In the mid-20th century, nutria were seen as a valued, if pesky, member of Louisiana’s wildlife family.

Fur traders brought the South American species to Louisiana in the 1930s, where the semiaquatic rodent joined mink and muskrat as part of the state's trapping industry. A 1959 report issued by the Louisiana Wild Life and Fisheries Commission, now known as the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, acknowledged that the “voracious and prolific vegetarian” was known to feast on rice and sugarcane crops and posed a threat to levees with its practice of burrowing tunnels. However, the report argued, the nutria (Myocastor coypus, described as an “overgrown guinea pig, with a rat’s tail”) formed an important part of the state economy.

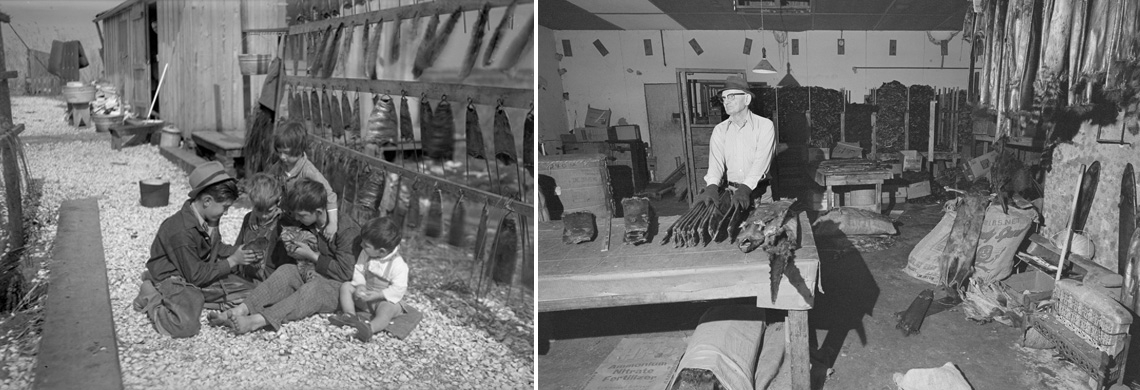

A group of boys hold a nutria and a cat in this circa 1940 image, with nutria pelts drying in the background. (THNOC, gift of Joel Jergins and Mrs. Eugene Delcroix, courtesy of the New Orleans Museum of Art, 1984.189.57)

Trappers had pulled in a half million pelts in the 1957–58 season, up from approximately 78,400 seven years prior (more than a 500% increase). Though prices had taken a recent dip, opportunities for trappers and tanners were still plentiful: the furs supplied material for coats and coat linings, and the carcasses could be sold for dog and mink food.

By the 1980s, however, the nutria had become a full-blown scourge. Over the decade prior, demand for fur plummeted. According to the state’s Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, fur fell out of fashion in many parts of the world, owing in part to the animal-rights movement. Concurrent with the drop in demand was a boom in Louisiana’s oil and natural-gas industries, which offered better and steadier wages than did trapping. Many of the state’s tanneries and trappers had moved on to other prospects. The nutria population surged, threatening coastal wetlands because of the animal’s practice of tearing up grasses at the root and damaging levees and roadways with its tunnels.

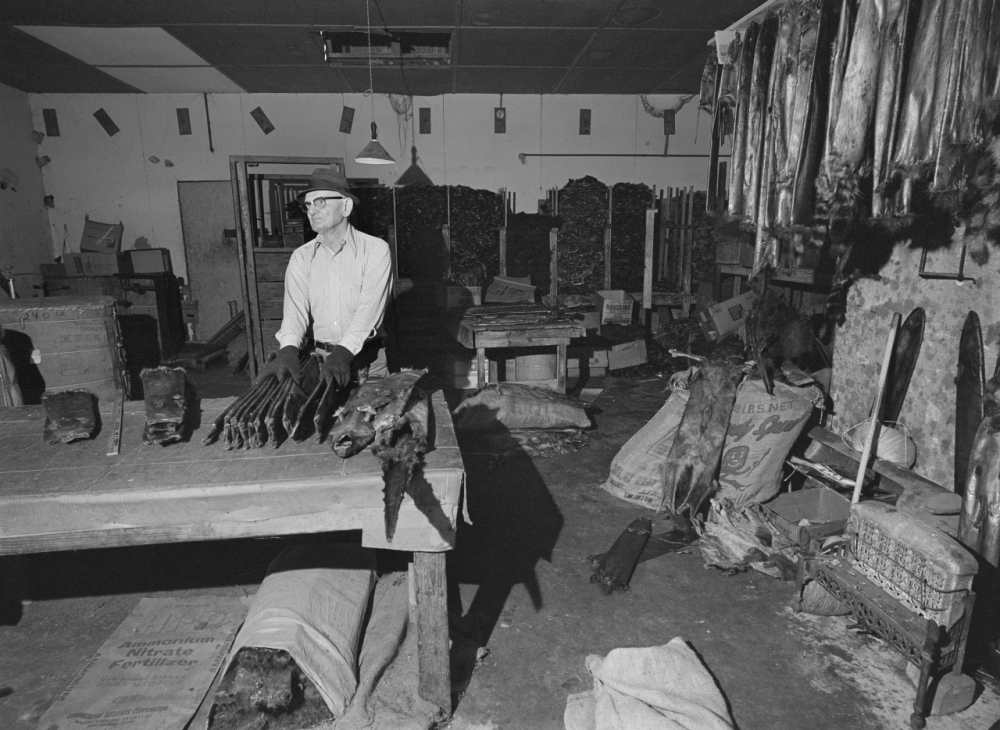

A man is pictured with nutria pelts in this photo taken by Douglas Baz and Charles H. Traub at Sagrera and Son Fur Dealers in Abbeville, Louisiana, in the early 1970s. (THNOC, ©Douglas Baz and Charles H. Traub, 2019.0362.58.1)

So began, in 2002, the campaign to mitigate the orange-toothed rodent of unusual size (10 to 18 pounds on average). Trappers became bounty hunters, and today the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries offers $6 per tail to encourage nutria-population control.

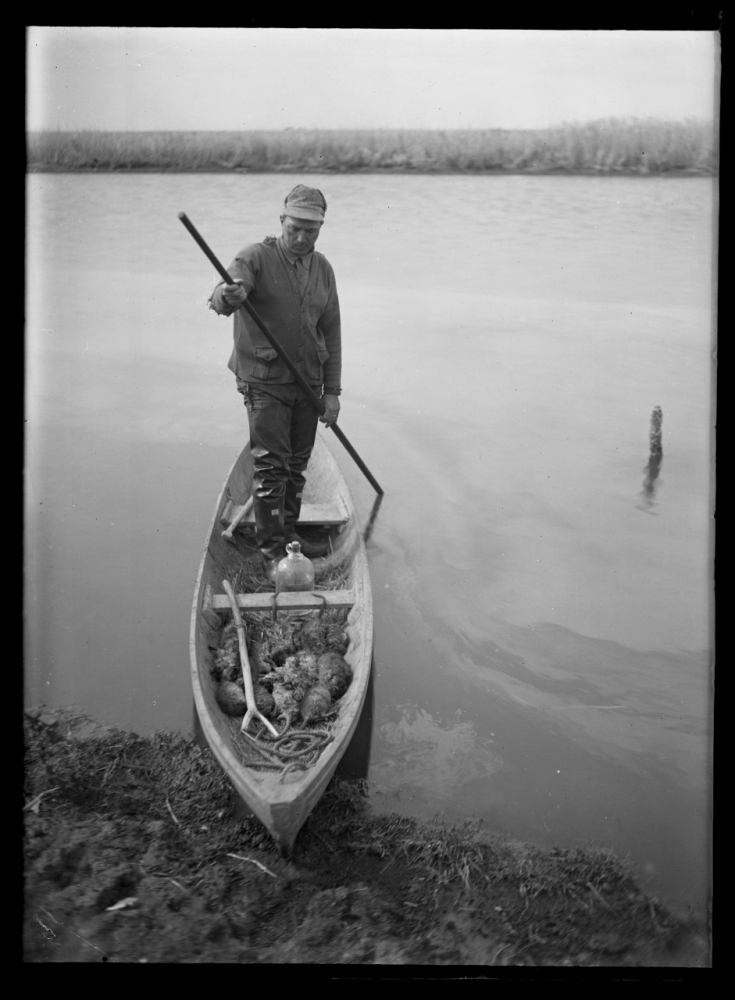

A man is pictured in this mid-20th century image with a pirogue full of nutria. (THNOC, gift of Joel Jergins and Mrs. Eugene Delcroix, courtesy of the New Orleans Museum of Art, 1984.189.4136)

Law enforcement were tasked with shooting nutria as part of their routine duties, reaching a dramatic peak in the mid-1990s with Jefferson Parish Sheriff Harry Lee’s campaign to decimate the 9,000-plus population that was overtaking the area’s drainage canals. Smaller and less-successful efforts included attempts to market nutria meat for human consumption.

Nutria for Home Use, by Leslie L. Glasgow and Lavon A. McCollough was released in 1963 and included recipes for nutria gumbo, macaroni-nutria casserole, and nutria chop suey. (THNOC, 98-083-RL)

A 1963 cookbook published by Louisiana State University offered recipes for nutria gumbo, macaroni-nutria casserole, and nutria chop suey. In recent years, the artist Cree McCree, through her Righteous Fur fashion line, has sought to reframe nutria fur and jewelry as an eco-friendly, wetlands-assisting choice.