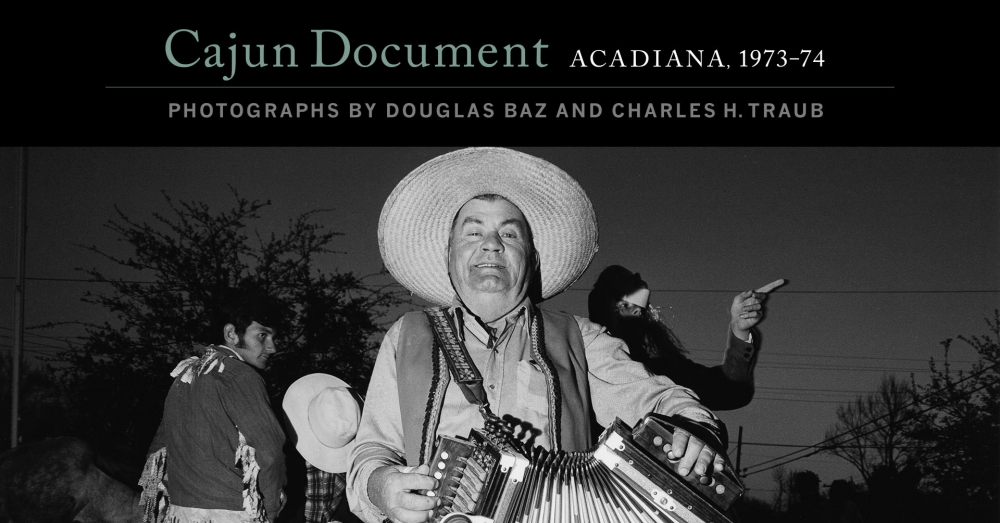

In conjunction with The Historic New Orleans Collection’s book and exhibition Cajun Document: Acadiana, 1973–74, our visitor services staff delved into the stories behind south Louisiana’s delicious cuisine.

Local dishes in south Louisiana are often described as being either Cajun or Creole. Yet, determining whether a particular meal is one or the other is not so straightforward because these identities have complex and overlapping histories. Many people use geography to differentiate between the two, connecting Cajun food to the rural prairies and bayou regions of south Louisiana and Creole food to New Orleans.

By this definition, there exists much overlap between the two cuisines. Gumbo, jambalaya, crawfish bisque, and pralines could certainly be found on both menus. Certain dishes, like bananas foster, or shrimp remoulade, are traditionally associated with New Orleans Creole cooking, while others such as couche-couche and macque choux (pronounced küsh-KÜSH and mäk SHÜ) are found in the Acadian parishes. At the same time, Creole is not synonymous with New Orleans, nor Cajun with rural areas. Many people, especially people of African descent, in rural south Louisiana, also identify as Creole. These rural Creoles would tend to identify more with the foods that are considered Cajun.

Three teenagers are pictured in front of a seafood sign in Carencro, Louisiana, in 1973 or '74. (Photograph by Douglas Baz and Charles H. Traub, THNOC, 2019.0362.118.1)

If one does accept the rural vs. urban definition, there are a few general differences between the two. Cajun cooking tends to consist more of one pot meals, whereas Creole cooking is more likely to use multiple pots and sauces. Cajun cuisine often uses more generous amounts of spice than its Creole counterpart, while Creole dishes are more likely to feature tomatoes as an ingredient.

With the popularization of Louisiana foods across the nation, the boundary between Cajun and Creole cuisine has become less distinct. Yet, many Louisiana cooks identify as either Cajun or Creole, designating their dishes with the same label. So, if you are ever unsure what you are eating, perhaps the best way to find out is to simply ask the cook!

1. A dish from the 18th century

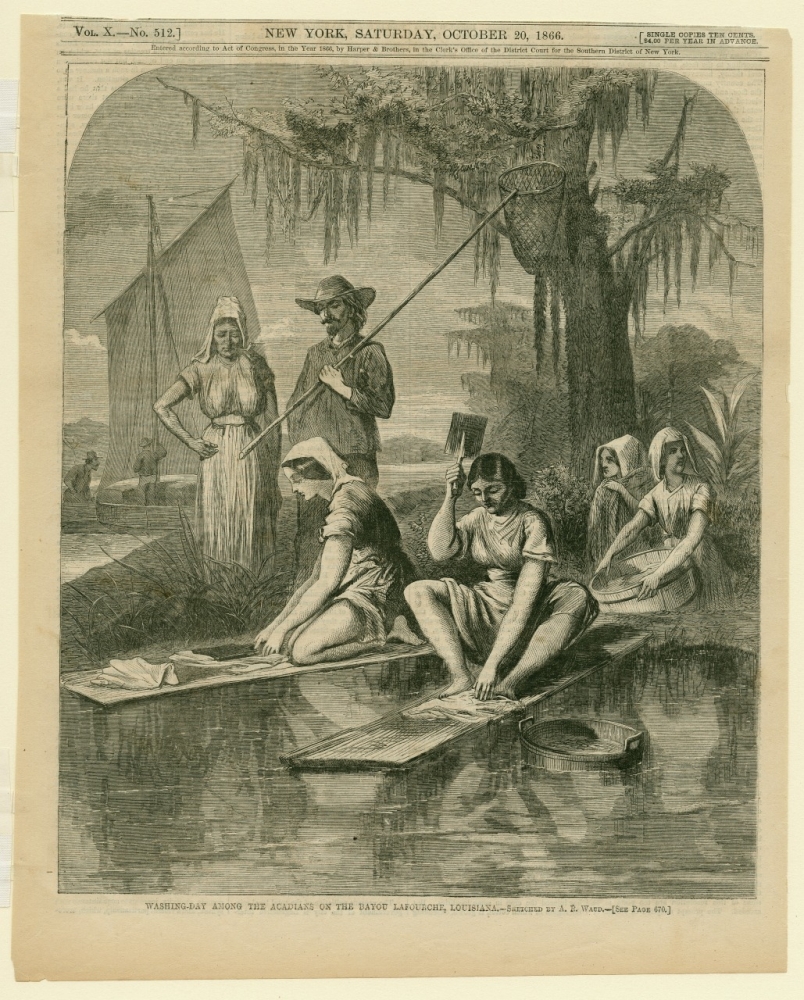

In the transition from Acadian to Cajun, culinary habits and preferences shifted to fit a different environment, incorporating new cultural influences along the way. Over time, the Cajun diet came to bear little resemblance to that of the 18th-century Acadians in Nova Scotia. One dish, however, did survive Le Grand Dérangement and the subsequent two and a half centuries in Louisiana—fricot (pronounced free-KOH). Believed to have its origins in France, this versatile potato and dumpling stew is still prepared in lower Lafourche Parish. Like gumbo, fricot can take on many different iterations.

Fricot is still made in lower Lafourche Parish. This mid 19th-century illustration depicts Acadians doing laundry along Bayou Lafourche. (THNOC, 1974.25.31.209)

In Canada’s Maritime Provinces, it could be made with chicken, pork, beef, fish, duck, or even rabbit or clams. In lower Lafourche, the stew’s base is created by searing potatoes in vegetable oil, then deglazing the pan with water until the starches from the potato produce a thick, rich sauce. In recent years, some Cajun cooks, inspired by their Acadian cousins, have developed their own versions of fricot. Lucius Fontenot of Lafayette discovered the stew when he visited Nova Scotia. Upon his return to Louisiana, Fontenot made fricot with a distinctly Cajun twist, adding smoked sausage, tasso ham, and cayenne pepper.

2. From corn to rice

Rice is well known as a staple in south Louisiana cuisine, featured in dishes like gumbo, rice dressing (also known as “dirty rice”), and boudin. However, this was not always the case. Until the early 20th century, corn, not rice, served as the predominant starch in the Cajun and Creole diet. A typical meal in 19th-century Acadiana would have consisted of slow-cooked meat, often salt pork, served with cornbread and whatever vegetables were in season. For breakfast, couche-couche, a dish of fried corn was often served, and sweet corn was often prepared in macque choux, a dish with Native American roots.

A 1952 film reel shows rice production and a festival in Acadia Parish, Louisiana. (THNOC, gift of Terry Flettrich Rohe, 2011.0238.3)

Rice was sometimes grown, but the success of this so-called “providence rice,” sown in low-lying areas, was entirely dependent upon rainfall. Beginning in the late 19th century, immigrants from the Midwest introduced steam-powered irrigation into the prairies of southwest Louisiana, allowing for the large-scale cultivation of rice. It continues to be grown in the region today. By the 1920s, rice had largely supplanted corn, and it remains a part of many favorite regional dishes.

3. Coffee

The smell of brewing coffee is familiar in many places throughout the world. Louisianians have long practiced their own traditions in the preparation and serving of the beverage. Traditionally, coffee was an ever-present part of Cajun and Creole social occasions and serving the delicacy to guests in the finest vessels the household had to offer was a mark of pride in their hospitality.

Coffee remains a staple in south Louisiana homes. This image, which shows instant coffee on the table, was taken in 1973 or '74. (Photograph by Douglas Baz and Charles H. Traub, THNOC, 2019.0362.61.1)

Coffee found its way to Louisiana quickly. French custom and a relative lack of access to tea cemented its position in the colony. Limitations in transportation technology kept coffee in the realm of expensive luxury until, roughly, the Great Depression. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, New Orleans grew into a major coffee importation hub.

Coffee’s time as a luxury item fixed its status in Louisiana, and its service by Cajuns as “high coffee” took on a formality and grandeur as time went on. It was not uncommon for the entire household to get involved in serving guests the beverage. The lady of the house would carefully brew the coffee in gregues, porcelain coated metal pots. Children would then serve the coffee before being told to go outside while the adults chatted. To refuse a cup was considered extremely gauche.

4. Gigging for frogs

In depression-era Louisiana, frog gigging, the practice of hunting frogs with a gig or multi-pronged spear, became a source of supplemental income for south Louisiana. Bullfrogs, or ouaouarons (pronounced wä-wä-RÜNS) in Louisiana French, could be transported quickly to restaurant tables in New Orleans via rail when their harvest became financially lucrative. The coauthors of Stir the Pot: The History of Cajun Cuisine explain that “[i]n 1932...frog exports rose to 163,000 in a six-month period. Virtual armies of impoverished yeoman farmers, sharecroppers, and school children harvested these enormous quantities of bullfrogs.”

The Acadia Parish town of Rayne became known as the “Frog Capital of the World” for the number of frogs it exported to New Orleans in oak barrels. The industry began in the 1880s when local chef Donat Pucheu began selling frogs to New Orleans restaurants. Today, Rayne’s annual Frog Festival features frog racing and jumping, and there are no possession limits to the number of bullfrogs one can harvest in Louisiana. Frogs are usually caught after dark through sight and sound—their yellow eyes throwing off a glow when scanned with a flashlight. Frog legs are still found on many restaurant menus throughout New Orleans.

5. The advance of seafood inland

Today, all kinds of seafood dishes are part of the Cajun and Creole culinary repertoire. While eating fish, mostly freshwater varieties, was common in the region during the Lenten season, prior to the mid-20th century, seafood consumption was limited to those areas where saltwater fish, crabs, and shrimp could be caught and consumed immediately. This changed with developments in refrigeration and Louisiana’s transportation system. By WWI, ice manufactured in factories had replaced the “frozen water trade” in ice shipped from New England to local ice houses. Residents could purchase ice to keep perishable food cool in their home ice boxes, which became common in Louisiana just before Huey P. Long was elected governor in 1928.

Oystermen work aboard a boat in 1973 or '74. Refrigeration and transportation improvements made it easier for fishermen to sell their catch further from the coastline. (Photograph by Douglas Baz and Charles H. Traub, THNOC, 2019.0362.63)

When the stock market crashed in 1929, Governor Long hired over 20,000 men to build and expand bridges and roads across Louisiana. This unprecedented highway infrastructure program helped spawn Louisiana’s commercial fishing industry by allowing fishermen to quickly transport their harvests to expanded markets. With further developments in commercial and residential refrigeration and increased social mobility in the post-WWII period, more Acadiana residents could access, preserve, and enjoy seafood. Cajuns in places like Lafayette began adding seafood to their gumbos and étouffées (pronounced AY-tü-FAY), while restaurants provided a variety of fried seafood dishes on their menus.

6. The coming of crawfish

It might surprise you to learn that boiled crawfish, a popular dish in south Louisiana, is a modern-day tradition that has its origins in the mid-20th century. Indigenous people were eating the crustaceans long before the Acadians arrived in the Louisiana colony; however, the newcomers did not partake. Customarily, Acadians used them for bait, not as something to put on the table. By the 1880s there is mention of people eating crawfish during Lent, but it was considered a poor man’s food. During the 1950s eating boiled crawfish slowly began to catch on. Restaurants in Breaux Bridge were the first to offer crawfish on their menus, particularly crawfish étouffée, and the city became known for farming and cooking the crustacean.

A giant crawfish, dubbed Monsieur L'Écrevisse, floats down Bayou Teche during the Breaux Bridge Crawfish Festival in 1973 or '74. (Photograph by Douglas Baz and Charles H. Traub, THNOC, 2019.0362.33)

Governor Earl K. Long signed the Louisiana legislature’s resolution designating Breaux Bridge the “Crawfish Capital” in 1959. The following year the first Crawfish Festival took place, and subsequently boils became popular. The crustaceans are cooked in highly seasoned water that includes onions, garlic, celery, and ample amounts of cayenne. Traditionally, corn on the cob and potatoes are thrown in to soak up the seasoning and enhance the meal. Today’s cooks experiment with other additions, including mushrooms, artichokes, brussel sprouts, and asparagus. Peppery sweet chunks of pineapple make for a delicious surprise. What do you like to add to your boil?

7. South Louisiana’s signature dish

Philadelphia has its cheese steak and Montreal has its poutine, but in south Louisiana, boudin (pronounced bü-DAN) is the signature dish. This ubiquitous sausage, traditionally made with a rice and pork dressing encased in pig intestines, is sold in restaurants, grocery stores, gas stations, and community bazaars throughout Acadiana. Boudin (from which it is believed the English word “pudding” is derived) is usually prepared in Louisiana as boudin blanc—pork liver, rice, green onion, seasonings—or boudin noir, containing pork blood for added flavor.

A Mardi Gras reveler hangs a link of boudin out the window of her car in this image from 1973 or '74. (Photograph by Douglas Baz and Charles H. Traub, THNOC, 2019.0362.78.1)

Boudin has recently seen increased attention due to the launching of the “Cajun Boudin Trail” and the publication of Boudin: A Guide to Louisiana’s Extraordinary Link by UL–Lafayette Press, the first book on the subject. Louisiana has no shortage of culinary capitals and the small town of Scott, just four miles from Lafayette, is no exception. It is home to more boudin sellers than any place in the state and has been dubbed the “Boudin Capital of the World” by the state legislature.

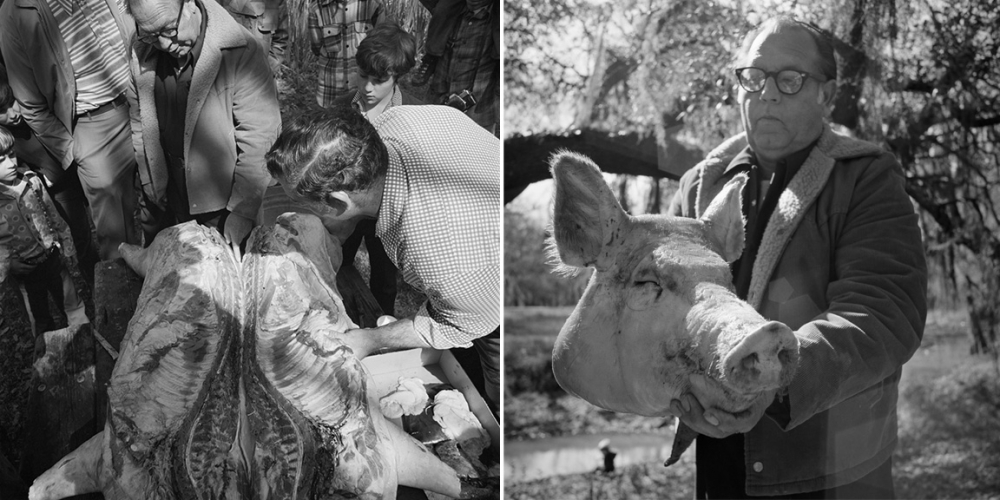

8. An all-day hog killing

In fall in south Louisiana, a handful of families continue to gather for an age-old community affair, complete with distinctive participant roles and the transmission of intergenerational knowledge. This gathering—called melodiously in French, la boucherie (pronounced lä BÜ-sher-REE)—is a hog-killing. Harking back to decades past when refrigeration was nonexistent and it was necessary to quickly butcher and prepare meat for the winter, a boucherie is a communal endeavor where everyone works and everyone shares in the seemingly endless number of dishes prepared using every part of a large pig.

Photographers Douglas Baz and Charles H. Traub captured these scenes at a Boucherie during their visit to Louisiana in 1973 or '74. (THNOC, 2019.0362.3.3 and 2019.0362.3.4)

The day’s work commences with administering a single gunshot to the head of a hog, followed by the bleeding, scraping, and disemboweling of the animal. Working quickly to avoid spoilage, the various parts of the hog are prepared to make sausages, including the famed boudin, along with grattons (cracklings), fromage de cochon (hogshead cheese), and fraisseurs (organ meat stew). The recipes for preparing these items are often jealously guarded and are passed down orally and by observation. Traditionally, men undertake the cooking outdoors, while women prepare dishes in the kitchen. After the work is done, participants share a meal. A boucherie combines work and play, reinforces communal bonds, and keeps alive a conscious collective memory of days gone-by in the bayous and prairies of south Louisiana.

9. The popularization of south Louisiana cuisine...

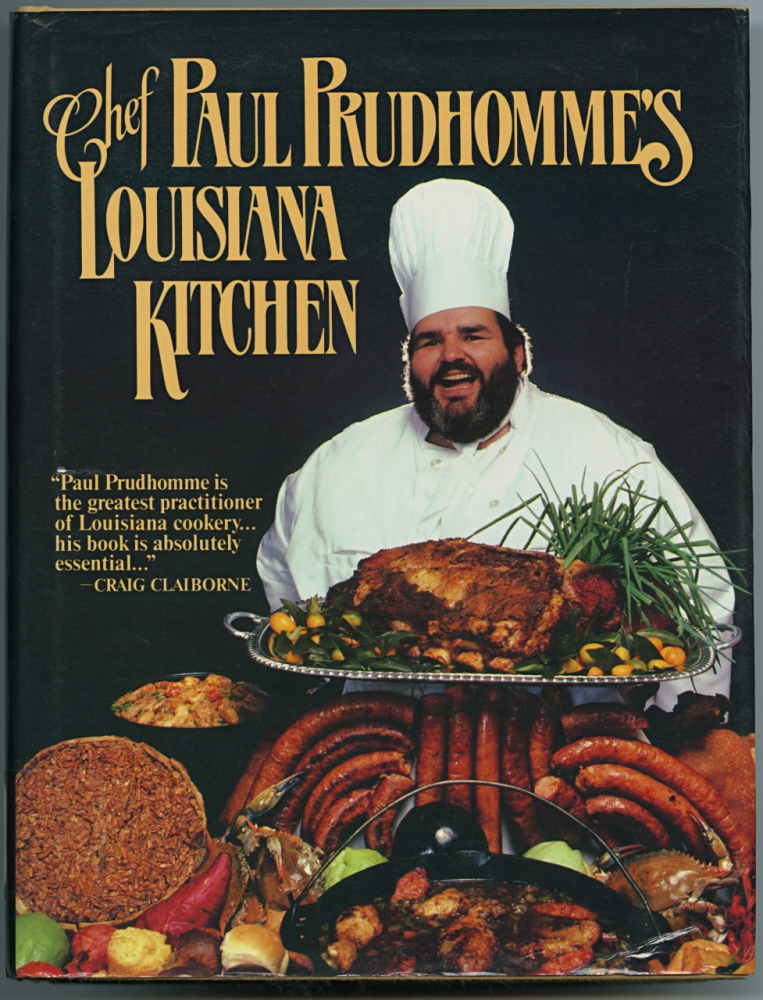

From cooking at his mother’s elbow as a boy in Opelousas, Louisiana, Paul Prudhomme became an internationally known chef who not only refashioned the approach to Cajun cooking but also popularized it. Encouraged by Ella Brennan, who hired him as the first American-born chef at Commander’s Palace, Prudhomme creatively blended the rural Cajun style of food preparation with New Orleans’ French Creole sauce-based dishes. He insisted that ingredients always be fresh and locally produced. For example, rather than serving the expected trout almondine he declared, “We don’t have almonds in Louisiana. Let’s use pecans.”

Chef Paul Prudhomme’s Louisiana Kitchen offered home cooks the chance to prepare the same types of dishes that he was serving at his famed New Orleans restaurant. (THNOC, 84-205-RL)

In 1979, Prudhomme opened his own restaurant, K-Paul’s, to much acclaim. In the 1980s, he brought Louisiana foodways to national prominence through culinary tours, bestseller cookbooks, television shows, and a line of spice blends. Prudhomme shared his expertise freely with a number of young chefs who flourished under his tutelage, particularly Emeril Lagasse who continues his legacy of fusion cuisine based on the freshest ingredients.

10. ...and the spinoffs.

Cajun fries, Cajun pizza, Cajun sushi, oh my! Since its rise to national prominence in the 1980s, many non-Louisianians perceive “Cajun food” to mean anything spicy and often blackened—thanks to the success of Chef Paul Prudhomme’s blackened redfish dish. Even within the state one can find so-called Cajun restaurants serving food of dubious Louisiana origin to unwitting visitors. While it is easy to joke about Cajun McChicken sandwiches (yes, this was a real thing), there are more serious innovations that exemplify the delicious results of cross-cultural exchange and adaptation.

Take, for example, Viet-Cajun Crawfish in Houston, Texas. Vietnamese immigrants who settled in Louisiana in the wake of the Vietnam War found Cajun crawfish boils to be reminiscent of outdoor seafood establishments in their home country. When Vietnamese Louisianians moved to Houston they brought the tradition of crawfish boils with them. Vietnamese-owned restaurants, serving Cajun-style boiled crawfish, became especially popular in Houston with the arrival of Vietnamese families from New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Over time, Vietnamese chefs began fusing Cajun and Vietnamese flavors in their crawfish preparation. This Houston invention has made its way back to Louisiana and as far as California. Much like the Acadians adapted to changing environments and cultural influences in the process of making Louisiana their home, so have Vietnamese immigrants, who found something familiar in Cajun crawfish boils and added their own twist.