For centuries, Freemasons and the Independent Order of Odd Fellows have been central to civic, social, and cultural life in the United States. These fraternal orders’ roots go back to guilds formed by stonemasons and craftsmen in Europe near the end of the Middle Ages. In addition to overseeing standards for education and pay, guilds provided shelter and fellowship to members who were constantly on the move for work. Members of European fraternal orders traveled to colonies in the Americas, where their organizations thrived. By 1900, some 20 to 40 percent of men in the US were members of at least one fraternal order.

New Orleans saw the establishment of its first fraternal orders in the 18th century, and by the mid-19th century, Masonic and Odd Fellows lodges—a term that refers to both the organizations and the buildings associated with them—were an integral part of life in the city for both Black and white men. (Women were excluded from joining the all-male lodges, but there were female auxiliary groups.) Beyond the bonds of fellowship, fraternal lodges provided practical benefits to their members—help with medical bills and relief payments to compensate them during illness; funerals and support to beneficiaries after death. In this way, fraternal orders’ economic impact extended beyond their ranks, to undertakers, physicians, and druggists, as well as to brass bands that performed during funerals and annual parades.

Freemasons and Odd Fellows have also had a lasting impact on the local architectural landscape. Their lodges—some of which remain active in the city today—can be seen in neighborhoods across New Orleans. Here’s a sampling of these historic buildings.

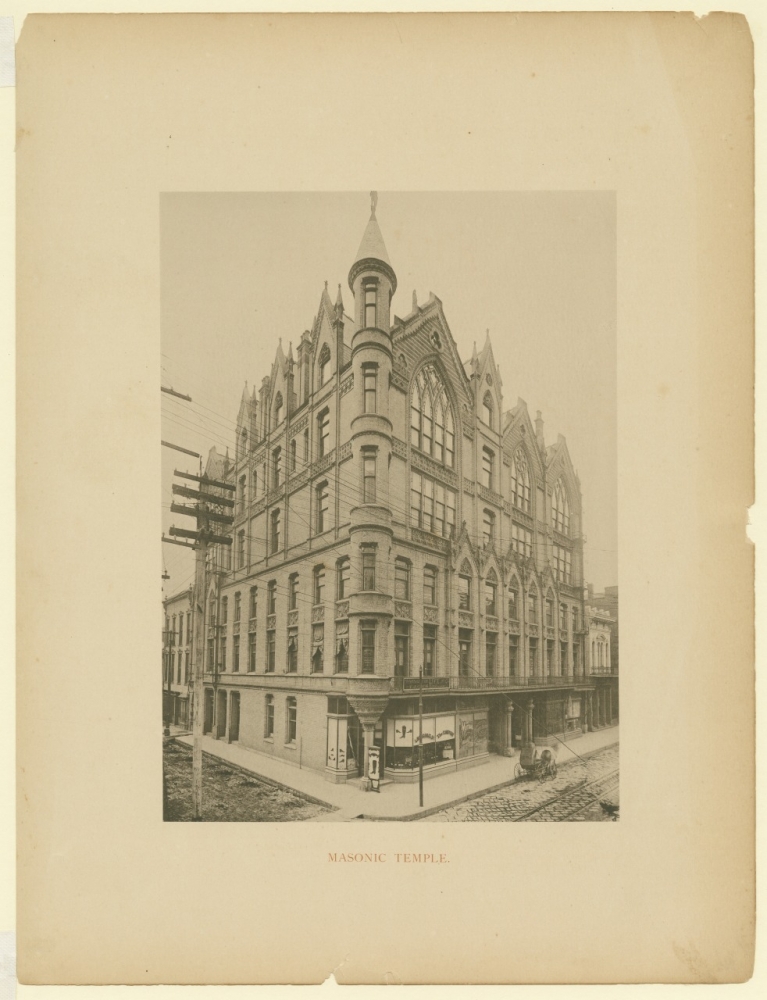

333 St. Charles Avenue

(THNOC, 1974.25.3.681)

This Gothic-style building, designed by architect James Freret, was the home of the Grand Lodge of the State of Louisiana from 1892 to 1925. Prior to that time, the Masonic lodge, which was chartered in 1853, had been operating from the Commercial Exchange building on this site. Freret’s castle-like structure had a peaked roof, ornate dormers, and intricate friezes, but it proved to be ill-suited for maintenance and adaptability. The building was razed after only three decades.

(The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.377 )

This neo-Gothic building designed by Stone Brothers and built by James Stewart and Co. replaced the Freret structure in 1926. The Grand Lodge sold the property to hotel developers in 1982 and moved their headquarters to Alexandria, Louisiana. The building is currently a Hilton hotel.

1433 North Rampart Street

(THNOC, gift of Arts Council of New Orleans, 1996.93.50)

Constructed around 1847, this building near North Rampart and Esplanade continues to serve as the home of the Etoile Polaire No. 1 Lodge, which was established in 1794. The lodge was a prominent association for white Creoles, and members conducted their Masonic rites in French until the 1950s. The cast-iron gate was added in the 1880s. The first floor is used for public events, including dances and live music, while the second floor is reserved for private lodge functions.

4415 Bienville Street

(THNOC, gift of Kris Pottharst, 2011.0299.4.56)

Germania Lodge No. 46 on Bienville Street opened in 1930, two years after the group’s older lodge on St. Louis Street was sold. In the late 1950s and early ’60s, the Germania building hosted wedding receptions and Saturday night dances for teenagers that featured legendary New Orleans R&B performers such as Ernie K-Doe, Irma Thomas, and Professor Longhair. Today, several Masonic organizations hold their meetings here.

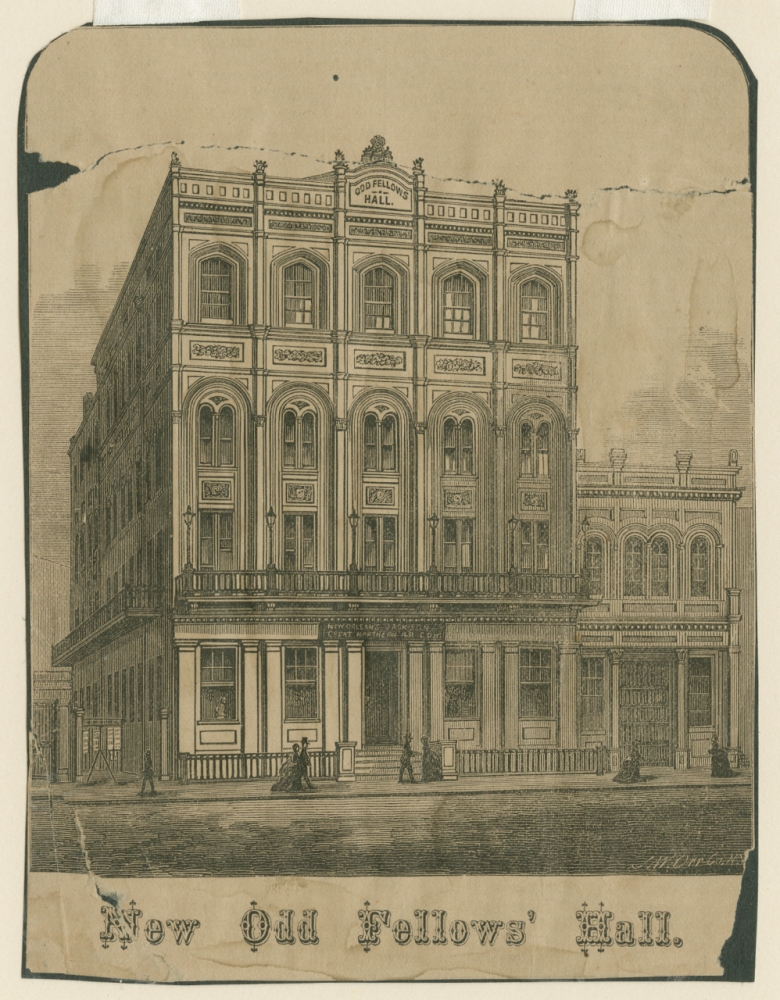

600 block of Camp Street

(THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1954.9.6)

The original Odd Fellows Hall in New Orleans, constructed in 1852, was damaged during the Civil War. After the war, surviving association members borrowed $50,000 to make repairs, but two days after they secured the funds, a fire destroyed most of the building. The Odd Fellows acquired a nearby property on Camp Street between Poydras Street and Lafayette Square and built the new hall there.

500 block of Camp Street

(THNOC, 1974.25.3.274)

Constructed over 1867–68, the new Odd Fellows Hall was the site of much controversy during Reconstruction. In 1872, the results of the race for governor—between Democratic-Conservative candidate John McEnery and Republican candidate William Pitt Kellogg—were contested. When Kellogg was declared the winner, McEnery and his supporters used the Odd Fellows Hall to operate a shadow government in competition with Kellogg’s administration. In March 1873, McEnery’s supporters were forced from the hall by the Republican-controlled Metropolitan Police, and in September 1874, McEnery finally conceded the election. The Odd Fellows continued to occupy this hall—hosting musical performances, dances, Carnival balls, and public lectures—until 1914, when the building was demolished.

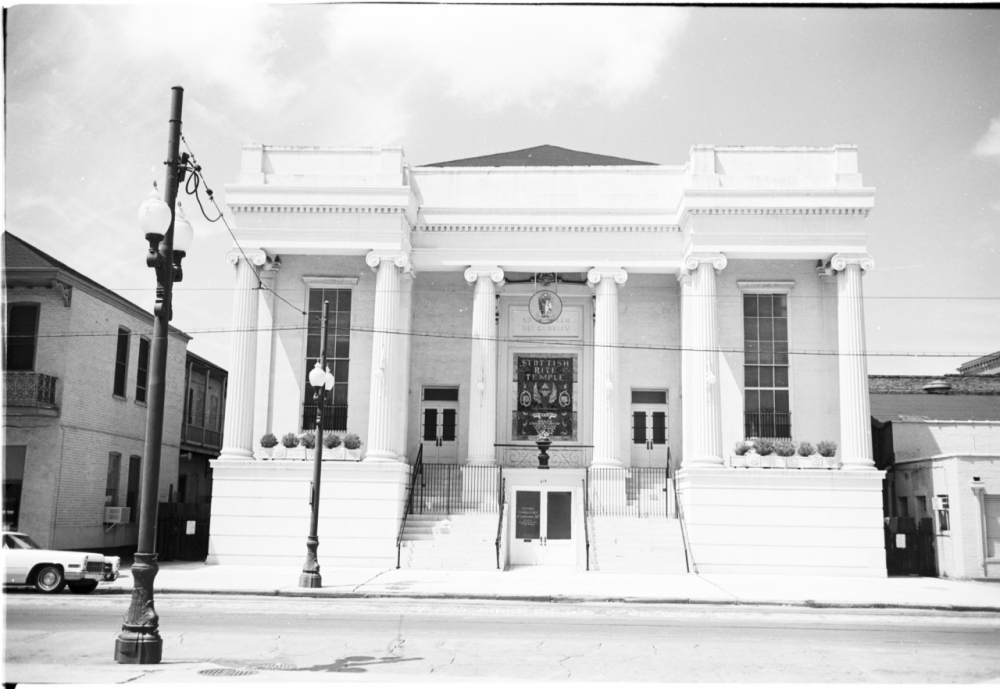

619 Carondelet Street

(THNOC, 1976.30.144)

This building was constructed as a Methodist church in 1853. In 1905 the Grand Consistory of Louisiana, which oversees the highest degrees of the Scottish Rite Masons, purchased the property to serve as the Scottish Rite Temple. The temple’s dedication in November 1906 included an unveiling of the central stained-glass window, prominently featuring the Latin phrase “Spes Mea in Deo Est” (In God Is My Hope), the motto of the rite’s 32nd degree. The Grand Consistory maintained ownership of the property until 2015.

222 North Roman Street

(THNOC, 1994.138.34)

Organized by free men of color in 1844, St. James was the first African Methodist Episcopal church established in the Deep South. The current neo-Gothic edifice was built in 1848 and renovated in 1903. Richmond Lodge No. 1, which was affiliated with the historically Black branch of Freemasonry known as Prince Hall, was organized at this site in 1849 by Rev. Thomas W. Stringer, a pioneer of African Methodism and Freemasonry in the South.

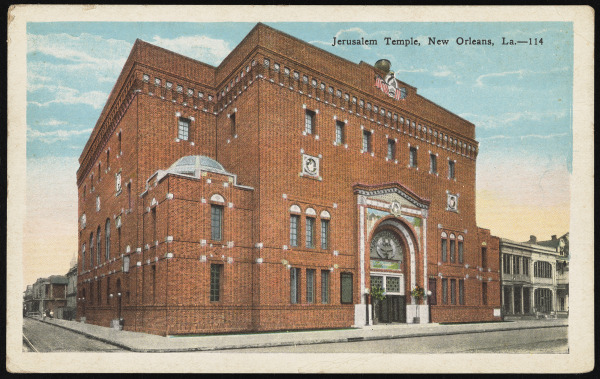

1137 St. Charles Avenue

(THNOC, 1981.350.3)

This hall was designed for the Jerusalem Temple Shriners by local architect Emile Weil in 1918. Its Moorish Revival style was frequently used for Shriners’ temples but is not common in New Orleans architecture. In its heyday, the hall hosted Mardi Gras balls for krewes such as Apollo and Les Pierrettes; high school dances; and recitals. In recent years, following the Jerusalem Temple moving its headquarters to Destrehan, the building has served as a Christian church.

To learn more about Freemasons and Odd Fellows, visit A Mystic Brotherhood: Fraternal Orders of New Orleans, on display from December 8, 2023 to May 10, 2024.