Just as kings and queens from the mid-15th century on used pipe organs to produce sonic grandeur in their palaces and cathedrals, the industrialists of the early 20th century wanted to re-create classical and popular music in their fabulous houses. Home electricity was the new luxury, and what could be more impressive than an evening spent entertaining under electric lights to the resonant sounds of a massive, self-playing organ?

Electric lights illuminate the organist in a lavish parlor in this 1895 advertisement. (Courtesy of “American Literary History")

Enter the Aeolian Company of New York City, which advertised that it could install a pipe organ in anyone’s home—even on a yacht. Titans of wealth got on board: Carnegie, Ford, Mellon, Rockefeller, Woolworth, Vanderbilt. Some homes had the instruments installed as the walls were going up. Pierre S. du Pont’s residential pipe organ at Longwood, in Pennsylvania, featured 10,000 pipes installed in various chambers around the main music room—above, below, and in wings, to be heard from a distance. Some owners employed famous organists to perform daily. Approximately 1,800 of these instruments were crafted by Aeolian. At the height of the trend there were more than a dozen of them along “Millionaires’ Row” on Fifth Avenue in New York City.

The Aeolian organ is the centerpiece of THNOC’s Barbara S. Beckman Music Room. (Image by THNOC)

One of these behemoths of early home entertainment resides in The Historic New Orleans Collection’s Seignouret-Brulatour Building. THNOC’s Aeolian organ was originally installed in 1925 for William Ratcliffe Irby, a tobacco executive, banker, and philanthropist who purchased the property in 1918. Irby died in 1926, and, within a decade, the Great Depression brought about the end of the Aeolian trend, as the great houses of the age fell into disrepair, were demolished, or were subdivided. Many of the instruments were lost, some broken up, others donated to universities, schools, and churches. The rise of the recording industry and broadcast radio over the ensuing decades definitively marked the end of the Aeolian era. When THNOC purchased 520 Royal Street in 2006, Irby’s organ was one of only a handful in the country left unchanged in their original locations.

Technicians from Holtkamp Organ Company disassemble the interior of the console in 2013, starting off a five-year restoration process. (Image by THNOC)

Early in the process of renovating the Seignouret-Brulatour Building, THNOC decided to pursue a complete historical restoration of the music room, including a full restoration of Irby’s Aeolian organ. The work was entrusted to Holtkamp Organ Company, which deinstalled the instrument in 2013 and sent it to the Holtkamp shop in Cleveland. All aspects of the work were specialized, requiring 12 technicians to address different aspects of the job, from wiring and console hardware to cleaning and voicing the pipes. Of particular interest was the restoration of the player mechanism, which is similar to that of a piano player but much more complex.

The organ has 703 pipes, the majority of them behind two grilles on either side of the fireplace. (The pipes that are visible at the back of the instrument are purely decorative.) The pipes produce sound mechanically, from pressurized air passed through them, but the air is controlled by electric magnets and pneumatic valves. Originally, the 183 pipes known as the echo division—designed to sound as if they’re being played from a distance—were behind a grille in the stairwell; for the restoration, however, the fire marshal forbade THNOC from returning them to what is essentially a tall chimney. Instead, The Collection duplicated one of the grilles and placed the echo unit in a specially designed chamber that allows the pipes to sound throughout the music room.

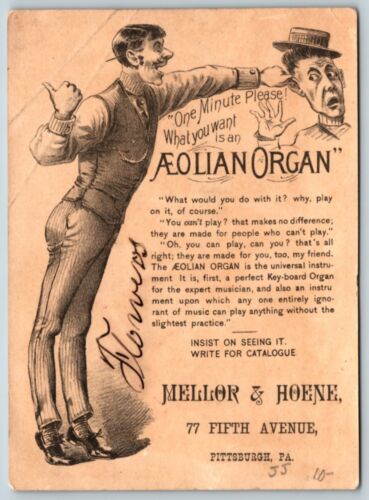

This advertisement stresses that even a person “entirely ignorant of music” can play the instrument. (Courtesy of eBay)

Advertisements proclaimed that consumers did not need any skill, talent, or training to play an Aeolian organ. Thanks to the player mechanism, users could insert a roll, sit back, and enjoy. Irby purchased an unknown number of rolls from Aeolian’s 2,000-item catalog. At the time, sound recordings were limited to about three minutes of music, but rolls could provide up to 15 minutes of entertainment. In addition to refurbishing the original player unit, Holtkamp added a MIDI unit, a digital device that allows the modern organist to record music for playback on demand.

Three organ rolls—Carmen Fantasie, by Georges Bizet; William Tell overture, by Gioachina Rossini; and Berceuse no. 19, by Louis Vierne (THNOC, 2020.0172)

The video below helps illustrate the complex inner workings of the organ and gives viewers a rare glimpse inside the instrument while it plays an Aeolian organ roll recorded by Louis Vierne (1870–1937), famed organist and composer of Notre-Dame Cathedral.

Visitors can learn more about the Aeolian organ and hear a musical sampling by scheduling an organ demonstration.

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.