The “Coming to New Orleans” series, presented in conjunction with American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith, tells stories of New Orleans immigration history through items in our holdings. Read the first part of the series, a timeline that looks at New Orleans immigration in the context of immigration to the US, here.

Between World War I and the passage of the Civil Rights Act, the United States became more connected to Latin America than in any other period in its history, with New Orleans serving as a major gateway. Though New Orleans was part of the Spanish Empire from 1763 to 1803, very few Spanish officials permanently settled in Louisiana. Therefore, most Hispanic immigrants to Louisiana have come from outside the Iberian Peninsula, largely from former Spanish colonies in the Americas. In the late 18th century, Hispanic immigrants began arriving in the New Orleans area from the Canary Islands, a Spanish colony off the northwestern coast of Africa. In the 19th century a small number of economically prosperous Mexican immigrants arrived, along with a contingent of Cubans who were working with Louisianians to achieve independence from Spain. But the largest group of immigrants of Hispanic origin came in the mid-20th century. Hailing primarily from Central America and Cuba, they brought new energy to the economic, political, and cultural development of the Crescent City.

The City of New Orleans reached its peak population of over 600,000 residents in the 1960s thanks in part to these new immigrants and the expansion of and investment in New Orleans’s suburbs and new residential neighborhoods. Immigrants to New Orleans faced challenges at the federal level with the quota system, the commonly used name for a law passed by Congress in 1924 that limited legal immigration based on nation of origin. The rise of anticommunist hysteria following World War II led to increased scrutiny of immigrants. These laws resulted in the lowest immigration United States immigration rates of the twentieth century during the 1950s and '60s. However, the growth and development of the city remained an attractive pull for those in the Americas seeking better opportunities and cultural familiarity in the United States.

Honduran Immigrants

(THNOC, gift of Mrs. James P. Ewin Jr., 1984.106.32i,ii)

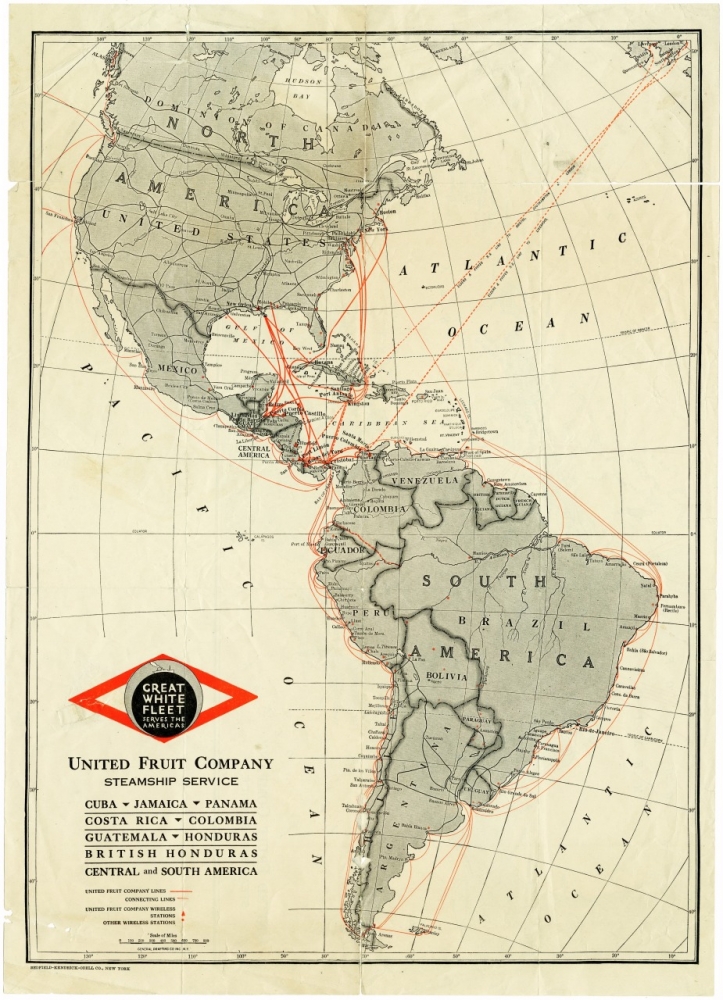

The rise of the banana import industry at the dawn of the 20th century facilitated a close connection between Honduras and New Orleans. Migrants first began arriving from Honduras aboard refrigerated steamships carrying bananas operated by the United Fruit Company as early as the 1910s. Some of the reasons for this early migration included continued employment with fruit companies, educational opportunities at New Orleans Catholic schools for employees’ children, and Black West Indians and Afro-Latinos fleeing racial discrimination in Honduras. This circa-1930 map shows the many ports in the Americas serviced by the United Fruit Company Passenger Steamship Service. Some of the darkest red lines converge on New Orleans, signifying that it was the preferred port of entry for Central Americans arriving in the US.

(THNOC, 2023.0164)

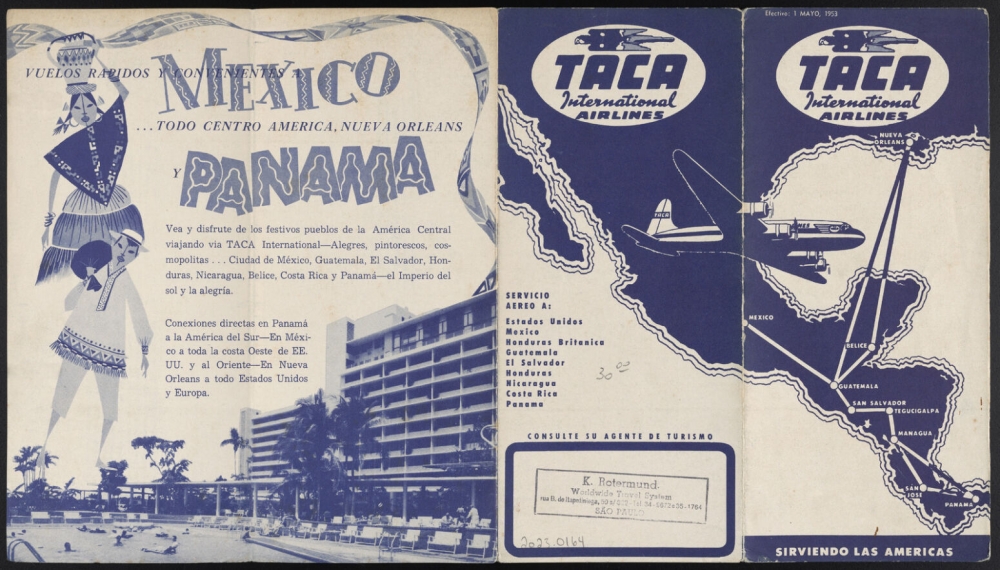

As airplanes began to replace steamships for overseas travel, TACA Airlines (Transportes Aéreos de Centro América, or Airline Transports of Central America) became the dominant mode of transportation for bringing Central Americans to the city. This 1953 pamphlet distributed by the airline includes timetables for flights between New Orleans, Central America, and South America. Colloquially, the airline’s acronym TACA came to stand for “Take A Chance Airlines,” as Honduran migrants post-1950 were fleeing low employment, political repression and instability, as well as hurricanes. New Orleans attracted Hondurans because of its accessibility, environmental similarities, Catholic culture, and the prospect of continued employment in the fruit trade, where bilingual speakers were in high demand. These Hondurans were a racially and ethnically diverse group, including white European descendants, mestizos, Afro-Indigenous groups like the Garifuna people, and Black West Indians. Because of this racial diversity, some Hondurans faced challenges entering the black-white binary of Jim Crow New Orleans. However, some scholars argue that they faced less oppression than Hispanics in the Southwest due to the relative social mobility enjoyed by Spanish speakers.

As immigration from Honduras increased during the 1950s and ’60s, a community of Honduran expatriates, or Catrachos, as they call themselves, began to form in the Lower Garden District, which they called El Barrio Lempira, named after a Honduran national hero killed by the Spanish in the 16th century. Hondurans opened businesses catering to their community, including restaurants, supermarkets, and nightclubs, as well as a Spanish-language radio station, KGLA. By 1962, New Orleans had the largest Honduran population in the United States, a distinction later taken by New York City. Between 1970 and 1980 the Honduran community doubled in size but remained below 10,000. In the 1970s Hondurans began out-migrating to the suburbs, primarily Kenner, Gretna, and Terrytown, following a trend among white residents of the Crescent City. In relative size, Hondurans remained the largest Hispanic group in the New Orleans area until the arrival of Mexican immigrants following Hurricane Katrina.

(Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.2454)

Community life for these Catholic immigrants centered around the St. Theresa of Avila Church at 1401 Erato Street, which offered Spanish-language masses. Here, Hondurans could celebrate the feast day of Our Lady of Supaya, the patron saint of Honduras. This photograph, by the firm of Charles L. Franck, shows the exterior facade of St. Avila’s church sometime around 1953, when the Honduran community was growing and Fidel Castro was coming to power in Cuba, inspiring many anticommunist Cubans to flee to the United States. Cubans and Hondurans both worshipped at this church in the Lower Garden District, providing a space for the growing New Orleans Hispanic community to come together.

Cuban Immigrants

Cubans had been emigrating to New Orleans since the mid-19th century and continued as the sugar and fruit trades increased at the turn of the 20th century, but it wasn’t until the rise of Fidel Castro in 1959 that Cubans began arriving to the city in large numbers. Thousands of Cubans opposed to the revolutionary government left for the United States, especially to Miami. The Catholic Church sought other cities to alleviate the burden. Hundreds of Cubans came to New Orleans, attracted to the Catholic culture, business connections, and similar climate. In 1962, the Catholic Cuban Center began providing health care and resettlement services to these new immigrants, whose asylum status prevented them from accessing public assistance programs. Language barriers and issues with US employers not honoring foreign certifications also forced many Cuban professionals to take low-paying jobs.

(THNOC, 1988.161.35)

In the 1950s and ’60s, Mayors Chep Morrison and Victor Schiro understood the importance of Latin American trade connections and made efforts to strengthen these ties during their administrations. Morrison worked to preserve and develop New Orleans’s commercial relationship with Cuba with goodwill trips and press junkets throughout his administration, which lasted from 1946 to 1961. This photograph documents Morrison’s trip to Cienfuegos, Cuba, in July 1954. He is seen speaking to Cuban politicians and business leaders at a banquet. In May 1959, Schiro, then a city councilman, accompanied Morrison and a delegation of 152 representatives to Havana to showcase Mardi Gras at Cuban Carnival. Schiro, who had spent part of his childhood in Honduras, spoke Spanish fluently. This skill allowed him to be an active member of the Latin American political and business spheres.

President Kennedy enacted a trade embargo between Cuba and the United States in 1962, which put an end to the commercial relationship Morrison and Schiro had worked so hard to maintain. During his administration in the late 1970s, Mayor “Dutch” Morial appointed the first Cuban American to municipal office, Tony Naranjo, in the newly created Office of Hispanic Affairs. In his second term, Morial created the Latin American Task Force to address the needs of the community. As the New Orleans economy stagnated in the 1980s and ’90s, immigration from Cuba slowed down and the Hispanic population saw little to no growth until after Hurricane Katrina. Though many of the city’s Cuban immigrants eventually moved to Miami, Cubans remain a visible part of New Orleans’s Hispanic community.

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook or Instagram.