The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, more commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, was established by President Abraham Lincoln in March 1865. The Bureau provided social and economic services to formerly enslaved people and others living in poverty throughout the southern states and Washington, D.C. These services included assisting African American veterans in collecting pensions and back pay, distributing essential goods, facilitating labor contracts between sharecroppers and landowners, and helping to establish and maintain freedmen’s schools. Copies of Freedmen’s Bureau records in The Historic New Orleans Collection’s holdings contain a wealth of information about Bureau activities—especially education initiatives—in Louisiana during Reconstruction.

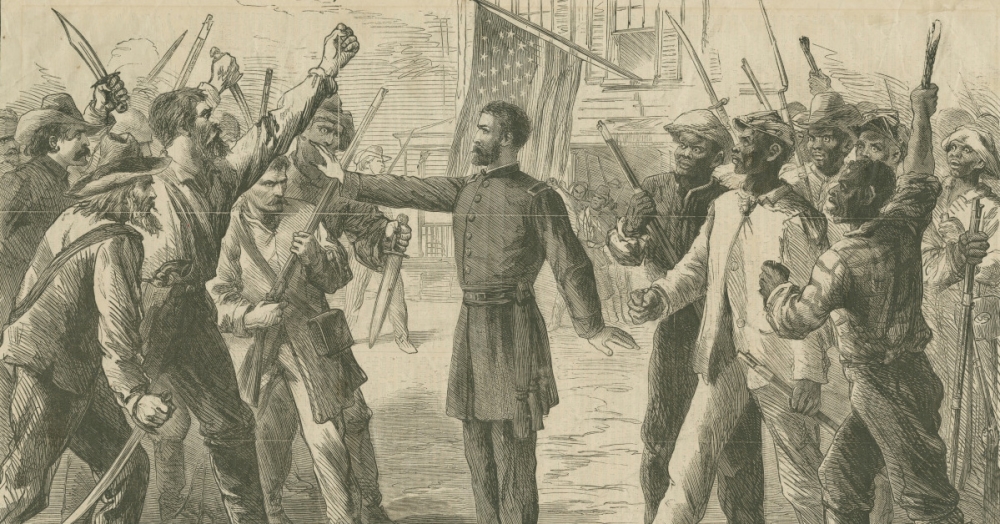

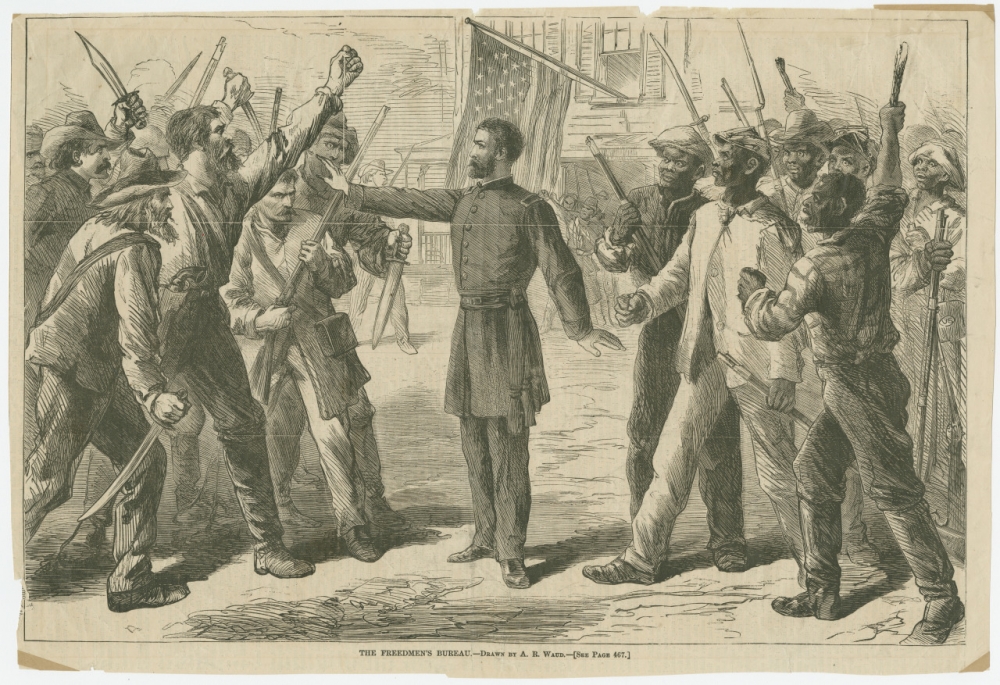

This drawing, simply titled "The Freedmen's Bureau," depicts a soldier separating black and white citizens. The Freedmen's Bureau was established by President Abraham Lincoln to provide aid for formerly enslaved people and others living in poverty in the southern US and Washington, DC. (THNOC, 1974.25.9.317)

In the post-war South, the demand for education of newly freed people was enormous, and Freedmen’s Bureau agents were instrumental in establishing schools for African American children and adults. Aaron Walker, one of these agents, wrote in an October 1865 report to the Bureau’s superintendent of education in Louisiana that he had helped to establish three schools in Shreveport and two in Natchitoches, both in northwestern Louisiana, each enrolling over 40 students. Walker commented that the number of potential students in the central Louisiana town of Alexandria could fill at least two schools, but there was no building, or even room, in which to house the school. Closer to New orleans in Jefferson Parish, an agent (whose signature on the report is illegible) reported that his district contained 13 schools, but that he may have to close at least two due to insufficient funding.

This anecdote and others in the agents’ reports struck at one of the largest obstacles to creating and sustaining schools: money.

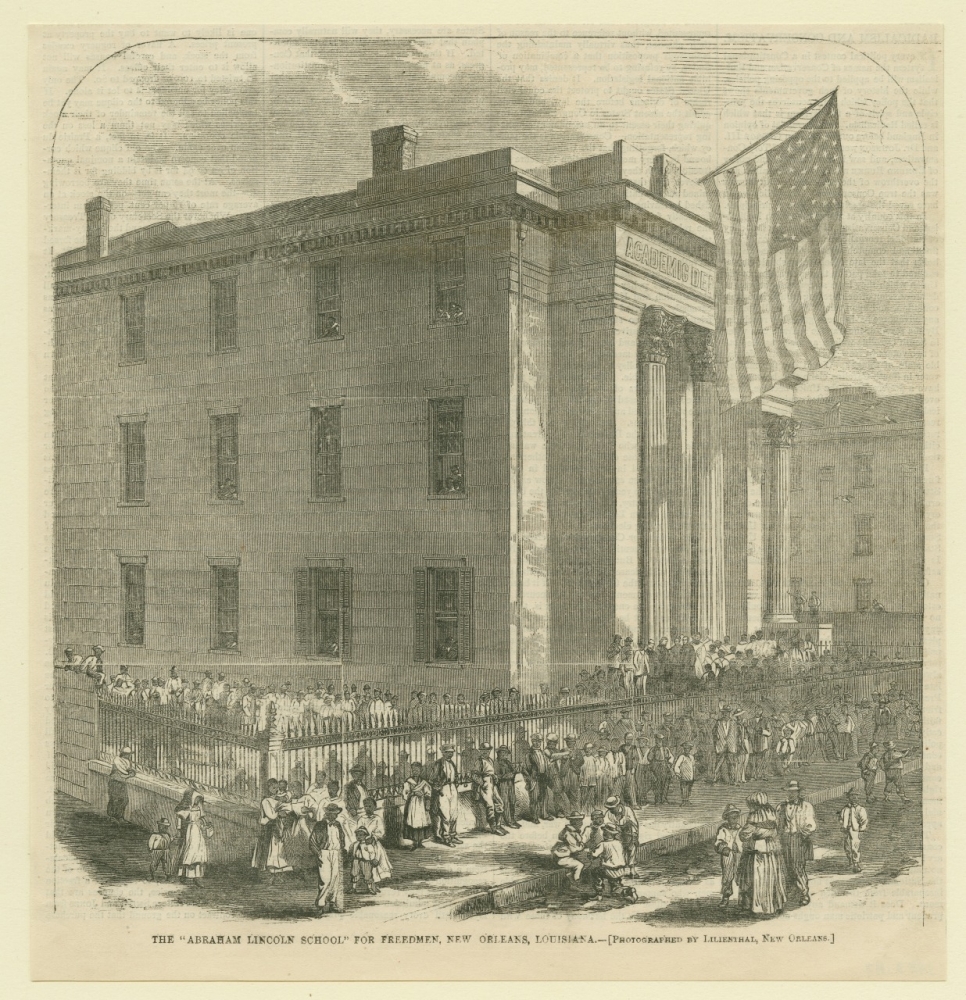

The Freedmen’s Bureau opened the Abraham Lincoln School in New Orleans in October of 1865 in a building formerly occupied by the University of Louisiana. This 1866 image was published on the cover of Harper's Weekly. (THNOC, gift of Harold Schilke and Boyd Cruise, 1953.82)

The Freedmen's Bureau had originally instituted a plan that required all Louisiana residents to pay a five-percent tax to support these schools, but many whites protested, so a system in which only freedmen paid the tax replaced it. This tax created an extra burden on an already impoverished populace, agents observed. Walker reported that the Shreveport and Natchitoches school buildings were obtained with no rent required, but George Ruby, another agent, who went on to become a prominent African American political leader in Texas, wrote of a different situation further east in Amite Station in St. Helena Parish. “There are a large number of freedmen in the vicinity working the sawmills and elsewhere, who are all willing to sustain and anxious about their schools,” Ruby wrote, “but the trouble is just now their people though laboring, have little means.” The Jefferson Parish agent noted that he had “reasoned and explained to [the laborers] the great necesity [sic] of Education,” but that many objected to paying a tax that wasn’t being universally enforced.

According to a report in Harper's Weekly, the Abraham Lincoln School in New Orleans, with a faculty of 14 teachers, enrolled more than 800 freedmen when it opened in October of 1865. Within six months, however, the school system instated a monthly tuition fee of $1.50, and the numbers of both students and teachers decreased by half.

In 1872 Congress failed to renew the Freedmen’s Bureau’s supporting legislation. White resistance to Reconstruction policies increased in the following years, leading to violent conflicts in Louisiana and the rest of the South. By 1876, when Democrats regained control in the South amid the fallout from a controversial presidential election, most Reconstruction programs, like the Freedmen’s Bureau, had become memories of post-war possibility.