They attacked Shakira in Barcelona. They’re “rampaging” in San Francisco. In November, they appeared in New Orleans East, tearing up yards and putting residents on edge. Proliferative, destructive, and seemingly irrepressible, feral hogs have rapidly become one of the most challenging invasive species on the planet. Once primarily a nuisance in rural areas, the “pig bomb,” as South Carolina–based feral hog expert Jack Mayer calls it, has arrived at the doorsteps of cities like New Orleans. “The urban incursion by wild pigs is kind of a global phenomenon right now,” Mayer says. “Hong Kong has a major problem, Rome, cities across the globe—in part because populations have grown to the point that they’ve expanded into developed areas.”

Approximately 900,000 feral hogs currently roam Louisiana, across all 64 parishes. They reach sexual maturity between six and eight months of age and can produce up to two litters of as many as a dozen piglets a year—meaning the latest population figures are outdated almost as soon as they’re published. The Louisiana State University AgCenter estimates that feral hogs cause $76 million in agricultural damage annually in Louisiana, destroying everything from sugarcane to rice to corn, and their rooting behavior also damages levees. Known as “opportunistic omnivores,” they outcompete many native species for resources, prey on animals as large as baby deer, and even threaten alligators by destroying their nests and eating their eggs. They also can carry dozens of viral and bacterial diseases, many of which can infect humans and livestock. On top of all that, feral hogs are highly intelligent animals that will defend themselves if threatened. Local hog hunter John Schmidt, better known as Trapper John, puts it succinctly: “They’ll fight till their last breath.” If they’re not fighting, they’re hiding, and they’ve proven quite adept at eluding capture in the forests and swamps of Louisiana—in part, because they’ve had a nearly 500-year head start.

The Long, Curly Tail of Colonialism

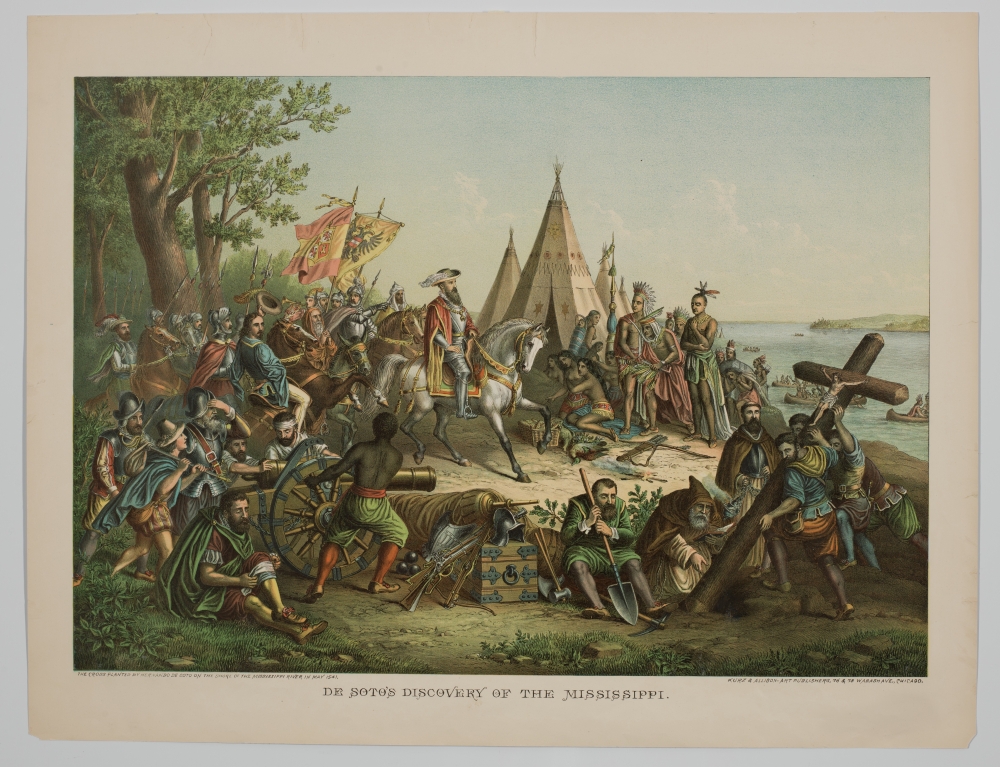

It began with an invasion of another kind, when in 1539 Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto brought soldiers, enslaved people, horses, and as many as 300 domestic hogs into the territories of various American Indian tribes in what is now the Southeastern United States. Historians generally agree that this was the first time pigs (domesticated or otherwise) appeared on the North American continent. Sus scrofa—the scientific name for all wild and domestic swine—helped sustain many European colonization efforts due to their ability to reproduce quickly and adapt to a wide range of environments. When de Soto died of an illness on the banks of the Mississippi River in either present-day Arkansas or Louisiana in 1542, his herd of pigs had already grown to 700, and along his 3,000-mile journey many of the animals had escaped or ended up in the possession of local tribes.

Hernando de Soto (on white horse) introduced hogs to North America. At the time of his death on the Mississippi River in 1542, his will listed 700 hogs among his possessions. (THNOC, 1982.247)

Spanish colonists knew they had a pig problem long before de Soto’s ill-fated trek. The species had first been introduced to the Caribbean in 1493, when Christopher Columbus brought eight domestic swine to the island now known as Cuba. Columbus’s hogs quickly multiplied and were used to stock islands throughout the Spanish West Indies. Their ever-growing herds soon began terrorizing the islands, destroying maize and sugarcane crops, killing cattle, and even attacking people. Still, de Soto and many colonists after him took hogs from this stock with them on their voyages throughout the region. The Spanish were joined in transporting hogs to North America in the coming centuries by English and French colonists, including René-Robert Cavalier, sieur de La Salle, and Pierre Le Moyne, sieur d’Iberville, who brought hogs to Biloxi in January 1699. Many of these hogs and their offspring went feral because owners typically allowed them to range freely without fencing. These wild populations found cover in the forests, at the edges of human habitation, and reproduced unchecked.

A Royal Obsession

By the 19th century, feral hog populations in the Southeastern US had become a well-established nuisance. Newspapers frequently covered the exploits of rogue hogs, such as one “notorious” 468-pounder that in 1851 harassed residents near Savannah, Georgia, until finally being killed by a group of men and dogs. The backyard pig once seen as a reliable source of food had evolved into something else: a mythical menace of the woods. The press enhanced stories of close encounters on the home front with fantastical yarns of wild boar hunts carried out by European royalty. Those who could bag a boar with sizable “tushes”—slang for tusks—returned to a hero’s welcome. The Daily Picayune described one such homecoming on its front page on February 2, 1876, detailing the “splendid capture” of a 275-pound boar near Fort Macomb. Its brave captors, identified as H. Montreuil and A. E. Livaudais, proudly displayed the boar’s head at the Gem Saloon on Royal Street. The paper promised, “There are doubtless many more wild boars on the prairie, and further splendid sport is expected.”

In 1895 the Boston-based Outing magazine published an especially romanticized account of a boar hunt at an unnamed Louisiana plantation. “Of all sport none is more exciting, more abundant in surprises, more replete with dramatic situations, than hunting the wild boar in a Louisiana forest,” wrote George Reno in his first-person retelling. “Compared with it, shooting birds becomes tame, killing deer seems murder, and fishing, as you think of the time wasted between bites, absolutely spiritless. . . . You may have, if not careful, a chance to exchange places with your game, and become the hunted, instead of the hunter.” Or, in Reno’s case, a chance to watch comfortably from his horse as two Black guides named Dick and Simpson and their trained dogs led a dramatic and victorious boar chase through the Spanish moss–draped woods. The dogs were in all likelihood Catahoula leopard dogs, or Catahoula cur, a native breed of Louisiana. Hunters have trained Catahoulas to hunt wild boar here for hundreds of years, and Gov. Edwin Edwards declared the breed Louisiana’s state dog in 1979.

Catahoula leopard dogs, also known as Catahoula cur, are native to Louisiana and have long been used by hunters to track down wild boar. (From the Michael P. Smith Collection at THNOC, 2007.0103.7.34)

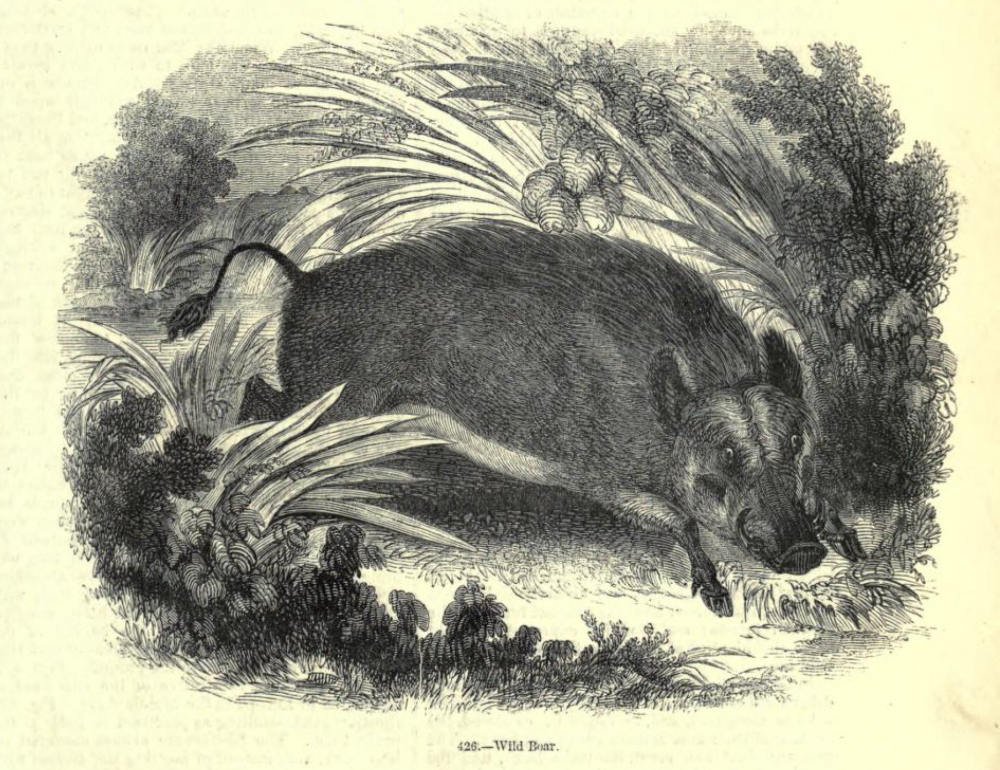

“Boar” is the technical term for all adult male swine, but it began carrying a notable distinction as hunting feral hogs for sport became more popular in the US. The animals hunted by European royals were likely actual Eurasian wild boar—the progenitor of all domestic and feral hogs. Though it’s the same species, the Eurasian boar bears notable physical differences from its descendants. Pure Eurasian boars tend to have darker and coarser fur, longer legs, larger heads, and, importantly, bigger tushes—er, tusks. “If you have a choice between shooting something that looks like a scrawny Hampshire boar or a Eurasian wild boar,” Mayer says, “you’re gonna want the Eurasian wild boar.”

Despite the casual use of “wild boar” in media accounts of hog hunts in the US in the latter half of the 19th century, the first documented introduction of pure Eurasian wild boar in the country didn’t occur until 1890, when millionaire Austin Corbin imported 13 boar from Germany to his private reserve in New Hampshire. Thus began a wave of wealthy white men importing Eurasian wild boar onto their vast estates: Edward H. Litchfield in New York in 1902, George Gordon Moore in North Carolina in 1912 and in California in 1924, Leroy G. Denman Sr. in Texas in 1919, and more. These wealthy hunters, ironically, became the feral hog’s best friend, popularizing a sport that relied upon healthy populations. Meanwhile, their boars—as they are wont to do—got out. And multiplied.

This engraving, from The Pictorial Museum of Animated Nature (1844), shows the curly tusks and thick, coarse fur that have made Eurasian wild boar a popular object of sport hunting for centuries. (Courtesy of the Biodiversity Heritage Library)

Breaking Loose

Free from their enclosures, these Eurasian boar met members of the established S. scrofa population in the US and, being almost genetically identical, began producing hybrids that over time picked up the best traits of their ancestors and spread like wildfire. “Hybrids get this two-part coat where they can survive in the snow and can live on the equator,” says Buddy Goatcher, a wildlife biologist with more than four decades of experience trapping and hunting wild hogs in Louisiana and elsewhere. “They’re super survivors.”

To help fight back against suddenly booming feral hog populations in the early 20th century, eastern and southern states passed livestock fencing laws that in many areas ended free-ranging practices that dated to the early colonial eras. A 2014 federal report on wild pigs in Louisiana and Mississippi, co-authored by Goatcher, noted that “during the Great Depression (approximately 1930–40) and following decades, wild pigs were almost eradicated, except in those wards, parishes, and counties where government officials and local statutes protected pig free-range practices.” By the early 1960s, there were only 7,500 feral hogs in Louisiana—less than one-hundredth of today’s total—largely contained to areas with longstanding free-range populations, such as in the vicinities of Catahoula Lake and the Pearl River. The federal government had purchased the land around Catahoula Lake in 1958 and fenced in portions of it, and “through an ongoing extermination program both the [Catahoula National Wildlife Refuge] and the Sabine WMA [Wildlife Management Area] were practically free of feral hogs by the late 1970s,” according to Wild Pigs in the United States, by Jack Mayer and I. Lehr Brisbin.

Despite these initiatives, feral swine found a way to bounce back, with some help. The Eurasian wild boar still enchanted wealthy sportsmen, and Leroy Denman’s Powderhorn Ranch on the Texas Gulf Coast had plenty of them—too many, it turned out. Dennis Good, an avid outdoorsman from Belle Chasse, recalls in the early 1970s being invited to hunt boar that had escaped from Powderhorn onto his friend’s 10,000-acre ranch in Victoria, Texas. Good got more than a hunt: the friend offered to load up a cattle trailer and send Eurasian wild boar back to a pen Good had set up in Chalmette. Good, now 80 years old, says he intended to transfer the boar to another friend’s private property in Mississippi, “but the majority of them escaped through the fence, and thus populated Verret, and the levee, and New Orleans East.”

“That’s how the Russian boar stock got over here,” Good says. “I hate to say it, but it was me.”

A feral swine with strong Eurasian wild boar features, including dark, coarse fur and prominent tusks. (Photo by Jonathan Kemper on Unsplash)

Though there has been significant interbreeding with feral hog populations at this point, experts agree that the approximately 17 Eurasian wild boar Good brought into Chalmette in 1973 account for essentially all the Eurasian wild boar and related hybrids in Louisiana today, most of which can be found in the marshes east of New Orleans East. According to Good, though, the escapees initially disappeared into the swamp for a few years before a dirt biker tipped him off to seeing them on levees in New Orleans East. Rather than eradicate them, Good and a small group of fellow sportsmen decided to form an organization called the Wild Boar Conservation Association (WBCA) that advocated for preserving wild boar populations for the purpose of hunting them on private property. “We really had no idea, the numbers,” Good says. “But what we had, we felt like we ought to try to keep, so we could continue hunting and not let the other shooters that weren’t in the club go out and slaughter them.”

The Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (LDWF) did, however, seem to know they had an emergent problem on their hands. In 1986 the Alexandria Daily Town Talk published a profile of Good and the WBCA that included something of a disclaimer from LDWF: “Where wild hogs are found on wildlife management areas, hogs may be taken during any legal hunting season and removal is encouraged because biologists do not think hogs are compatible with the habitat or native animals. There are no regulations preventing stocking of wild hogs on private lands, but releasing them on state-owned or other open lands would be frowned upon.”

At that time, a significant portion of the marshes in eastern Orleans Parish were privately owned, and Good, a licensed pilot, helped NOPD patrol the area for poachers via helicopter. The area had long been marked for the continued expansion of New Orleans East, but a combination of factors contributed to those plans being abandoned. Developed in the style of a suburb within city limits, New Orleans East had become a haven for mostly white residents fleeing the urban core of the city in the 1960s and ’70s. The oil bust of the mid-1980s dimmed hopes for further development, however, while an influx of new Black residents and Vietnamese immigrants following the end of the Vietnam War precipitated white flight out of the East.

Against this shift in demographics and economics in the area, 19,000 acres of the land east of the city would soon instead be conveyed to the federal government in a $3 million deal authorized by Congress for the purpose of establishing the Bayou Sauvage National Wildlife Refuge—the first urban wildlife refuge in the country. The deal, which Good says he wasn’t involved in, was approved in 1986, and the refuge opened to the public in 1990. Though hunting is permitted on the refuge now, it wasn’t when it first opened, and the hogs that were already there continued to reproduce.

Apple Seeds

Meanwhile, the outdoor entertainment industry took off, and fueled a surge in enthusiasm for hunting hogs, which became the second-most popular big game animal in North America, after white-tailed deer. “They were seen as very challenging to hunt, even with a hint of danger, very good to eat, and were an impressive trophy,” Mayer says.

More hunters—not just the millionaire class, but still overwhelmingly white—realized they could have the thrill of the hunt on their own private property without having to travel long distances or deal with public land regulations. “People decided, ‘Hey, I don’t want to have to drive to Pearl River or Catahoula Lake Basin—I’ll put some in my pickup truck and put them in this woodlot over here,’” says Jim LaCour, state wildlife veterinarian for the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. “You took an animal that can reproduce exponentially and just planted the seeds like Johnny Appleseed across the state.”

A group of feral hogs, also known as a sounder, gathers near a feeder in Louisiana. These hogs, like most in the wild today, are likely hybrids of Eurasian wild boar and feral hogs originally descended from domestic stock. (Courtesy of Jim LaCour / LDWF)

With state and federal agencies beginning to monitor pig populations more closely, hunters turned to more clandestine means of transporting animals, usually under the cloak of night. “Guys would load stock trailers full of wild hogs, pull a remote-control door on a road, turn the lights off, and turn them all loose,” says Goatcher, who worked for the US Fish and Wildlife Service for 18 years before retiring to do nuisance wildlife contract work. “That was common back then.”

Trapper John admits to partaking in the hog trade. “I trapped wild boar and sold them to people across the country, so they could stock wild pigs around,” he says. “Back then it was very popular.”

Releasing feral hogs into the wild has been illegal for decades, however, and a certificate of veterinary inspection and testing for common diseases for hogs being transported across state lines has been mandated since at least the 1950s, LaCour says. He also notes that the stocking and interstate movement of feral swine has never been legal. Louisiana did allow free-ranging domestic hogs in 14 parishes until 2010, and didn’t begin limiting the transportation of feral swine within the state until 2016. The Department of Agriculture and Forestry now issues permits, and feral swine can only be moved to approved holding facilities, of which there are currently 81 in the state. The department says it hasn’t received a request to transport feral swine across state lines in the last three years. With feral swine now documented throughout Louisiana and in at least 44 other states, though, the hogs no longer need much help from humans claiming new territory.

The Battlefront

Hunters may not be allowed to spread hogs at will anymore, but hurricanes have proven to be just as effective. “The pigs swim like fish, and they can run right across floating marsh,” Goatcher says. “I’ve seen a hurricane roll up sugarcane like a giant mat, miles wide, and the hogs make tunnels in there. Other animals, even alligators, would freak out and swim and drown or get pummeled. Nothing can knock the hogs back.”

This wild boar is one of several motifs—including a crawfish, an alligator, and pelicans—that appear on this hand-carved cypress mantel by Enrique Alférez. Despite their invasive status, boar have become symbols of the Louisiana wilderness. (THNOC, 1978.204)

LaCour says that the state is routinely falling well short of harvest benchmarks needed to keep numbers in check. Hunters would need to eradicate roughly 75 percent of the population annually, but in recent years the harvest has routinely been below 40 percent. Last year, however, Louisiana hunters took out 625,000 hogs, a spike LaCour says might be a temporary and unusual consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. More people off or out of work might mean more time spent in the wilds hunting.

Other mitigation efforts have fizzled. In 2016 a slaughterhouse in Springfield, Louisiana, became the first and only official purveyor of wild boar meat in the state, with the affiliated Two Run Farm seeking to increase enthusiasm and consumption of wild boar by distributing to restaurants including Carmo and Emeril’s Delmonico. But the operation shut down in 2018, leaving no wild boar slaughterhouses in the state. (Hunters can still dress their own boar, and LDWF offers guidelines for safely preparing the meat.) Poison baiting campaigns have largely been ruled out because of the potential impacts on other species. Brute killing campaigns—including aerial gunning efforts from helicopters—have been deployed, and in 2020 the state passed a new law permitting licensed hunters to kill hogs on private property at night, when the swine tend to be most active.

The matter is a bit more complicated for residents of New Orleans East, because of a longstanding Orleans Parish law against discharging firearms. (The statute lists some areas of exception, largely in the marshes east of the city.) In November WDSU’s Sherman Desselle reported on feral hogs tearing up yards in Oak Island, a neighborhood once envisioned as the first of many eastward expansions of New Orleans East, now isolated between the abandoned Six Flags and the swamp. “A lot of deer and stuff run around here,” says Oak Island resident John Adams. “The hogs run late at night.” They’re used to wildlife in Oak Island, but the increased property damage prompted a number of residents to reach out for help.

These encroachments at the eastern edges of the city might become more common as local experts like LaCour and Goatcher say there’s still plenty of capacity for the hogs to increase their populations and range. The consequence is that the majority-Black residents of New Orleans East have been put on the front lines of a battle they didn’t choose, facing a feral hog nuisance largely exacerbated by the choices of white hunters over the last 40 years. (As recently as 2016, the US Fish and Wildlife Service reported that 97 percent of hunters in the country were white, with Black and Asian Americans combining for less than 1 percent.)

“It’s kind of been left up to the landowners,” Desselle says, “and a lot of them can’t afford to get that remediation.”

After Desselle’s report came out, he says he received a number of calls from local officials and feral hog hunters trying to learn more about the problem in Oak Island. The next day, a hunter came out and gave a trap to the resident that first reported the issue.

“Situations like that remind us that unfortunately people can’t always rely on state and local officials to fix a problem,” Desselle says. “Sometimes the best help somebody can get is from a neighbor.”

Header image: A mid-17th-century etching by Peter Boel depicts dogs attacking a boar during a hunt. (Courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum)