Editor’s note: This story is released in conjunction with The Historic New Orleans Collection’s 2021 Symposium, “Recovered Voices: Black Activism in New Orleans from Reconstruction to the Present Day.” The interactive website includes books, stories, videos, and a March 5–7 program. Learn more here.

On Monday morning, July 30, 1866, Lucien Capla, a shoemaker, and his young son Arnold made their way to the Mechanics’ Institute—less than a block off Canal Street, in the heart of the city’s business district. Lucien brought Arnold with him to witness history: a constitutional convention, called to secure voting rights for Louisiana’s Black citizenry.

Lucien’s father had fought in the Battle of New Orleans. He himself had served in the US Army Native Guard, in the Civil War. Perhaps his son might grow up in a world where Black patriots enjoyed the same civil rights as their white peers.

Lucien’s father had fought in the Battle of New Orleans. He himself had served in the US Army Native Guard, in the Civil War. Perhaps his son might grow up in a world where Black patriots enjoyed the same civil rights as their white peers.

Then gunshots rang out. I saw policemen firing, and shooting the Black people, Lucien would recall. They were shooting poor laboring men, men with their tin buckets in their hands, and even old men walking with sticks. The shots continued, unceasing. “For God’s sake, don’t shoot us!” the conventiongoers prayed, but the police tramped upon them, and mashed their heads with their boots, and shot them after they were down.

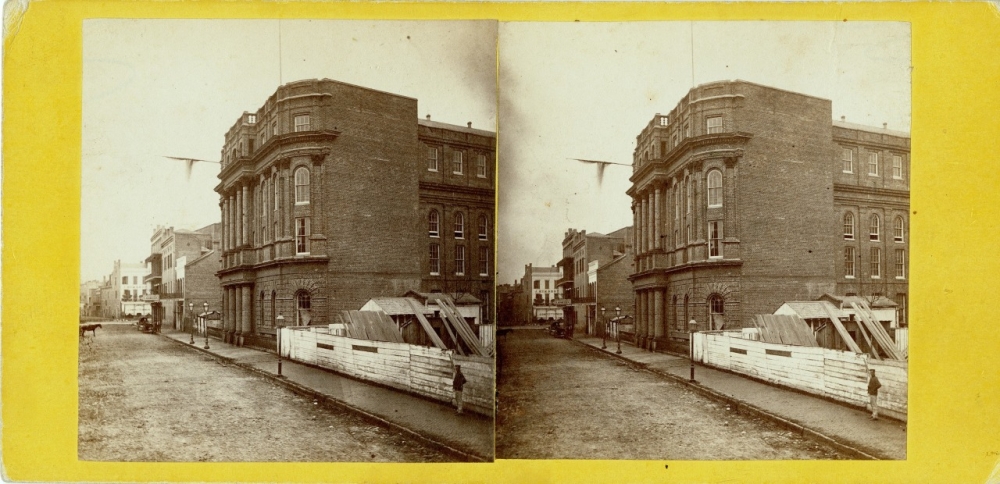

The Mechanics’ Institute is shown here around 1870. The building was torn down in 1908 and replaced with the Grunewald Hotel (now the Roosevelt). (THNOC, 1988.134.19)

The Mechanics’ Institute is shown here around 1870. The building was torn down in 1908 and replaced with the Grunewald Hotel (now the Roosevelt). (THNOC, 1988.134.19)

Lucien barely escaped with his life. Arnold, not yet nine years old, was stabbed three times and took four bullets to the head. He lost an eye.

In New Orleans, some newspapers called it a riot. But there’s more than one way to tell a story.

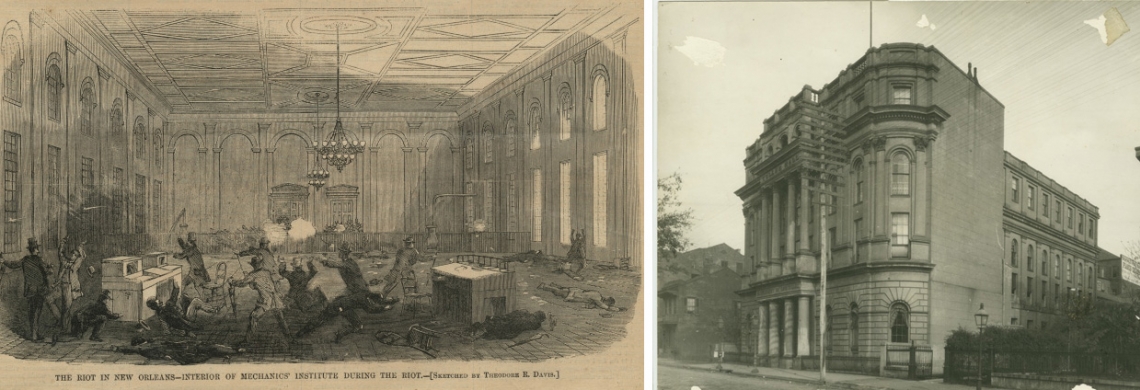

A Harper’s Weekly illustration shows the chaotic scene inside the building as members of the white mob murder Black people at the Mechanics’ Institute. (THNOC, 1979.200 iii)

A Harper’s Weekly illustration shows the chaotic scene inside the building as members of the white mob murder Black people at the Mechanics’ Institute. (THNOC, 1979.200 iii)

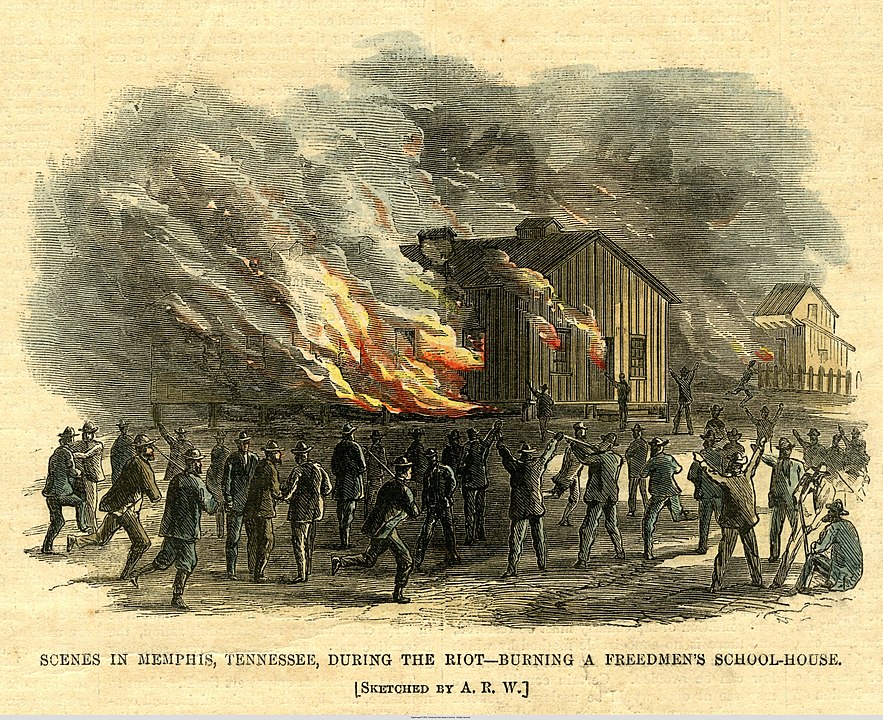

A congressional delegation traveled to New Orleans to interview Lucien Capla and nearly 200 others. Coupled with news of a recent massacre in Memphis, the events at the Mechanics’ Institute convinced Northerners of the folly of President Andrew Johnson’s policy of rapprochement with ex-Confederates. Radical Republicans swept into office in the November 1866 midterm elections. By early 1867, Congress had passed the first of its Reconstruction Acts, carving the South into military districts. Ratification of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments—granting Black men citizenship and suffrage—followed in 1868 and 1870. The Radical agenda, ascendant in Congress, sanctified the blood spilled on New Orleans streets.

A massacre of Black people in Memphis earlier in 1866, coupled with the Mechanics’ Institute massacre, convinced Northerners to enact tougher policy against former Confederates in the South. (Courtesy of Tennessee State Library and Archives)

This year, The Historic New Orleans Collection celebrates three new books, each centering on Black activism during Reconstruction. Plotting the launch of these titles, we weighed the pros and cons of publishing three overlapping narratives. Would readers weary of the subject matter or welcome the synergy? Economy Hall, Afro-Creole Poetry in French, and Monumental all linger over the Mechanics’ Institute massacre, yet each mines the incident for different meaning. The distinctiveness of each book’s approach, and the exigencies of our present historical moment, reinforce the value of retelling history—over, and over, and over.

* * *

Fatima Shaik grew up in the Seventh Ward of New Orleans, imbibing her community’s history through the stories told by Creole family and friends. But it wasn’t until 1997, when she read Caryn Cossé Bell’s Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Tradition in Louisiana that she first heard of the Mechanics’ Institute massacre. Decades earlier, her father had rescued 24 journals belonging to the Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle from a trash hauler’s pickup truck. Now Shaik—a journalist and professor of communications—began a systematic review of the society records, the earliest dating to 1836. Some of the names in the journals also appeared in Bell’s book, so she created a spreadsheet to cross-reference the Economie members against Bell’s reportage. Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood, began to take form.

For the next decade and a half, Shaik pored over the Economie journals, translating the handwritten records from their original French. To deepen her understanding of the massacre, she visited a library that held the 1867 Report of the Select Committee on the New Orleans Riots. Securing a copy of the 600-page report, she pored over its pages.

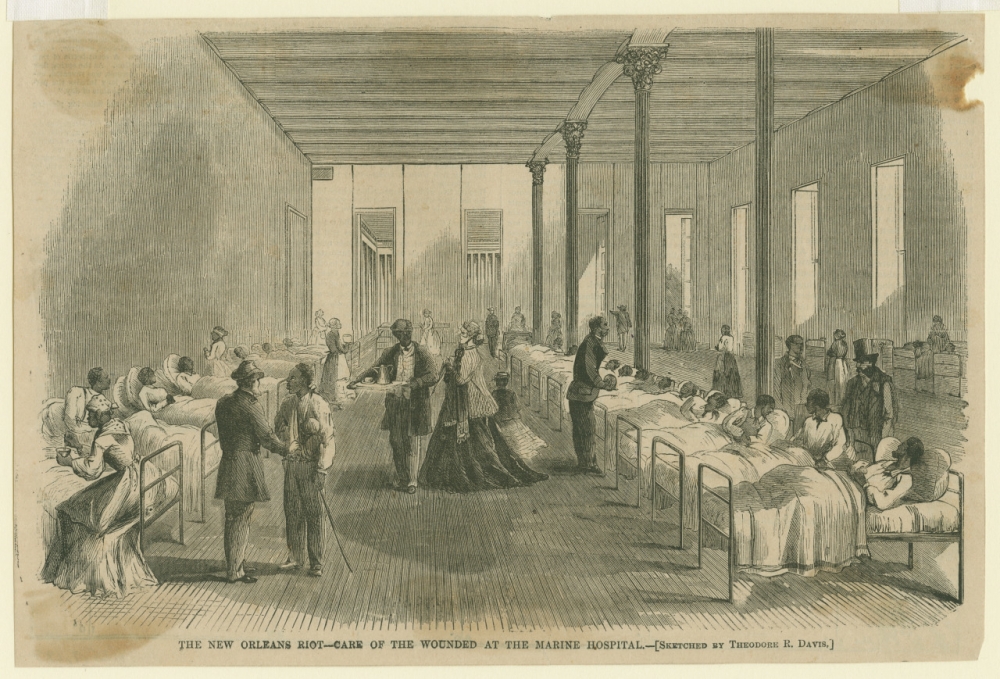

An illustration shows Black patients who were wounded in the massacre. Witness testimony resulted in a 600-page report. (THNOC, 1974.25.9.197)

An illustration shows Black patients who were wounded in the massacre. Witness testimony resulted in a 600-page report. (THNOC, 1974.25.9.197)

And then, drawing from the congressional testimony and countless other primary sources—newspapers, real estate records, court cases, oral histories—Shaik set out to describe the events of July 30, 1866, from the perspective of those who were attacked. Ludger Boguille, the longtime secretary of the Economie, “left home that morning, walking over sidewalks strewn with the golden undersides of magnolia leaves and beneath conclaves of oak trees knotted together by Spanish moss. He passed brown-skinned vendors, workingmen who were pink and sweating under the midsummer sun, people of all colors chatting, while others turned away or gave sidelong looks.” Boguille entered the hall but drifted back outside when the morning’s speeches were postponed. When the shooting began, he could have fled—but instead, he reentered the building. The slaughter defied the laws of God and man.

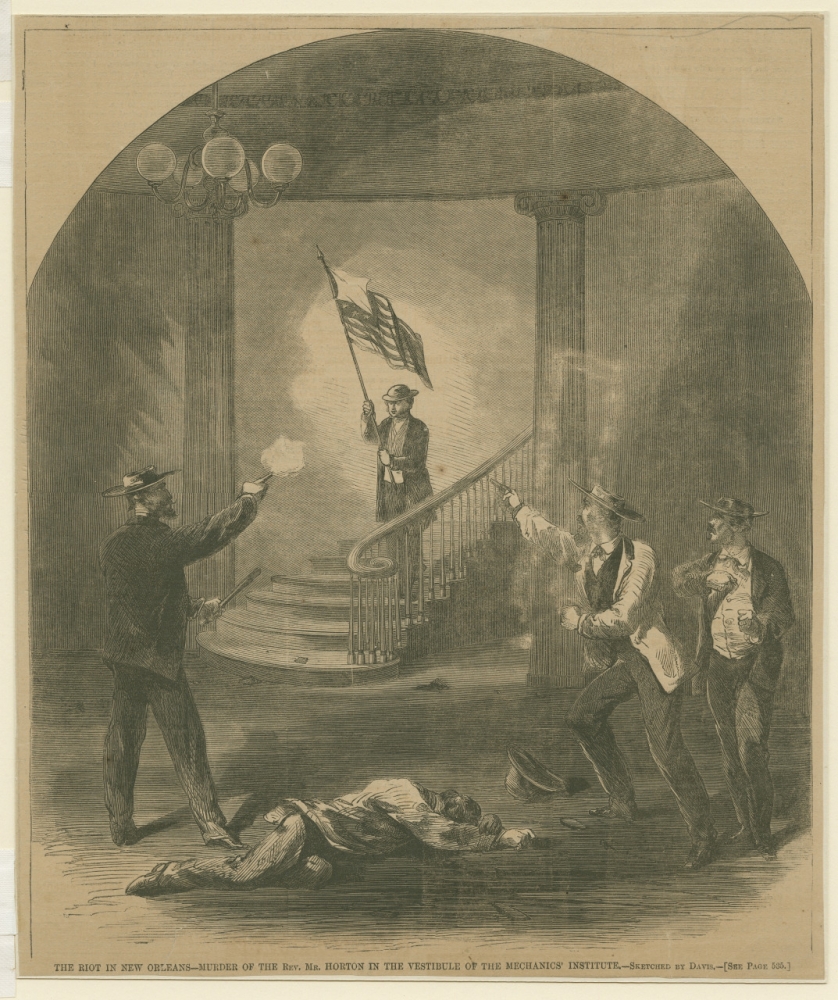

One victim was a white chaplain who tried to signal surrender by waving a handkerchief on a pole. The chaplain “went as far as the door and was met by a crowd of policemen, 40 or 50 in number, who immediately commenced firing, and there he was shot—about two paces from the door.” Boguille escaped with relatively minor wounds, but only because the mob at the front door was distracted. They had seized the man who exited immediately ahead of Boguille and killed him, instead.

The white chaplain that Ludger Boguille described is depicted in this illustration, waving a white handkerchief affixed to an American flag to signal surrender. He was shot by the mob. (THNOC, 1974.25.9.307)

Six Economie members attended the convention. Five spoke before the congressional committee investigating the atrocities; the sixth, Victor Lacroix, died at the scene. But Lacroix, too, would testify. Three years after the massacre, at a séance attended by members of the Economie brotherhood, Lacroix’s ghost returned. His words are captured in the journals of the Cercle Harmonique, now archived at the University of New Orleans. “Patience, because your recompense is on its way,” the spirit said. “You will be paid for your suffering.”

This Harper’s Weekly illustration shows a commission of four white men questioning a Black witness following the Mechanics’ Institute massacre. Witness testimony provided crucial primary source material for Fatima Shaik’s research into the massacre. (THNOC, 1974.25.9.198)

* * *

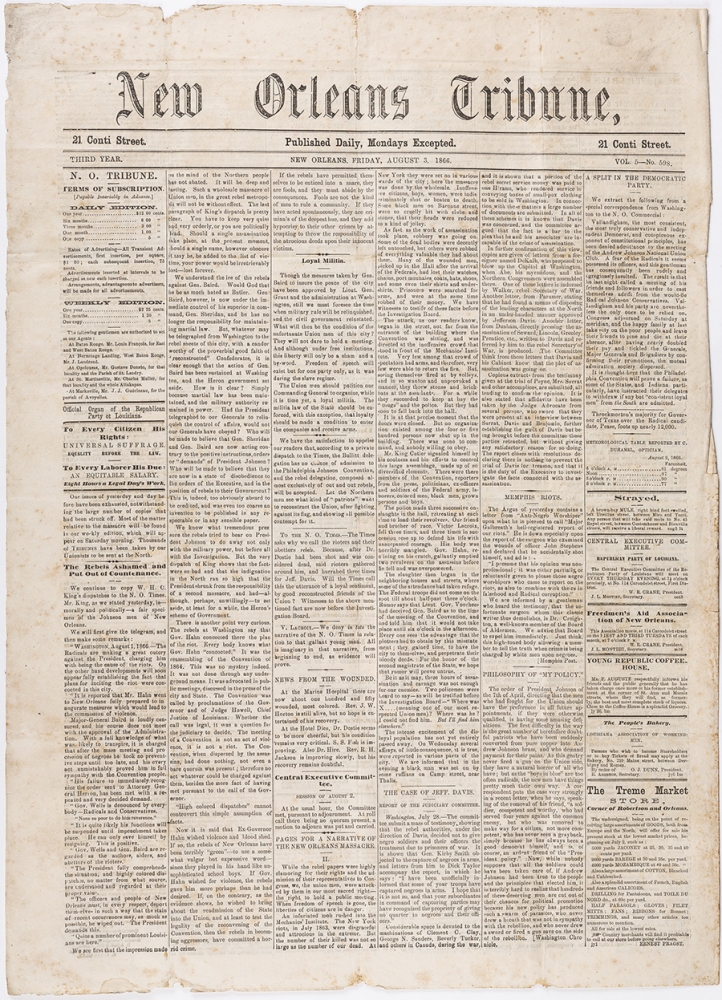

Nearly 1500 miles from New Orleans, and 150 years after the Mechanics’ Institute massacre, Clint Bruce made the discovery of a lifetime: several “missing” issues of La Tribune de la Nouvelle-Orléans, published in the immediate aftermath of the massacre and long assumed lost by scholars. The Tribune, founded in 1864, was America’s first African American daily. These missing issues, this holy grail of eyewitness testimony, had been sitting for decades in the archives of the American Antiquarian Society.

Clint Bruce re-discovered the “missing” issues of the New Orleans Tribune in the archive of the American Antiquarian Society. He is shown here, working with one of the scanned editions on an iPad. (Image courtesy of Clint Bruce)

Clint Bruce re-discovered the “missing” issues of the New Orleans Tribune in the archive of the American Antiquarian Society. He is shown here, working with one of the scanned editions on an iPad. (Image courtesy of Clint Bruce)

Bruce is a professor of literature, sensitive to the nuances—and power—of language. As he writes in Afro-Creole Poetry in French from Louisiana’s Radical Civil War–Era Newspapers, the lost issues show that the Tribune “worked hard to prevent the racist press from controlling the narrative.” Through reportage, editorials, and poetry, the Tribune exposed the falsehood of one dominant storyline in the white papers—that the event had been a Black “riot,” not a white-perpetrated “massacre.”

Three to four dozen men, if not more, lay dead. Close to 150 others had been wounded, the vast majority people of color. The blame, opined the New Orleans Bee, fell fully on the victims: “reckless and unprincipled organizers of sedition and revolution.”

Like Shaik, Bruce didn’t learn of the Mechanics’ Institute massacre as he was growing up, in his case in Shreveport. His awakening came later, as he grew into adulthood and came to understand the pernicious reach of Lost Cause ideology. Now based in Nova Scotia, Bruce has focused one area of his scholarship on the radical politics of popular literature. The poets whose verse appeared in the pages of the Tribune and its predecessor, L’Union, adapted Romantic forms to radical ends. In both Afro-Creole newspapers, the poems shared column space with hard news and political commentary—the interplay modeling, for readers, the multivalence of activism.

This edition of the New Orleans Tribune from August 3, 1866, was thought to be lost by scholars. The issues of the Tribune that appeared in the weeks following the massacre provide crucial counter-commentary to the white newspapers who labeled the event a “riot.”

On August 3, 1866, the Tribune published “Notes pour servir a l’histoire du massacre de la Nouvelle-Orléans” or, in Bruce’s translation, “Notes to Serve in the History of the New Orleans Massacre.” The title of the piece signaled an awareness that America would long be fighting its civil wars—and that history books would become the new battlefields. “When liberty of discussion no longer exists,” the Tribune wrote, “all liberties of the citizen are in danger.”

On the one-year anniversary of the massacre, the Tribune published “Ode aux martyrs” / “Ode to the Martyrs,” the work of an unknown poet using the pseudonym Camille Naudin. Its final stanza read,

Encore quelques vers ! Ne parlez plus de guerre ;

Parlez de Liberté! Blancs et Noirs, si naguère

Vous vous êtes battus, oubliez ! oubliez !

Soyez justes et bons, vous serez pardonnés.

À vous martyrisés cette dernière feuille

Que votre âme là-haut au pied de Dieu l’accueille.

Mais je dirai toujours mulâtres, noirs, blancs,

Victor Lacroix est mort, Jeff Davis est vivant.

Just a few lines to go! Of war speak no more;

But speak of Liberty! Whites and blacks, if heretofore

You fought against one another, forget and move on!

Be good and be fair, and you will receive pardon.

For ye fallen martyrs, this final page I write;

May your soul collect it up yonder, at God’s feet.

But, mulattoes, blacks, whites, this fact I must tell:

Victor Lacroix is dead; Jeff Davis lives still.

Naudin’s words, offered here in translation by Bruce, reminded those assembled for the memorial—as they remind us today—that not a single perpetrator of the massacre was ever convicted or jailed.

* * *

Brian K. Mitchell, author of Monumental: Oscar Dunn and His Radical Fight in Reconstruction Louisiana, grew up consuming comic books. So did Barrington S. Edwards, the book’s illustrator. One of Mitchell’s first jobs, as a kid, was at a comic book store, and he and Edwards both reveled in the Marvel universe.

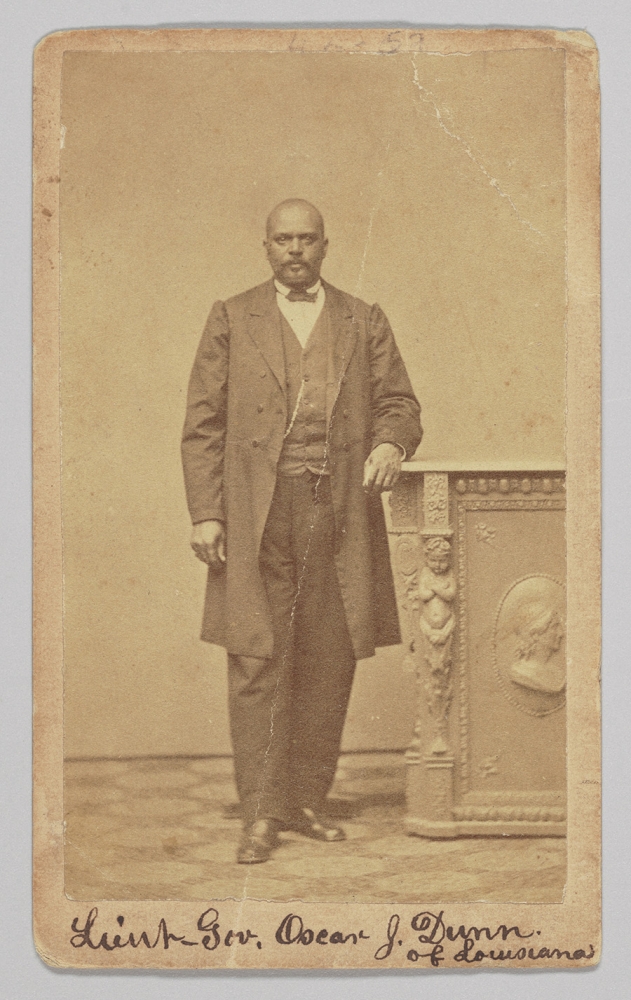

From the start, Mitchell—a descendant of Oscar Dunn’s—knew that he wanted to present his forebear’s story as a graphic history, the better to educate younger audiences about the trailblazing Black politician. But how to handle the trauma and violence of the Reconstruction era?

Oscar Dunn is pictured here sometime after his election as Louisiana’s lieutenant governor in 1868. Dunn was the first Black man to hold the office in American history. (Image courtesy of the National Museum of African American History and Culture)

Mitchell, Edwards, and THNOC editor Nick Weldon decided to confront it “face on.”

Chapter three of Monumental opens with a precis of the political moment: Radical Republicans making waves in Congress, white anger festering in the South, and a new mayor—former Confederate John T. Monroe—seated in New Orleans. A festive panorama introduces the convention scene: flags wave, a marching band plays. And then, abruptly, the massacre.

There’s a phrase, cartoon violence, that conjures overwrought action, underdrawn characters. But Weldon reminds us that every panel in Monumental is meticulously grounded in the historical record. “You go back to the primary source, the congressional testimony, and you almost can’t believe what you’re reading—it’s just so horrific and grotesque,” he says. The Mechanics’ Institute scene “sets the stage” for the political saga that follows, Weldon explains: “We hit it head on, but it never veers into gratuity. There’s bloodshed, there’s menacing, and there’s violence, and this is really what happened—it was messy and ugly and awful . . . but I think there’s enough breath and space in between those scenes of extreme violence that the reader has time to process what’s happening.”

A panel from Monumental shows the slaughter at the Mechanics’ Institute. (Illustration by Barrington S. Edwards)

A panel from Monumental shows the slaughter at the Mechanics’ Institute. (Illustration by Barrington S. Edwards)

Mitchell and Weldon’s script for Monumental was completed in 2019, but the bulk of the book’s illustrations were finalized in 2020—with the final inks, and colors, being laid down as the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd convulsed the nation, and Black Lives Matter activists took to the streets.

“I often try not to read too much or watch too much media while I’m making something,” Edwards says, “but the imagery from the world was pouring in, and I think that played a part in small ways but also in some important ways. Maybe the energy that I held the pen with, or the stroke that I chose on a particular area. After getting done with a composition or rendering an image, I always sit back and reflect on the page that I’ve just illustrated—and aside from the clothing and the costuming, it does feel that this is relevant to right now. The work always feels in conversation with the contemporary.”

Mitchell concurs: “The work we’re doing is important to the times we’re living in.”

Clint Bruce’s commentary is drawn in part from an interview with Laine Kaplan-Levenson, conducted in 2016 for TriPod: New Orleans@300, a podcast jointly produced by WWNO–New Orleans Public Radio, The Historic New Orleans Collection, and the Midlo Center of the University of New Orleans. The complete episode, “An Absolute Massacre: The 1866 Riot at the Mechanics’ Institute,” is available here.

Explore Black activism in New Orleans through our Symposium 2021 website.