For the last two decades The Historic New Orleans Collection has methodically built one of the most extensive Tennessee Williams collections in the world, and thanks to a generous endowment from the late Fred W. Todd, the holdings continue to increase. Hundreds of items chart the development and influence of Williams’s classic play A Streetcar Named Desire. The wide range of materials features objects such as the typewriter Williams used to write the play, early manuscript drafts, original playscripts, playbills, and photographs (including Vivien Leigh’s photograph collection from the shooting of the 1951 film version), as well as posters, lobby cards, first editions of published volumes, and foreign translations. Ten Streetcar items from vaults of The Historic New Orleans Collection follow.

1. The typewriter  Tennessee Williams used this typewriter to write A Streetcar Named Desire, according to its later owner Maria Britneva. (THNOC, 2018.0393)

Tennessee Williams used this typewriter to write A Streetcar Named Desire, according to its later owner Maria Britneva. (THNOC, 2018.0393)

Tennessee Williams gave this typewriter to his close friend Maria Britneva (later Lady St. Just) in 1951. According to St. Just, this is the typewriter on which he wrote A Streetcar Named Desire. Like most of Williams’s works, Streetcar took years to complete, and some of this work was done in New Orleans in 1946–47, while he lived in an apartment at 632½ Saint Peter Street. Following Williams’s death, in 1983, St. Just assumed the role of Williams’s literary executor.

2. The Poker Night  A 1947 draft typescript is titled The Poker Night, the original title for A Streetcar Named Desire. (THNOC, The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, 2001-10-L.588)

A 1947 draft typescript is titled The Poker Night, the original title for A Streetcar Named Desire. (THNOC, The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, 2001-10-L.588)

As early as January 1947 Williams was referring to a manuscript that he was working on as The Poker Night. He had completed the work almost a year prior, on March 16, 1946. When his literary agent Audrey Wood saw the manuscript she knew she had a hit, but she did not like the title. In her memoir she notes that she thought The Poker Night sounded too much like a Western novel. Before Wood sent the manuscript to be typed by her staff, she crossed out the title The Poker Night and wrote in the more poetic A Streetcar Named Desire.

3. The playwright

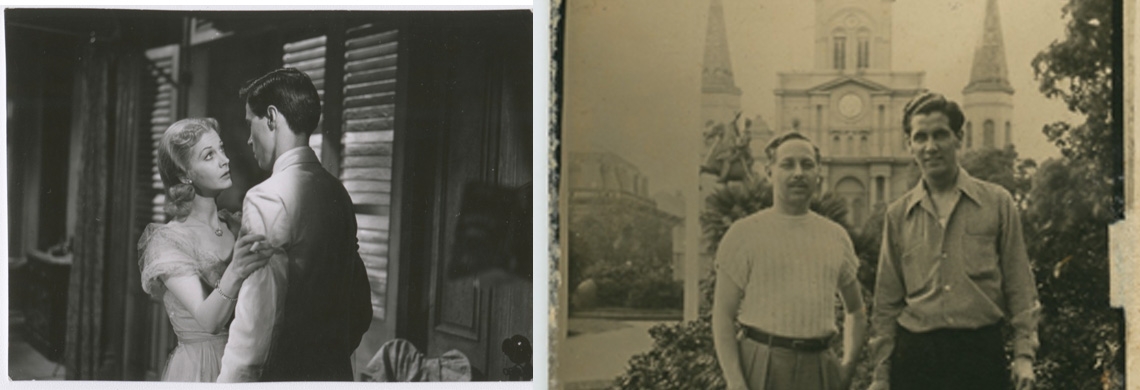

A circa 1945 image shows Williams with his lover and companion Pancho Rodriguez y Gonzales. (THNOC, 2003.0228.1.1)

A circa 1945 image shows Williams with his lover and companion Pancho Rodriguez y Gonzales. (THNOC, 2003.0228.1.1)

Williams’s lover and companion during this period was New Orleanian Pancho Rodriguez y Gonzales, who lived with Williams at 632 ½ Saint Peter Street during the writing of Streetcar. His relationship with Williams was troubled and often erupted into violent verbal confrontations. Pancho later accused Williams of purposely pushing his buttons to see how he would react, as if he was studying Pancho’s behavior for inspiration. The intense, passionate tone of Streetcar likely reflects their tumultuous relationship. Some scholars suspect the character of Pablo Gonzales (one of Stanley Kowalski’s poker buddies) is patterned after Pancho, while others see shades of Pancho in Stanley himself.

4. The playbill

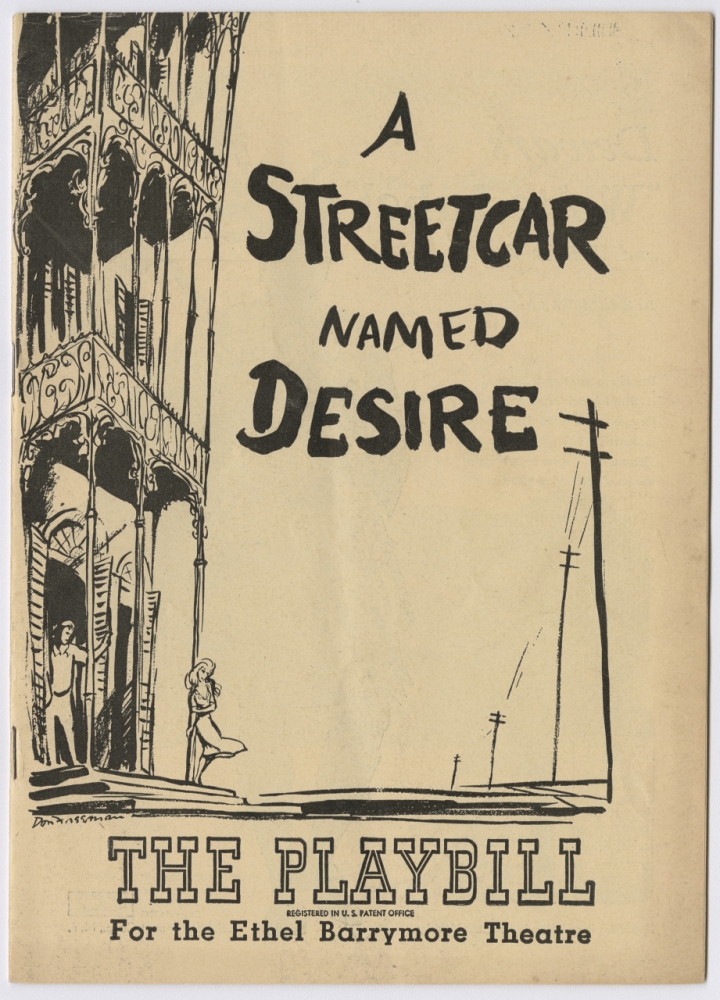

This souvenir program for A Streetcar Named Desire was distributed around the time the played opened on Broadway in December 1947. (THNOC, The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, 2001-10-L.394)

This souvenir program for A Streetcar Named Desire was distributed around the time the played opened on Broadway in December 1947. (THNOC, The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, 2001-10-L.394)

After testing the water in New Haven, Boston, and Philadelphia, A Streetcar Named Desire premiered on Broadway on December 3, 1947, at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre. The response was all that Williams could have hoped for. The show was a hit from opening night on. The production ran for 855 performances and featured a theatrical production dream team that included director Elia Kazan, set designer Jo Mielziner, costumes by Lucinda Ballard, and a jazz score by Alex North.

5. The Brando portrait

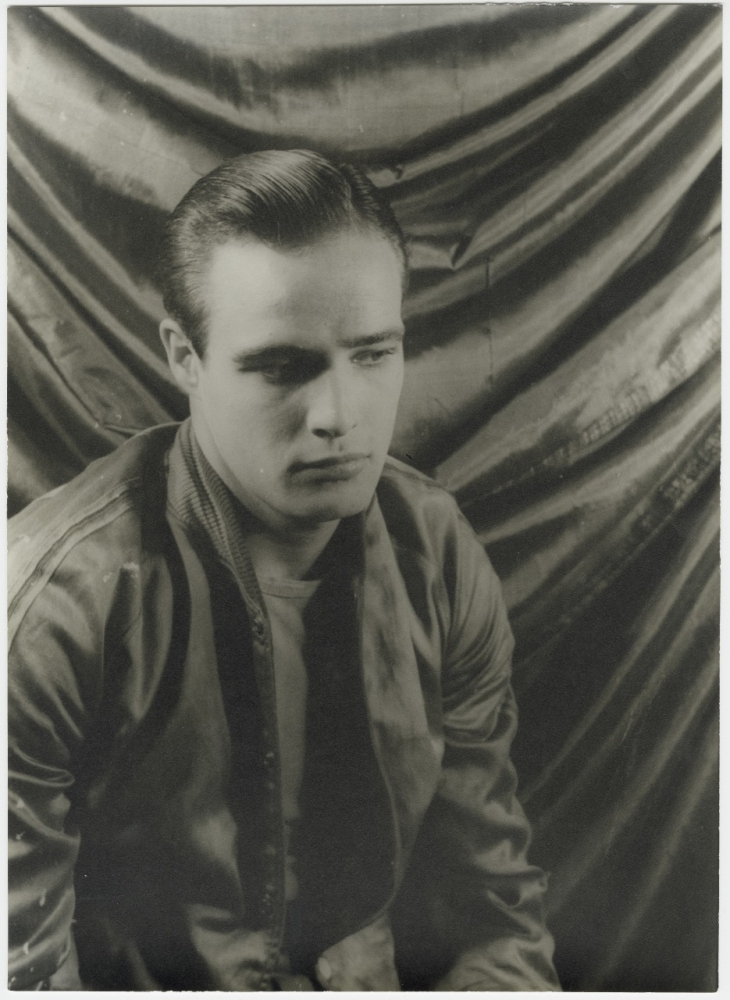

Marlon Brando is shown in A Streetcar Named Desire. (THNOC, 2006.0110)

Marlon Brando’s performance as Stanley Kowalski is one of the most iconic in the history of American theater, but at age 23, he was considered by some to be too young for the role. Brando himself had some reservations, but after being pressed by Kazan he took on the challenge. Kazan gave Brando $20 to travel to Provincetown, Massachusetts, to do a reading for the playwright and get the final OK. Apparently, when Brando arrived, Williams was in the midst of some plumbing issues. Brando fixed the problem, then gave his reading. Williams was enamored. Brando’s presence on stage was overpowering to the point that some of his fellow cast members complained, including Jessica Tandy, the first Blanche. Thankfully, Kazan ignored these complaints and let Brando do his thing.

6. The original Blanche

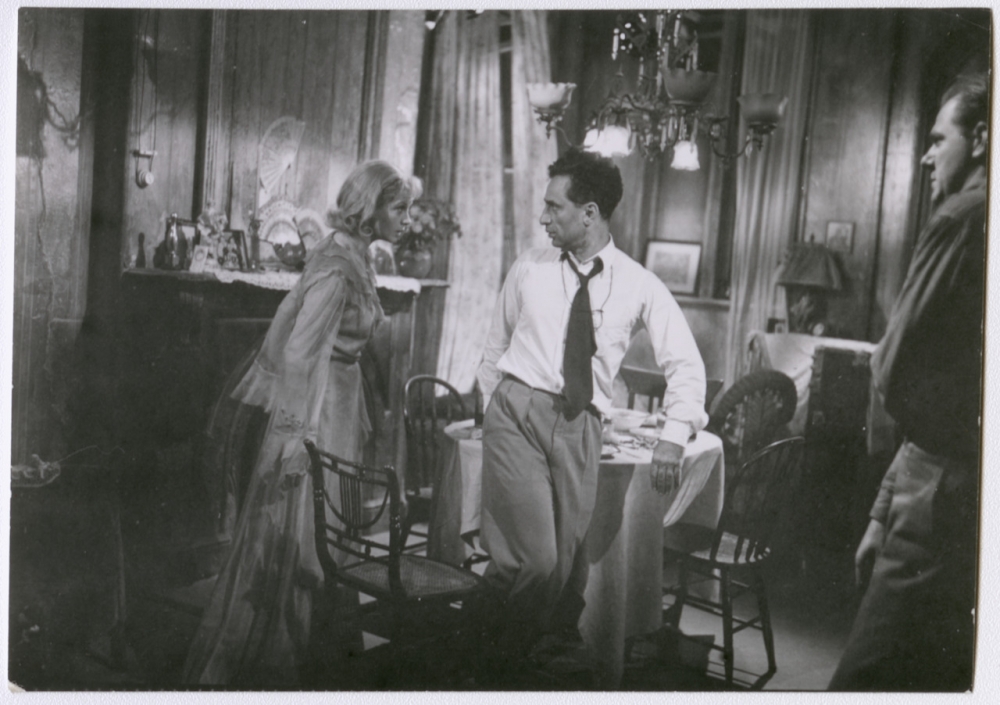

Jessica Tandy is shown performing as Blanche. Tandy was the first to play the role, but she was replaced by Vivien Leigh for the film adaptation. (THNOC, 2002-62-L.1)

Jessica Tandy is shown performing as Blanche. Tandy was the first to play the role, but she was replaced by Vivien Leigh for the film adaptation. (THNOC, 2002-62-L.1)

The character of Blanche is one of the most nuanced and challenging roles to play in the American literary canon. Many scholars believe that the best portrayal came from the first person to perform the role: Jessica Tandy. Tandy impressed Williams, Kazan, and Irene Selznick with her performance in Williams’s one-act play Portrait of a Madonna. Her interpretation of the complicated Blanche brought a fragility and dignity to the role that engendered pity for the manipulative, self-interested aspects of the character. Her performance, which went on for over a year and half, was critically acclaimed and influenced future interpreters from Vivien Leigh to Ann-Margret to Jessica Lange. Tandy was sadly overlooked when three of her fellow cast members were included in the cast of the 1951 film version.

7. The director

An image from Vivien Leigh’s personal photo album shows director Elia Kazan instructing Leigh on the set of A Streetcar Named Desire. (The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, 2001-10-L.1564)

An image from Vivien Leigh’s personal photo album shows director Elia Kazan instructing Leigh on the set of A Streetcar Named Desire. (The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, 2001-10-L.1564)

Williams considered Kazan the best director to interpret his work on stage and film. In a 1947 interview for Cue magazine, Williams said that Kazan was the “one-man theatre that brought Streetcar before the widest audience possible.” Kazan’s realism and his ability to draw emotion from actors fulfilled Williams’s expectations for Streetcar. In a letter from New Orleans to Kazan dated April 19, 1947, Williams writes of Streetcar: “There are no ‘good’ or ‘bad’ people. Some are a little better or a little worse, but all are activated more by misunderstanding than malice. A blindness to what is going on in each other’s hearts.”

This rare image comes from a collection of photographs owned by Vivien Leigh, taken during filming. The photographs may have been given to Leigh for her to choose acceptable promotional images for the film, or they may have been given to her as a memento of her experience.

8. The lobby card

A lobby card shows Marlon Brando seated at a poker table, shouting, in A Streetcar Named Desire. (The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, 2001-10-L.2267)

A lobby card shows Marlon Brando seated at a poker table, shouting, in A Streetcar Named Desire. (The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, 2001-10-L.2267)

The film rights to A Streetcar Named Desire were purchased by Charles K. Feldman Productions; filming took place in the summer and fall of 1950. Most of the Broadway cast was secured for the film, as well as director Elia Kazan. Tennessee Williams was invited to help screenwriter Oscar Saul adapt the playscript to a workable screenplay. The most problematic part of the adaptation was getting around the script changes demanded by Hollywood’s Production Code Administration. Some of the more significant changes demanded by the Code centered on the play’s controversial rape scene. Masterful direction by Kazan and some wordcraft by Williams and Saul made the film a success despite these changes.

9. The leading lady

Vivien Leigh is pictured on the set of A Streetcar Named Desire. Her casting as Blanche was not Kazan’s choice but a studio decision inspired by Leigh’s performance in Gone with the Wind. (THNOC, The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, 2001-10-L.1377)

Vivien Leigh is pictured on the set of A Streetcar Named Desire. Her casting as Blanche was not Kazan’s choice but a studio decision inspired by Leigh’s performance in Gone with the Wind. (THNOC, The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, 2001-10-L.1377)

Vivien Leigh was not Kazan’s choice for Blanche: her casting was a decision forced on him by the studio. Leigh was a box office draw after the success of Gone With the Wind (1939) and was familiar with the role, having starred as Blanche in the British stage production directed by her husband, Laurence Olivier. Kazan was worried that she would not be able to adapt to his complex vision of Blanche, who engages in a difficult balancing act with Stanley. In a letter to Kazan written from New Orleans on April 19, 1947, Williams described Streetcar as “a tragedy with the classic aim of producing a katharsis of pity and terror, and in order to do that Blanche must finally have the understanding and compassion of the audience. This without creating a black-dyed villain in Stanley. It is a thing (misunderstanding) not a person (Stanley) that destroys her in the end. In the end you should feel—‘If only they all had known about each other!’”

10. The global reach

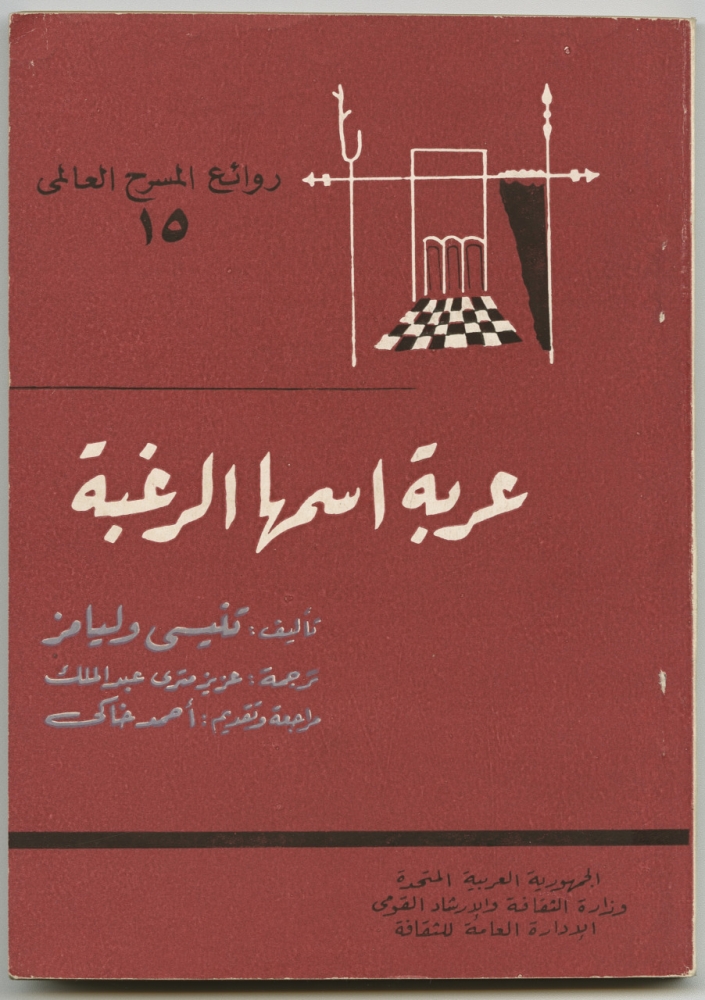

This edition of A Streetcar Named Desire, in Arabic, shows the reach of the play to a worldwide audience. (THNOC, The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, Arabic Edition 2001-10-L, item 3708)

This edition of A Streetcar Named Desire, in Arabic, shows the reach of the play to a worldwide audience. (THNOC, The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, Arabic Edition 2001-10-L, item 3708)

Streetcar was quickly translated and adapted for non-US audiences, and its universal themes immediately resonated with readers and viewers throughout the world. Within two years of the Broadway premiere, major productions were staged in Havana; Mexico City; Rome (by noted stage and film director Luchino Visconti); Gothenburg, Sweden (by Ingmar Bergman); London (by Laurence Olivier); and Paris (by poet, visual artist, and director Jean Cocteau). The 1951 film version was released worldwide, reaching audiences of all social classes. The film defined and continues to shape popular perceptions of New Orleans around the world.