Editor's note: This is a personal story by THNOC Associate Editor Nick Weldon.

I started feeling symptomatic on March 28. I ran 3.27 miles that morning, to the bayou and back. My usual route. Early morning runs have been a respite for me since this quarantine started. Later that day I started coughing a little bit, but not enough to frighten me. I haven’t run since that day.

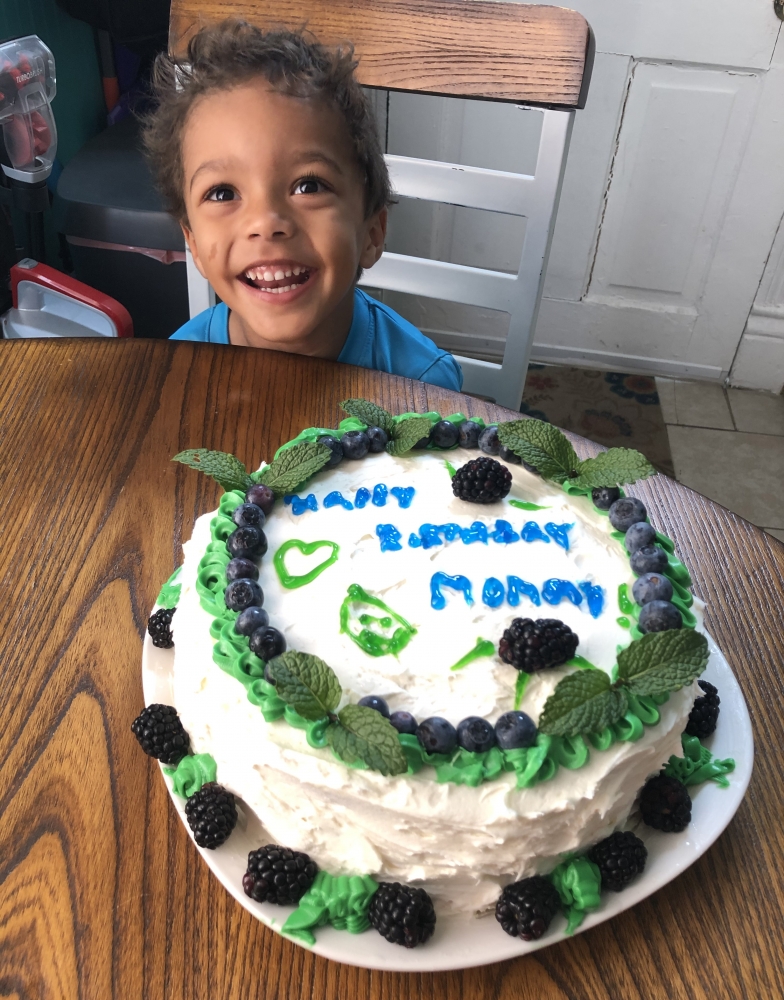

It had started with a cough for my wife, too, about 10 days earlier. She also developed a nagging earache. After those symptoms abated, she completely lost her senses of smell and taste. We weren’t sure what to make of that until we read an article about how those symptoms may be related to the coronavirus. My son and I baked a birthday cake for her (vanilla buttercream) that she couldn’t taste. We froze a big chunk for when her senses (hopefully) returned.

My son with my wife’s cake. (Image courtesy of Nick Weldon)

My son with my wife’s cake. (Image courtesy of Nick Weldon)

When I started coughing on March 28, I had reasons to be optimistic. My kids and I—notably, not my wife—had gotten sick in mid-February with COVID-19-like symptoms, and I had started to believe that we’d already had the virus during the peak of Carnival. I’d had a fever back then that wiped me out for about three days. This new thing might just be a cold, or allergies, I thought. The next day when I woke up with a froggy throat, I still didn’t make much of it. After a cup of coffee, I didn’t even notice it anymore. In fact, I got the charcoal grill out and cooked our dinner in the backyard. Of course, the smoke triggered the cough again. That was so dumb of me.

That night, the fever started. Mild, at first, a hair above 100. I took Tylenol to manage it that night and throughout the next day. The second night was much worse. The fever was steadily above 102 and I had one reading north of 103. The next day—Tuesday, just over a week ago—my wife and I decided to load the kids into the car and go get drive-through COVID-19 tests at the UNO Lakefront Arena. We sat in a line of cars, stretching from the arena parking lot well down Franklin Avenue, for almost four hours. We didn’t bring enough snacks or diversions for the kids (a four-year-old and a ten-month-old), and by the time we finally got to the medics in the hazmat suits with the giant swabs the baby was crying at a decibel I’d never heard in my life. The discomfort of the probe fishing around in the back of my throat was somehow a welcome distraction.

The COVID-19 testing line at UNO. (Image courtesy of Nick Weldon)

We had friends who had been waiting on their own results for well over a week, so we weren’t optimistic that we would get ours in time to make a difference if our own conditions worsened. But at least, we felt, we’d contributed to somebody’s data set. By the next morning—Wednesday, April Fools Day—my fever had broken, and I allowed myself to believe that the worst was over. I was dog-tired and couldn’t smell or taste anything (still can’t), but I felt like I was on the mend. My wife had most of her smell and taste back and got to enjoy a slice of her birthday cake, finally. The kids were fine. We were going to be OK.

I rested for the better part of two days. Saturday morning (six days ago) I felt well enough to dig into the batch of illustrations I’d just received for the graphic novel I’m editing for THNOC. It’s called Monumental, about the life of Oscar Dunn, America’s first black lieutenant governor, and I encourage you to read it when it comes out in February. It’s an incredible story about a civil rights pioneer cut down in his prime—by a sudden and mysterious illness, no less. But I digress. While I was editing, my wife and I both got calls confirming that we tested positive for COVID-19. A four-day turnaround—much better than we’d expected, confirming a diagnosis we’d already more or less accepted. But we both felt fine, so I got back to work. I spent most of the day reviewing the artwork, and then took my son out into the backyard to hit the baseball around. One of our quarantine rituals.

Our routine is that I pitch a little foam ball to him, he hits it with a little foam bat, and I go fetch it—which is especially fun for him when he knocks it over the neighbor’s fence, which he does with alarming frequency. About 20 minutes in, I started feeling short of breath. My chest felt tight, and it almost felt like I was sucking air through a straw. We ended our session abruptly, and I went inside to sit down. Maybe I’d overdone it. But after a few hours had passed and I was still having trouble breathing, I called my doctor. It was after-hours, so I spoke to an on-call physician, who recommended that I go to the emergency room.

What followed was one of the hardest conversations I’ve ever had with my wife. I didn’t want to be irrational, but I’d read the stories. People go into the hospital with this thing and never see the light of day again. Never see their loved ones again. Die alone. We’ve all been inundated by these horror stories for weeks, and in that moment I couldn’t help but wonder if that was going to be my story. I cried. She cried. My son ran into the room and asked what was wrong. He has a vague sense of the virus that’s cancelled school and swim classes and kept Mommy and Daddy home for weeks, but he’s only four. I got myself together long enough to give him a huge hug and tell him I loved him. I think he squirmed away awkwardly—I don’t know, it’s all a blur now. We piled into the car and drove to the Touro ER. I hugged my wife for a long moment, said goodbye to the kids, and walked in by myself.

It was about 9 p.m. on Saturday night. The ER was eerily quiet, and the nurses were shockingly upbeat. Within seconds of explaining that I was having trouble breathing, they whisked me into a bed—no wait time. They took my temperature, checked my oxygen saturation levels, and performed an EKG within a matter of minutes. Everything was looking good. Then they had to insert an IV and draw blood to test some other stuff. I told them I’d passed out during blood tests before and the words had barely left my mouth before I was unconscious—or at least that’s how I remember it. I woke up in a state of utter confusion, my head shaking and my brain not processing the people in the scary masks surrounding me. There was now oxygen hooked up to my nose, and I was sweating profusely. It felt like I’d been out for hours but I’m sure it was a matter of minutes. When I finally came to my senses a funny nurse muttered, “Well, he did warn us.” I was wildly nauseous, and they gave me something through the IV for that, though it took a while to kick in. My oxygen saturation was back up, so they took the tubes away. Next came the chest X-ray. After that, I waited about 15 minutes for the doctor to return with the results. He came in with the best news I think I’d ever heard: “You look good.” I had some mild lung inflammation that’s typical of upper respiratory illnesses, but I was safe to go home. He said I did the right thing coming in, and shared that he had also had COVID-19 and experienced breathing problems similar to my own. He recommended some over-the-counter medication to manage my symptoms, and said I was free to go. Back home. Back to my family. I was in and out of there in less than two hours. I cannot speak highly enough of Touro ER team—they were professional, caring, and thorough in the most stressful of settings. When my wife picked me up, with the kids asleep in the back seat, I hugged her and cried again. That night, I slept like a baby.

My first visit to the Touro ER. (Image courtesy of Nick Weldon)

Sunday morning, I vowed to stay in bed all day and binge-watch some TV shows that I hadn’t caught up on yet. I had control of my breathing—and though I felt tired, I knew I wasn’t feeling worse. But then my phone rang. A different doctor from the ER. She said she had consulted with a radiologist and had discovered some abnormalities on my X-ray from the day before. She wanted to bring me back for more tests. She was concerned that I might have a mass in my throat, down near my clavicle. It could also have been a bad angle on the X-ray, but she wouldn’t know for sure without more X-rays and possibly a CT scan. Wait, what? A mass in my throat??

My head spinning, I put the doctor on speakerphone to explain the situation to my wife. We were both in shock, but back to the ER we went. It was much busier on Sunday. I got a new set of X-rays rather quickly but had to wait a long time for my CT scan. Shortly after I got there, an unresponsive man in his 70s was wheeled into the bed next to mine, on the other side of the curtain. Within a short amount of time they had somehow determined that he had COVID-19. He couldn’t speak for himself, and for the next several hours I listened to him cough mercilessly and struggle to breathe. A woman in her 60s was brought in next to him, and I could hear her gasping for air as she explained to family members on the phone what was happening. She, too, tested positive. A Sharknado marathon played on the TV over my bed. It was awful.

People come into the hospital to check one thing, and discover something entirely different. You hear about it all the time. For hours, I lay in bed trying to push away the scary thoughts—the other C-word. Rationalizing. I’m 32. I’m healthy—relatively. I can handle this. It could be so much worse. My poor neighbors in the beds next to me. The man who couldn’t talk. The woman trying to explain a dire medical situation to family members on FaceTime. Just get me out of here and we can figure this out, I kept saying to myself.

I finally got the CT scan. The iodine injection felt warm and uncomfortable, like my veins were lighting up all the way from my right arm to my head. The big tube and its robotic voice telling me to hold my breath felt dystopian. It was a short process and I was grateful when it was over. Soon, the doctor who called me in was at my bedside with the results: normal. “So what do you make of the abnormality on the first X-ray?” I asked her. I think she shrugged. She gave an explanation that made sense and assured me that my throat was clear. No mass. No cancer. After she left my bedside I cried again.

I paced outside the ER waiting on my wife and kids to pick me up, breathing the fresh air. Amid all this terror, at least we’ve had great weather, right, New Orleans? Six hours after dropping me off, they pulled up to the same spot, and I hugged my wife like we’d done the day before. Our new ritual. I didn’t have any tears left. I just wanted to go home.

The following day was fine. My lungs felt no better, but also no worse. My goal was to avoid the ER a third straight day, and I did. Tuesday morning, I woke up around 4:30 a.m. in a state of panic. I had a vivid dream about being inside a large barn with printing equipment and an elaborate speaker system, and suddenly I was struggling to breathe. I was shaking like I had chills, but I had no fever. I guess it was a panic attack. I’ve never had one before, but that’s what it felt like. My incredible wife, enduring all of this with me, helped me calm down. Slow breaths. In and out. I fell back asleep. She didn’t.

My family enjoying the backyard. (Image courtesy of Nick Weldon)

My family enjoying the backyard. (Image courtesy of Nick Weldon)

The days since have been more of the same. I wake up expecting to return to normal, but still feel that tingle in my chest that reminds me the virus isn’t gone yet. Stress turns the tingle into a tightness, and then a vicious anxiety cycle begins. When I’m distracted by a good show or a long drive around town (a new ritual that doesn’t exhaust me), I almost feel like myself. But I’m not there yet.

I didn’t write this to gain sympathy. There are so many people faring so much worse than me with this illness. People we know. The people whom I crossed paths with in the ER. I remember their names. I hope they’re getting better. I didn’t write this because THNOC is asking for #nolacorona content, either. We’re living through a historic moment. A tragic moment. Part of me does feel an urge to document my experience, to write it down while I still have the energy. If that lines up with the mission of the history museum I work at, all the better.

But mostly, I think, I just needed to get all of this off my chest. Writing has been cathartic. I’m taking it day by day, enjoying my family and the weather and whatever else takes my mind off of the crisis unraveling all around us. I’m appreciating small moments of peace. One morning soon, I hope, I’ll wake up and get this other thing off my chest, too.

#nolacorona

We want to hear about your life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Use #nolacorona in social media posts to share your stories from everyday life. Public tweets using the hashtag will be archived. For more on our efforts to collect material related to this crisis, read out recent First Draft article.