For all its many traditions, New Orleans Carnival has always been a ready canvas for innovation and innovators. The contemporary celebration of Mardi Gras owes its form in large part to Anglo-American businessmen who in 1857 organized the Mistick Krewe of Comus, adding a degree of formal organization to the pre-Lenten period that had been observed by the city’s Creole population with bals masqués, bals du roi, and masked processions of revelers in the streets.

Beginning in the 1890s in New Orleans, the association between the presentation of the year’s debutantes and the season’s Carnival balls became firmly established. The 1890s was also a period when the political and social possibilities of the Reconstruction period increasingly gave way to the legally enforced Jim Crow system. Into the world of fin-de-siècle New Orleans came Carnival innovator Wiley James Knight, a 22-year-old Black native of rural Bolivar, Tennessee, who according to legend had been employed at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and came to New Orleans in the employ of the wealthy Charles Morgan family.

In the years preceding Knight’s arrival, New Orleanians of color had celebrated with balls and “King and Queen” dances, primarily in society halls, such as those of the Jeunes Amis and Économie societies in the downtown section, and Geddes Hall and St. Elizabeth’s Hall Uptown. It was likely in St. Elizabeth’s Hall on Camp Street, near Cadiz Street, that Wiley Knight began offering dance lessons to young men and women of color in 1894. In 1895 his students decided to hold a Carnival ball, which was held in the Globe Hall (located in part of what is now Armstrong Park and destroyed by fire in 1918).

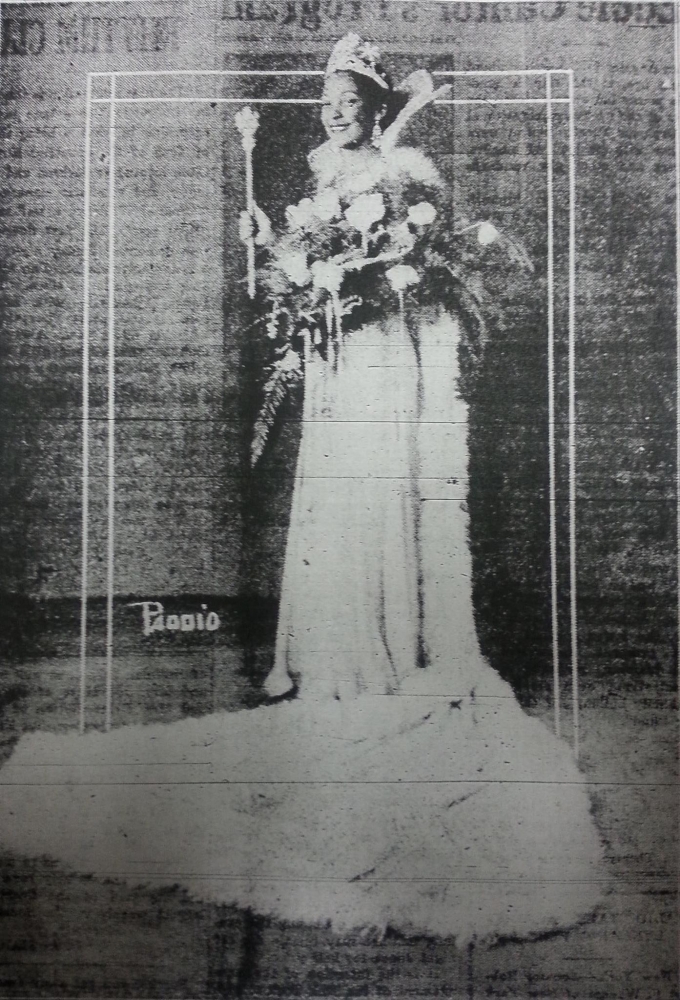

Doris Gaynell Taylor reigned as queen of the Original Illinois Club in 1936. (photograph courtesy of Creolegen.org)

The first queen was Miss Louise Fortier, a young seamstress from the Uptown section, who later married and migrated to Chicago. The young ladies that year represented “Music,” while their escorts were dubbed “Othellos.” Some of Knight’s students formed the Original Illinois Club (simply called the Illinois Club until 1926), which remains the oldest Black Carnival club in the city. It had male and female members until roughly 1900, when the club became male-only, as are most traditional Carnival organizations to this day.

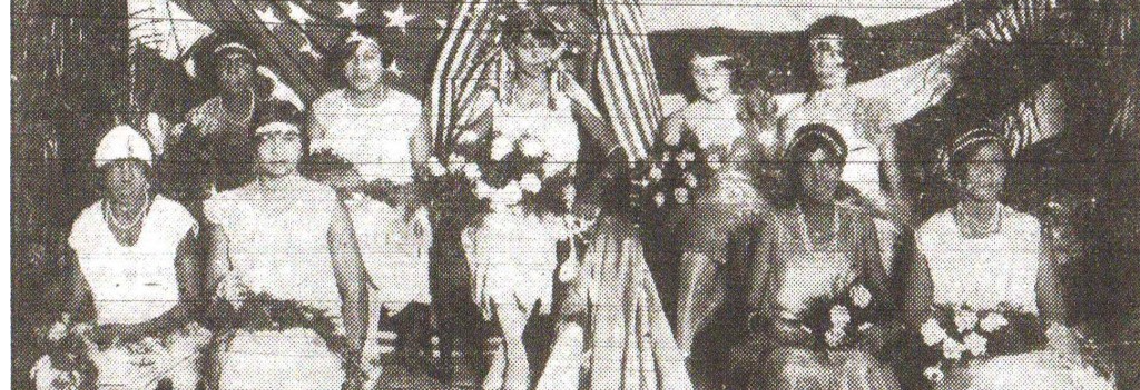

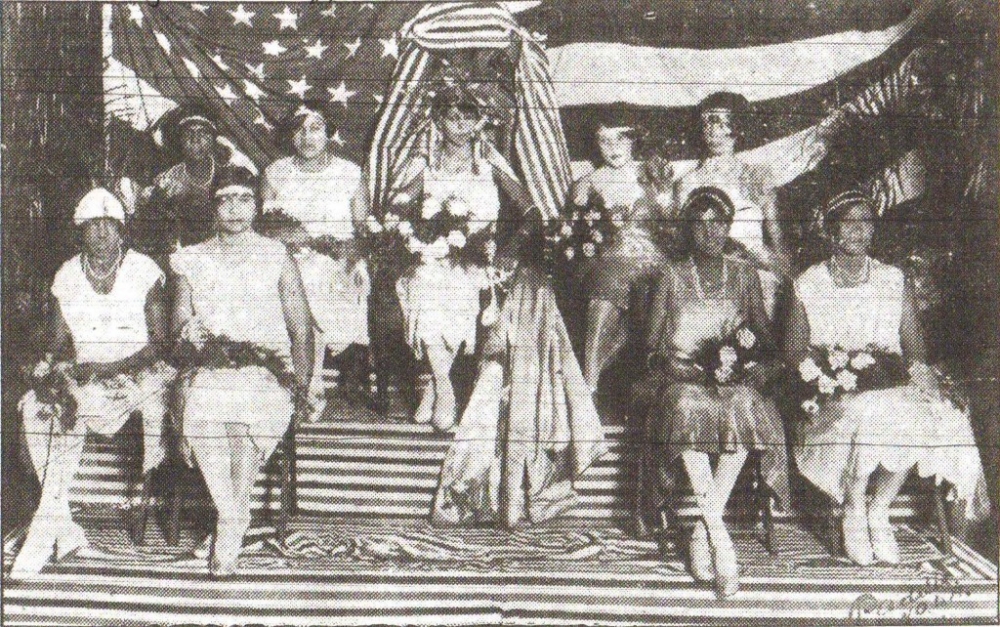

The 1927 debutantes of the Young Men’s Illinois Club ball. Back row (left to right): Virginia Gibson, Alice Baptiste, reigning queen Mabel Saulsby, Inez Alston, Eloise Clark. Front row: Amy Bloom, Katherine Dupre, Ophelia Baptiste, Valeria Barnes. (photograph courtesy of Creolegen.org)

In many ways, the founding of the Original Illinois Club and its presentation of debutantes was a conscious response to the burgeoning Jim Crow system. It was a declaration that people of color were imbued with the same refinement and social graces as the white New Orleanians whose organizations presented their own debutantes each year.

Though there were as many as 100 Black clubs hosting Carnival balls at the practice’s high point in the 1960s and ’70s, the number of them incorporating debutantes has always been comparatively few. In addition to the Original Illinois Club, there is its friendly rival, the Young Men’s Illinois Club, an offshoot formed in the spring of 1926, the result of a disagreement long shrouded in Carnival mystery.

Program for the 1976 Original Illinois Club Mardi Gras ball. Marcus Neustadter, Jr. (designer). (THNOC, 1976.66.28)

The Capetowners followed in 1935 and the Beau Brummels in 1940. Two of the city’s earliest Black parading organizations, both of which still take to the streets, NOMTOC (“New Orleans’s Most Talked of Club,” est. 1951) and the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club (est. 1909), also present debs at their balls. Though most of the clubs are made up of men, in the past there were a few women’s Carnival clubs, including the Original Exclusive Twenties and the Royal Dynamics, which also presented debutantes.

While the men, smartly attired in white tie and tails, are the club members, it is clear that the young ladies are the centers of attention. For the debutantes, their presentation marks their symbolic entry into society. It is an indication that they have been sponsored by a club member and mentored by the ladies affiliated with the club. First preference for new debutantes is given to the daughters and granddaughters of members.

Donna Marie Darby, daughter of Clarence J. Darby and Betty Cloud Darby, made her debut with the Original Illinois Club in 1980. (gift of Christopher Porché West, THNOC, 2000.30.12; © Christopher Porché West)

The presentation at the ball is the culmination of a nearly year-long cycle in which the young ladies are schooled in court etiquette and introduced to club members and guests through afternoons of high tea and deb parties, which their families host in lavish style in halls and hotel ballrooms throughout the city. For the debutantes of the Original Illinois Club and the Young Men’s Illinois Club, their preparation includes dancing to the strains of the “Chicago Glide,” a Romantic dance tune published in 1894, just after the popular 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Its familiar strains are a poignant musical memory for the debs, their member-escorts, and guests. Always in attendance are several former debs and past queens, and in many cases, there are several generations of Carnival royalty within the same family.

The balls are not only showplaces for the women, but also for the modistes, as they are called—the expert dressmakers, whose masterpieces shine and glimmer beneath the ballroom lights. The names of these modistes, such as Marceline Taylor, Durelli Watts, and Marigold Hardesty, become bywords in the Carnival world. It is not uncommon for mothers to bring their daughters to be fitted by the same talented hands as they were decades before.

Delores Baranco reigned as queen of the Original Illinois Club in 1937. (Louisiana Weekly, 1937)

In recent decades, some have called into question the value of the debutante tradition and the investment of time and money it entails. There are people, particularly outside of New Orleans, who might see the tradition as reinforcing outdated gender roles, but it endures as a unique intergenerational coming-of-age ritual. Former Young Men Illinois president and educator Luther Young said, “Maybe it’s a rationalization, but bringing girls out at their best in society added purpose to their womanhood.”

This unique coming-of-age tradition is a reminder to the young ladies that they have the cross-generational support of an entire community urging them onward to reach their fullest potential and to enable themselves to give back to others. It is a once-in-a-lifetime experience that has launched the public lives of so many women who have entered professional, philanthropic, civic, and social worlds with poise, grace, and an appreciation for the recurring magic that is Carnival.