Storyville was New Orleans’s legal red-light district that operated between 1898 and 1917. For most of its brief existence, visitors to the District, as it was known, could navigate the neighborhood and its services with the help of special guidebooks that contained directories of sex workers listed by name, address, and race, as well as advertisements for individual establishments and luxury products.

The most famous of these guides are editions of a publication titled Blue Book, which was compiled by William Struve under the pseudonym Billy News. A former police reporter for the New Orleans Item, Struve was a close friend and associate of Thomas C. “Tom” Anderson, an entrepreneur, a state legislator, and the so-called Mayor of Storyville. New Orleans was not the first, nor the only, city whose vice district had its own guides, but blue books were probably produced more regularly than other cities’ prostitution guides.

In this story, THNOC Senior Librarian and Rare Books Curator Pamela D. Arceneaux highlights nine of the blue books’ most interesting aspects, based on her thorough study of them in Guidebooks to Sin: The Blue Books of Storyville, New Orleans, published by THNOC in 2017. For more on Storyville itself, visit THNOC's new virtual exhibition Storyville: Madams and Music.

While you read, listen to our Spotify playlist “Storyville,” assembled by Curator/Historian Eric Seiferth.

1. Target audience: the affluent white male tourist

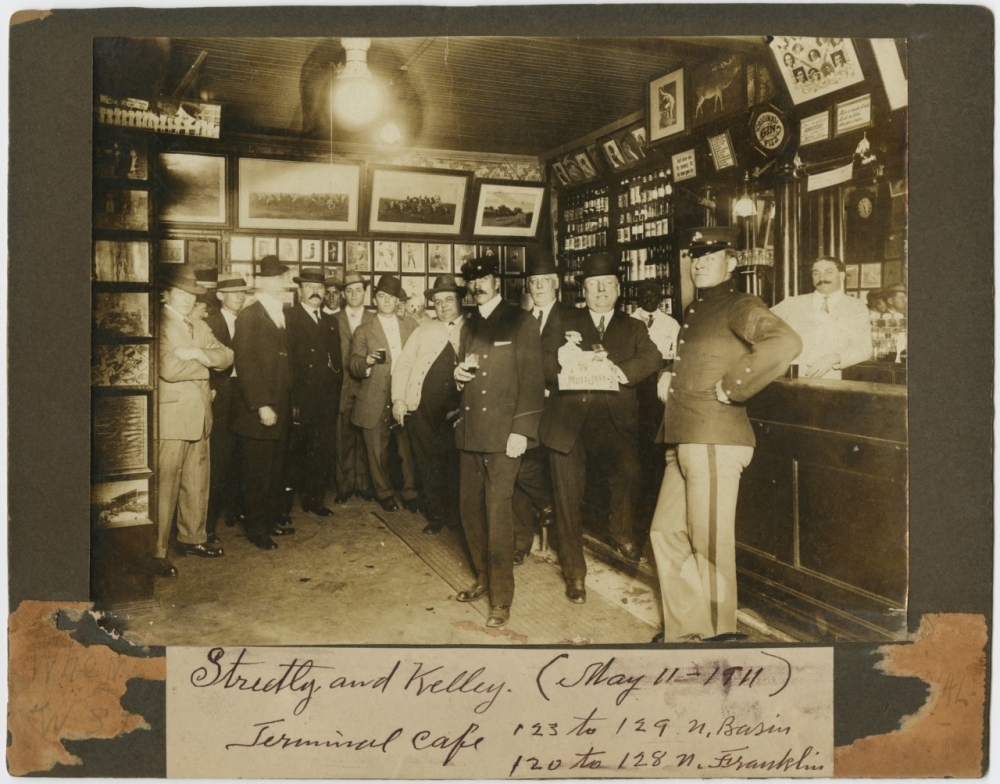

A group of men is pictured at the Terminal Café in Storyville. (THNOC, 2000.80.5)

Like any advertising medium, the blue books were designed for a particular audience, and Storyville flourished alongside the rise of consumerism in the United States. These guides to the sporting scene—filled with sex, fraternal camaraderie, drinking, and gambling in New Orleans’s male tourist mecca—sold to their readers a dreamlike world of prostitution ensconced in high-class style and elite access. They referred to the reader as a man-about-town who was, in euphemistic terminology, “out on a lark.” The term “blue book” itself harks back to guides of prominent blue bloods, establishing the reader as a well-heeled, white man.

Blue Book was sold where men congregated—in barbershops, saloons, hotels, and railroad stations, and an evening out in Storyville was more than simply a visit to a brothel. At the turn of the 20th century, New Orleans was in a push to increase tourism in its otherwise lackluster economy, and Storyville’s bustling saloons, beer halls, and clubs made it one of the city’s main entertainment districts.

2. They make (almost) no mention of sex.

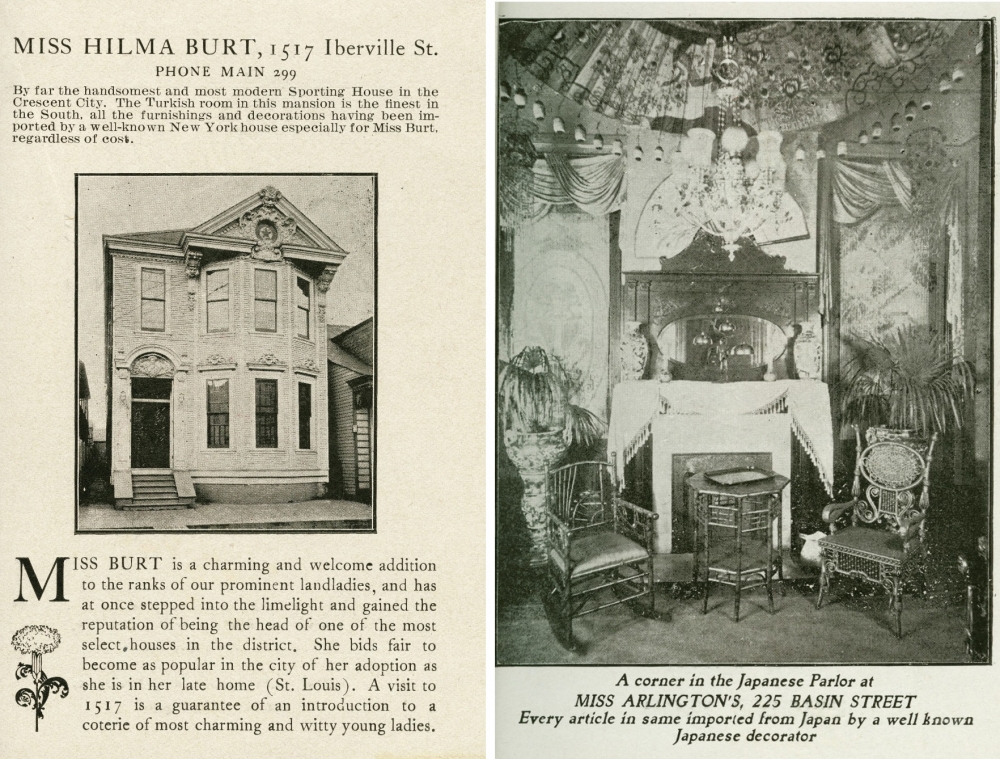

Two pages from separate editions of Blue Book show how flowery language and photography were used to sell sex in Storyville. (THNOC, 1969.19.7; THNOC, 1969.19.6)

In most instances, the madams’ full-page advertisements in the blue books provide little real information about the sex workers in their employ and almost no physical descriptions. Promoting the pleasures of wine, women, and song in florid language meant to amuse the reader, the advertisements for the more highly regarded brothels are suggestive rather than explicit, written in relatively demure terms. Every madam or landlady is glorified as a queen among queens, keeping the most elaborate and costly establishment—almost to the point of self-parody. In fact, many of the ads used interchangable language—sometimes ads on facing pages featured near identical copy—and were likely written by Struve. The only innuendo the blue books make is “French” or “69” when referring to fellatio. Fake guides that were produced decades later, capitalizing off of the notoriety of the real blue books, would include more explicit descriptions.

Blue books marketed a fantasy of sex—glamorous, exotic, and taboo—but most of the women listed in their directory pages lived and worked in Storyville’s lower-class houses or operated semi-independently; their reality was neither glamorous nor exotic. Except for a few top-of-the-line sporting palaces, mainly clustered along or near Basin Street, most of the District’s houses were unpretentious.

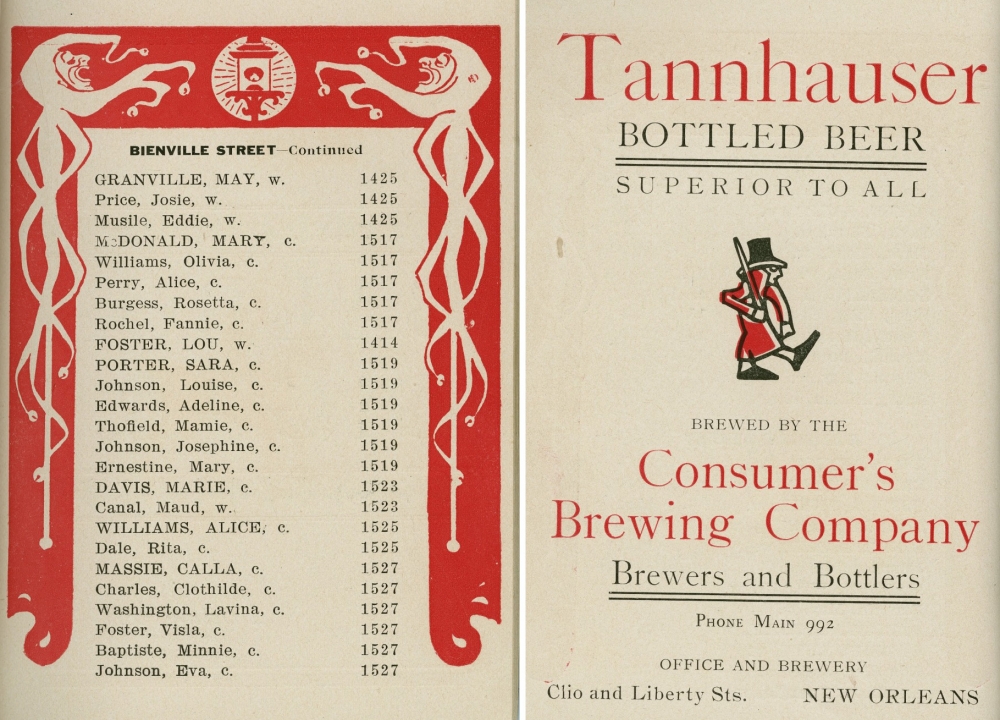

3. Women are listed by race, for the white male consumer.

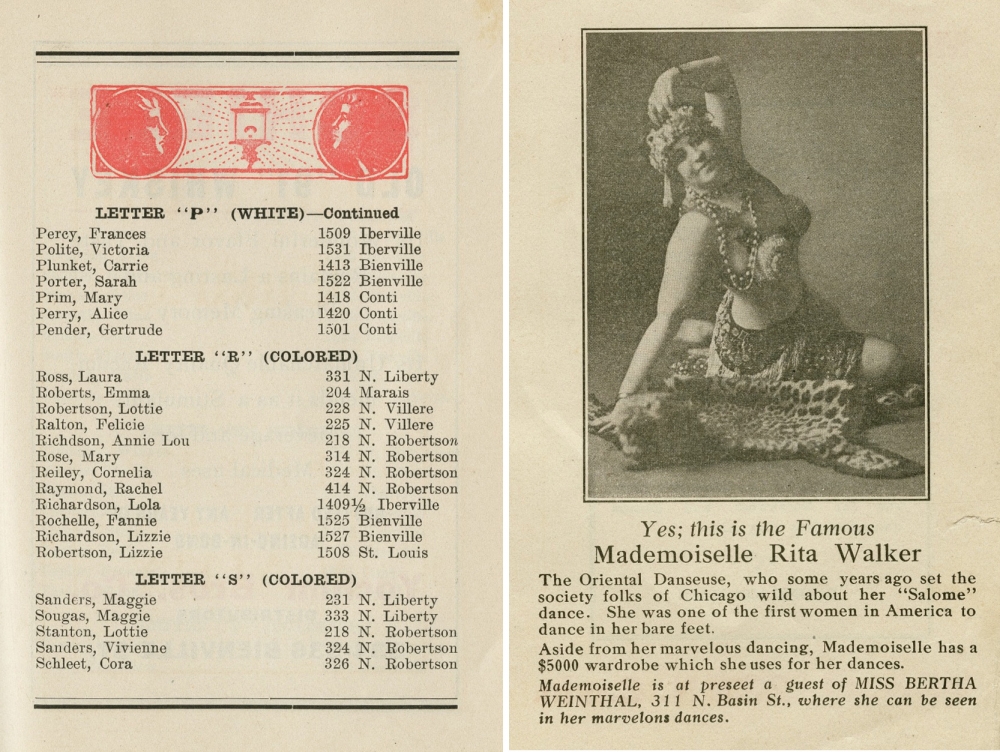

A directory page (left) lists names of sex workers according to their race. In the same edition, an advertisement (right) shows the exoticism used to market sex with women of different races. (THNOC, 85-517-RL)

Storyville’s attractions were only available to white men, but throughout its run, a separate district further uptown existed for black patrons; however, in practice some racial intermingling was tolerated in both areas. No known guides exist for so-called Black Storyville. For their white male audience, blue books offered access to sexually taboo attractions, most visibly the promise of sex with mixed-race women, or “octoroons.” White men were eager to recreate the antebellum dynamic in which enslavers held power over light-skinned black women. The madams of Storyville, many of whom were black, played into this dynamic with elaborate brothels, called “octoroon houses,” that catered solely to these interracial fantasies.

At the time, another myth circulated that Jewish women, especially those having red hair, were extremely passionate, and some editions note the availability of Jewish prostitutes in Storyville. Fascination with the exotic shaped by racial tropes—particularly the orientalist notion of the mysterious sensuality of the East—is a recurring subtext of the blue books.

4. You weren’t allowed to mail them.

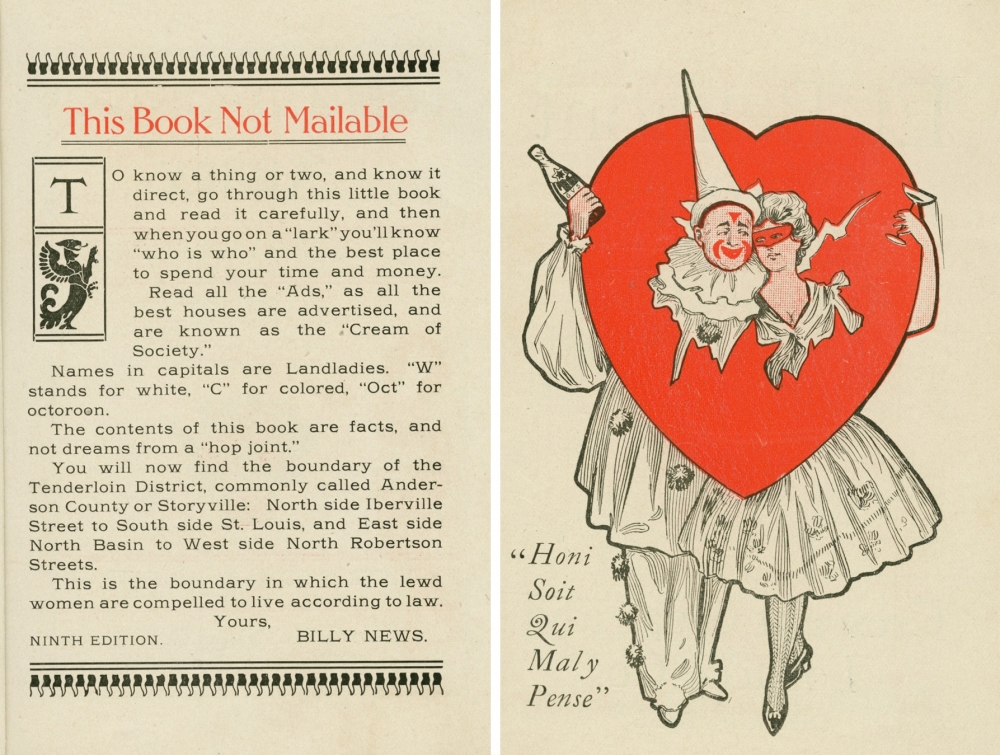

This circa-1908 edition of Blue Book warns readers against mailing it. This edition also includes an embellished illustration with the phrase “Honi Soit Qui Mal y Pense” (“Shame on he who thinks evil of it”), which was used throughout Blue Book’s run. (THNOC, 1969.19.9)

Nearly all editions of Blue Book contain a warning that the compact guides cannot be mailed. The Comstock Law, passed by Congress in 1873, made it a crime to sell or distribute materials through the United States Postal Service that could be construed as corrupting to public morals. Named for its most vigorous proponent, Anthony Comstock (1844–1915), lobbyist for moral reform and head of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, the law prohibited mailing information about birth control, abortion, sexuality, or sexually transmitted diseases, or literature considered obscene or pornographic. In promoting the sale of carnal pleasure, Blue Book certainly fell under this description.

5. The Storyville residents they don’t mention

A 1930s photograph shows a building that housed one- or two-room structures, known as "cribs," when Storyville was active. (THNOC, gift of F. Lee Eiseman, 1990.2.7)

In marketing the promise of erotic adventures among the elite entertainers of New Orleans’s fabulous Storyville, the District’s promoters were not interested in including prostitutes who did not contribute to the desired glamorous image. Therefore, there were many sex workers in the District who weren’t listed in its pages, like the women who worked in “cribs,” crude one- or two-room structures, or larger buildings partitioned into small spaces. There, women worked in shifts under terrible conditions. These were the only places where black men could hire prostitutes in Storyville.

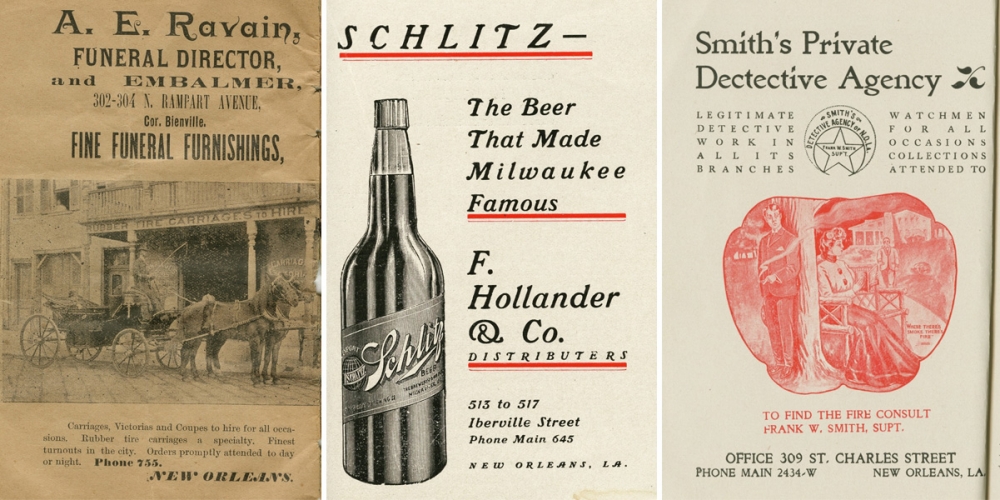

6. Familiar brands in the advertisements—and some strange outliers

An early edition included an advertisement for a funeral director, and a few years later, national brands like Schlitz advertised alongside local services like Smith’s Private Detective Agency. (THNOC, 94-092-RL; THNOC, 1969.19.7)

Since most of the ads address the needs and desires of men out for an evening of wine, women, and song in the red-light district, it is not surprising that, by far, the majority of advertisements are for alcoholic potables—liquor, champagne, and beer. Many of the brands advertised in Blue Book are still available, while others have faded away. Liquor brands still in existence today include Dewar’s, Veuve Clicquot, and Budweiser, among many others.

Among the lesser-known advertisers were local services like cigar shops, glass cutters, saloon keepers, and a funeral director, who offered carriages out for hire. There were also plentiful mentions of medical treatments for those suffering with sexually transmitted ailments, like "crawlers" or "gleet." And in one edition, there’s even an ad for a private detective service.

7. Their avant-garde printing and design

This 1907 edition of Blue Book uses popular design features such as rubrication (left) and graphics known as Mission Toys (right). (THNOC, 1969.19.8)

Early editions of Blue Book were made using cheap paper on a letterpress printer and were probably produced by a local printer or stationer, or by any number of local newspapers. Because of their ephemeral nature, the books were intended to be discarded after their use, which is one reason that so few copies remain. In 1903, as more revenue from advertisers became available, editions began sporting more expensive-looking and durable calendered paper, an effect most likely achieved via the emerging cost-efficient printing technologies of the day. Another printing feature called rubrication emphasized words, phrases, and design elements with red ink. Often seen in medieval texts, rubrication had been enjoying a revival among avant-garde designers and publishers of some arts and literary magazines of the 1890s.

Some later editions of Blue Book were randomly embellished with bold, whimsical figures and abstract designs called Mission Toys, products of the arts and crafts movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It is interesting to note that nearly as soon as they were made available to printers, these Mission Toys began appearing in the pages of a New Orleans brothel guide.

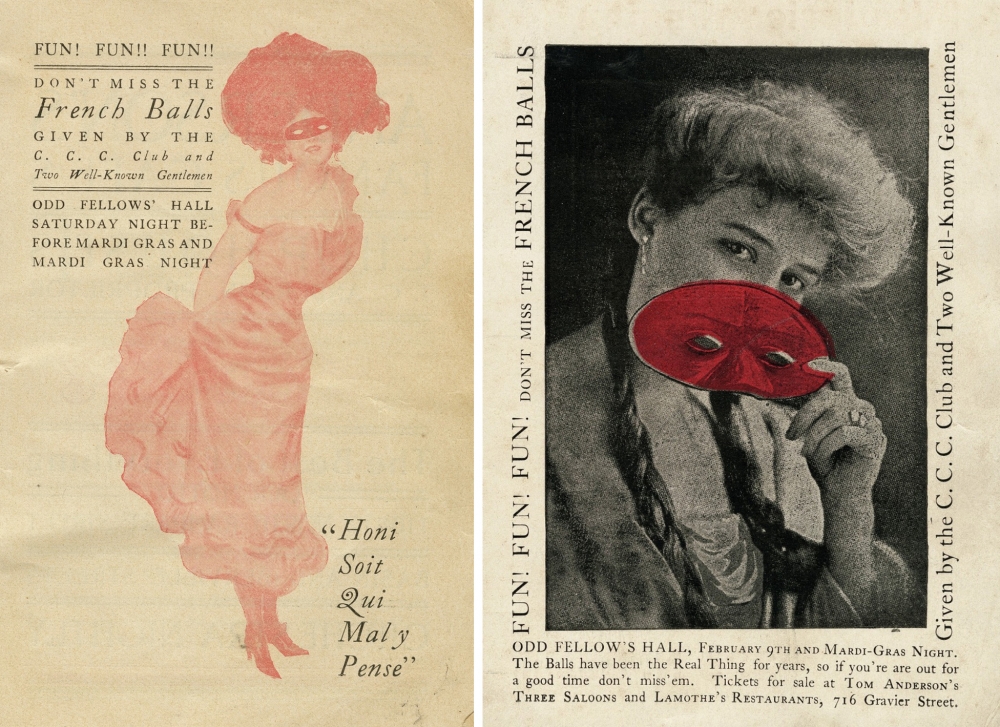

8. They were likely distributed around Mardi Gras.

Promotions for the "French" Mardi Gras balls are shown in two different editions of Blue Book. (THNOC, 1969.19.8; THNOC, 2012.0141.1)

Given that Storyville was a tourist attraction, and that New Orleans’s largest tourist draw has long been Mardi Gras, these guides were likely distributed during the Carnival season. Advertisements for special balls make this clearer. Described as “French” to indicate their bawdy nature, these parties were held during the Carnival season, organized by Storyville’s business owners, and attended by madams, prostitutes, and the men who frequented the District. Many editions of Blue Book contain advertisements and dates for them. The best-known were those given by the CCC Club, always held on the Saturday evening prior to Mardi Gras, and by the Two Well-Known Gentlemen, always held on Mardi Gras night.

9. The soundtrack of the District

Tony Jackson (left) and Ann Cook (right) both played piano in Storyville brothels. Piano “professors” were considered the most skilled musicians in the District. (The William Russell Jazz Collection at THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 92-48-L.241 and 92-48-L.276)

Tony Jackson (left) and Ann Cook (right) both played piano in Storyville brothels. Piano “professors” were considered the most skilled musicians in the District. (The William Russell Jazz Collection at THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 92-48-L.241 and 92-48-L.276)

The ubiquitous nature of music within the District is apparent in Storyville’s guidebooks. Madams’ advertisements regularly emphasized the musical offerings of their establishments, and the last known edition of Blue Book, the most often seen of the District’s guidebooks, includes a list of nine cabarets. The best brothels featured musicians, typically small string ensembles or piano players—the latter known as “professors,” who were the highest-earning musicians in the District, bringing in significant nightly tips. Establishments with fewer resources might have a coin-operated mechanical player piano or a hand-cranked gramophone.

The District’s musical offerings contributed to the neighborhood’s allure as an entertainment mecca. Visitors could choose nightly from a range of establishments based on the sounds, dances, prices, and clientele they preferred. Many of the clubs operated as “black and tans”—some run by African Americans—where integrated audiences were tolerated by law enforcement and many whites eagerly consumed black culture.

Curator/Historian Eric Seiferth contributed information about the music of Storyville to this story. For more on Storyville's music, visit THNOC's virtual exhibition Storyville: Madams and Music.

For more on the blue books, read Pamela D. Arceneaux's Guidebooks to Sin (available from The Shop at The Collection), and visit THNOC's virtual exhibition Storyville: Madams and Music.

For more on the blue books, read Pamela D. Arceneaux's Guidebooks to Sin (available from The Shop at The Collection), and visit THNOC's virtual exhibition Storyville: Madams and Music.