Little in Andrew Jackson’s boyhood in the Carolinas would have indicated that he was destined to become one of the most powerful and influential figures of his time. Born in 1767 to landless Northern Irish immigrants and orphaned by the ravages of the Revolutionary War, young Andrew applied himself to the study of law before saddling up and heading west to seek his fortune, as hundreds of others like him were doing. As the historian Thomas P. Abernethy observed, “on the frontier a gentleman was a man who could play the part, and Jackson played the part convincingly.” While working as a lawyer and as a judge in the territory that would become the state of Tennessee, he attracted the attention and support of the powerful territorial governor William Blount and entered the political arena.

Though Jackson served in the US Senate in the late 1790s, he did not find real acclaim until later in life, after he had transitioned to a career as a militia major general. Newspaper accounts of the Creek War of 1813–14 introduced his name to a national audience. But it was his unexpected victory at the Battle of New Orleans in early 1815 that thrust Jackson into both the public consciousness and history. He became the “Hero of New Orleans,” a national symbol of an emerging American empire.

It has been said that societies often create the mythic symbols they need. Andrew Jackson was just such a figure: a man whose personal charisma, ambition, and accomplishments accorded with the wishes of thousands of Americans seeking new opportunities for themselves in the South and West. Common men could identify with Jackson the farmer and soldier, whose troops had nicknamed him “Old Hickory” on account of his toughness. His restless determination to win the West set the tone for the decades of expansion and development that followed and made him a powerful symbol of American resolve and self-sufficiency. But for others, Jackson’s rapid rise into power represented a threat to the established order. The prospect of an uncouth frontiersman directing the nation’s destiny was anathema to many, especially to the old, established families of the Northeast. Inspiring fervent adulation as well as hostility, Jackson left a lasting mark on the history and culture of the country at a time when its identity was still forming.

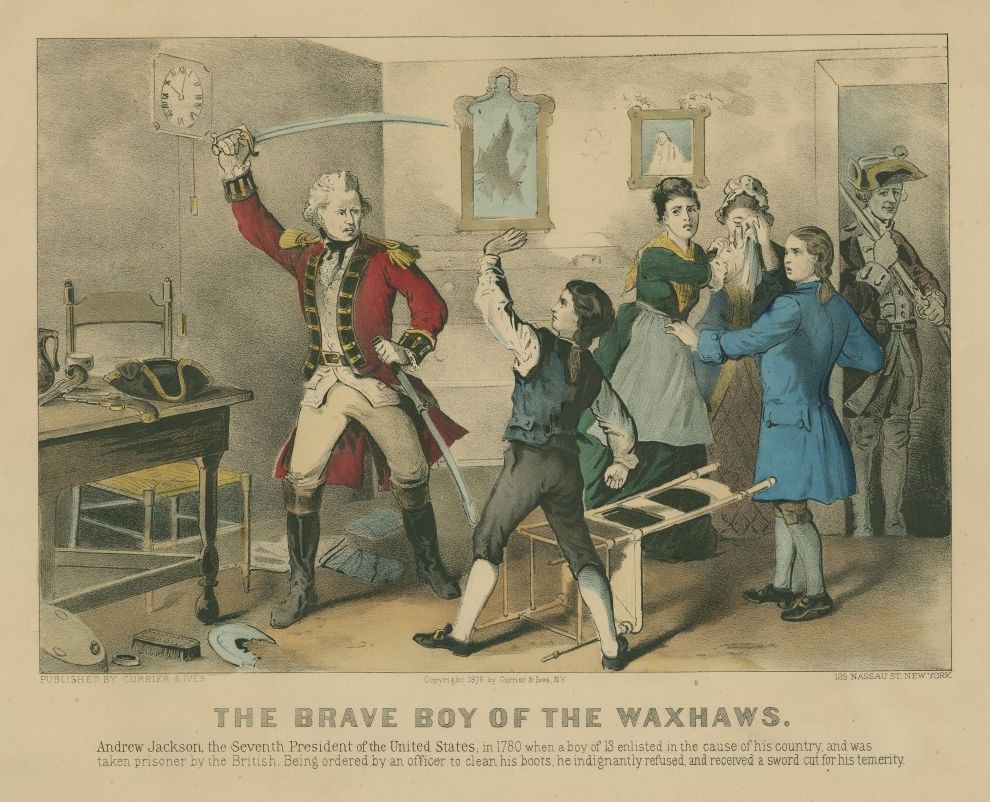

The Brave Boy of the Waxhaws

1876; hand-colored lithograph

by Currier and Ives, publisher

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1963.22

This popular view dramatizes a Revolutionary War incident wherein a British army officer, outraged by young Andrew Jackson's refusal to polish his boots, slashed the boy's hand and head with a saber. Years later, a friend of Jackson's claimed that he could lay his finger in the dent that remained in Jackson's skull.

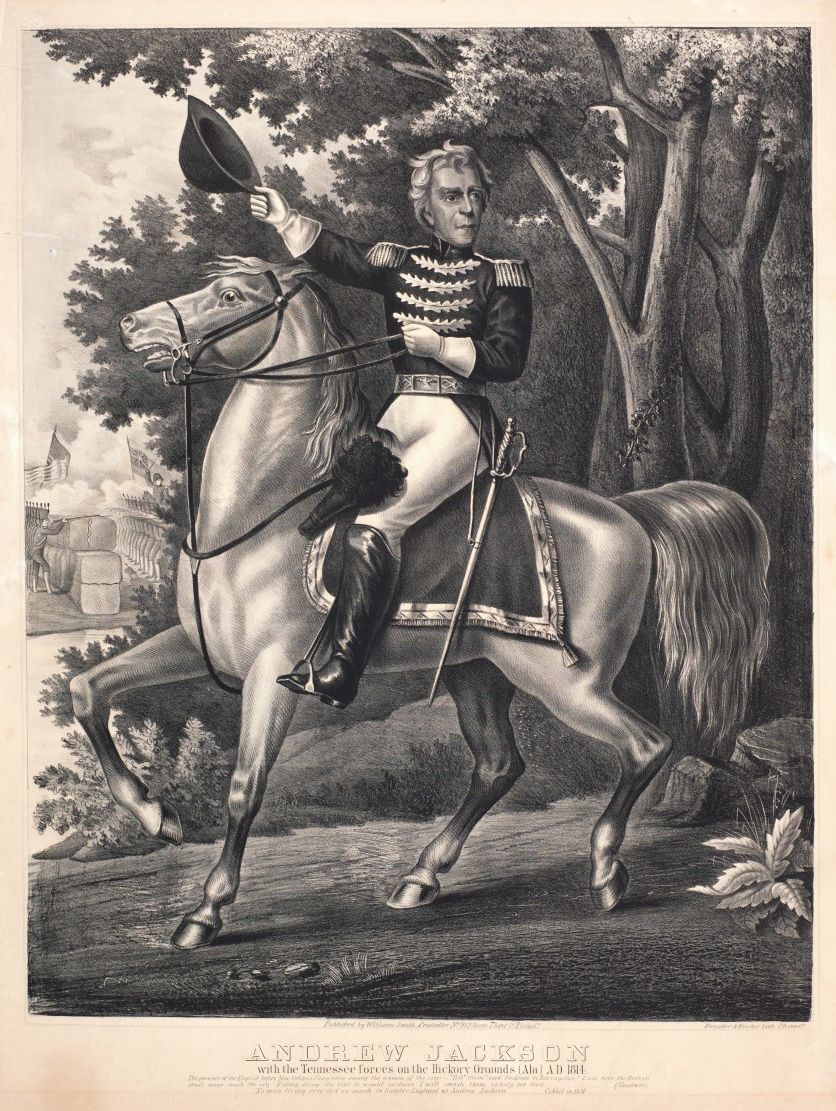

Andrew Jackson with the Tennessee forces on the Hickory Grounds [Ala] A.D. 1814

between 1834 and 1845; lithograph

by Breuker & Kessler Co., lithographer

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1968.24

Battle of New Orleans

1840; hand colored lithograph

by John Landis, artist

The Historic New Orleans Collection, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1950.25

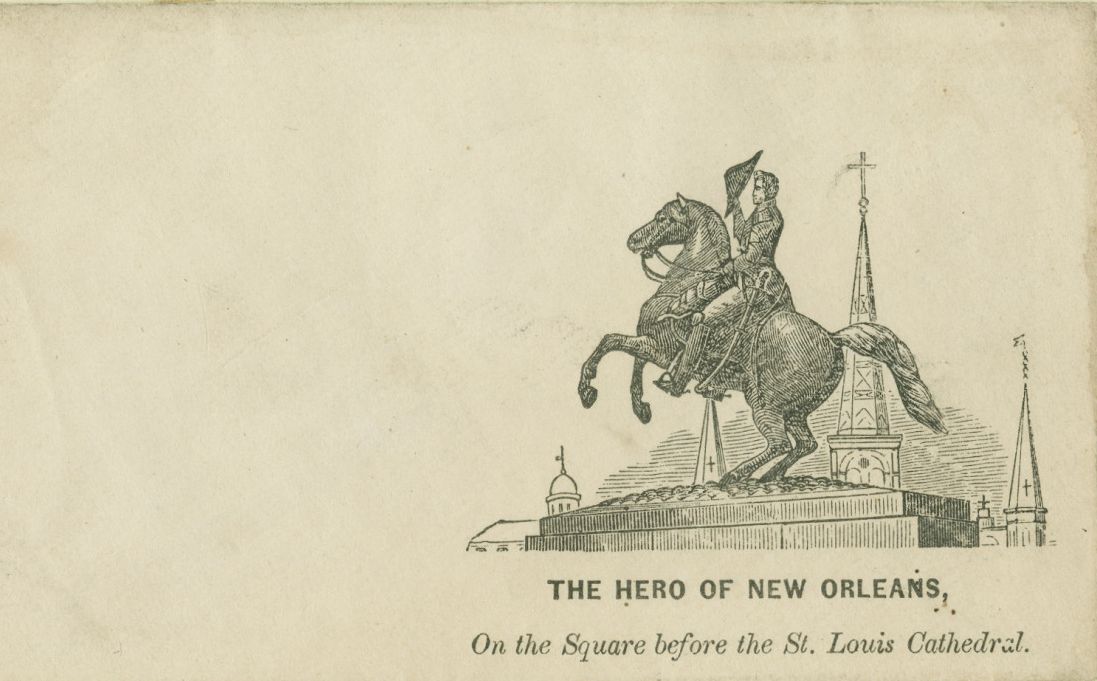

The Hero of New Orleans, On the Square before the St. Louis Cathedral

between 1850 and 1859; wood engraving

The Historic New Orleans Collection, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1956.35