Calvin Dayes made shoes fit for a king, but more importantly, he made shoes fit for those who most needed them. For decades, Dayes crafted the thigh-high, white, kid-leather boots worn by Rex, as well as by other monarchs, on Mardi Gras. He also made custom orthopedic shoes for those with foot ailments. Regardless of the reason or the occasion for his specialty shoes, each finished piece featured a truly unique label: “By the JiveAss Shoemaker.”

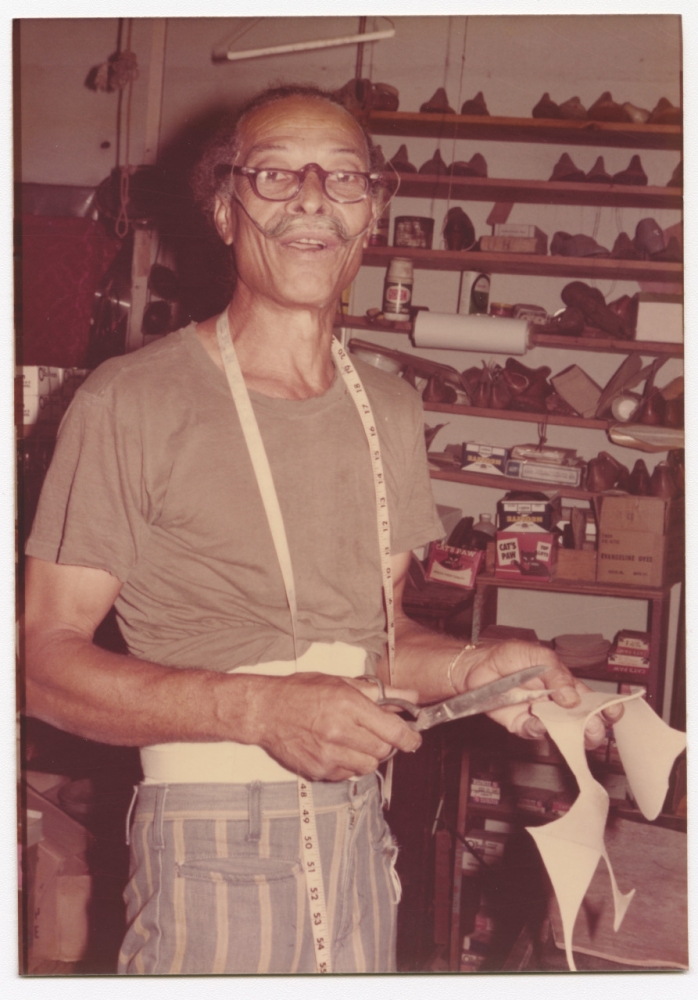

Calvin Dayes is shown in his workshop in the 1980s. (THNOC, gift of the estate of Jive Ass Shoemaker, 2018.0372.3.10)

Dayes’s friends called him “the Shoemaker.” He sported a Salvador Dalí-like waxed mustache, and late in life grew a fluffy white beard to go with it. He worked to the sounds of jazz mixtapes he arranged himself. Simply put, he was one of a kind.

Born in Kingston, Jamaica, alongside his twin brother Alvin, Calvin Dayes (1923–2012) studied the cobbler trade as a child, and had made his first pair of shoes by the time he was seven years old. Dayes got his first taste of the United States in the mid-1940s when he worked as an agricultural laborer in Florida for a few months. When he returned home to Jamaica, he itched to return to the US.

In 1949, he stowed away on a British naval ship, arriving in New Orleans several days later with only $38 in his pocket. He found a job with a chemical company, saving his earnings until he was able to start his own shoe business a few years later. By 1960, he opened the Dayes Shoe Hospital at 3101 Carondelet Street, later moving the business uptown to Freret Street near Carrollton Avenue.

This carved wood “Boot Maker” sign was among the materials acquired from Dayes’ estate. (THNOC, gift of the estate of Jive Ass Shoemaker, 2018.0372.1.1)

The Shoemaker was one of the few skilled cobblers in town, and built a reputation for making elegant, supportive shoes for feet of all shapes and sizes. He worked with George A. Schroth & Sons to provide prescription shoes for those who needed them. Doctors from across the Gulf South sent their patients to him for specialty shoes for all ailments.

Dayes’ clientele included veterans, factory workers, society ladies, children in orphanages, and the Catholic nuns who cared for them. Dayes could make sturdy shoes to support weak ankles, strong shoes incorporating braces to help strengthen legs, giant or petite shoes for feet of uncommon sizes, or flexible shoes to fit bunions or missing toes.

Calvin Dayes produced footwear to address all kinds of maladies, including this special orthopedic shoe with a platform sole and leg brace. (THNOC, gift of the estate of Jive Ass Shoemaker, 2018.0372.1.4)

For every client—from Carnival kings to children in need—Dayes started his work by tracing their foot on a paper grocery sack. The Shoemaker made his measurements and then created a custom last, or shoe form, for each customer, building up from a standard wooden form with layers of leather, or shaving away excess material to match the shape of the customer’s foot.

From this form, he crafted shoes from the best materials to fit his customers’ needs—such as sturdy or supple leather, or substituting cork for the sole to make it lighter—weaving every stitch by hand.

Each custom shoe began with an outline of the customer’s foot, and from that a custom shoe last, or shoe form, like the ones shown here were made. (gifts of the estate of Jive Ass Shoemaker, THNOC, 2018.0372.1.8, 13, 15)

Good craftsmanship takes time, and the Shoemaker refused to be rushed. He was known to keep customers’ checks pinned to their lasts, and if they bothered him before the shoes were ready, he’d simply return the money and stop work on the shoes.

Without a prescription, Dayes’s shoes could be expensive—up to $1,200 for a pair of Carnival boots—but, if the customer was patient, they’d get shoes that were the perfect fit and would last a lifetime.