In the spring of 1942, Adolf Hitler brought World War II to Louisiana’s shores.

Over the course of that summer, German U-boats stalked defenseless tankers and transport ships in the effort to cut American oil supply lines through the Gulf of Mexico. In about a year’s time, more than 56 vessels were destroyed by the German Kriegsmarine, according to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

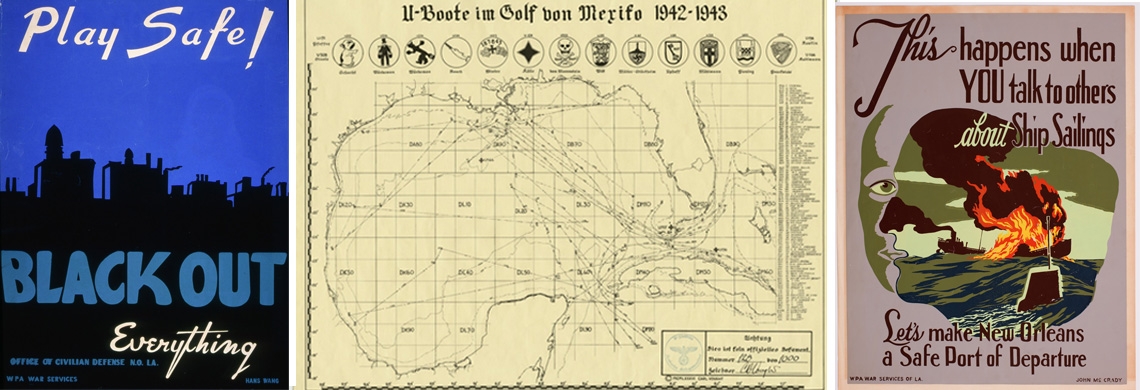

Carl D. Vought used historical information to recreate a map showing the positions of German U-boats in 1942 and 1943. The crosses denote locations where submarines were sunk. See it larger. (THNOC, gift of Carl D. Vought, 1991.156)

A map, based on historical information—on display in The Historic New Orleans Collection’s Louisiana History Galleries—shows how a fleet of more than 20 submarines freely crisscrossed the Gulf, picking off targets with ease. The marks on the map represent sunken or damaged ships, whose names are listed on the right side. The section of the map nearest the mouth of the Mississippi, marked “DA90,” was particularly dangerous.

During the height of attacks in the summer of 1942, coastal towns that brim with tourists and sportsmen today became drop off points for the dead. George Will—a sailor assigned to a minesweeping vessel—recounted in an oral history from New Orleans Goes to War, 1941–1945, that his crew would pluck victims out of the water and bring them to a dockside restaurant in Venice, Louisiana.

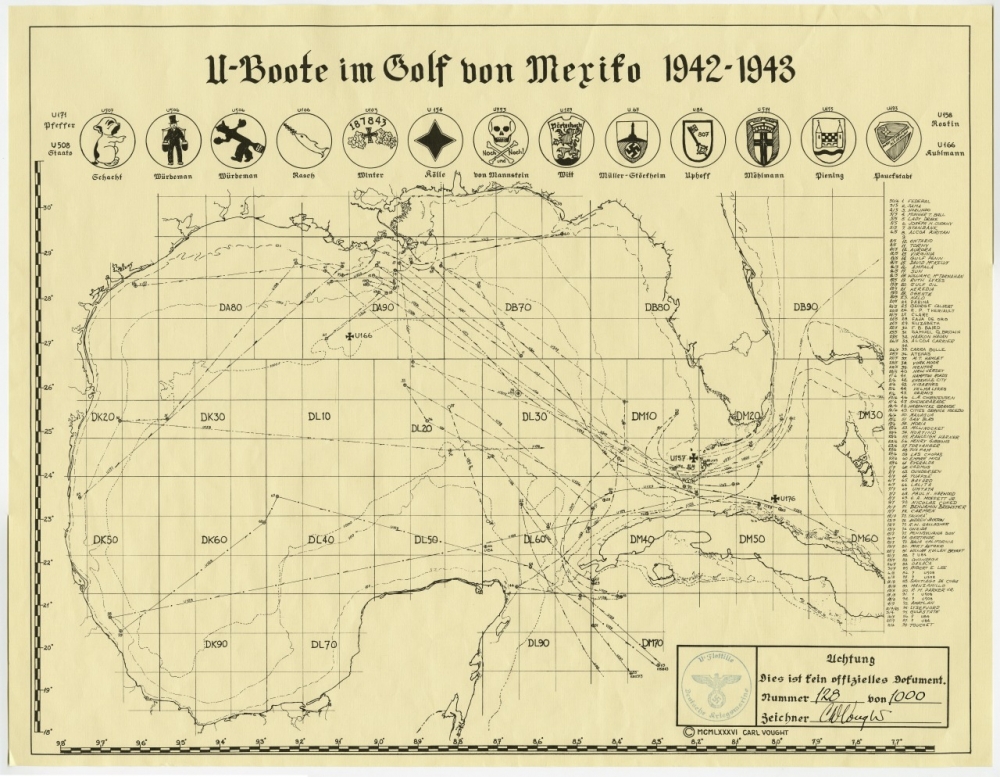

A poster by artist John McCrady admonishes citizens to stay quiet about ship sailings. (THNOC, 1988.99.2)

It was not until late 1942, when merchant ships traveled with military escorts, that the killing abated. However, until then, many vessels were doomed. Illuminated coastlines silhouetted ships, making them easy to see in the night. Slow and unarmed vessels became easy prey for the nimble U-boats.

Will remembered German captains’ bravado, surfacing after torpedoing a ship, and the hapless preparation by the navy—the converted yacht on which he served was only equipped with one large gun and a few depth charges.

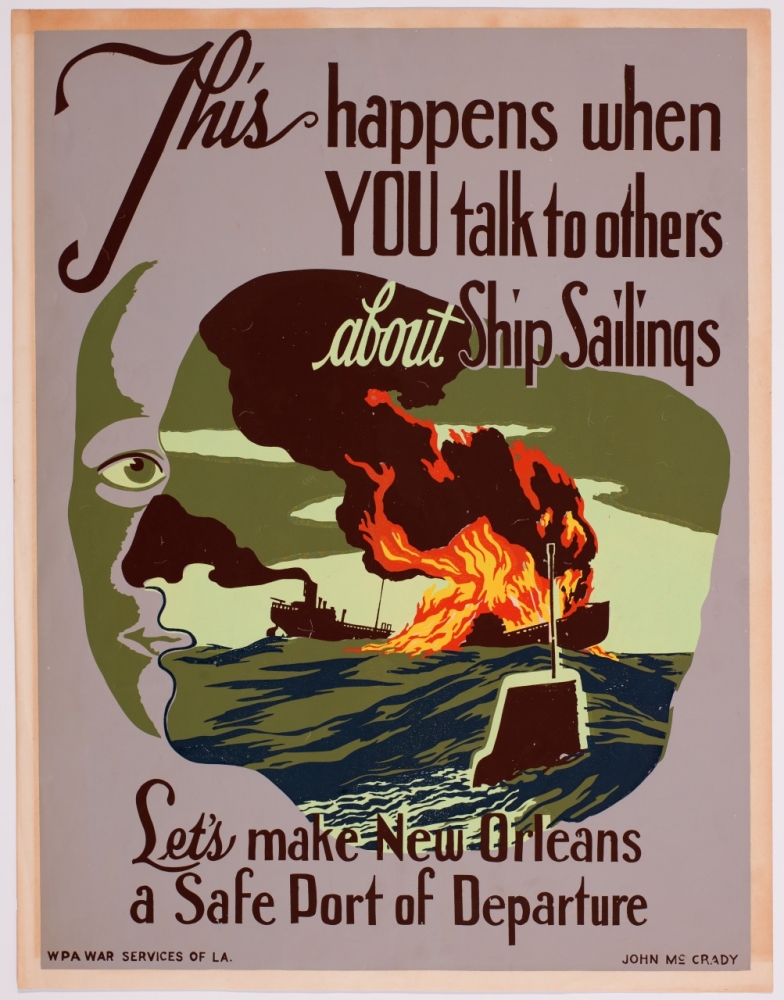

Eventually, blackouts and more heavily armed escorts ended the open season on civilian and merchant marine ships.

Illuminated coastlines made it easy for German captains to pick targets in the Gulf of Mexico. On the left, a poster urges citizens to black out their lights. On the right, a letter from Chief Air Raid Warden BC Moore notifies Antoine’s Restaurant that the business was in violation of blackout restrictions in March of 1942. (THNOC, the Anna Wynne Watt and Michael D. Wynne Jr. Collection, 1981.203.53 ii; THNOC, gift of Antoine's Restaurant, 2019.0439.23)

Perhaps the most notorious incident in the Gulf was the sinking of the Robert E. Lee, a civilian passenger ship, on June 30, 1942. The Lee’s escort, Navy boat PC-566, immediately dropped depth charges after the attack, but the small oil slick that appeared suggested that the crew had only damaged the U-boat, not destroyed it. According to the Navy Times, the boat’s captain, Lt. Cmdr. Herbert Claudius, was sent to anti-submarine school to improve his tactics. A couple of weeks later, a Coast Guard plane off the coast of Houma spotted a sub and dropped its own depth charge. A larger oil slick appeared—U-166 had been sunk.

However, geologists scanning the Gulf floor in 2001 found the felled German submarine close by the wreckage of the Lee, far away from its assumed resting place off of Houma. The submarine hit by the Coast Guard plane, it was discovered, was damaged but managed to escape. The US Navy corrected the error in 2014 and gave Claudius and PC-566’s crew credit for sinking U-166—72 years after it happened.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Historically Speaking column of the New Orleans Advocate.