Editor’s note: This story is released in conjunction with The Historic New Orleans Collection’s 2021 Symposium, “Recovered Voices: Black Activism in New Orleans from Reconstruction to the Present Day.” The interactive website includes books, stories, videos, and a March 5–7 program. Learn more here.

The tension of the campaign season was palpable. African Americans marching for their candidates and their rights were being met in the streets by armed white supremacists. Conservatives, seeking to stunt the radical agenda of their political opponents, embarked on an aggressive voter suppression effort. Violence hung in the air as the weeks and days crept closer to the November 3 election.

It was 1868, and Americans were voting for president for the first time since the end of the Civil War.

At around 8 p.m. on October 26, 1868, just eight days before ballots would be cast, some 3,000 armed white men gathered in front of Gallier Hall to address New Orleans Mayor John R. Conway. They and the mayor belonged to the Democratic Party, which at the time was predominantly white and embraced conservatism in its party platforms and campaign messaging. In convention earlier in the year the Democratic Party had selected the presidential ticket of Horatio Seymour and Francis P. Blair Jr. and adopted the slogan, “This Is a White Man’s Country; Let a White Man Rule.”

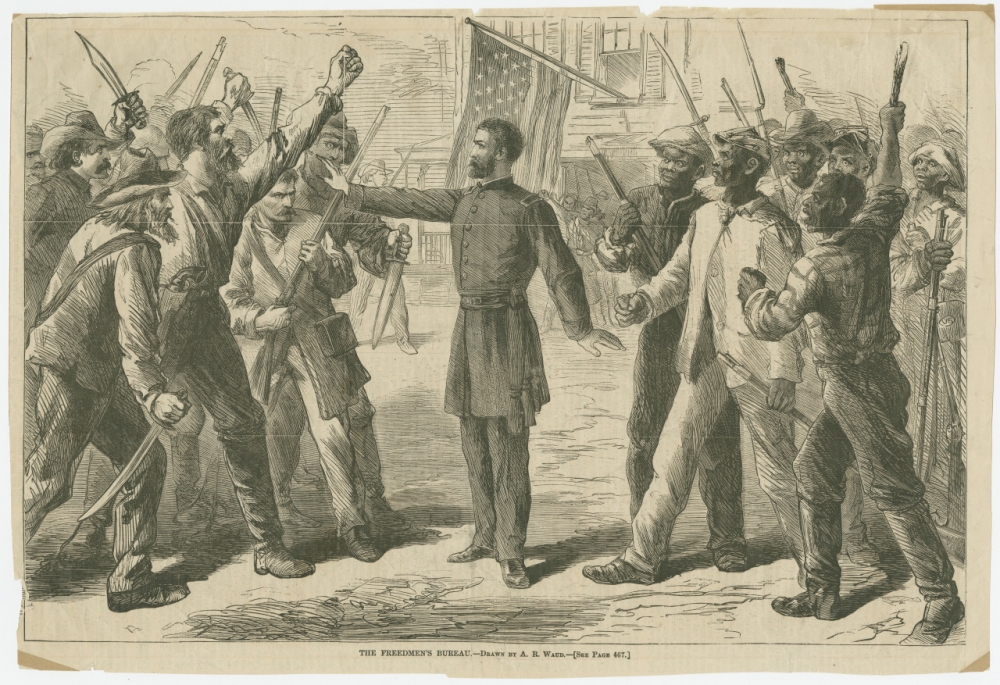

An 1868 illustration depicts a uniformed man from the Freedmen's Bureau separating white and Black people. (THNOC, 1974.25.9.317)

An 1868 illustration depicts a uniformed man from the Freedmen's Bureau separating white and Black people. (THNOC, 1974.25.9.317)

As a result of Reconstruction policy set forth by Congress, the fall election would mark the first time that Black men in the South could vote for president; meanwhile, Congress had limited the voting rights of some former Confederate officials. Riled up by the sociopolitical changes already underway in New Orleans, the white mob chanted racial epithets and called for the death of Ulysses S. Grant, the Union war hero and Republican candidate for president, who was campaigning to permanently enshrine Black male suffrage.

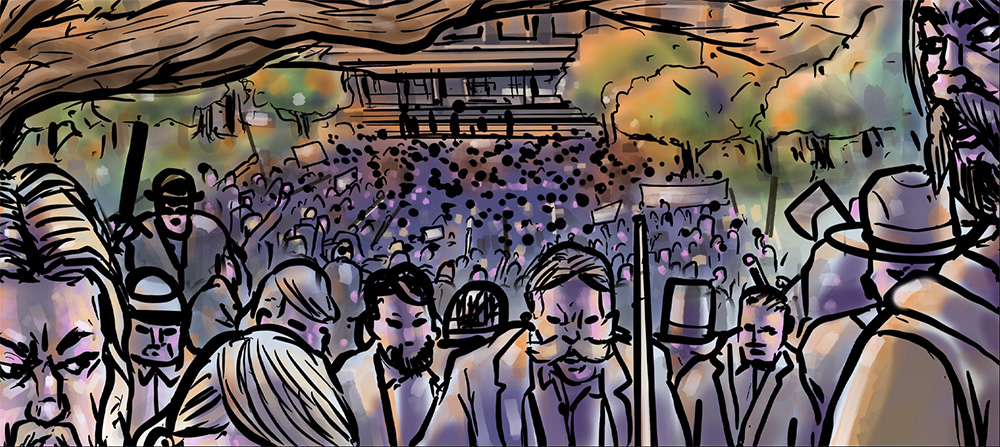

Eight days before the election, New Orleans Mayor John R. Conway asked a mob of 3,000 white men to disperse and that he would “call on them” when needed. (The illustrations in this article are by Barrington S. Edwards and are excerpted from THNOC’s forthcoming graphic history Monumental: Oscar Dunn and His Radical Fight in Reconstruction Louisiana, by Brian K. Mitchell, Edwards, and Nick Weldon. Monumental launches March 6, 2021, and is available for preorder here.)

Eight days before the election, New Orleans Mayor John R. Conway asked a mob of 3,000 white men to disperse and that he would “call on them” when needed. (The illustrations in this article are by Barrington S. Edwards and are excerpted from THNOC’s forthcoming graphic history Monumental: Oscar Dunn and His Radical Fight in Reconstruction Louisiana, by Brian K. Mitchell, Edwards, and Nick Weldon. Monumental launches March 6, 2021, and is available for preorder here.)

After weeks of political violence in the city—instigated largely by groups such as the one gathered at Gallier Hall—the white men came to offer Mayor Conway their support in patrolling the streets. Trying to defuse a volatile scene without explicitly condemning his constituents, Conway reportedly urged the crowd to disperse, “and that when he wanted them he would call for them.”

Six months earlier, as part of Congress’s conditions for its return to the Union, Louisiana had held state elections open to Black men in which voters approved a more inclusive state constitution. A surge of freedmen voters also put a Black man into the lieutenant governor’s seat: the Radical Republican Oscar Dunn.

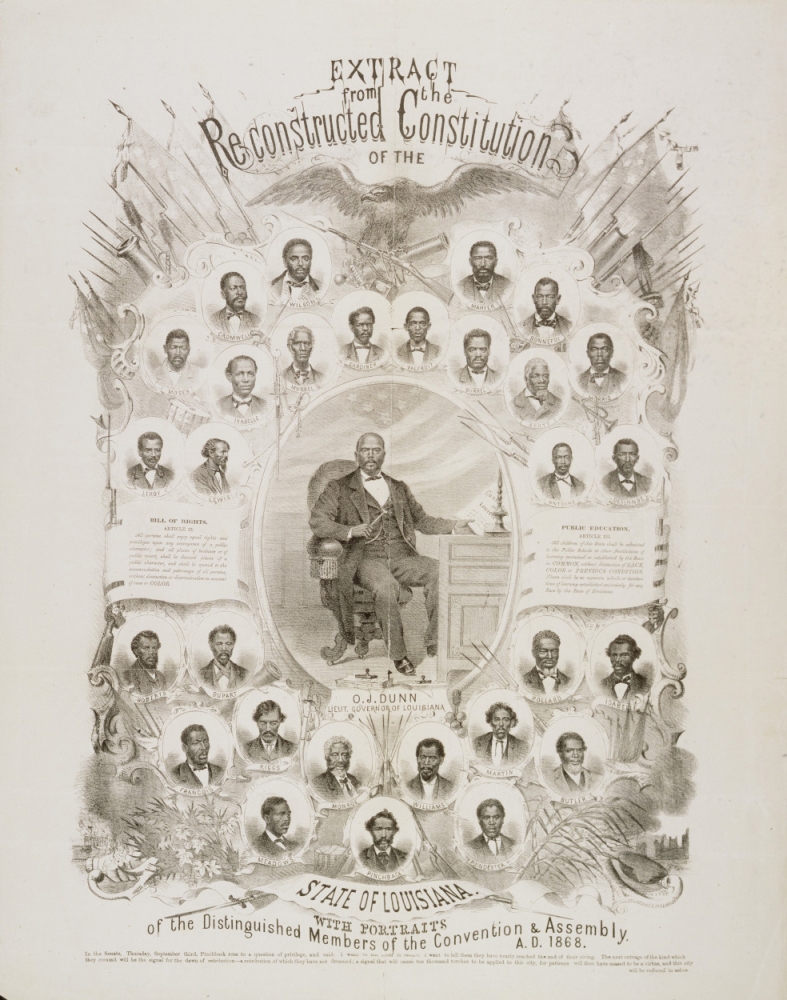

Louisiana's reconstructed constitution provided for black male suffrage and equal rights for all Louisianians in public education and accommodations. This commemorative lithograph depicts the African American men elected to public office in 1868, including Oscar J. Dunn, the first person of African descent elected lieutenant governor in US history. (THNOC, 1979.183)

Louisiana's reconstructed constitution provided for black male suffrage and equal rights for all Louisianians in public education and accommodations. This commemorative lithograph depicts the African American men elected to public office in 1868, including Oscar J. Dunn, the first person of African descent elected lieutenant governor in US history. (THNOC, 1979.183)

Dunn, who is the subject of THNOC’s forthcoming graphic history Monumental, was joined by a wave of fellow Black politicians who entered the state legislature. That body ratified the 14th Amendment, which guaranteed all Americans citizenship rights and equal protection under the law. The implications of Reconstruction had begun to hit close to home for conservative whites in Louisiana, and soon political and paramilitary groups emerged that would spend the months leading up to the election suppressing Black votes by any means necessary.

Black political groups frequently paraded with signs campaigning for the Grant-Colfax presidential ticket. (Illustration by Barrington S. Edwards)

Saturday evenings were popular times for political clubs to parade in the streets, and white Democratic groups would often harass and intimidate Black Republican groups; bloodshed between these clubs on Canal Street, in particular, was common. One particularly notorious Democratic group known as the Innocents numbered around 1,200 and was reported in the New York Times to be “out and parading in the streets in small bands, killing inoffensive black men here and there.” White gangs also broke into Black homes and clubrooms, destroying property, looting, and even stealing voter registration certificates. Anarchy reigned in the city, as armed white militias outnumbered federal troops.

In the rural parishes, where the bulk of freedmen voters resided, white terrorism was even more widespread. A group known as the Knights of the White Camellia harassed, attacked, and sometimes killed politically active Republicans, Black and white, and planned to deploy as poll watchers on Election Day to discourage turnout.

Black voters who did show up to the polls were intimidated against voting for Grant. (Illustration by Barrington S. Edwards)

The voter suppression effort was particularly intense in St. Landry Parish, where a white mob destroyed a Republican printing press and massacred 200 African Americans on local plantations. In April more than 2,500 voters in the parish had supported the Republican Henry Clay Warmoth for governor, but in November, not a single vote out of 4,787 was cast for Grant, the Republican presidential nominee. A local official said “no man on that day could have voted any other than the Democratic ticket and not been killed inside of 24 hours.”

Back in New Orleans, the intimidation effort had worked its way all the way up to the state’s second-highest office. Lieutenant Governor Dunn would later testify to Congress that he and his family were once kept up all night in their home by the sound of gunfire outside. In the days leading up to the election, he avoided going out at night, and in some areas had “heard threats as I passed that they would put that negro governor out of the way.” As a result, Dunn chose not to vote on November 3.

Grant lost Louisiana but won the election decisively, carrying 26 states to Seymour’s 8. In his inaugural address, he endorsed the 15th Amendment, which would prohibit federal or state denial of voting rights based on race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

A month after Ulysses S. Grant’s inauguration, Oscar Dunn visited him at the White House. (Illustration by Barrington S. Edwards)

A month after Ulysses S. Grant’s inauguration, Oscar Dunn visited him at the White House. (Illustration by Barrington S. Edwards)

Congress would later pass a series of Enforcement Acts and the Ku Klux Klan Act to give the federal government authority to prosecute the kinds of fraud, intimidation, and terrorism that marred the 1868 election. Though the threat of violence kept Dunn away from the polls, a month after Grant was inaugurated, the new president welcomed the Louisiana lieutenant governor as the first Black elected official to ever visit the White House.

Explore Black activism in New Orleans through our Symposium 2021 website.