October 2, 2020, marks the 100th wedding anniversary of General L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams, founders of The Historic New Orleans Collection. To celebrate this milestone, we look back at their biographies to see how their personal histories set forth the impetus to collect, preserve, and share the history of Louisiana.

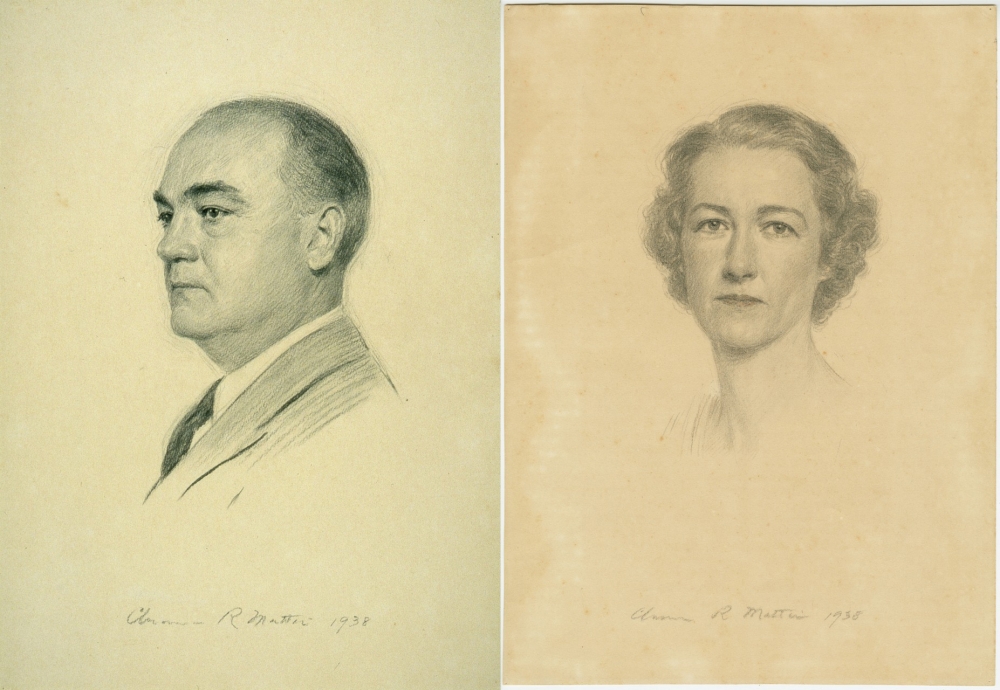

Lewis Kemper Williams (left) and Leila Hardie Moore Williams (right) are pictured in 1938 drawings by Clarence Mattei. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 72.135.1A WR and 72.135.2A WR)

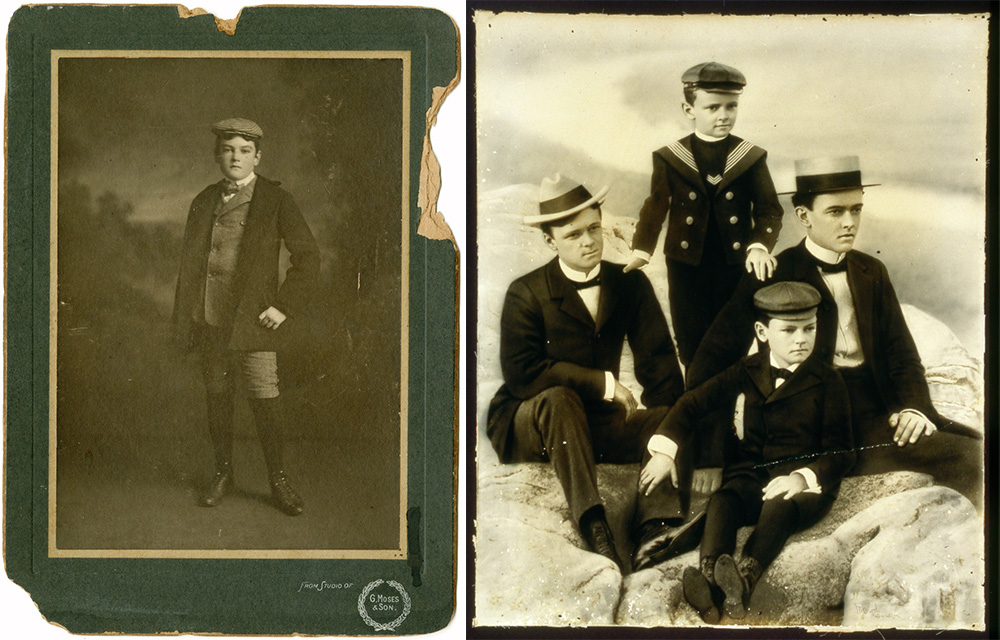

Lewis Kemper Williams was born September 23, 1887, in Patterson, Louisiana, the third of four sons of Emily Seyburn Williams and Frank B. Williams. Frank Williams ran a successful cypress lumber business in the swamps of southern Louisiana, using his experience in the railroad industry to make labor-intensive work more efficient with technology. The F. B. Williams Cypress Lumber Company grew to become one of the largest lumber firms in the country, and Frank Williams became known as the “Cypress King.”

Kemper grew up in a world of stark differences: raised in the swampland of Louisiana but immersed in the wealth of the gilded age. He had the privileges of money, education, and travel, yet remained grounded in his community. This dichotomy can be seen throughout his life in career choices, lifestyle, philanthropy, and collections.

Kemper Williams is shown alone, left, and is featured (seated in the center) with his brothers Charles (far right), Laurence (far left), and Harry (standing). (THNOC, 1980.226.2 and 1985.10)

Kemper left Patterson as a teenager to attend the elite Lawrenceville School in New Jersey from 1905 to 1906 and then to study at the University of the South at Sewanee. Sewanee left a lasting mark on Kemper’s heart, and he remained involved with his alma mater for the rest of his life.

After graduating in 1908, Kemper returned home to work his way up in the family company, starting as a clerk and eventually becoming president and chairman. While working for the lumber company in Patterson, young Kemper made regular trips to New Orleans, especially during the Carnival season. He quickly became one of the set of popular young, wealthy, white men that filled the society pages. His base camp in New Orleans was the Italianate mansion at 5120 St. Charles Avenue, purchased by his parents in 1912, now known as the Latter Branch of the New Orleans Public Library.

Kemper's pre-war base camp in New Orleans was the Italianate mansion at 5120 St. Charles Avenue, what is today the Milton H. Latter Memorial Library. (Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.1502)

After World War I broke out in 1914, Kemper Williams began officer training with the US Army. Commissioned as a captain, he worked to train officers for the rapidly growing army before taking command of a machine gun company. He was promoted to major in October 1918 but was never sent overseas to see action before the armistice in November of that year.

Following the war, Major Williams remained in the Reserve Corps as part of the 347th Infantry Regiment of the 87th Division, headquartered at Alexandria, Louisiana. As a colonel, he helped establish the Reserve Officers’ Association and served as president of that military organization from 1931 to 1934.

Colonel L. Kemper Williams is pictured in uniform between 1930 and 1934. (THNOC, The Kemper and Leila Williams Founders Collection, 00.47)

When Kemper returned home after WWI, he would have encountered a subdued New Orleans. Mardi Gras had been cancelled in 1918 and 1919 because preparations could not be made during the war effort. The city had also suffered several waves of the Spanish flu, and residents were wary of gathering after warnings to stay home. By 1920, the city was ready for a celebration. New Orleans’s privileged sons had returned home from duty, and debutantes were prepared to make up for lost time establishing their place in the social scene. It was in that season that Kemper Williams, aged 33, met the young and lissome Leila Moore, aged 19.

Leila Hardie Moore, daughter of Robert Moore and Leila Hardie Moore, had been born in New Orleans on February 18, 1901, at the home her family owned at 2525 St. Charles Avenue. It was the day before Mardi Gras and, according to family lore, Leila entered the world just after the Proteus parade had passed and Proteus himself had stopped to toast in front of the house. After that auspicious beginning, Leila was destined for a life in New Orleans society.

Life in the Moore family was shaped around the New Orleans social scene. Robert Moore, a native Englishman, was a banker and invested in many New Orleans businesses. In 1907, Moore built a copy of the house at 2525 St. Charles Avenue in Pass Christian, Mississippi, to be his family’s primary residence. Each winter, he rented stylish homes around the Garden District to set up his family for the best access to society and business. As a child, Leila Moore did not stay in one place long, traveling from the family home in Mississippi to England for shopping trips and to the Moores’ summer home in Connecticut. She received her education mostly from governesses, briefly attending a day school in New Orleans before studying at the Westover School in Middlebury, Connecticut.

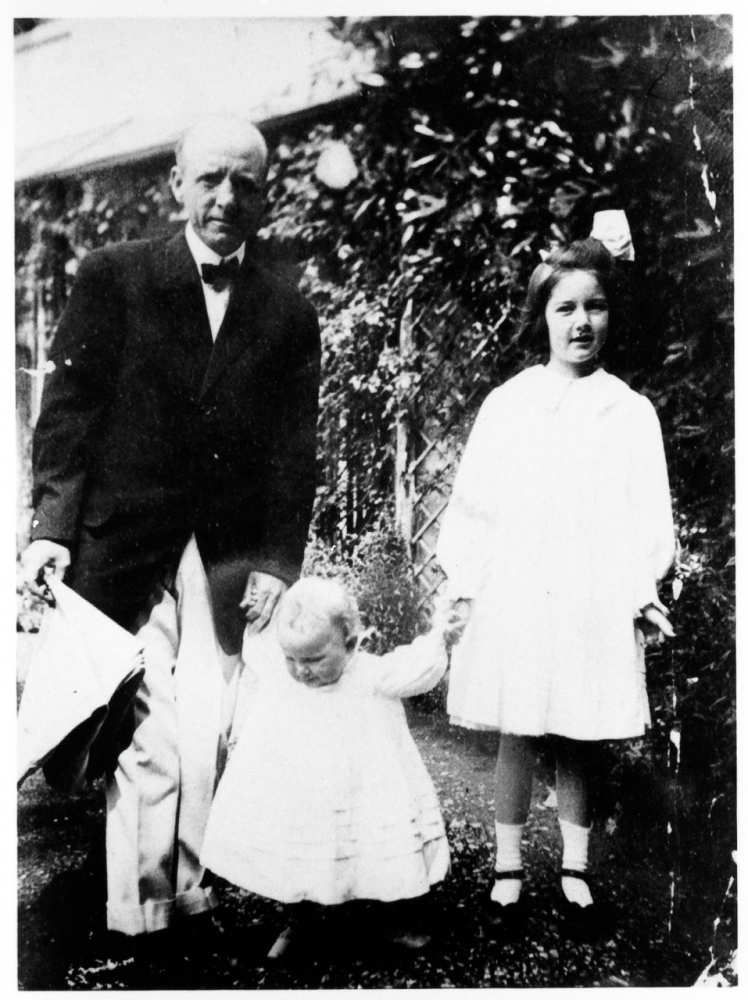

Leila Moore (right) is shown with her father Robert and brother Francis around 1910. (THNOC, 1997.103.2)

The Moores returned to New Orleans each year for the Carnival season, and 1920 was especially important. Not only was it the first celebrated Mardi Gras in years, it was the year in which Miss Leila Moore made her debut. The family leased a spacious home at the corner of First and Coliseum Streets from which they plotted Leila’s social maneuvers. Mrs. Moore hosted a large afternoon reception on December 4, 1919, to formally introduce her daughter to society.

Over the next several months, Leila attended luncheons, teas, supper-dances, soirees, and balls in her role as a debutant. On the first night of Carnival, Leila was a maid in the Court of Peace at the Twelfth Night Revelers ball. (Three courts were chosen, to make up for the lost war years: The Court of Liberty, the Court of Victory, and the Court of Peace.) Almost a month later, Leila served as a maid at the Mithras Ball in the French Opera House.

Somewhere among all of these social engagements, Leila Moore met Kemper Williams. They were engaged by April 1920. Although the couple were 14 years apart, the Times-Picayune stated that “the engagement will not be a surprise to many of the near friends of Mr. Williams and Miss Moore, it will surely claim much attention in the smart world here owing both to the prominence of the two families and to the popularity of the young people.”

The couple were wed on October 2, 1920, at the bride’s parents’ summer home in New London, Connecticut. From there, they set off on a two-month honeymoon to the American west and Hawaii. They were meant to travel to Japan, but Leila caught a stomach bug and they decided to spend more time in southern California. Kemper and Leila fell in love with Santa Barbara, where they would later buy a summer home.

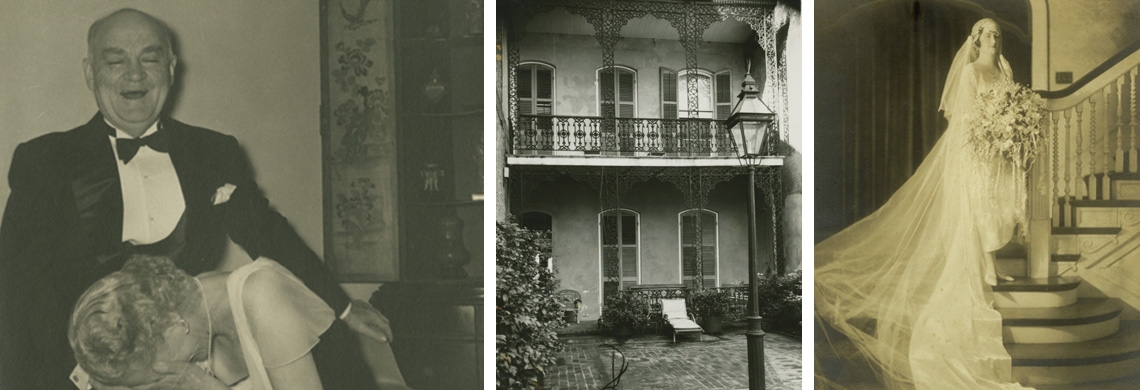

Leila Moore Williams’ bridal portrait was taken on Oct. 2, 1920, by Bachrach Photography. (THNOC, gift of Mrs. Edmund B. Richardson, 1993.71.166)

The Williams established their first married home in Patterson, where Kemper was busy working in his father’s company, first as a secretary, then vice president, and later as president, following his father’s death in 1929. F. B. Williams Cypress Lumber Company began to diversify its interests as the cypress swamps were cleared. In addition to over 85,000 acres of lumber land and state-of-the-art mill technology, the Williams family company invested in the Sterling Sugar mill, Whitney Bank, and a portfolio of stocks and bonds.

Following Frank B. Williams’s death, Kemper and his three brothers began searching for the future of the company, renamed Williams, Inc. in 1931. They almost moved the whole operation to California to harvest and mill virgin redwood forests, but then oil and gas deposits were discovered on the former cypress lands in the early 1930s.

This 1920s video footage depicts lumbering operations of the F. B. Williams Cypress Co. Ltd. in Patterson, La. (THNOC, 1978.24.12.1)

Throughout the 1920s, Kemper and Leila lived in a “cottage” on Idlewild Farm, a dairy farm on the Williams family cypress property. As a young, cosmopolitan bride, Leila may not have been especially excited about the country life. To escape the swamps of Patterson, Kemper and Leila made regular trips to New Orleans throughout the year, often staying with his brother Harry and sister-in-law, the silent film star Marguerite Clarke, at the Williams’ St. Charles Avenue mansion.

The couple also regularly traveled to more distant locations. Each spring they made a shopping trip to New York City, and they often continued on to other destinations from there. Nearly every other year, the Williamses traveled to Europe to take in the sites, participate in the social scene, and bring home souvenirs.

Leila Williams is pictured in the 1920s. (THNOC, 1980.91)

Many of these European tours were shopping trips for young Mrs. Williams as she was establishing her home in Patterson and then, in 1929, on Audubon Street in New Orleans. For her first New Orleans home of her own, Leila worked with interior designer Marc Antony to create a stylish modern home and landscape architect Ellen Biddle Shipman to design the gardens. (Shipman was also designing the gardens at Longue Vue, the home of Edgar and Edith Rosenwald Stern.)

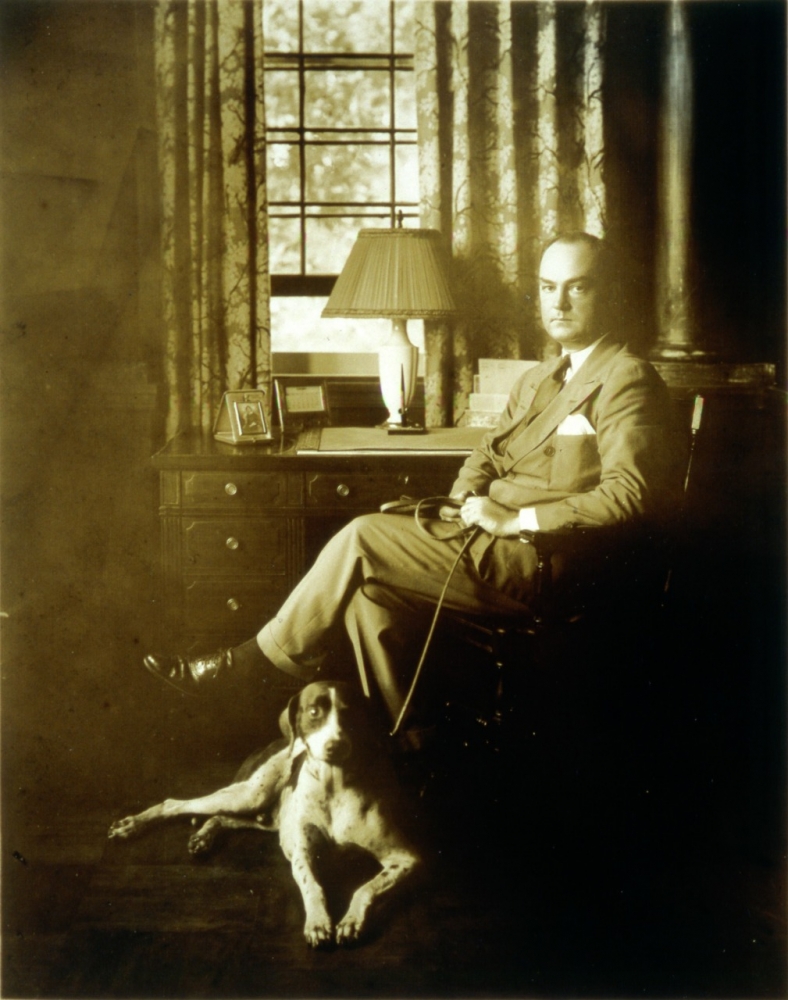

Kemper Williams is shown in his study around 1930. (THNOC, Founders Collection 72.148 WR)

In the 1930s, as most of the country was struggling through the Great Depression, the Williamses turned their civic attention to philanthropy. Leila was a member of many community, civic, and arts organizations, including the Junior League, Women’s Auxiliary of the New Orleans Symphony, St. Anna’s Asylum, and the National Society of Colonial Dames of America in Louisiana. She volunteered at Christ Church Cathedral, where she often provided the flowers for the altar. Leila also donated to a wide range of charities, many focused on education, health, and religion.

Kemper Williams also devoted his time to community and philanthropic efforts. In Patterson, he supported local youth through the Boy Scouts of America. Kemper advocated for army reservists and veterans by helping to form the New Orleans Army and Navy Club of New Orleans and serving as president of the Reserves Officers Organization, an entity that lobbies for the rights and care of reservists. In 1936, Kemper Williams became the first chairman of the Housing Authority of New Orleans (HANO). In this role, he helped the organization get established and traveled to Washington, DC, to lobby for political support to build the first New Orleans housing projects. For his efforts with the Housing Authority, Kemper Williams was awarded the Times-Picayune Loving Cup in 1937.

In 1938, the Williamses’ focus turned to architectural preservation. In that year, at the urging of architect Richard Koch, Kemper and Leila Williams purchased an L-shaped lot in the French Quarter that had frontage at 718 Toulouse Street and 533 Royal Street. The lot had two main buildings on it: the 1792 Merieult mansion that fronted Royal Street with two wings behind it framing a large courtyard, and the 1889 Italianate townhome, built by the Trapolin family, which faced Toulouse Street with a small courtyard in front.

The Williamses contracted with Koch to restore the historic Royal Street building and renovate the townhome to become their permanent residence, but renovations were put on the back burner as the US readied for war in the 1940s. By the late 1930s, Colonel Williams was the commanding officer of the Louisiana Recreational District, which in 1941 became the site of the Louisiana Maneuvers, an army training exercise to prepare 400,000 troops and officers for war.

Colonel Williams is shown with his staff in 1932. (THNOC, Founders Collection, 79-78-L)

After facilitating the Louisiana Maneuvers, Colonel Williams was transferred to Fort Benning in Georgia to command an artillery regiment. In 1943, he moved to the Washington, DC, area, where he was attached to the Army Ground Forces Replacement Depot at Fort Meade, Maryland. Leila Williams accompanied her husband to DC and established their household in Georgetown. Throughout the war, Colonel Williams was a member of the Joint Army and Navy Committee on Welfare and Recreation, eventually becoming Commander of Army Recreation Centers, where soldiers could escape the war for R&R.

In 1944, Colonel Williams joined the Secretary of War’s Disability Board, advocating for disabled and wounded veterans coming home from the front. At the end of the war, Kemper Williams was promoted to brigadier general. From that time on, Kemper preferred to be called “the General.” He retired from service in 1948, after three decades of advocating for the health and welfare of US soldiers.

Throughout the war years, Leila kept a steady correspondence with Richard Koch, who was managing the restoration and renovation of their French Quarter property. In 1945, the Williamses added to the property by purchasing the lot next door at 720 Toulouse Street. This purchase gave them a private courtyard and carriageway leading to the new side entrance of their residence, as well as an additional 18th-century building, which they used as a garage, laundry room, and space for their domestic employees.

The Williams' French Quarter home at 718 Toulouse is pictured here in the 1940s, in a photograph by Richard Koch. (Courtesy of the Vieux Carre Survey)

Kemper and Leila finally moved into their French Quarter residence in 1946. Once again, Leila worked with Marc Antony, and then his protégé Larry Thompson, to decorate the home. The client and designers worked closely together to mix modern and antique pieces, a reflection of Leila’s personal style as well as her interest in travel.

French, English, and other European antiques filled the rooms in the popular muted colors of the immediate post-war era. Collections of beautiful objects, such as jade figurines, Chinese porcelain, or Burmese ox bells, were integrated throughout the home. Contemporary art by local artists such as Boyd Cruise and Enrique Alférez decorated the walls alongside antique maps and prints, hints at what would become one of the most important collections in Louisiana.

Kemper Williams is shown, left, with dachshunds Crackers and Sherry, in front of a mantel carved by Enrique Alférez. Leila is shown, right, in the couple's living room. (THNOC, Founders Collection, 79-78-L.6)

Kemper Williams is shown, left, with dachshunds Crackers and Sherry, in front of a mantel carved by Enrique Alférez. Leila is shown, right, in the couple's living room. (THNOC, Founders Collection, 79-78-L.6)

The Williamses resided in the French Quarter for nearly twenty years and immersed themselves in the social and civic life of elite, white New Orleans. During this period Kemper Williams served as president of the Vieux Carré Commission and was a member of several Carnival organizations, among numerous other memberships and service positions. At their home in the heart of the Quarter, the Williamses regularly entertained other prominent members of New Orleans society, promoting their civic and philanthropic goals and sharing their passion for preserving the history of New Orleans.

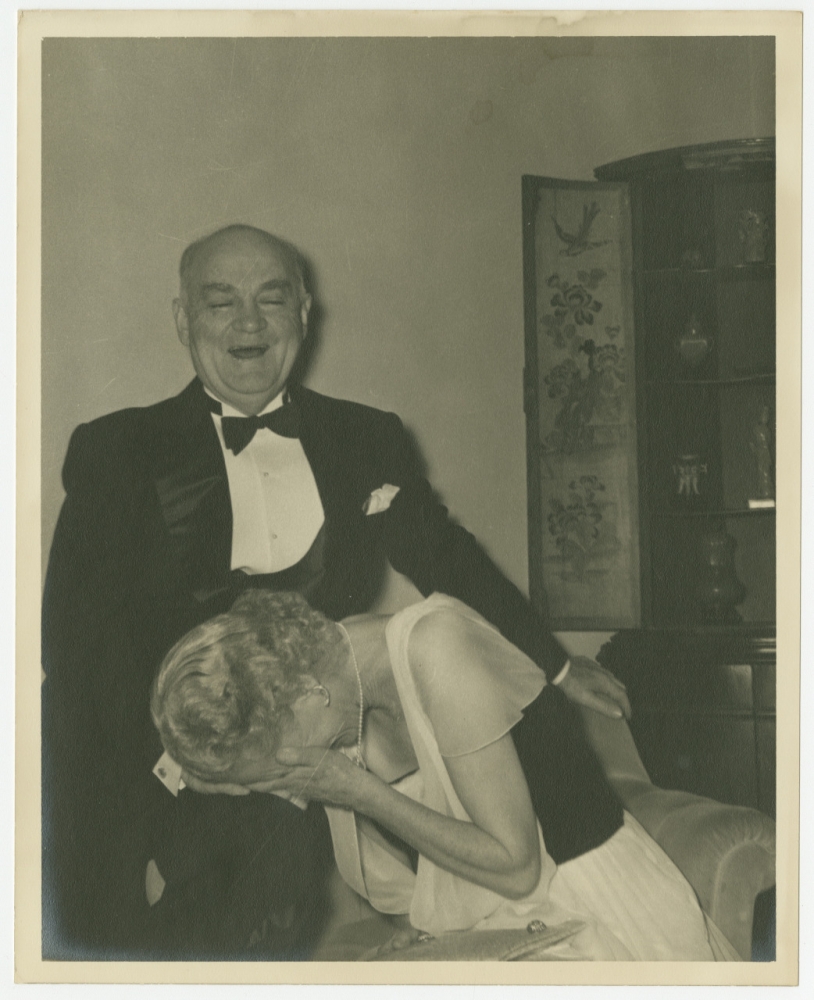

Kemper and Leila Williams host a dinner party around 1950. Formal black-tie dinners were common at the Williams Residence. (THNOC, 79-78-L.3)

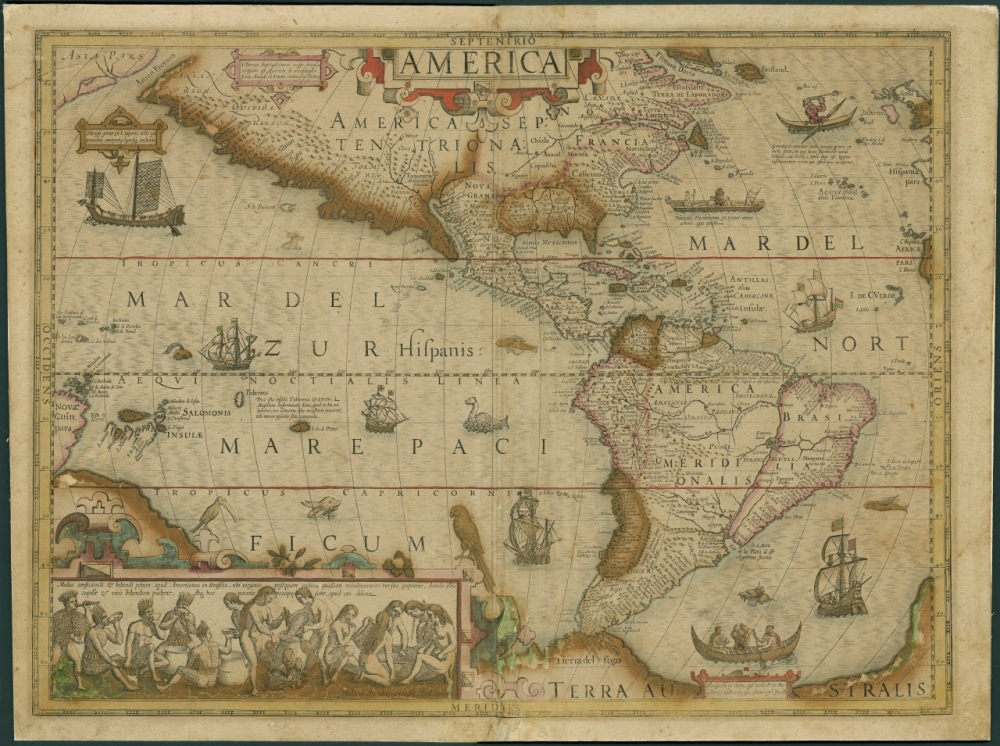

Kemper had had a lifelong collecting “bug,” with interests in military history and cartography, but his collecting became more purposeful in the years he lived in the French Quarter, focusing on acquiring pieces that documented the history of New Orleans and Louisiana. His Louisiana collection had begun in the years prior to the war, supposedly with a gift of ten maps from Leila as a suggestion for a new hobby. From his home in the French Quarter, Kemper created a network of dealers who sought out art, antiques, documents, and books for his collection.

This map, titled America and made between 1606 and 1619, was among the first artifacts in Kemper Williams's collection. (THNOC, Founders Collection, 00.1)

Throughout all his military, civic, and preservation endeavors, Kemper Williams’s main occupation was with Williams, Inc. He was president and chairman of the board of the family company, managing its broad interests in land, sugar, mineral royalties, and investments. From 1953 to 1955, he served as the Honorary Consul of Monaco in New Orleans, broadening his business and social connections to include international relations. The Williamses did receive an invitation to the “wedding of the century” between American actress Grace Kelly and Prince Rainier III of Monaco, but did not attend.

As in her childhood, Leila Williams rarely stayed in one place long. While the Williamses’ main residence was in the French Quarter, they kept two other homes as well. The cottage at Idlewild Farms in Patterson was a peaceful country retreat, and close to the base of Williams, Inc.’s real estate and mineral rights investments. A home in Santa Barbara was the Williamses’ escape from the Louisiana summer. Each year, they moved their household to California from June to October to enjoy the Pacific air. Leila was involved in similar philanthropic work in Santa Barbara, dedicated to art and faith organizations. When not at home in New Orleans or Santa Barbara, the couple enjoyed traveling the world by ship. Kemper and Leila took several cruises in the 1950s, touring the Mediterranean and the Baltic, and circumnavigating the globe on the MS Kungsholm in 1955.

Kemper and Leila Williams’ Santa Barbara home is shown in this 1955 photograph taken by Kemper. (THNOC, Founders Collection, 79-78-L.6)

Kemper and Leila Williams’ Santa Barbara home is shown in this 1955 photograph taken by Kemper. (THNOC, Founders Collection, 79-78-L.6)

The Williamses had no children, but were devoted to each other and their dogs, two dachshunds named Crackers and Sherry. Leila, the graceful hostess, supported Kemper in his professional endeavors by opening her home to guests and maintaining the social-business network. She also encouraged his interests in history and travel, giving him the first set of maps that would become The Historic New Orleans Collection. Kemper cared for his wife through many illnesses, including breast cancer and heart disease. His journal is peppered with references to Leila’s health and mood. He often brought home gifts, stopping in the antiques stores on Royal Street on his walk home from his office.

Leila Williams is shown with Crackers and Sherry around 1955. (THNOC,Founders Collection, 79-78-L.10)

In 1964, Kemper and Leila moved uptown to a large house at the corner of Third and Coliseum Streets. However, they did not divest the French Quarter property. Instead the buildings were devoted to their Louisiana Collection, with the intention of opening to the public someday.

Leila Williams died on December 13, 1966, after suffering a stroke in the dining room of the Pontchartrain Hotel. Her will established the Kemper and Leila Williams Foundation, the operating entity of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

In 1964, the Williamses moved to a home at 2618 Coliseum Street, shown here. (THNOC, 1976.96.2)

Kemper immediately set to work, with the aid of curator Boyd Cruise, to prepare the collection and the French Quarter property for the public. The Merieult house on Royal Street opened in 1970, with galleries dedicated to Louisiana history on the second floor and a research library on the first floor. The following year, Kemper Williams died after falling on the steps of Christ Church Cathedral. His will provided further direction for The Historic New Orleans Collection and stated that the couple’s former home at 718 Toulouse Street should be preserved as an example of the architecture and lifestyle of the French Quarter.

Kemper and Leila Williams are shown laughing in their French Quarter home around 1950. (THNOC, gift of Stephen W. Clayton, 2017.0497.17)

Kemper and Leila Williams were married for 46 years. In their marriage they shared the values of society and community, of global travel and local history, of modern industry and historic preservation. The Williamses’ marriage laid the foundation for The Historic New Orleans Collection, establishing the principles of preservation, education, and community that we strive to carry on today.