Over the course of its existence, New Orleans has frequently endured disastrous flooding and devastating outbreaks of disease due to the insufficient infrastructure of the water system. In 1896, after decades of unsuccessful attempts to drain the city, the New Orleans Drainage Commission was formed to create a water management plan for the city, and by 1899 the Sewerage and Water Board was established. Within a few years, one of its engineers ushered in an era of engineering ingenuity that drastically improved the city’s drainage crisis, decreased disease rates, increased the quality of the water supply, and drove economic growth throughout New Orleans. These improvements, however, came at a mighty cost.

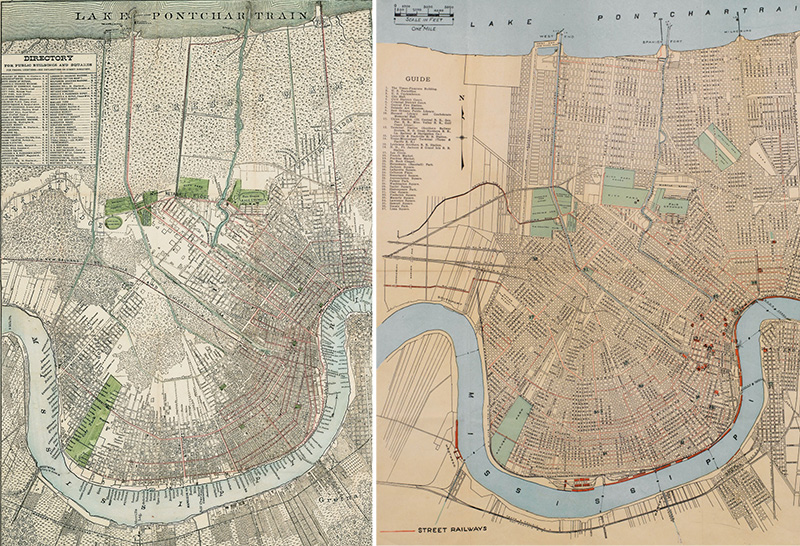

An 1870s map (left) and a 1919 map (right) show the expansion (or planned expansion) of New Orleans toward Lake Pontchartrain over a 50-year period, when a new drainage system opened up vast areas for new development. (THNOC, 00.34 a,b; THNOC, gift of Ambassador and Mrs. John Giffen Weinmann, 2004.0012)

An 1870s map (left) and a 1919 map (right) show the expansion (or planned expansion) of New Orleans toward Lake Pontchartrain over a 50-year period, when a new drainage system opened up vast areas for new development. (THNOC, 00.34 a,b; THNOC, gift of Ambassador and Mrs. John Giffen Weinmann, 2004.0012)

The land on which New Orleans sits formed only a couple thousand years ago. As the Mississippi River flowed to the Gulf of Mexico, it deposited sediment along the way, building up land mass along its banks. The highest ground in New Orleans, known colloquially as the “Sliver by the River,” was the only habitable land when the French settled here in 1718. These areas skirting the Mississippi’s banks received coarser deposits, creating an elevation of 10 to 15 feet above sea level. Land further from the river was formed from finer particles, leaving vast areas of uninhabitable swamp and marshland extending toward Lake Pontchartrain. Contrary to popular belief, these areas including modern-day Broadmoor, Gentilly, and Lakeview sat slightly above sea level before they were developed.

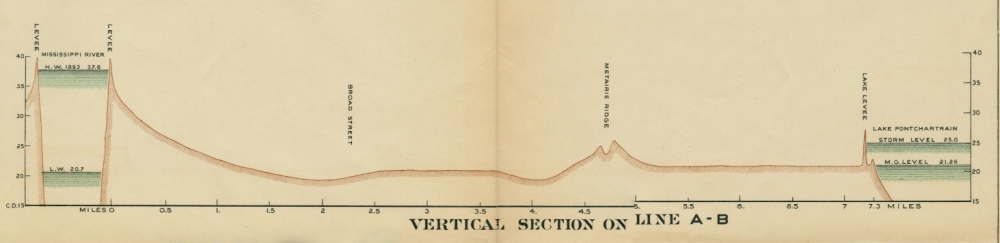

A detail from an 1895 map shows a cross section of New Orleans’s elevation, with the high ground near the river on the left, lower ground over much of the center, and the Lake Pontchartrain levee on the far right. (THNOC, gift of Vivian Blackwell, 2009.0162.10)

A detail from an 1895 map shows a cross section of New Orleans’s elevation, with the high ground near the river on the left, lower ground over much of the center, and the Lake Pontchartrain levee on the far right. (THNOC, gift of Vivian Blackwell, 2009.0162.10)

This quickly changed starting in 1899 when Albert Baldwin Wood, a young engineer newly graduated from Tulane University, found a job with the S&WB as a mechanical engineer. In 1913 Wood applied to patent the Wood screw drainage pump—named for Wood, not made of wood—a 12-foot-diameter pump that moved water up from lower-lying areas and away from the city. The pump relied on a vacuum pipe that brought water up through a rotating impeller to a canal, where the water then flowed to Lake Pontchartrain. At the time it was the largest and most powerful pump in the world.

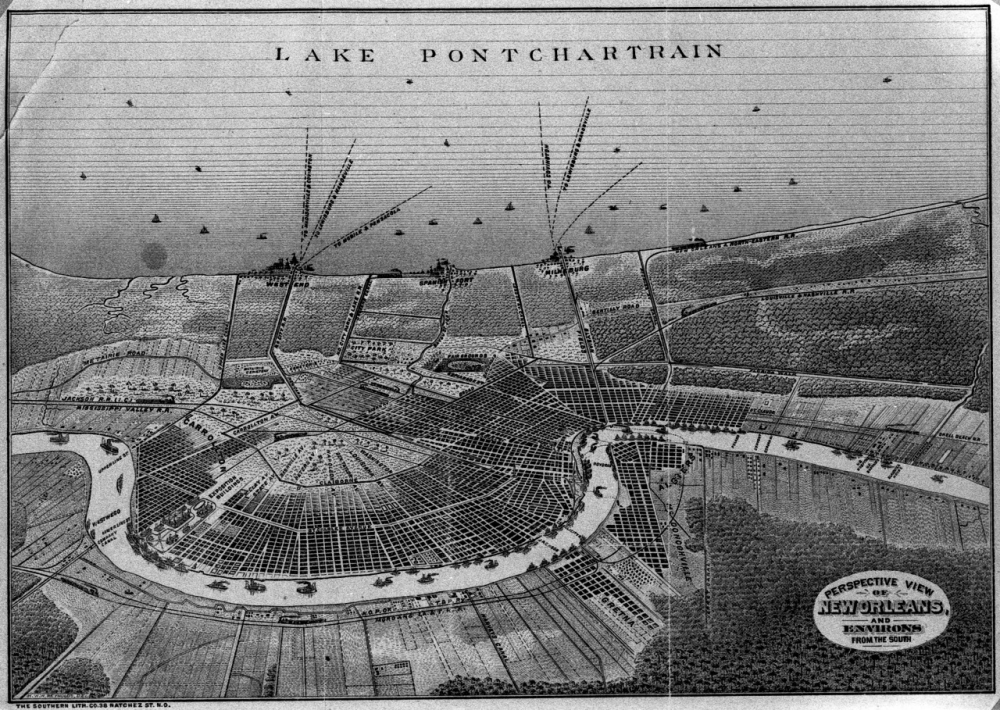

An 1884 lithograph shows the majority of New Orleans’s settled area along the Mississippi River. Few people lived in the lower-lying, swampy areas that extended toward Lake Pontchartrain. (THNOC, 1974.25.18.125)

An 1884 lithograph shows the majority of New Orleans’s settled area along the Mississippi River. Few people lived in the lower-lying, swampy areas that extended toward Lake Pontchartrain. (THNOC, 1974.25.18.125)

Wood then created the centrifugal pump, also known as the “trash pump,” in 1915. His new design could pump record volumes of water, as well as trash and debris as large as a 12-inch-diameter ball, without impairing the effectiveness of the pumps. This feature worked particularly well during major storms, which brought large amounts of debris into the drainage canal. In 1927 the S&WB decided to double the city’s drainage capacity, so Wood designed a 14-foot version of his screw pump, which had the ability to pump one million gallons of water every five minutes.

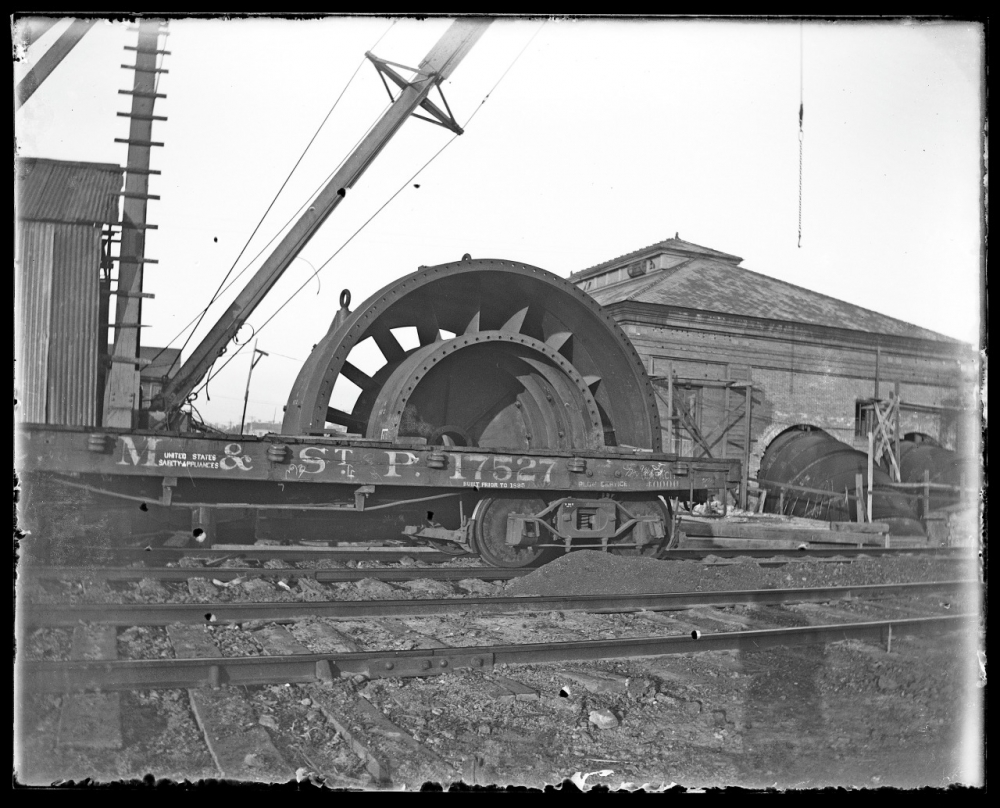

This 1916 photograph shows a large pump part outside of a New Orleans pumping station. Albert Baldwin Wood applied for a patent for his screw pump three years before. (THNOC, gift of Waldemar S. Nelson, 2003.0182.32)

This 1916 photograph shows a large pump part outside of a New Orleans pumping station. Albert Baldwin Wood applied for a patent for his screw pump three years before. (THNOC, gift of Waldemar S. Nelson, 2003.0182.32)

Not only did these inventions help New Orleans keep rainwater at bay, their sheer power started to drain swampy areas like Broadmoor, Gentilly, and Lakeview, turning them into habitable neighborhoods. Wood’s design was also used abroad to help drain parts of China, India, and the Netherlands.

But while these innovations allowed for the exponential growth of the city of New Orleans, progress exacerbated the original problem. As soon as the pumps came on, New Orleans started to experience anthropogenic soil subsidence, or what Tulane University Geographer Richard Campanella called “the sinking of the land by human action” in a 2018 article in The Atlantic.

Here’s how it works: the soil in undeveloped wetlands stays saturated by stormwater and groundwater, which effectively buoy the ground above sea level. But as those lands become developed, and thus drained, the groundwater lowers, soil dries out, and the organic matter decays, causing the land to sink.

A 2014 photograph by David Spielman shows the S&WB’s Pumping Station Number 1 in Broadmoor. (THNOC, ©David Spielman, 2015.0225.73)

A 2014 photograph by David Spielman shows the S&WB’s Pumping Station Number 1 in Broadmoor. (THNOC, ©David Spielman, 2015.0225.73)

In New Orleans, Wood’s pumps—and their successors—have funneled groundwater and organic matter out of the water table for more than 100 years, leaving the dried-out soil to crumble under the weight of the modern city. This has resulted in the fractured roads and potholes that punctuate streets throughout New Orleans—and has caused more than 50 percent of the city’s geographic area to sink below sea level, according to Campanella. In a typical summer downpour, neighborhoods that previously saw little to no water accumulation have begun to flood regularly. Despite widespread suspicion of the S&WB’s capacity to keep the pumps running, the larger issue remains: the system that fights to keep New Orleans dry is sinking the city at the same time.

A man navigates floodwaters in this 1983 photograph by Kurt Mutchler. Soil subsidence has sunk many neighborhoods in New Orleans below sea level, making heavy rainstorms a flood threat. (THNOC, ©Kurt Mutchler, 1985.147.2)

A man navigates floodwaters in this 1983 photograph by Kurt Mutchler. Soil subsidence has sunk many neighborhoods in New Orleans below sea level, making heavy rainstorms a flood threat. (THNOC, ©Kurt Mutchler, 1985.147.2)

“Their intentions were good,” Campanella wrote. “And they thought they were solving an old problem. Instead, they created a new and bigger one.”

So while the city we know and love wouldn’t exist without Wood’s innovative pumps, the current system threatens the long-term resilience of the region. Several plans have been discussed to remedy this: Campanella offers his own solutions, the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan lays out a series of proposals, and the S&WB has outlined its own Green Infrastructure Plan. Suggested innovations include an increased use of greenspace, a focus on water retention systems, and a renewed push to rebuild Louisiana’s wetlands to prevent against the largest flooding events.

The one overarching takeaway: 100-year-old pumps can’t be the sole structures that bail the city out. To survive, New Orleans must innovate again to live with its water for another century.