The exhibition Making Mardi Gras, on view now, celebrates the craftspeople and artists who help create this magical time of year. Photographers, too, play an important part in documenting the otherwise ephemeral beauty of a float, a dance routine, or a Black Masking Indian’s suit. Here are a few photographs from the exhibition that explore the many traditions of Mardi Gras and the creative vibrancy and artful techniques that make it “The Greatest Free Show on Earth.”

Image taken by George Ernst Durr in 1915 (THNOC, gift of Kris Pottharst, 2011.0299.1.69)

This photograph, compiled in a scrapbook, is one of the earliest images of Black Masking Indians (a.k.a. Mardi Gras Indians) at THNOC and was taken at the intersection of Canal Street and Claiborne Avenue on Mardi Gras Day 1915. The image is out of focus, but visible suit details—including the headdresses, shirts, pants, and breechcloths—offer a contrast to the colorful suits worn by Black Masking Indians today.

Image of a lieutenant from the Krewe of Rex taken circa 1921 (THNOC, 1980.45)

This straightforward portrait of Ernest Doty Ivy, a Rex lieutenant, was taken circa 1921. It shows him wearing a Mardi Gras costume that includes a Rex ducal decoration, black riding boots, long black gloves, cape, wig, hat, and mask. This colorful image was made using the autochrome process, the first color photographic process made with dyed potato starches. Due to its light sensitivity, a reproduction has been made for Making Mardi Gras.

Image taken by Charles L. Franck Photographers in 1934 (From the Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.3868)

These two women celebrated Mardi Gras Day 1934 as many still do now: by coordinating matching costumes and heading down to Canal Street, where thousands of people gather to watch parades. Made with a shiny black fabric, their ensembles feature pants, peplum tops, ruffled collars, and—of course—masks to disguise their identities.

Image taken by Ryan Hodgson-Rigsbee in 2016 (THNOC, 2021.0203.12)

French artist George Soulié, who specialized in papier-mâché, brought the technique to New Orleans in the late 19th century. Today papier-mâché is still used by local float-building company Royal Artists. The company was founded in 1975 by Herbert Jahncke Jr. and is now directed by Richard Valadie. In this image, an artist is seen making a large papier-mâché piece to be affixed to a float base.

Image taken by Ryan Hodgson-Rigsbee in 2013 (THNOC, 2021.0203.6)

The New Orleans Baby Doll Ladies was founded in 2005 by Millisia White with a stated mission to “embody, encourage, and expose Louisiana vernacular folk artistry throughout communities.” The ladies continue the tradition of Baby Doll groups in New Orleans that date back to Black Storyville in the early 20th century. On Mardi Gras Day you can catch them dance-parading after Pete Fountain’s Half-Fast Walking Club rolls and before the Zulu parade begins.

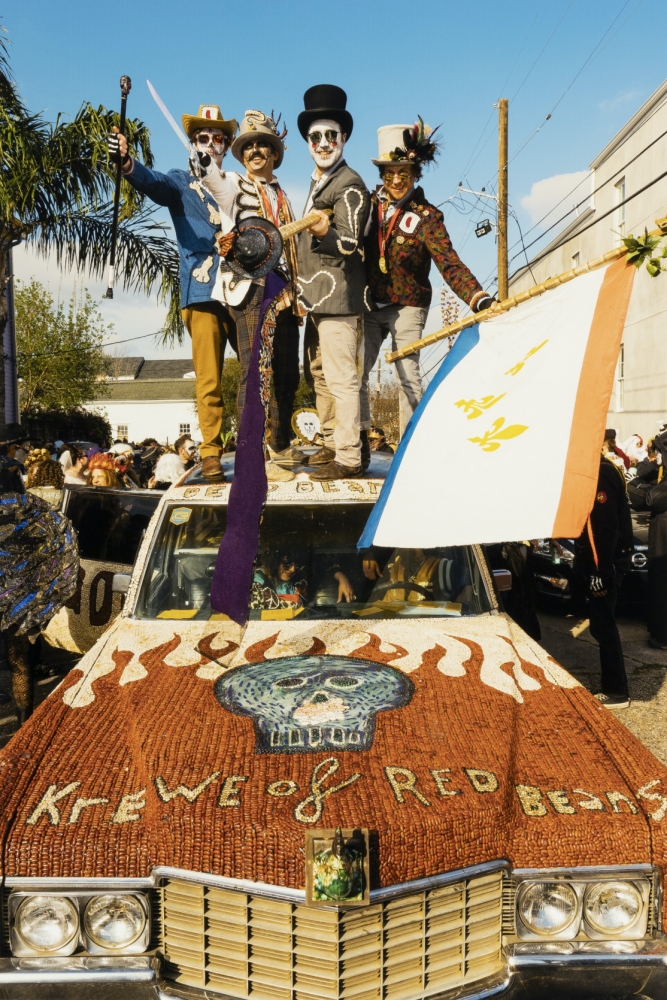

Image taken by Ryan Hodgson-Rigsbee (THNOC, 2021.0203.13)

The Krewe of Red Beans was founded in 2009 by a small group of friends who were inspired by the craftsmanship of Black Masking Indian suits. Each Lundi Gras, the Monday before Fat Tuesday, the krewe walks around sporting their creative bean designs that include bean puns. No accessory—even a car, as this photograph shows—is off limits when it comes to bean embellishment. During the pandemic, the Krewe of Red Beans started a mutual aid organization in support of local musicians, artists, service industry, and frontline workers. They have continued to their mutual aid efforts and are currently raising funds for a community center called Beanlandia.

Image taken by Ryan Hodgson-Rigsbee in 2019 (THNOC, 2021.0203.10)

Founded in 1969, the Société de Saint Anne began as a small group of friends who met at a house in the Bywater and made their way through the French Quarter to the banks of the Mississippi River. The krewe continues this tradition, holding a memorial service on the riverbank each year, allowing participants to memorialize loved ones lost during the previous year. Some scatter ashes. The memorial gathering became more much impactful during the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, as krewe members and the community at large suffered the loss of many loved ones.

Image taken by Ryan Hodgson-Rigsbee in 2019 (THNOC, 2021.0203.1)

Emphasizing small but impeccably detailed shoebox floats and known as the Crescent City’s only “micro-krewe,” ‘tit Rex has over a 15-year waiting list to join. The parade allows for 30 floats, each pulled by its creator. In this photograph, some creative spectators joined the fun with their own miniature crowd scene, complete with Mardi Gras ladders, tarps, coolers, and signs to greet the passing floats.

Image taken by Akasha Rabut in 2015 (THNOC, 2021.0184.2)

This image, titled Bria’s Birthday, shows the Edna Karr High School dance team on the NOMTOC parade route on the West Bank. Edna Karr’s dance team and marching band are fixtures of the Carnival parade season and even appeared in Beyoncé’s 2016 music video for “Formation.” Many female walking krewes have used African American high school dance teams as inspiration for their dances and costumes.

Image taken by Ryan Hodgson-Rigsbee in 2021 (THNOC, 2021.0203.11)

Cherice Harrison-Nelson’s family has masked Indian for five generations, and, in addition to founding the Mardi Gras Indian Hall of Fame, she has been a vocal advocate for the artistic rights of Indians and their often-photographed handiwork. She designs and creates suits that visually express tradition, community, identity, and her West African heritage. In this photograph, she wears the suit she created in 2021, which was inspired by the Yoruba water deity Olokun.