In late January and early February of 1815, people in cities throughout the United States daily expected the news that New Orleans, the country’s most important western port, had fallen to the enemy. Few believed that a small American force could prevail against the veteran British army that had burnt the US Capitol the previous summer. So when reports of a lopsided American victory began to spread up the Atlantic seaboard in early February, the country rejoiced. Bells rang, people cheered, and newspapers could not be printed quickly enough. Everyone wanted to see and know more about the victorious American general from Tennessee.

Unfortunately for the public, and for the artists poised to satisfy their demands, almost no one knew what Andrew Jackson looked like beyond the handful of people who had met him in person. From 1815 to 1819, most of the images of Jackson that were widely available in prints, souvenir objects, and books were derived from two early portraits of Jackson that were made in New Orleans within weeks of the battle. The two works were very different from each other, and neither was a good likeness. The historian James Barber carefully traced the lineages of these various early likenesses in his 1991 study of Andrew Jackson portraiture. It was not until the winter of 1819, after his service in the First Seminole War, that Jackson sat for accomplished portrait painters who captured the famous general as he actually appeared.

Major General Andrew Jackson

ca. 1818; oil on canvas

by Nathan W. Wheeler, painter

The Historic New Orleans Collection, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 2008.0208.1

In creating this painting, Nathan W. Wheeler (ca. 1790–1849) copied his own original 1815 rendering of Jackson, painted from life soon after the Battle of New Orleans. Many popular early likenesses of the famous general were based on Wheeler's portrait, which exaggerated Jackson's nose and other facial features. The artist may have emphasized the general's gauntness to reflect his poor health during the crisis.

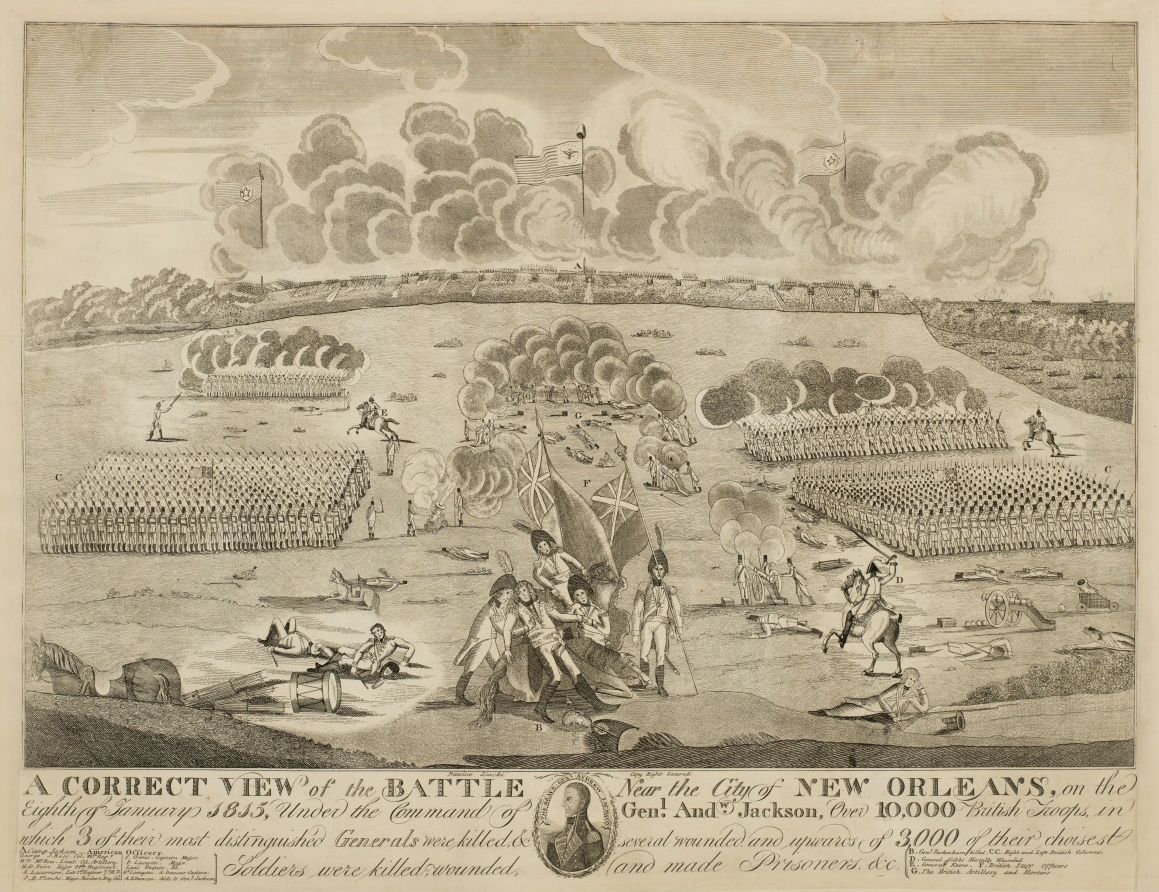

A Correct View of the Battle Near the City of New Orleans . . .

between 1815 and 1818; aquatint, engraving, and etching

by Francisco Scacki, engraver

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1948.2 i–iv

One of the earliest printed views of the famous battle, this engraving places the Mississippi River on the wrong side of the battlefield and includes a portrait of a generic American officer as a stand-in for Andrew Jackson. The artist had never seen the famous general or visited Louisiana.

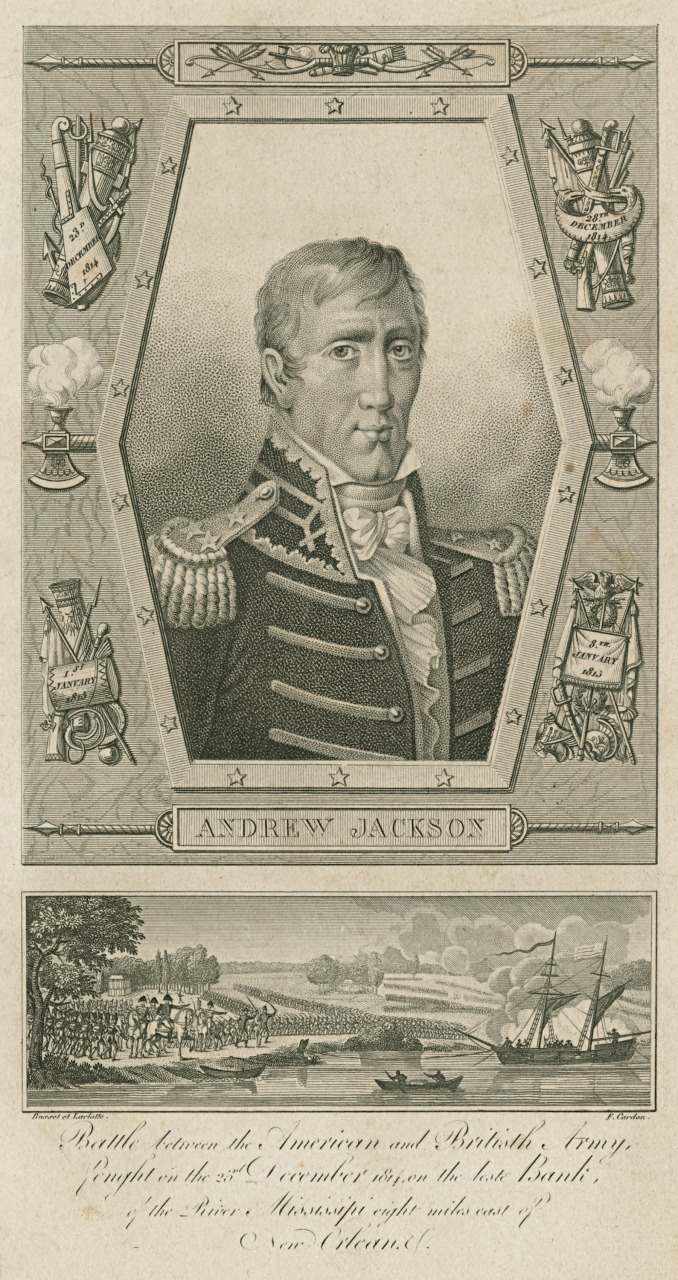

Andrew Jackson / Battle between the American and British Army . . . 23rd December 1814 . . .

between 1815 and 1817; engraving

by G. Busset, artist; Jean Hyacinthe Laclotte, artist; F. Cardon, engraver

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1957.121 i,ii

This engraved portrait, produced in Paris by Madame G. Busset, suggests that Jackson may have been an object of curiosity for the French public, so recently humiliated by their emperor's defeat at the hands of a British-led coalition. The accompanying view by Laclotte (1765–1828) shows the first land battle between US and British troops, on the night of December 23, 1814.

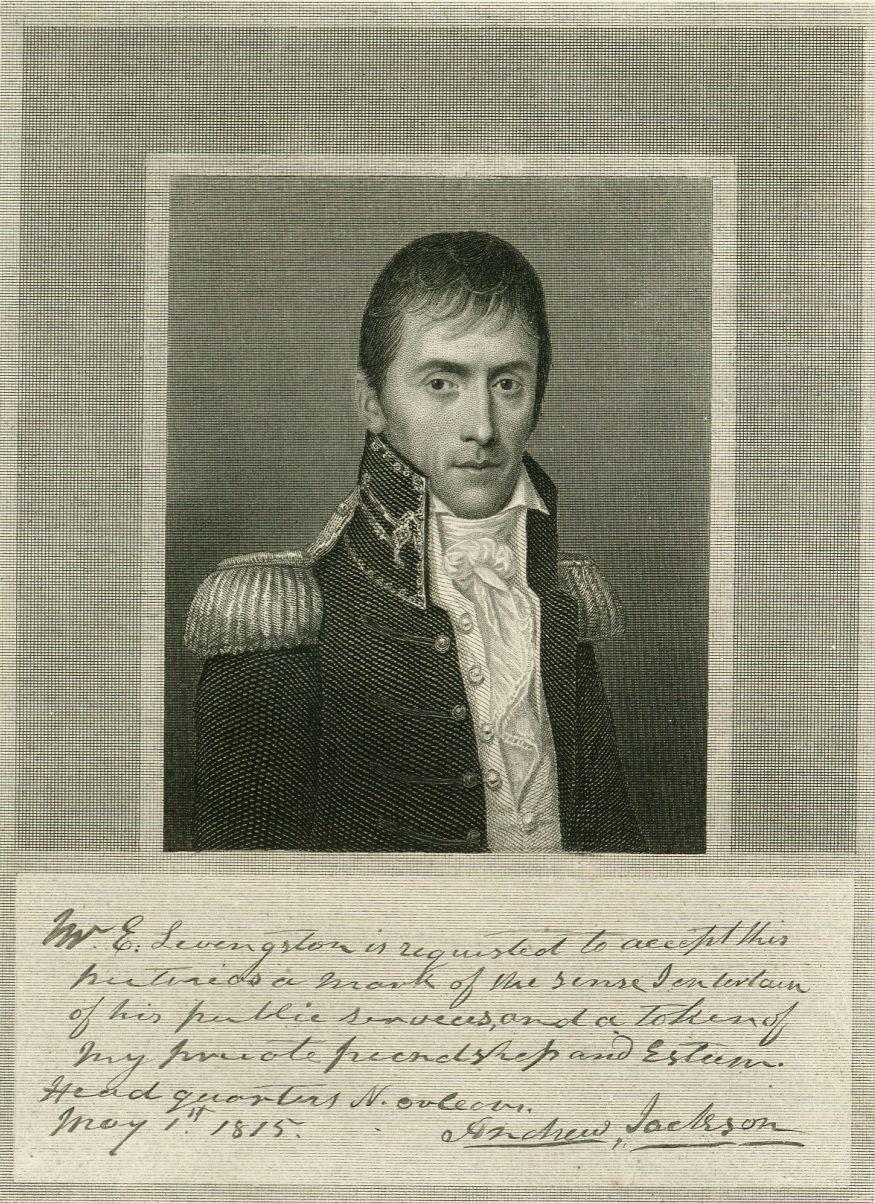

Copy of an 1815 Andrew Jackson portrait miniature and note from Jackson addressed to Edward Livingston

ca. 1864; engraving

by Alexander Hay Ritchie, engraver, after Jean-François Vallée, artist, and Andrew Jackson, author

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2008.0226.1

Jean-François de Vallée (b. 1775), a French-born miniaturist active in New Orleans from about 1808 to 1818, painted Jackson as a strong, handsome young man. The general made a gift of this portrait and written inscription to his aide-de-camp Edward Livingston, and only a handful of people would have seen it. The likeness is flattering but not realistic.

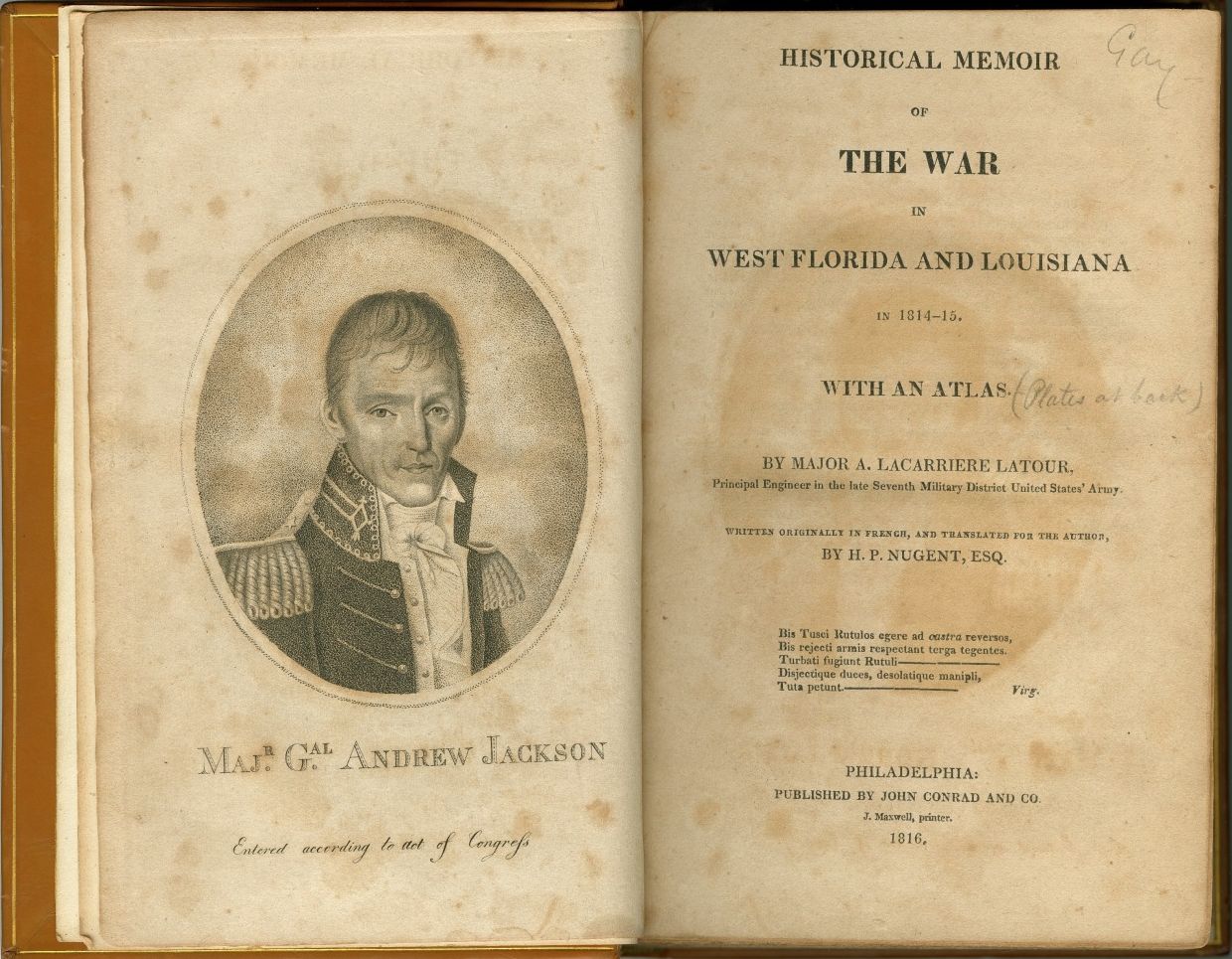

Historical Memoir of the War in West Florida and Louisiana in 1814–15

by Arsène Lacarrière Latour, author

Philadelphia: John Conrad and Company, 1816

The Historic New Orleans Collection, bequest of Richard Koch, 71-62-L.7

The first published history of the Battle of New Orleans, written by Jackson's chief engineer, Major Arsène Lacarrière Latour (1778–1837), included a frontispiece crudely engraved by Latour after Jean-François de Vallée's miniature portrait. Edward Livingston dismissed it as "a vile Caricature."

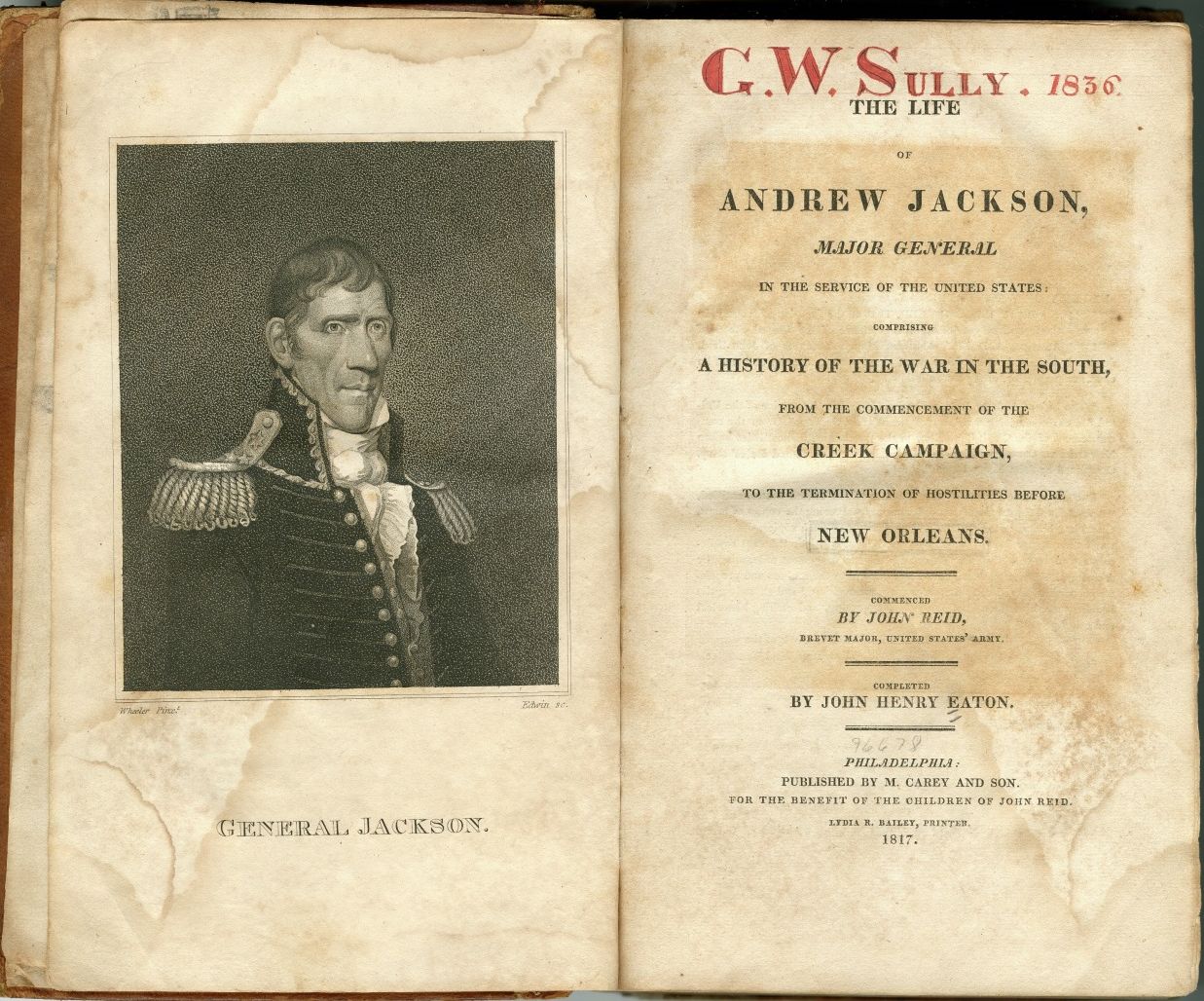

The Life of Andrew Jackson, Major-General in the Service of the United States . . .

by John Reid, author; John Henry Eaton, editor

Philadelphia: M. Carey and Son, 1817

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Dr. Patricia Brady, 2000-41-RL.1

The first biography of Jackson was penned by his friend and aide-de-camp John Reid and was finished by John Henry Eaton after Reid's untimely death. The first edition's engraved frontispiece by David Edwin (1776–1841) was based on Nathan W. Wheeler's portrait. An 1824 edition of the book used a different, more flattering frontispiece image.

Andrew Jackson snuffbox

ca 1820; black enamel over papier-mâché, with an attached engraving

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2006.0312

This snuffbox, believed to have been made in England, is decorated with a portrait of Jackson in uniform and an inscription above and below the image: "Major General Andrew Jakcson / Buttle of New Orleans, 8th Jan[u]. 1815." The misspelling of "battle" may have been intentional.

Andrew Jackson snuffbox

ca. 1820; papier-mâché with hand-painted engraving

The Historic New Orleans Collection, acquisition made possible in part by William C. Cook, MSS 557, 2014.0249.3

The printed portrait of Jackson on this snuffbox appears to be an engraving that was then hand painted. Though the source of the image is unknown, the portrait may have been derived from Nathan W. Wheeler's early likeness of the general.

Major General Andrew Jackson

1819; oil on canvas

by Samuel Lovett Waldo, painter

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1979.112

After the Seminole campaign of 1818, Jackson traveled to Washington and toured the East Coast. He sat for the artist Samuel Lovett Waldo (1783–1861), a successful portrait painter who painted in Charleston, London, and New York City. Waldo's portrait of Jackson was among the first artistic likenesses to show the famous general as he actually appeared.