Editor’s note: This story is released in conjunction with The Historic New Orleans Collection’s 2021 Symposium, “Recovered Voices: Black Activism in New Orleans from Reconstruction to the Present Day.” The interactive website includes books, stories, videos, and a March 5–7 program. Learn more here.

President Ulysses S. Grant met Oscar Dunn, the first Black lieutenant governor in the nation’s history, on April 2, 1869. Grant had been in his office less than a month, and Dunn in his less than a year. It was the first time a Black public official had ever visited the White House.

In that initial meeting, Grant and Dunn spoke privately for a half hour—and one can imagine the two leaders taking the time to size each other up. Despite the obvious differences in their color and life experiences, they shared certain characteristics. They were both stout men—Dunn about two inches taller than the grizzled general—and known for their stoic demeanors and straightforward manners of speech.

They were both in their late 40s and latecomers to the political realm, having accepted the power bestowed upon them with some hesitation. Perhaps, in that meeting, they recognized in each other a shared sense of duty to fix what was broken in the nation during this pivotal postwar period of Reconstruction.

When Oscar Dunn met President Ulysses S. Grant on April 2, 1869, he became the first Black public official to visit the White House in US history. (The illustrations in this article are by Barrington S. Edwards and are excerpted from THNOC’s forthcoming graphic history Monumental: Oscar Dunn and His Radical Fight in Reconstruction Louisiana, by Brian K. Mitchell, Edwards, and Nick Weldon.)

Dunn hailed from the Radical wing of the Republic party, which had supported Grant’s candidacy in the 1868 presidential election. Yet Dunn himself did not vote in 1868, kept from the polls—as he later stated to Congress—by fear of violence.

It’s not known whether Dunn discussed his own voting experiences with Grant. Either way, the terroristic voter suppression campaign by white supremacists in Louisiana—and other states with large Black populations—must have been on Grant’s mind. He lost Louisiana in 1868 as a result of the disenfranchisement of voters like Dunn. But he won an Electoral College landslide campaigning on, among other things, protecting the civil and political rights of African Americans.

In his inaugural address, Grant endorsed the Fifteenth Amendment, which would prohibit federal or state denial of voting rights based on race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

At their meeting, Dunn reportedly urged Grant to nominate more Radicals to federal offices in New Orleans. Just 11 days later the president followed through by recommending for US Marshal a man Dunn assured him would have the support of the state’s Black citizens: Stephen B. Packard. Tasked with enforcing federal law in Louisiana, Packard would play a key role in maintaining order in the state.

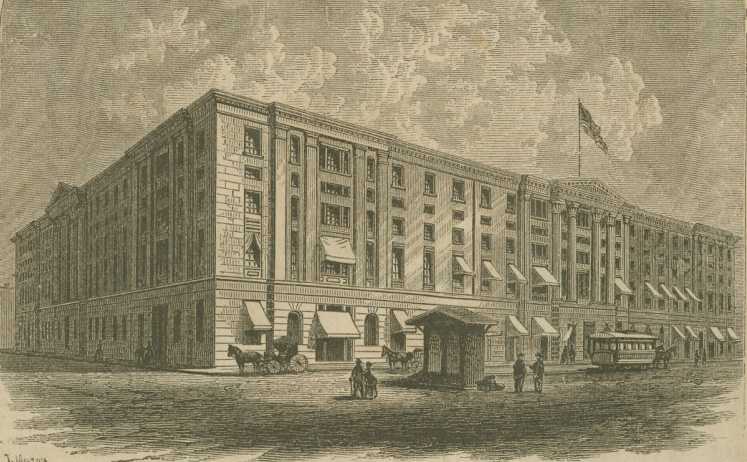

Dunn and Grant had mutual allies in the federal officeholders who worked at the US Custom House in New Orleans (shown here), including Stephen B. Packard. (THNOC, 1974.25.3.189)

At the center of the Republican Party storm in Louisiana was Governor Henry Clay Warmoth, a white man originally from Illinois. Warmoth and Dunn had campaigned together as Radicals committed to improving the lives of freedmen in the state; they took office in July 1868 after being elected with little white support. Warmoth quickly pivoted toward trying to bring more white supporters into the fold, and only months after being elected he vetoed a strong civil rights bill, a decision Dunn and other Black Radicals considered a deep betrayal.

Warmoth’s insistence that the “prejudices” of white people “will surely give way to the softening influences of time” exemplified the challenge to the Radical agenda. Even as he took steps to combat white supremacist terror, Warmoth extended an olive branch to conservative whites, consulting with their leaders and appointing many of them to key judgeships and other public offices.

The identity crisis within Louisiana’s Republican Party mirrored the schism that emerged nationally as Grant and Radicals in Congress acted on a mandate to enforce Reconstruction policy in the South. Congress accordingly passed a series of Enforcement Acts, including the Ku Klux Klan Act, that allowed the federal government to crack down on white terrorists, election fraud, bribery, and voter intimidation.

But these Radical triumphs were built on shaky ground: Southern Democrats and a growing number of Republicans resisted further efforts to meaningfully improve the lives of African Americans in the South. Meanwhile, the party was roiled by infighting over lucrative patronage positions and resentment of perceived cronyism in Grant’s political appointments.

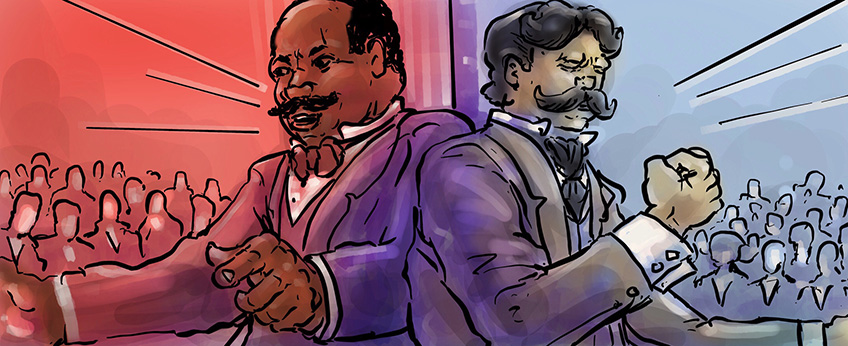

In 1870 and 1871 Grant signed into law a series of Enforcement Acts passed by Congress that allowed the federal government to crack down on the Ku Klux Klan and other perpetrators of terrorism, election fraud, bribery, and voter intimidation in the South. (Illustration by Barrington S. Edwards)

In 1870 and 1871 Grant signed into law a series of Enforcement Acts passed by Congress that allowed the federal government to crack down on the Ku Klux Klan and other perpetrators of terrorism, election fraud, bribery, and voter intimidation in the South. (Illustration by Barrington S. Edwards)

Formed nationally in 1854 and in Louisiana in 1865, the young Republican Party had shepherded the nation through the Civil War. Now, in the fraught postwar era of Reconstruction, the party’s core identity was at stake. And few men—nationally or locally—better understood the stakes than Oscar Dunn.

Frustrated with Warmoth’s deference to conservative Republicans and his outreach to Democrats, Dunn and his Radical faction took steps to challenge the governor’s control of the state party. They cultivated alliances with Grant’s federal appointees in New Orleans. And they cultivated Grant, himself. When intraparty disputes required the direct intervention of the president, Grant’s decisions gave a clear indication of where his sympathies lay.

One such moment came in the wake of the rancorous 1870 Louisiana Republican Party convention, where Dunn was elected convention president over Warmoth. A number of Radicals, including New Orleans Postmaster Charles W. Lowell, levied attacks at the governor for abuses of power and failures to enforce civil rights. Enraged, Warmoth and his allies urged President Grant to remove influential Radicals—including Lowell and Packard—from their posts.

The odds were, perhaps, stacked against Warmoth, for he and Grant had a history: During the Civil War, Grant had dishonorably discharged Warmoth, a lieutenant colonel, for malingering and spreading false accounts of Union losses. Their relationship was strained at best.

At several junctures, Grant intervened in disputes between Dunn and Louisiana Governor Henry C. Warmoth, consistently taking the side of Dunn and his Radical allies. (Illustration by Barrington S. Edwards)

At several junctures, Grant intervened in disputes between Dunn and Louisiana Governor Henry C. Warmoth, consistently taking the side of Dunn and his Radical allies. (Illustration by Barrington S. Edwards)

After Warmoth’s camp had made its case about removing the officials, Grant requested that Dunn and Senator William P. Kellogg of Louisiana meet with him in DC to discuss the matter. Once again, Dunn and the president, now with a third party, sat to discuss Radical federal appointees in New Orleans.

After they met, Grant put the brakes on the removal process, and Warmoth’s efforts eventually fizzled out. A Senate ally of Warmoth wrote to the governor about Grant’s quiet repudiation: “Bottle your wrath, draw your own inferences. . . . We must carry the next state convention at all hazards.”

Grant left no written record of his personal impressions of Dunn. It’s plausible that he was exhausted by the feuding in Louisiana and simply acted with expediency to resolve disputes. But it remains noteworthy that at key moments he consistently sided with the Radicals, acquiescing to requests from Dunn’s camp while ignoring pleas from Warmoth’s. This included before and after that pivotal next convention, where Warmoth and his allies followed through on their vow to carry it “at all hazards”—deploying undercover police and other henchmen to break up Radical meetings and threaten political rivals.

In the lead-up to the 1871 convention, Dunn and his allies wrote and telegraphed Grant on multiple occasions, warning him about political violence and urging him to permit Packard to deputize federal marshals to offer protection at the event. Grant, through his chain of command, permitted it. A chaotic series of events followed when Warmoth’s camp, angered by the military presence at the convention, decided to leave and hold a competing convention elsewhere.

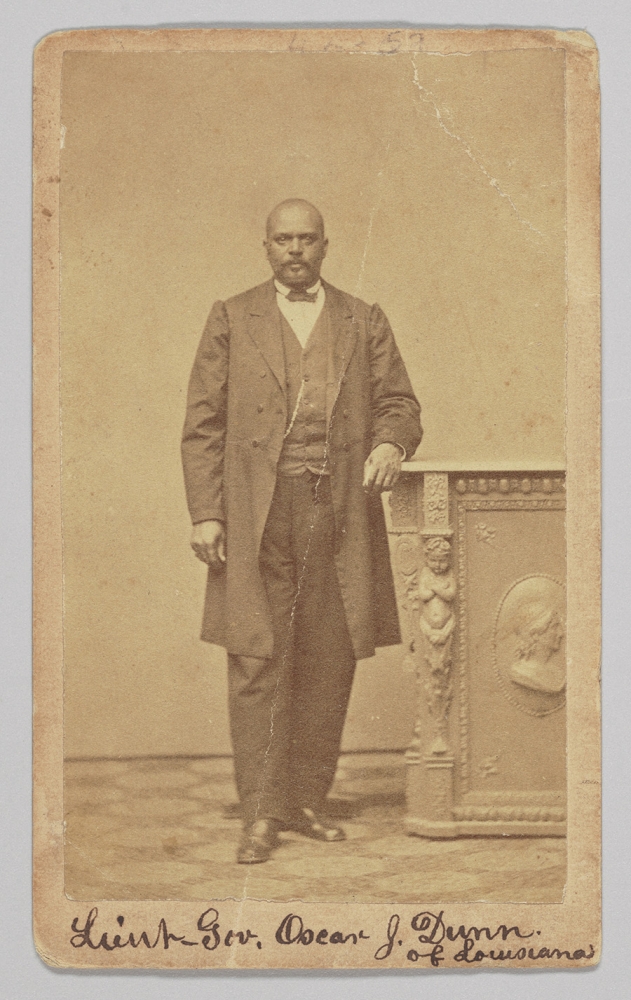

Dunn is pictured in a carte-de-visite sometime during his term as Lietenant Governor of Louisiana between 1868 and 1871. (Image courtesy of the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture)

While Louisiana’s top two public officials quarreled, the announcement by Grant’s second-in-command, Vice President Schuyler Colfax, that he would be retiring at the end of his term inspired speculation about who might join the president’s ticket for reelection. Throughout 1871, newspapers commented on potential vice presidents, with some suggesting an African American candidate. Rumored names included the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, Senator Hiram Rhodes Revels of Mississippi—and Oscar Dunn.

In September 1871 the Galveston News went so far as to suggest that Dunn was “the man most likely to be nominated.” Grant had already made history appointing Ebenezer D. Bassett as minister to Haiti, making him the first Black diplomat in US history, and had placed hundreds of other African Americans in federal positions throughout his first term. Would a Black veep be the next step?

There’s no indication that Grant or Republican Party leaders ever seriously considered any of these names. In Dunn’s case, they never got the chance, as he died suddenly in November 1871. Still, days after his death, the Courier-Journal of Louisville, Kentucky, wrote that “he had the sanction and support of Gen. Grant, and it is believed that the President was willing to take Dunn with him upon the ticket.”

Grant won reelection in 1872 with Henry Wilson, a white Senator from Massachusetts, as his running mate. His second term was plagued with scandal, and by 1876 the era of Reconstruction, with its radical possibilities for Black political leadership, was over. No major political party would nominate a Black person for the vice presidency for another century and a half.

Explore Black activism in New Orleans through our Symposium 2021 website.