recognition of the role played by Spain in the journey of the Acadians to Louisiana. Finally, the gold star placed in a white field, often called a Stella Maris, or Star of the Sea, pays homage to Our Lady of the Assumption, patroness of the Acadian people.

The flag of Acadiana is not to be mistaken for the Acadian Flag. This banner, a French tricolor with a gold star in the blue stripe, was adopted by the Second Acadian National Convention in 1884. The design anachronistically uses the flag of the French Republic which was not in use until after Le Grand Dérangement and the Acadian settlement of Louisiana.

9. "Acadiana"

A Vermillion Parish couple is pictured in this image by Douglas Baz and Charles H. Traub from 1973 or '74. (THNOC, © Douglas Baz and Charles H. Traub, 2019.0362.16.1)

In 1971, the Louisiana legislature officially designated 22 parishes of south Louisiana “Acadiana.” Devised by an economic development group based in Lafayette, Acadiana serves as a branding device to promote trade and Cajun heritage tourism in the region. The development group came up with the idea to create a district, but it did not invent the term “Acadiana.” According to historian Shane Bernard, a newspaper in Acadia parish, the Crowley Daily-Signal, used “Acadiana” in the late 1950s to describe news and events relative to the parish.

The name became popular, however, after KATC-TV, a Lafayette broadcaster, began using it in the 1960s. The station’s general manager landed on the name after reading a typo on a piece of mail that added an “a” to the company’s name, Acadian Television Corporation. The spread of the term in south Louisiana coincided with the growing Cajun cultural revival that brought renewed pride in Cajun identity and national attention to the region. Although highly successful as a marketing tool, the “Acadiana” designation masks the cultural and demographic diversity of the area of which it is attached. For more on this diversity, visit our recent story about the intertwined histories of Cajuns and Louisiana Creoles.

10. The Cajun Craze

Chef Paul Prudhomme is pictured at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival in 1982. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith, ©THNOC, 2007.0103.8.669)

By the end of the 1970s, Cajuns were heavily involved in the maintenance and preservation of their traditions and identity. This led to an increased acknowledgement of Cajuns by people outside of south Louisiana. During the 1980s and ‘90s, this recognition led to the commercialization of Cajun culture, especially by the food and film industries. This period saw a veritable “Cajun Craze” sweep the nation.

The popularity of Paul Prudhomme, the first Cajun chef to achieve worldwide fame, and Louisiana fast-food chain, Popeyes, led to the addition of “Cajun” dishes to menus across the country. Foods like pizza, french fries, sushi, and other edible products labeled “Cajun” were overly spiced concoctions that would not be found on any actual Cajun dinner table. It did not take long for the film industry to join the Cajun exoticism bandwagon. Films such as Southern Comfort and The Big Easy were among those set in Louisiana, which highlighted its culture and scenery, but also played up Cajun stereotypes and often confused New Orleans with Acadiana.

11. The Second Cajun Revival

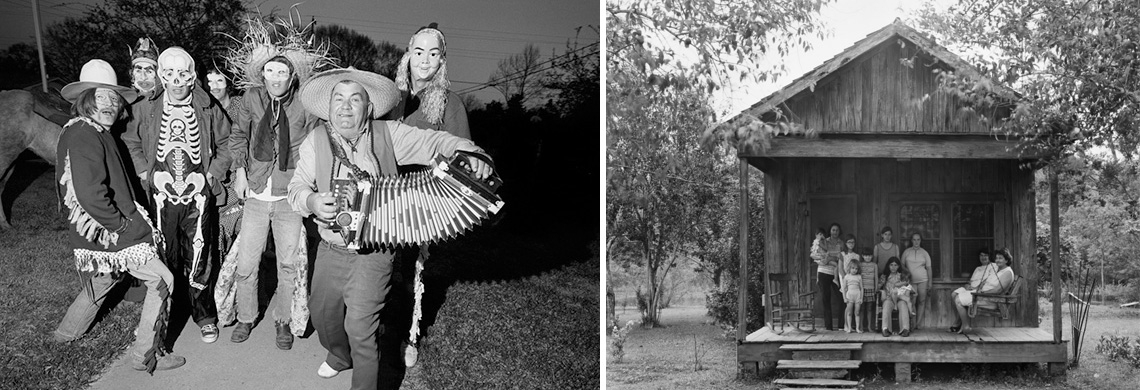

Natahan Abshire (foreground) is shown with a group of musicians at a Mardi Gras celebration in 1973 or '74. (THNOC, © Douglas Baz and Charles H. Traub, 2019.0362.97)

In the 1980s and ‘90s, while the nation consumed a watered-down version of Cajun culture at best, Cajuns in south Louisiana experienced a renewed surge in ethnic pride, led by writers, artists, and especially musicians. Since Dewey Balfa’s performance at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival brought national recognition to Cajun music, musicians served as key players in the cultural revival movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

At the end of the 20th century, a new generation of musicians, including Wayne Toups, Michael Doucet, and Zachary Richard, as well as the band BeauSoleil, and Bruce Daigrepont rose in prominence. They headlined folk and jazz festival stages all over the country, while Cajun music made cameos on both soundtracks and television commercials.

In 1987, a new event, Festival International de Louisiane, began to celebrate the distinct French heritage of Louisiana, melding its food, music, and language. The festival was founded to help the Acadiana region bounce back economically after a 1980s oil bust by bringing more tourists to the area. It worked beautifully: more than 300,000 people attend the festival today.

12. The Cajun diaspora

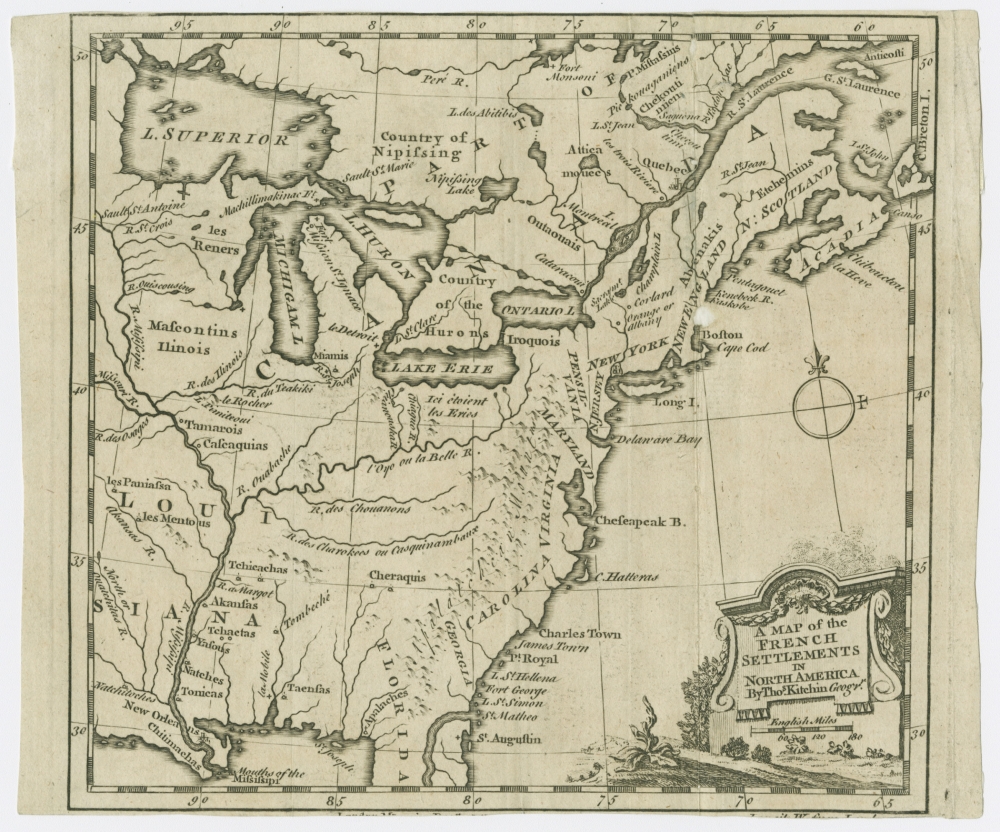

A 1747 map shows French settlements in North America, including Acadia (top right) and Louisiana (bottom left). (THNOC, 2018.0394)

Since the 3,000 or so Acadians resettled in south Louisiana in the late 18th century, they have evolved into an ethnic group of their own with a distinctly Cajun identity. In the 20th century, familial migrations, changing industry, and storms have all led to the creation of a Cajun cultural diaspora. After the oil industry crash of 1981, many Cajuns left Louisiana in search of financial stability. Cajuns had previously settled in Texas to cultivate rice and work on railroads, but by the end of the 20th century, the Texas economy was booming again with oil money, and many relocated there. Cajuns also headed eastward. The 2010 Census revealed that there are over 100,000 self-identified Cajuns living in Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida.

Smaller pockets of Cajun culture have popped up in less predictable places as well. For example, University of Louisiana Lafayette scholar Mark DeWitt has extensively documented the Cajun music and dance scene in northern California, a result of family groups settling in the area while simultaneously holding on to Cajun cultural elements. In addition to events and festivals in California, there are long-standing annual Cajun music festivals in the northeast that boast of offerings of Louisiana music and food such as The Great Connecticut Cajun and Zydeco Music & Arts Festival and the Strawberry Park Cajun Zydeco Festival in Rhode Island. These festivals are known to draw regional fans, francophones, and Canadians who can drive a few hours to seek Acadian-descendant connections.

The authors of this article would like to acknowledge the following sources: Finding Cajun, directed by Nathan Rabalais; The Cajuns: Americanization of a People by Shane Bernard; “Memory and Acadian Identity” by W. Fitzhugh Brundage in Where these Memories Grow: History, Memory, and Southern Identity; “‘Don’t call me a Cajun’: Race and Representation in Louisiana’s Acadiana Region” by Alexandra Giancarlo in Journal of Cultural Geography; “Cajunization of French Louisiana: Forging a Regional Identity” by Cécyle Trépanier in The Geographical Journal; “Creole Is, Creole Ain’t: Diachronic and Synchronic Attitudes toward Creole Identity in Southern Louisiana” by Sylvie Dubois and Megan Melançon in Language in Society.

Explore Acadiana of the 1970s with THNOC's book and exhibition Cajun Document.