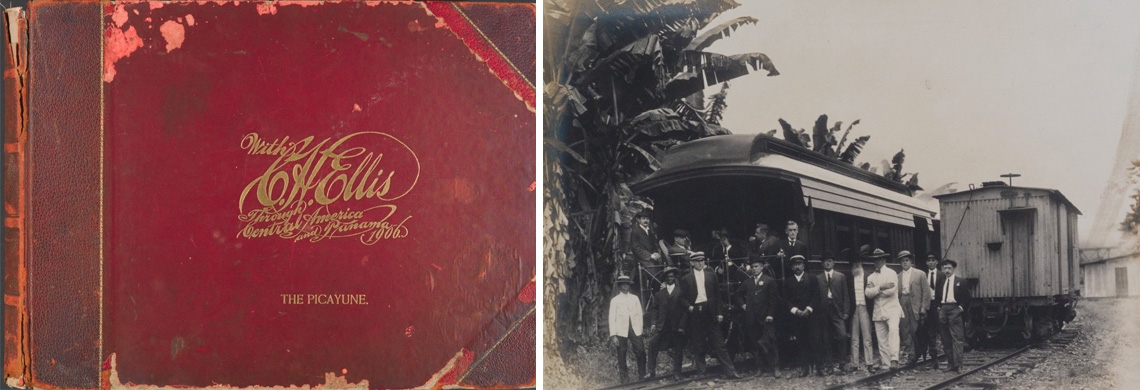

As cities and states weigh the economic consequences of closures related to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, I have been reminded of the last object I worked on before the stay-at-home order went into effect on March 13, 2020. A large photograph album bound in red leather, it documents a 1906 “quarantine tour” of Central America sponsored by the United Fruit Company during the final outbreak of yellow fever in New Orleans.

The photo album is a fascinating example of the tremendous influence of the banana-import business in early 20th-century New Orleans (view the entire album here). The so-called quarantine tour was essentially a public relations campaign to combat a strict ship quarantine during the yellow fever outbreak of 1905. When I cataloged the item back in February, I had little idea how relevant it would be to our current reality, but it stands as a 115-year-old example of a now familiar conflict, between powerful commercial interests and public health officials. To understand the historical context for this tour, we need to take a brief look at the history of bananas and yellow fever in New Orleans.

Dock workers handle bananas on a conveyer belt being unloaded from a United Fruit Company steamship at the Thalia Street wharf in the 1930s. This wharf, used exclusively by the United Fruit, was rumored to be the epicenter of the 1905 yellow fever outbreak in New Orleans. (The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.3577)

New Orleans was one of the largest importers of bananas in the United States at the turn of the 20th century. First introduced at the 1876 World’s Fair, in Philadelphia, bananas quickly became a staple in the national diet, thanks in part to aggressive marketing. As the ports of New Orleans, Boston, Philadelphia, New York, and Mobile began to import bananas, distribution services developed to get the produce to market quickly. Speed was especially important in the era before refrigeration, as cargo would spoil in a matter of days. In New Orleans, bananas were unloaded at the Thalia Street wharf; a portion was sold at local produce markets, and the rest were loaded onto railroad cars and shipped around the country. The importation of the fruit cemented the city’s relationship with Latin America, where United Fruit established a stronghold in the region’s politics, economy, and real estate.

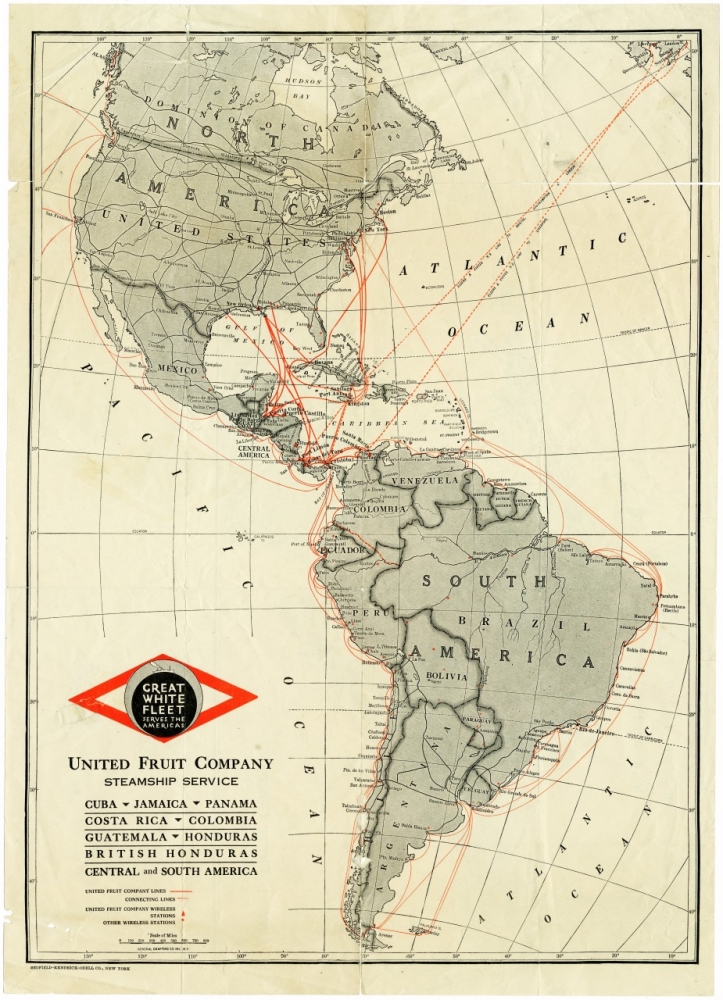

A circa 1930 map shows the United Fruit Company’s network of steamship lines. The company owned banana plantations in Central America, South America, Jamaica, and Cuba and exported the fruit to ports in the United States and the United Kingdom. (THNOC, gift of Mrs. James P. Ewin Jr., 1984.106.32 i)

The Boston-based United Fruit Company, now Chiquita Brands International, was formed in 1899 by railroad magnate Minor Keith and businessman Andrew Preston. Keith, the company’s vice president, laid the foundations for the banana trade in the 1870s, when he began the construction of a railroad in Costa Rica connecting the capital, San José, to the port city of Limón. An estimated 5,000 Central American workers died during the course of the project, many of them casualties of yellow fever, which spread quickly amid the labor camps’ poor sanitation and health conditions. (At that point, mosquitos had not yet been discovered as the vector of the disease’s transmission.) As a result, Keith used prison labor from New Orleans to complete the project.

To feed his overworked labor force as cheaply as possible, Keith planted banana trees in the vast amount of land that he owned around the railroad. Although the railroad was originally intended to transport coffee for the Costa Rican government, by the completion of the project in 1890, Keith was moving massive amounts of bananas to the port of Limón to sell in the United States. Keith then approached Preston at the Boston Fruit Company, who already had a distribution network of refrigerated steamers, and the United Fruit Company was born.

From 1899 to 1905, United Fruit expanded into Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama through government contracts that traded real estate for the construction of railroads and other public works. Its rapid acquisition of land and political control earned United Fruit the moniker El Pulpo, or “the octopus,” for the extent to which its “tentacles” reached into every corner of politics in the region.

Central American countries that produced bananas for United Fruit and other import companies became known as “banana republics,” as their entire governments were focused around the trade of a single crop (the Gros Michel banana), to the detriment of their own people and development. The local people working these plantations were paid poverty wages, and efforts to organize were violently quelled: in 1928 United Fruit extinguished a strike in Colombia by opening fire on an untold number of workers and their families in what became known as the Banana Massacre. (Author Gabriel García Márquez drew from the tragedy in his novel One Hundred Years of Solitude.) Diseases such as yellow fever were a constant menace to workers, but the company did not move to improve sanitation conditions until its business was threatened by bad press coming out of New Orleans.

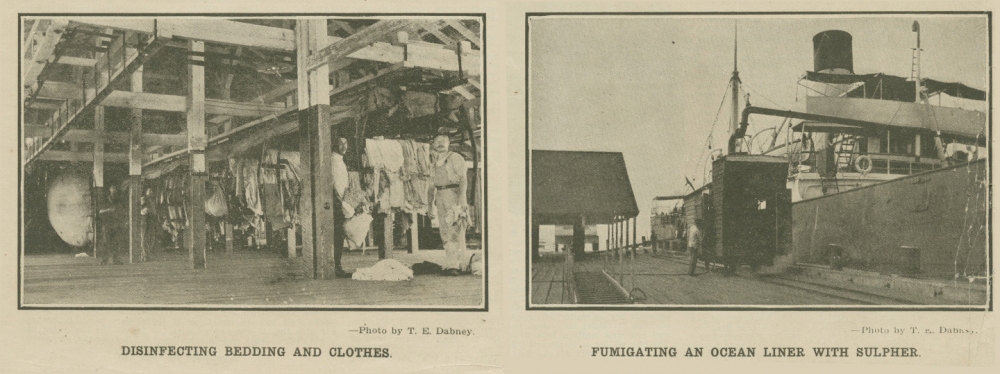

Two newspaper photographs show a completed quarantine station at Southwest Pass circa 1910. On the left, two men disinfect bedding and clothes to combat the spread of yellow fever while, on the right, an ocean liner is fumigated with sulphur. These practices proved detrimental to edible cargo and were a major point of contention between the Louisiana State Board of Health and fruit import companies like United Fruit. (THNOC, 1974.25.11.181 i-xiii)

Two newspaper photographs show a completed quarantine station at Southwest Pass circa 1910. On the left, two men disinfect bedding and clothes to combat the spread of yellow fever while, on the right, an ocean liner is fumigated with sulphur. These practices proved detrimental to edible cargo and were a major point of contention between the Louisiana State Board of Health and fruit import companies like United Fruit. (THNOC, 1974.25.11.181 i-xiii)

Oceangoing steamships, such as those operated by United Fruit, were routinely inspected for yellow fever, which plagued New Orleans off and on for much of the 19th century. As early as the 1810s, quarantining of ships by the newly formed Louisiana State Board of Health was a common practice. After the city’s worst outbreak of yellow fever, in 1853, quarantine stations were established at Fort Jackson on the Mississippi River south of New Orleans and at the Rigolets at the entrance to Lake Borgne. At these quarantine stations, ship passengers would be inspected by a doctor while the ships were made to wait an average of 10 days before being allowed to dock at the port.

After the yellow fever outbreak of 1878, the quarantine stations began the practice of disinfecting cargo holds of vessels by fumigating them with sulphuric acid gas. Fruit dealers were especially outraged by this practice, signing a petition in February of that year in protest against the Board of Health when a cargo of bananas, already on a tight schedule, was discolored and ruined by the fumigation. Once the 1878 outbreak subsided, New Orleans experienced relatively few deaths from yellow fever thanks to scientific discoveries and sanitation improvements. That is, until it all came crashing down in the summer of 1905, this time on the head of one of the city’s biggest industries.

When cases of yellow fever were reported in Belize and Panama in May of that year, New Orleans suspended all imports from Central America, causing United Fruit shipments to pivot to port cities in Mississippi. By July, the epidemic had reached New Orleans when, reportedly, a worker at the Thalia Street wharf contracted the disease while unloading a shipment of bananas from a United Fruit steamship. Consumers became convinced that the company’s Central American ports were infested with the disease, and the public largely blamed United Fruit for the outbreak.

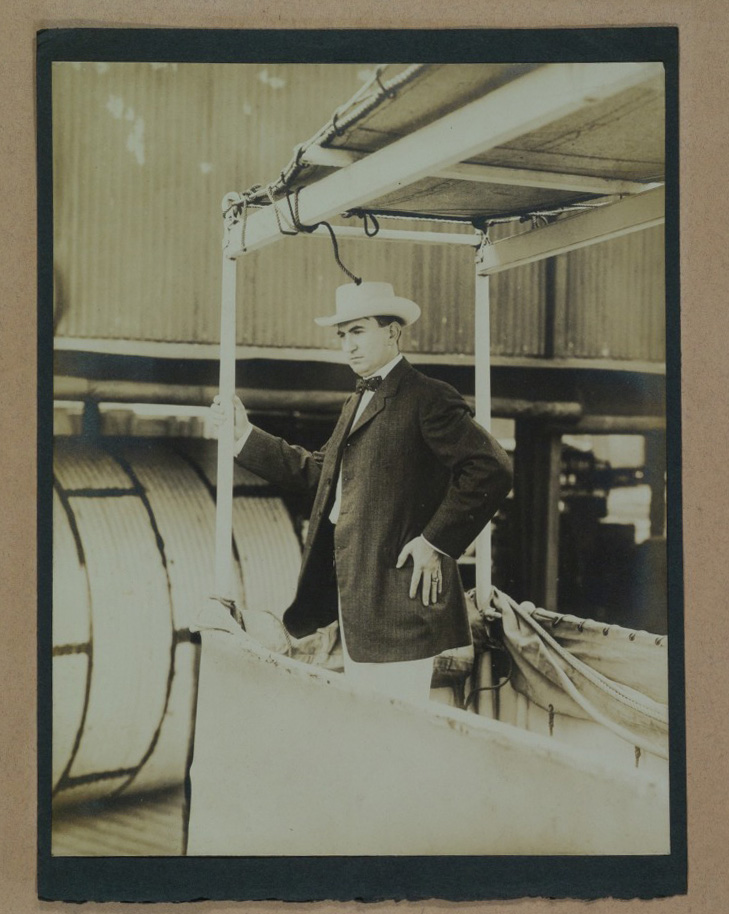

In December, Crawford H. Ellis, the manager of United Fruit’s New Orleans operations, published a defense in the Daily Picayune pleading the company’s innocence and threatening to prosecute “anyone who accuses them of quarantine violations or collusion with health officials” for criminal libel. In the article, Ellis outlines steps taken by the company to keep its ports, cargo, and workers protected from disease and free of mosquitos (by this time known to spread yellow fever), and he offers several other theories for where the epidemic originated—including one implicating rival fruit-import companies from Havana.

Crawford H. Ellis, manager of the New Orleans branch of United Fruit Company, is shown aboard the steamship Anselm during the 1906 quarantine tour of Central America. Ellis professed that he would sue any reporter who blamed the 1905 yellow fever outbreak on United Fruit, and invited press and photographers on his quarantine tour to disprove their allegations. (Photograph by John N. Teunisson; THNOC, 1996.14.1)

Among the city’s business community, there was a real fear that New Orleans wasn’t going to be able to hold on to the fruit trade, and United Fruit saw an opportunity to convince health officials that it was committed to halting the spread of disease by showing them firsthand the improvements the company had made to its Central American ports. United Fruit called it a “quarantine tour.”

Led by Ellis, the tour embarked on January 20, 1906, aboard the company steamship Anselm. United Fruit invited a host of officials—representatives from neighboring state boards of health; Marine Hospital Service executives; reporters from the Times-Democrat, the Picayune, and the Mobile Register—to inspect and report on the health conditions of its operations in Central America.

To document the voyage, local freelance photographer John N. Teunisson accompanied the tour. Upon his return, Teunisson worked with a typesetter and publisher to compile the 83-page photo album featuring 69 photographs of company-owned buildings, hospitals, wharves and ports, railroads, views of cities and towns, and images of the traveling party, along with 14 accompanying pages of interpretive text about the sanitary conditions and risk of infection at each port. The production of the photo album was sponsored by the United Fruit Company, so the information contained in it was likely supplied by the company as well. The interpretive text concerning port conditions was probably drawn from the reports made by health officials accompanying the tour.

The traveling party, including Crawford H. Ellis at the bottom left, is pictured standing in front of a train on a railroad built by Minor Keith in Port Limón, Costa Rica. During its construction in the 1880s, Keith planted banana trees, like the ones pictured here, along the route as cheap food for his labor force. By the time the railroad was completed in 1890, the train was used solely for transporting bananas. (THNOC, 1996.14.13)

The traveling party, including Crawford H. Ellis at the bottom left, is pictured standing in front of a train on a railroad built by Minor Keith in Port Limón, Costa Rica. During its construction in the 1880s, Keith planted banana trees, like the ones pictured here, along the route as cheap food for his labor force. By the time the railroad was completed in 1890, the train was used solely for transporting bananas. (THNOC, 1996.14.13)

The group visited quarantine hospitals and made an extensive tour of the Panama Canal, which the United States had recently purchased from the French in 1904. The photographs also document Central American people, dwellings, government buildings, and military bands. The photographs mostly show a large group of wealthy white men enjoying their time in a tropical paradise, but they also serve as valuable documentation of Central America during a pivotal moment in history.

A photograph shows some of the traveling party on the "quarantine island" off the coast of Bocas del Toro, Panama. The company chose to build some of its hospitals on small islands and peninsulas stretching into the harbors of their ports to protect the mainland against infection, much in the same way that there were quarantine stations on the Mississippi River to protect New Orleans. (THNOC, 1996.14.19)

The PR campaign was a massive success. When the party returned to New Orleans in February, the newspapers glowed with praise for United Fruit’s handling of its operations amid the epidemic: the company was “alive” to the sanitary conditions of Central America, the reports said, and southern states would work together to trace the source of the recent yellow fever outbreak. The fruit trade was deemed safe; United Fruit salvaged its reputation among the press, business community, and public opinion; and the port of New Orleans was permitted to resume accepting ships carrying cargo from Central America. The 1905 epidemic marked the final outbreak of yellow fever in North America, and thanks to the quarantine tour the United Fruit Company came through it relatively unscathed.

Women and children are shown standing outside of a hut near Belize, in what was then known as British Honduras, in 1906. (THNOC, 1996.14.64)

Over the following decades, the banana industry continued to grow both in New Orleans and abroad, with new competition and increased political power for United Fruit. In the 1920s, Standard Fruit Company, now Dole Food Company, was established in New Orleans under the leadership of “Ice King” Joseph Vaccaro and his two brothers. In the 1930s, the president of rival fruit company Cuyamel, Sam Zemurray, known locally in New Orleans as “Sam the Banana Man,” became the president of United Fruit and moved the company’s headquarters to New Orleans, where the edifice still stands at 321 Saint Charles Avenue. Much has been written about Zemurray, including his involvement in an overthrow of the Honduran government in 1912, as well as the 1954 CIA-backed coup d’etat of the democratically elected president of Guatemala, both to serve his business interests. In 1961, Zemurray lent steamships from the United Fruit’s “Great White Fleet” to the US government to be used in the Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba.

This group portrait shows hospital nurses at a United Fruit Company hospital in Belize in 1906, when it was known as British Honduras. (THNOC, 1996.14.50)

The legacy of these companies in Latin America is complicated, and United Fruit is often condemned for its selfish influence on the economies of these developing nations. The banana export business remains the primary industry of the countries visited on the 1906 quarantine tour, including Costa Rica, where Minor Keith is seen as a controversial historical figure. By the 1950s the Gros Michel banana crop was destroyed by disease, and it was replaced with the Cavendish (widely viewed as inferior-tasting), which is still shipped around the world today. Most historical accounts of the company either focus on its origins in the late 19th century or on its actions after Zemurray took over in the 1930s, so Teunnison’s photo album provides unique insight into an underexamined period of the company’s history.

The United Fruit Company building at 321 St. Charles Avenue is shown here in the 1920s. The edifice still stands but the headquarters were moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1985. (Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.869)

I see parallels today as businesses struggle to keep up with social distancing and masking guidelines and to stay profitable during the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, which has affected virtually every industry in New Orleans and around the world. Perhaps if United Fruit had had modern technology during the yellow fever epidemic, this photo album would have taken the form of a social media campaign. In 1906, business interests and global economics were the drivers for public health improvements in Central America, but they left painful legacies as well. Historical objects such as this one give us insight into possible effects of our choices today, as we struggle with similar challenges.