Sports captivate us with narratives of improbable upsets, great champions, and bitter rivalries. Sometimes the story extends beyond the field of play, instigating or mirroring broader social, economic, and cultural change. These moments endure. They shape our community identity.

Here in New Orleans, the evolution of organized sports over the last 150 years has paralleled the fundamental transformations brought to the city after the Civil War. Sports became an important instrument for challenging the city’s resistance to gender equality and racial integration for much of this era, and also created opportunities for New Orleans to become a leading tourist destination.

THNOC's 2020 exhibition Crescent City Sport: Stories of Courage and Change explored athletic moments that illustrate New Orleans’s evolution over this time period. Five stories below recall some lesser-known narratives that remind us how interesting and important sports can be.

1. Backwoods bare-knuckle boxing matches

A photograph shows the seventh of 75 rounds in John L. Sullivan’s bout with Jake Kilrain. The illegal bare-knuckle match resulted in arrests for both fighters. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

During the 1880s and ’90s New Orleans was at the center of the sporting world thanks in large part to prizefighter John L. Sullivan, the “Boston Strong Boy.” Most states prohibited prizefighting in the early 1880s—and though the Deep South was no exception, the region had a reputation for looking the other way when such laws were broken. In February 1882, far-flung journalists and well-heeled fight fans, some of ill repute, descended upon New Orleans in anticipation of a bare-knuckle bout—at an undisclosed location outside city limits—between the 23-year-old Sullivan and world champion Paddy Ryan. On the morning of February 7, the crowd boarded a train bound for the Barnes Hotel in Mississippi City, now part of Gulfport, where a throng of about 1,500 spectators watched the Boston Strong Boy claim the heavyweight title.

Sullivan emerged as one of the nation’s first sports superstars and followed up the Ryan fight with a series of lucrative barnstorming tours, becoming a bona fide celebrity along the way. He traveled to New Orleans again in the summer of 1889 and successfully defended his title at a lumber mill near Hattiesburg in an epic 75-round match with Jake Kilrain. The illegal fight led to arrests for both fighters, compelling Sullivan to vow never to fight bare knuckle again, essentially concluding a brutal era for the sport. James Corbett finally put an end to Sullivan’s reign in a legal match with gloves at the Olympic Club in New Orleans on September 7, 1892. Sullivan’s fights in and around New Orleans made the city, in the eyes of many throughout the nation, synonymous with big-time sporting events.

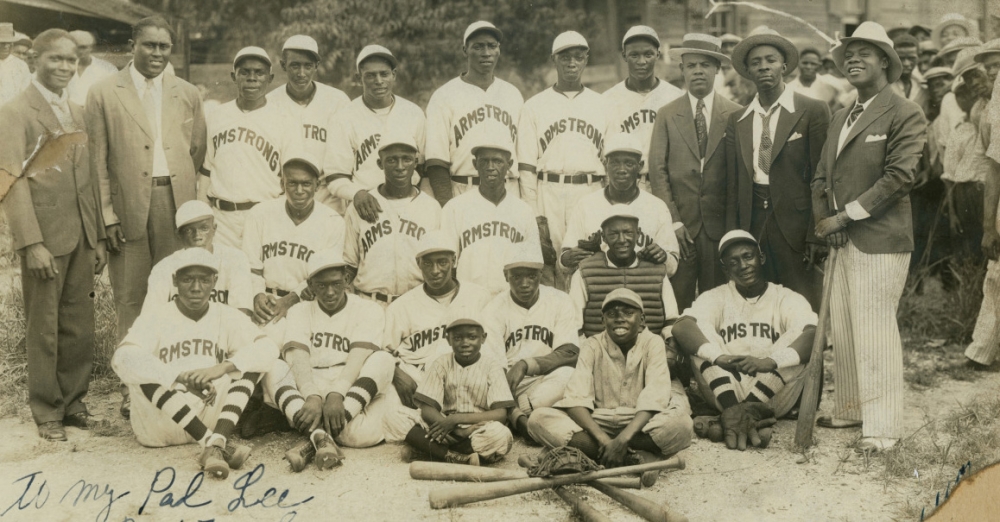

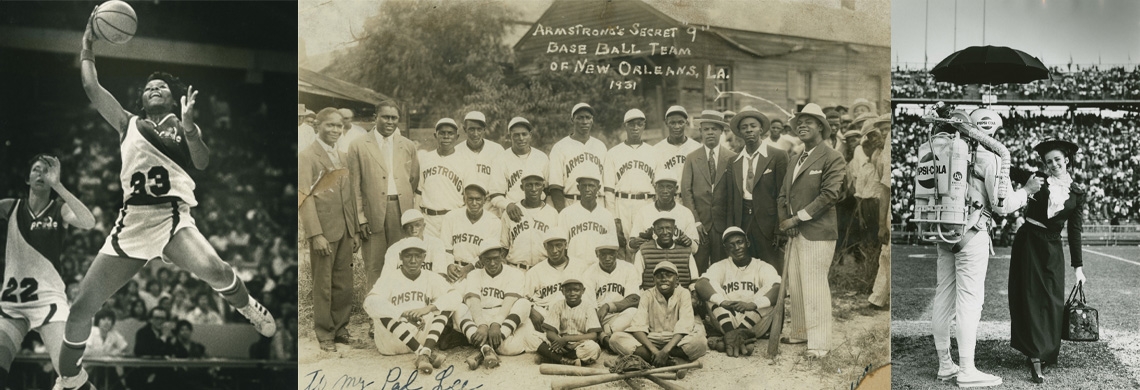

2. Louis Armstrong's Secret Nine

Louis Armstrong’s “Secret Nine” baseball team was known for their pristine uniforms and lackluster play. (The William Russell Jazz Collection at THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 92-48-L.385.358)

Louis Armstrong avidly followed baseball and supported the sport in his hometown by sponsoring his own team in 1931, the Secret Nine. The local papers poked fun at the team for being the best dressed—thanks to Armstrong’s generosity—but not the most skilled. Though they didn’t play in the Negro Southern League, the most prominent association of black ball clubs in the region, they competed against other African American clubs in the city. In August 1931, Armstrong attended a doubleheader at St. Raymond Park in New Orleans, which featured his Secret Nine vs. the Melpomene White Sox in the opener and the Metairie Pelicans vs. the St. Raymond Giants in the nightcap. In front of 1,500 fans, Armstrong took the pitcher’s mound to ceremonially (and with much camp) strike out the first batter. The crowd went wild.

3. The halftime show to end all shows

A halftime show featuring Mary Poppins and a man wearing a jetpack was just one of the events conceived by Tommy Walker. (THNOC, gift of Roy Trahan, 1990.16.1.1229)

Walt Disney hired Tommy Walker in 1955 to make magic at his new theme park—the iconic fireworks show above the castle came from him—and after 12 years there the showman took his talents to New Orleans for the inaugural Saints season. In addition to producing three Super Bowl halftime shows, Walker kept Saints fans entertained during mid-game breaks, recruiting local musical icons to perform, including partial team owner Al Hirt and the Olympia and Eureka brass bands. These elaborate halftime shows ended in 1970 after a participant lost several fingers in a cannon incident during a reenactment of the Battle of New Orleans.

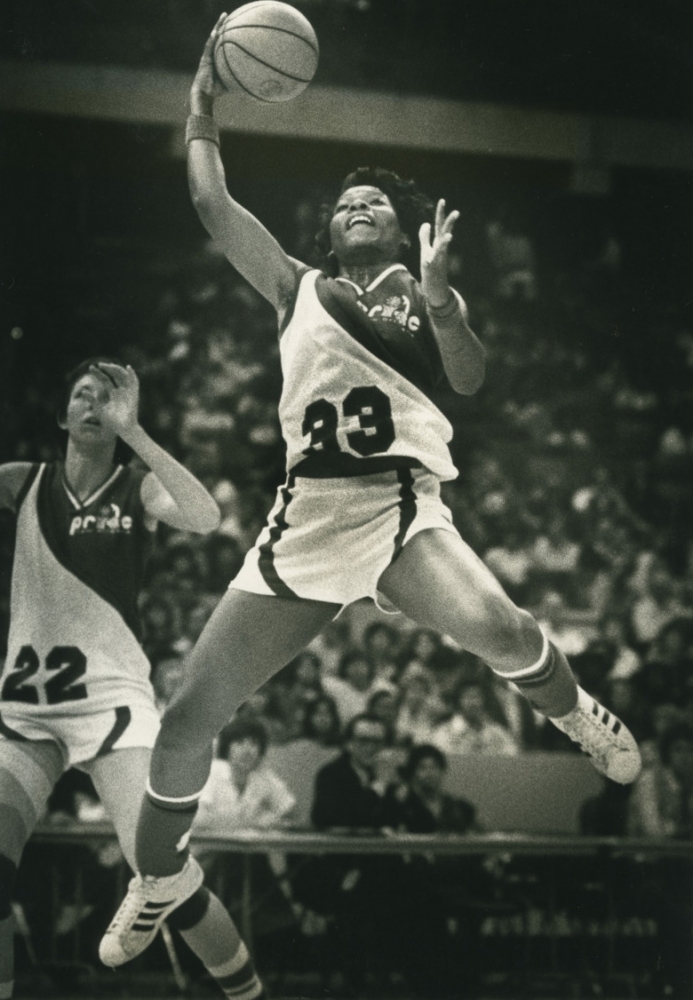

4. A team in the cradle of women’s basketball

A press photograph features Bertha Hardy, a New Orleans Pride basketball player, scoring two points in the first half of a game from the 1980 season. (THNOC, gift of John H. Lawrence, 2018.0557.18)

More than eight decades after New Orleans’s own Clara Baer published the first rulebook for women’s basketball, the city, fittingly, fielded a team in the first pro league for women. The New Orleans Pride joined the trailblazing Women’s Professional Basketball League (WBL) in its second season.

A crowd of 8,452 fans poured into the Superdome to witness the Pride’s debut against the New York Stars on November 15, 1979. The home team lost 120–114, but the attendance ranked among the highest the WBL had seen, an auspicious sign for the Pride and the league. The WBL’s founders anticipated that owners might lose money the first few years, but they were banking on the exposure the sport would get at the 1980 Olympics, which would feature women’s hoops for the second time. That opportunity vanished when the US and 65 other countries boycotted the Moscow-hosted games in protest of the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan. The league couldn’t get the traction it needed and folded in 1981.

During its brief run, the WBL offered what was perceived as a more team-oriented style of play, which won over some fans who lamented the dominance of individual players—especially big men—in the NBA. Times-Picayune sportswriter Peter Finney admiringly listed the contrasts seen at a Pride game: “No slam dunks. More pattern play than one-on-one. More screens. More passing.” Fans still enjoy the fluidity of team-oriented play in today’s WNBA—and the dunking, too.

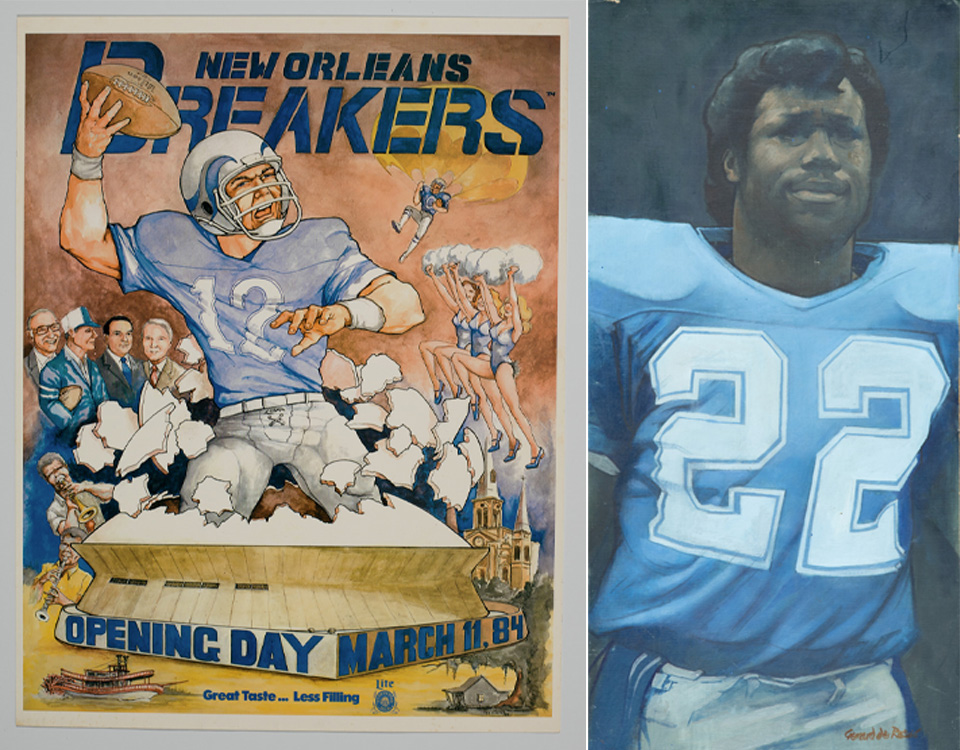

5. The ballad of Marcus Dupree

The New Orleans Breakers were the city’s USFL franchise. Marcus Dupree dropped out of college to play with the team, after a tumultuous college career. (left: THNOC, gift of David and Mary Dixon family, 2009.0157.77;right: Courtesy of Joseph C. Canizaro)

The brainchild of New Orleans sports promoter Dave Dixon, the United States Football League debuted in March 1983, and in three seasons introduced major innovations such as the two-point conversion and instant replay that were later adopted by the NFL. The USFL also revolutionized pro football’s relationship with the college game, which helped Marcus Dupree, one of the era’s biggest young stars, land with the New Orleans Breakers franchise.

The USFL broke a long-standing pro football rule against allowing college underclassmen to turn pro when it allowed Georgia star Herschel Walker to sign with the New Jersey Generals after his junior year, in 1983. A year later a similar exception was made for Dupree. Dupree’s sensational high school performances in the small town of Philadelphia, Mississippi, attracted one of the most intense recruiting frenzies ever, but his collegiate experience proved tumultuous. He switched schools during his sophomore year resulting in the NCAA declaring him ineligible to play through his junior year, so he dropped out and signed a contract with the New Orleans Breakers worth $6 million.

He scored nine touchdowns in his first season in New Orleans but suffered a catastrophic knee injury in 1985 that effectively ended his career. Not long after that, he was swindled out of most of his money by a corrupt agent. The 2010 ESPN documentary The Best That Never Was traced Dupree’s star-crossed career. Today he works for a nonprofit agency in Mississippi and is involved in an array of business ventures.

These stories are excerpted from Crescent City Sport: Stories of Courage and Change, on view at 520 Royal Street, November 22, 2019–March 8, 2020.