A Confederacy of Dunces, John Kennedy Toole’s novel set in 1960s New Orleans, is one of the city’s most iconic pieces of literature, yet adaptations of the work have been rare. In the 42 years since the book’s release—it was published posthumously in 1980, 17 years after Toole first drafted the novel and 11 years after he committed suicide—several planned film adaptations have fizzled. Full-scale stage adaptations have been rare, starting with a 1984 musical and followed by a 1993 play, produced by the Baton Rouge–based Swine Palace, that toured the state and was later revived. The Historic New Orleans Collection is home to the play’s design history, which comprises a series of costume drawings and set designs acquired in 2012 from artist and production designer Dawn DeDeaux.

Costume drawings by Dawn DeDeaux for the 1993 play adaptation of A Confederacy of Dunces show Darlene (left), a bar girl at the Night of Joy strip club, and Myrna (right), Ignatius’s pen pal who delivers him from New Orleans. (THNOC, acquisition made possible by Mr. and Mrs. R. Hunter Pierson Jr., 2012.0388.8, 2012.0388.13)

The acquisition came about through THNOC’s participation in Prospect.2, the citywide art exposition held in 2011–12. DeDeaux, a featured artist, created a nighttime multimedia art installation based on the book and its themes, which was installed in The Collection’s historic Brulatour Courtyard in the French Quarter. Titled The Goddess Fortuna and Her Dunces in an Effort to Make Sense of It All, the show called forth the book’s whirling, dark absurdism to explore Roman, medieval, and southern history; reflect on post-Katrina life; and recreate costumes and design elements from the 1993 play.

In Toole’s novel, protagonist Ignatius J. Reilly is a misanthropic medievalist who lives at home with his mother in New Orleans. No hero’s journey, the narrative follows Ignatius as he tries and fails to keep a job, rails against humanity in the modern age, and spews judgment and bodily gases at every opportunity. The book situates Ignatius as a maladjusted antihero surrounded by a memorable cast of supporting characters, who revolve around him in a kind of absurdist dance of life. Echoing that revolution is the theme of the wheel of fortune, represented by the Roman goddess Fortuna, with whom Ignatius dialogues in his daydreams.

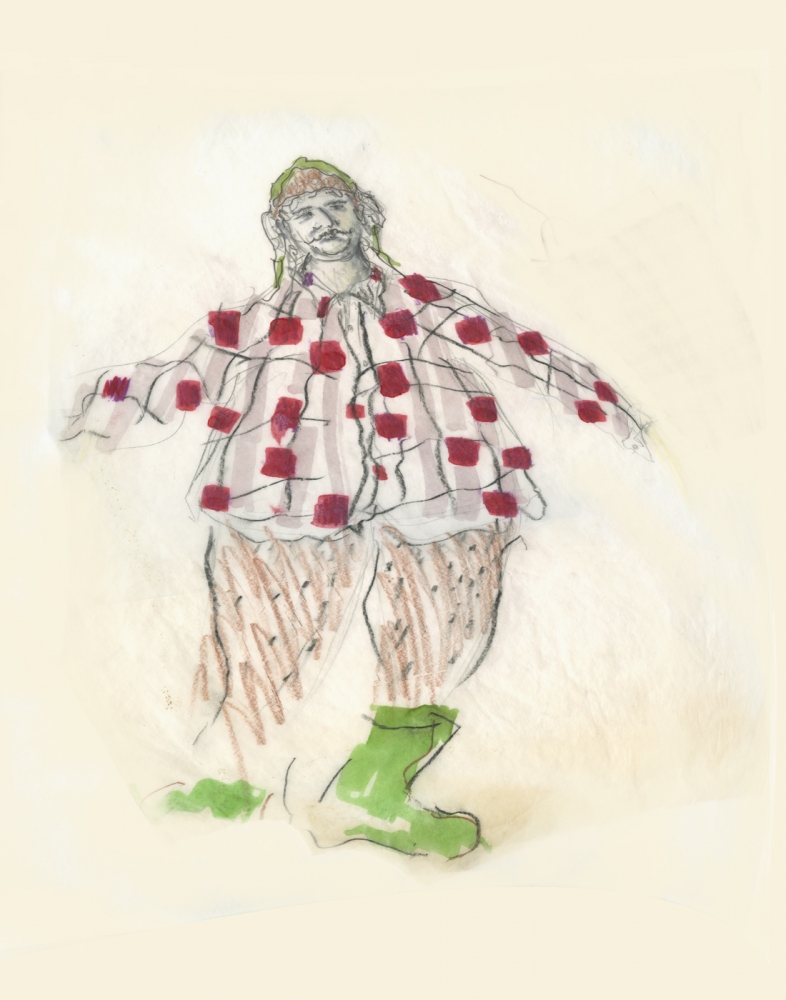

For the Ignatius Reilly costume design, DeDeaux reproduced the signature ensemble described in the book: green hunting cap, baggy shirt and pants, and boots. (THNOC, acquisition made possible by Mr. and Mrs. R. Hunter Pierson Jr., 2012.0388.15)

Translating such an offbeat ensemble piece to film has proved elusive, but for DeDeaux and her cohort, bringing the book to the stage in 1993 was a rewarding challenge. Barry Kyle, who had recently joined the LSU theater department following a career with the Royal Shakespeare Company, directed; his wife, Lucy Maycock, wrote the playscript; and Kyle asked DeDeaux to serve as production designer. DeDeaux had only one other theater credit to her name, but Kyle, who had seen her solo show Soul Shadows at the Contemporary Arts Center, reassured her. “I didn’t think I was the right person,” DeDeaux recalls. “He said, ‘I don’t care. You’re the person. You may not have the theater language, but you have the theater instinct.’”

DeDeaux designed the set, stage, and costumes, drawing on her upbringing in the city to translate the book’s Pulitzer Prize–winning portrait of New Orleans and its people to the stage. “I’m a New Orleanian, and I knew the book well, so I tried to treat the characters as people just down the street, you know,” she says. “Because New Orleans has such a multitude of characters in every neighborhood.”

In this pair of costume designs, DeDeaux captures the comedic, ultimately meaningless transformation of Miss Trixie, the senile senior employee at Levy Pants. Typically she wears a lab coat and visor (“The Standing, Sleeping Miss Trixie Work Coat . . . with White Socks,” left), often falling asleep on the job and wandering around aimlessly. Mrs. Levy gives her a makeover (right) in the hopes of pampering her and convincing her not to retire. (THNOC, acquisition made possible by Mr. and Mrs. R. Hunter Pierson Jr., 2012.0388.5, 2012.0388.2)

Designing Ignatius was simple enough, as clothes are a key component of his character in the book: “He himself is dressed comfortably—in a flannel jacket, baggy pants, and large hunting cap with ear flaps—and regards this as the ideal outfit for a sensible and intellectual person,” Toole writes in the first chapter. The green hunting cap functions as a kind of security blanket for Ignatius and a symbol of his nonconformity; he refuses to take it off throughout the novel.

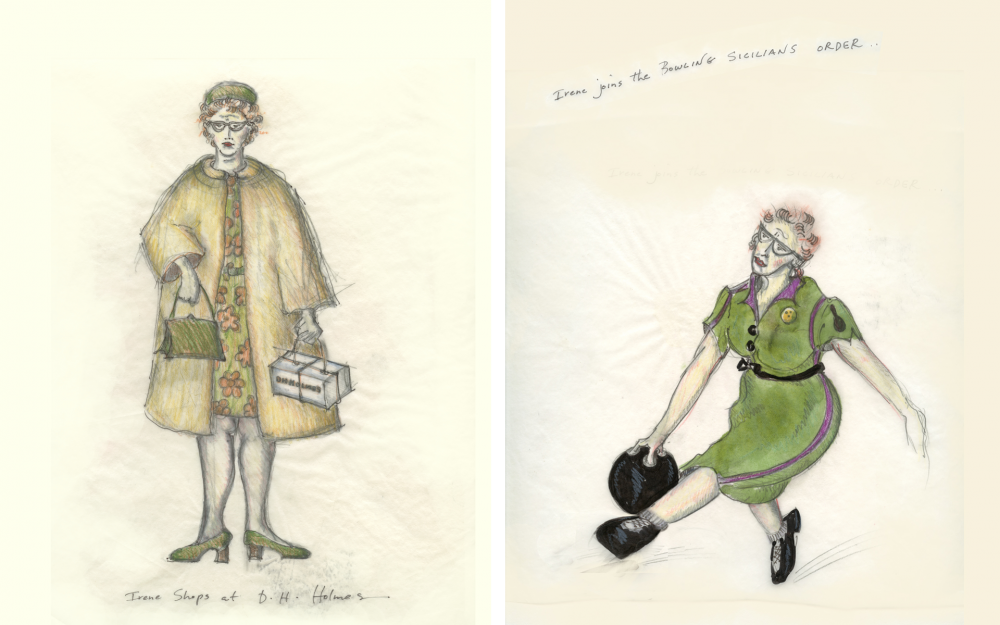

For the character of Irene, Ignatius’s put-upon mother, “That was easy,” DeDeaux says. “I grew up going to Canal Street with my grandmother, in her little white gloves, to D. H. Holmes. We’d shop and get cake in the café.” DeDeaux also knew something of Toole’s own mother, Thelma Toole, whom she had met years earlier through mutual friends. “She was intense,” DeDeaux says. “She had a very high opinion of herself and was very grand in a theatrical way—a lot of fun. She taught elocution, so every roll of a vowel on her tongue was articulated. And she was a fierce defender and champion of her son and his work. Of course, she’s the whole reason the book was finally published.”

DeDeaux was inspired by her own Canal Street shopping excursions with her grandmother for the design titled “Irene Shops at D. H. Holmes” (left). In “Irene Joins the Bowling Sicilians Order” (right), the character’s fashion evolves, seen in this snappy belted dress. (THNOC, acquisition made possible by Mr. and Mrs. R. Hunter Pierson Jr., 2012.0388.6, 2012.0388.19)

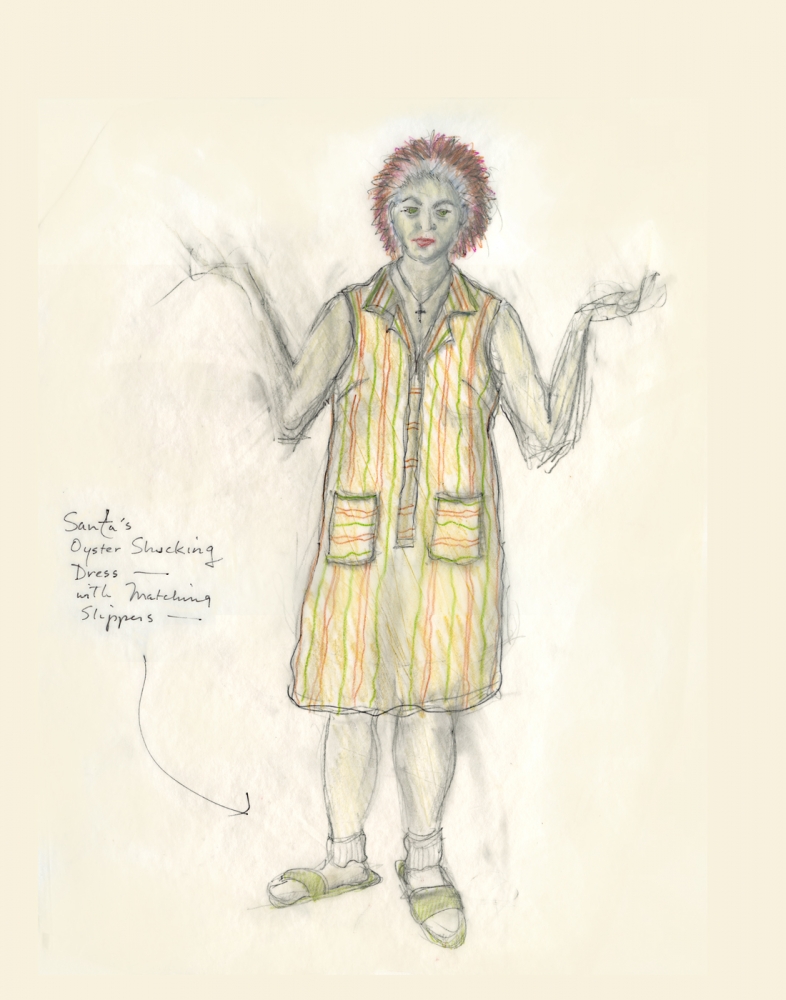

DeDeaux browsed thrift shops for articles and ideas to suit the book’s 1960s setting. One such find, a striped housedress-type shift, became the basis of her design for Santa Battaglia, Irene’s brassy, Italian American friend.

In “Santa’s Oyster Shucking Dress—with Matching Slippers,” DeDeaux depicts Santa Battaglia with a crucifix necklace and devil-may-care stance. (THNOC, acquisition made possible by Mr. and Mrs. R. Hunter Pierson Jr., 2012.0388.17)

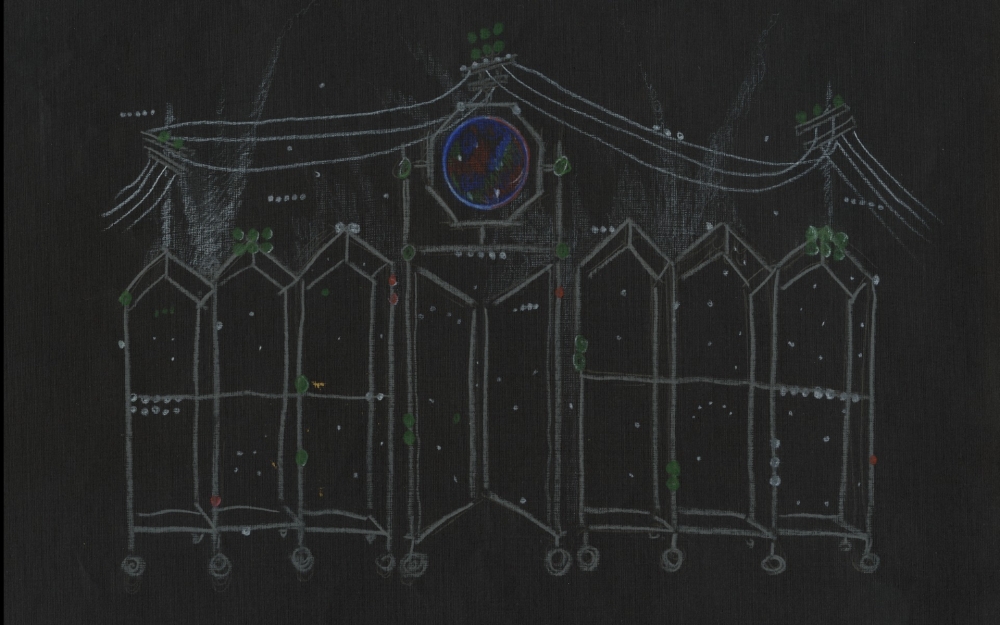

DeDeaux also drew from history, particularly in designing the set. “[Ignatius] didn’t want to face the modern world,” she says. “He lived in this medieval structure in his mind; that’s what he liked. So he was trapped between these two worlds.” DeDeaux materialized the world of Ignatius’s mind, employing Gothic arches centered on a large orb—the wheel of fortune. Stagehands, dressed as medieval dunces in conical hats, changed out the set pieces onstage.

DeDeaux’s design for the rear stage set features Gothic arches, power lines strung like bunting, and a blue orb in the center—the wheel of fortune. (Courtesy of Dawn DeDeaux)

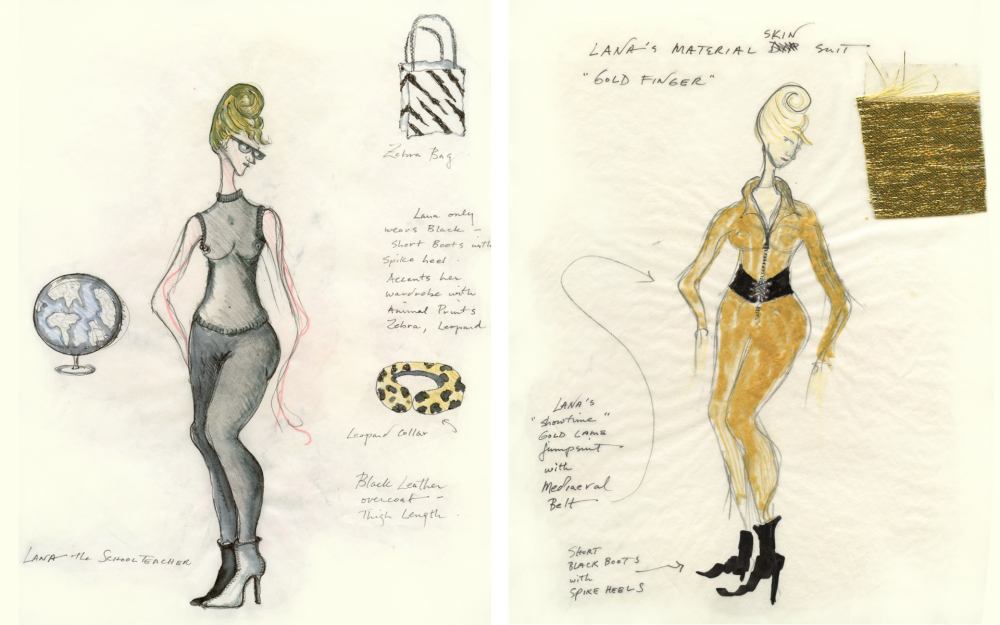

For the character of Lana Lee, the shady owner of the Night of Joy strip club, DeDeaux borrowed from mod fashion, dressing her in tight black pants and a sheer sleeveless mock turtleneck, with a beehive updo. Burma Jones, the Night of Joy’s underpaid, subversive African American janitor, wears black gloves—a nod to the Black Panther movement of the 1960s, DeDeaux said.

“Lana the School Teacher” (left) puts the Night of Joy strip club owner in a sexy mod style. In “Lana’s Material Skin Suit ‘Goldfinger’” (right), DeDeaux accessorizes the costume with spike-heeled black boots and a corset-like “medieval” belt. (THNOC, acquisition made possible by Mr. and Mrs. R. Hunter Pierson Jr., 2012.0388.20, 2012.0388.14)

DeDeaux and Kyle began working on the Dunces production in late 1991, and in September 1993 the play opened at the LSU Theatre in Baton Rouge, where it enjoyed a solid run. DeDeaux’s “larger-than-life” stage design earned special mention in the Baton Rouge Advocate’s review, as did the lead performance by John “Spud” McConnell, who became so known for the role that in 1996 he served as the model for a life-size statue of Ignatius Reilly that still stands on Canal Street.

When DeDeaux returned to the realm of Dunces nearly 20 years later with The Goddess Fortuna and Her Dunces in an Effort to Make Sense of It All for Prospect.2, she transformed THNOC’s Brulatour Courtyard into Ignatius’s bedroom and inner sanctum. Visions of the goddess Fortuna, portrayed by bounce artists Katey Redd and Big Freedia, were projected on the courtyard walls.

DeDeaux’s rendering of her 2011–12 Prospect.2 installation shows the Brulatour Coutyard transformed into a Confederacy of Dunces dreamscape. Her original costume design for Ignatius is seen at right, with hot dog cart, and a row of medieval dunces watches from the balconies above. (Courtesy of Dawn DeDeaux)

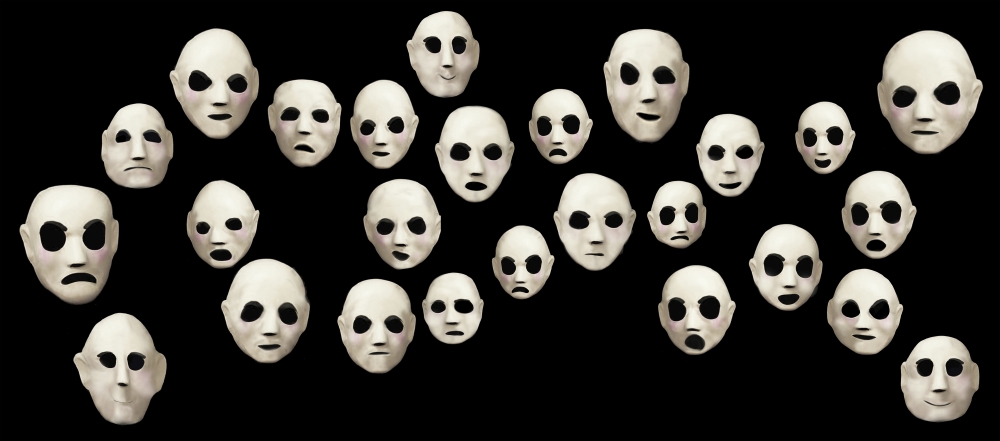

From the upper windows and balconies of the buildings surrounding the courtyard a host of medieval dunce sculptures looked down on the proceedings. The dunce’s caps, she says, were intentional references to the Ku Klux Klan and the double entendre of the book’s titular confederacy. (The phrase “a confederacy of dunces” comes from 18th-century satirist Jonathan Swift, but it also refers to the Confederacy of the American South and, by extension, to the idea of sedition.) The Klan’s connection to Mardi Gras—“the dark side of the frivolity,” DeDeaux says—was represented in a motif of haunting white masks made to resemble those worn by masked Carnival krewes.

DeDeaux conceived of the mask motif in her Goddess Fortuna installation as a nod to the intertwined histories of white supremacy of Carnival krewes—vestiges of the Confederacy hidden behind a mask of frivolity. (Courtesy of Dawn DeDeaux)

When DeDeaux began working on the show, in 2010, New Orleans was still finding its way after Hurricane Katrina, and a massive earthquake in Haiti had just killed roughly a quarter million people. “Things were helter-skelter,” DeDeaux says. “I said, ‘When disasters like this keep happening, you can only turn to the goddess Fortuna.’”

Banner image: Production design drawing by Dawn DeDeaux for her 2011–12 installation The Goddess Fortuna and Her Dunces in an Effort to Make Sense of It All, depicting a component she calls the “Levy Pants Factory Procession” (THNOC, acquisition made possible by Mr. and Mrs. R. Hunter Pierson Jr., 2012.0388.25)