American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith, created by the Smithsonian Institution’s Traveling Exhibition Service, examines the continuing evolution of America’s experiment in government “of, by, and for the people.” The show includes a wide selection of reproduction print materials from the period of the American Revolution. These political cartoons, patriotic symbols, colonial newspapers, and political pamphlets demonstrate the crucial role of print media in building support for United States independence. Print media spread political ideas, inspired rebellion, and encouraged colonists from different regions to identify with the new nation.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

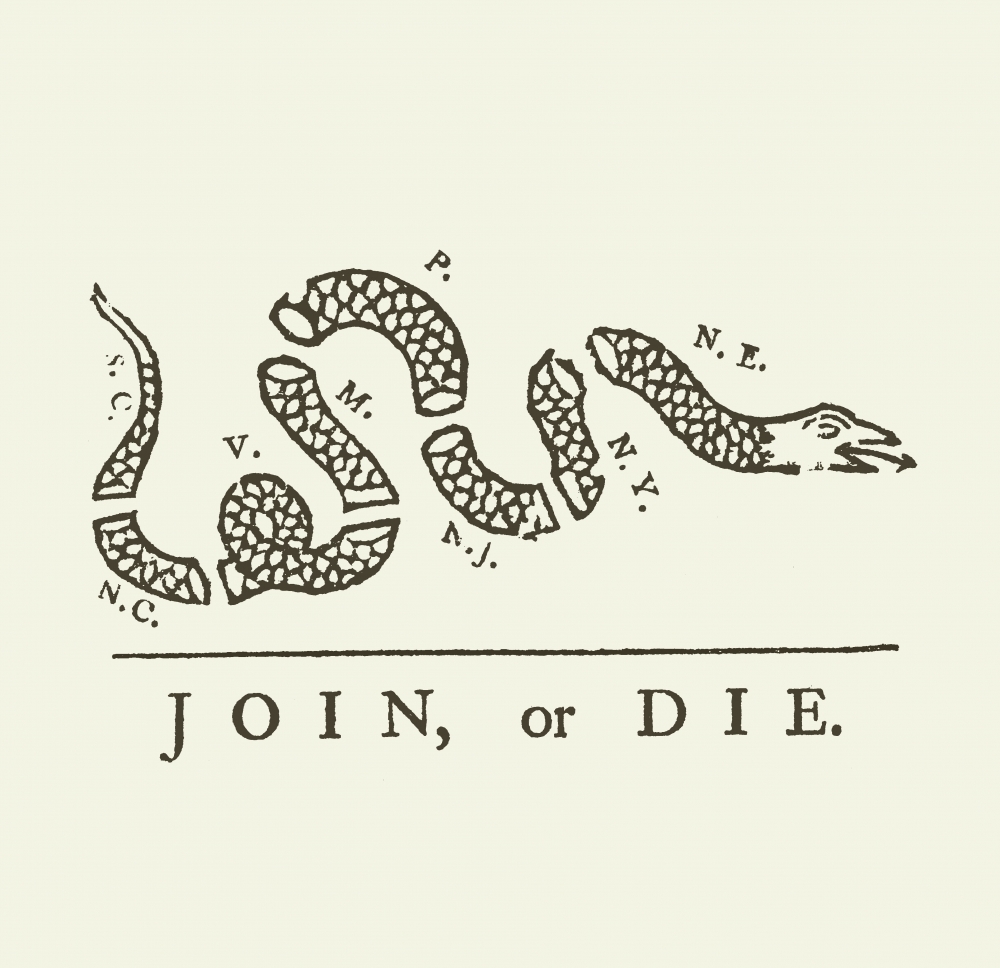

Widely published woodcuts and cartoons could express political thought in vivid and memorable terms, becoming powerful symbols of resistance and national identity. One of the most enduring symbols of American unity in the colonial era is Benjamin Franklin’s Join, or Die woodcut. Franklin originally designed and published the image in his newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, in 1754 to promote solidarity against foreign enemies during the French and Indian War. He reused it in the 1760s and 1770s to urge united colonial opposition to Parliament and the king.

Inequality with their peers in Great Britain as well as a series of new taxes fueled tensions in the original 13 colonies. Opposition in the 1760s crystallized around tariffs that bypassed elected assemblies in the colonies. Americans argued with increasing agitation that Parliament should not enact colonial laws. Instead, legislators who enacted colonial laws should be chosen by colonial voters and share basic interests with their constitutents. The 1765 Stamp Act imposed a tax on newspapers, pamphlets, and legal documents. As colonial legislatures submitted petitions of protest to Britain, the people expressed their outrage in the streets.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

British officials and troops were sent to enforce the unpopular laws, leading to intense confrontations between soldiers and civilians. On March 5, 1770, British soldiers in Boston fired into a crowd, killing five men. Paul Revere, a silversmith and activist, created prints of the event that would become known as the Boston Massacre to spark more unrest.

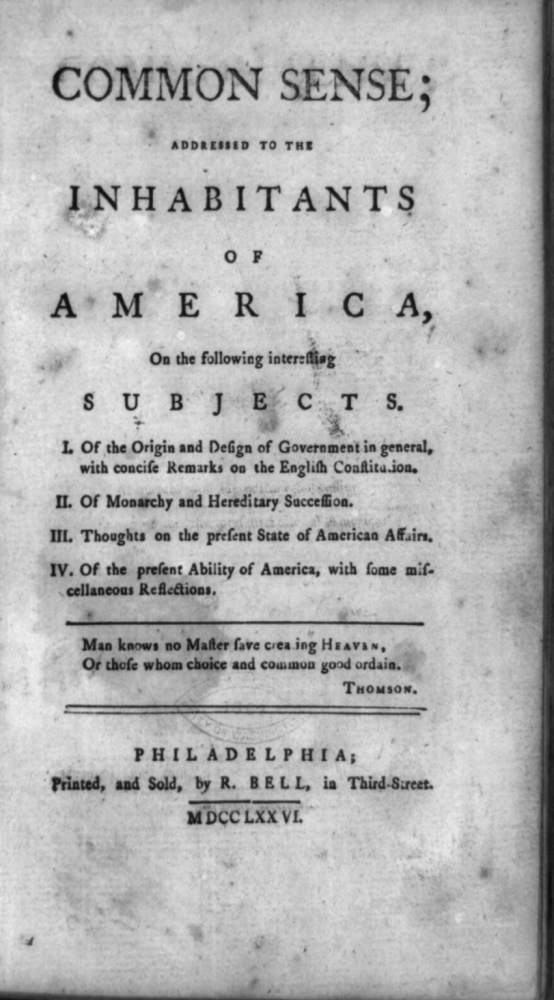

While printed images stirred passions, colonists also had access to more intellectual appeals for independence. Pamphlets, cheap and easy to print, brought political theory into the hands of everyday people. They discussed these ideas in taverns, important gathering places for exchanging information. Many taverns had reading rooms stocked with newspapers and political tracts, and speakers would often read the latest news aloud for illiterate members of the public. Rum toasts denouncing British tyranny might be followed by a reading from Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, the wildly popular 1776 essay that makes an impassioned appeal for egalitarian government, praising the common sense of the common people to rule themselves, free of monarchs and aristocrats.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

“Nothing but a newspaper can put the same thought at the same time before a thousand readers,” wrote Alexis de Tocqueville in his 1840 study Democracy in America. Images of momentous events moved fast through an impressive network of colonial newspapers and printers. Newspapers also spread accounts of protests and legislative debates to far-flung readers, allowing people from Massachusetts or Georgia to see themselves in a common political struggle. While colonies often had very different social and economic interests, newspapers presented issues that united them.

After the defeat of the British, in the summer of 1787, delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia met in private, forbidding press coverage of their deliberations over the form the new American government would take. In September Americans had their first chance to see a draft of the proposed constitution, when it was published in the Providence Gazette, Boston Gazette Journal, and other papers around the nation.

A great debate followed—much of it playing out in newspapers—about whether the colonies should ratify, amend, or throw out the document. The Massachusetts Centinel published a series of cartoons depicting each state as a pillar on which the new nation would stand. One print from 1788 shows the first five states to ratify the constitution.

The constitution was formally adopted on June 21, 1788, when New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify it. Newspapers and other forms of print had supported passing the constitution, but in the years that followed, their relationship with the federal government was often tense. In 1798 the John Adams administration passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, intended to suppress criticism of the government by the press. Intense controversy around these laws led to their repeal in the early 1800s.

As the United States emerged as a young republic on the world stage, print media played the critical role of inspiring support for rebellion, building a sense of shared purpose, and providing people with necessary information so they could exercise their new political power.

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.