In the wake of the Creek War, Jackson received a commission as a major general in the regular United States army and command of the Seventh Military District, which included Tennessee, Louisiana, the Mississippi Territory, and the land just seized from the Creek Nation. It may seem remarkable that the entire southwestern United States, including the critical port of New Orleans, was entrusted to a relatively unknown general. But the War of 1812 was not going well, and several fiascos involving Revolutionary War–era generals prompted President Madison to promote officers who got results.

General Jackson was determined to deny the British any foothold on the Gulf Coast. In early November, he and his men seized and briefly occupied Pensacola, the capital of Spanish West Florida, after hearing that British troops had been allowed the use of its harbor and forts. Soon thereafter Jackson learned that New Orleans was the objective of a large British invasion force gathering in Jamaica. Leaving some men to defend Mobile, he hastened overland to Louisiana, reaching New Orleans in early December, just as the sails of the British fleet were sighted off the coast.

In the weeks that followed, Jackson roused the diverse citizenry of New Orleans and lower Louisiana to join him in the defense against the British invaders. Public discord and Jackson’s own doubts about the loyalties of the locals persuaded him to declare martial law. Despite his misgivings, Louisianans of all colors and creeds heeded his call for aid, and local militia and regular US troops were soon augmented by volunteers from Mississippi, Tennessee, and Kentucky. This combined American force fought a number of engagements against a larger and more experienced British army under the command of Major General Sir Edward Pakenham.

The culminating battle was fought a few miles downriver from the city on the cold and rainy morning of January 8, 1815. Jackson’s strong defensive position and superior artillery overcame the coordinated attacks of British infantry regiments attacking across open ground; two British major generals, including Pakenham, were killed, and a third was wounded. More than two thousand British casualties lay scattered in front of Jackson’s line when the smoke cleared, whereas American losses were few. It was then, and is now, one of the greatest military upsets in history.

Replica of US Army major general’s coat worn by Andrew Jackson in 1814–15

2014; wool, cotton, silk thread, silk, gold thread, silver thread, wire, gold braid, pasteboard (paper), and gold-plated brass

by Steve Abolt, tailor; Timothy Pickles, embroiderer

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2014.0329

Jackson's uniform coat conformed to the 1813 regulations for general officers in the US Army: dark blue, single-breasted, with gilded buttons and gold epaulets. He likely wore a buff-colored waistcoat and buff-colored breeches or pantaloons tucked into high boots. Though regulations stipulated two silver rank stars on the epaulets, Jackson is believed to have used three stars, perhaps to signify his overall command of the Seventh Military District.

Defeat of the British Army, 12,000 strong, under the Command of Sir Edward Packenham. . .

1818; aquatint engraving with watercolor

by Jean Hyacinthe Laclotte, artist; Philibert-Louis Debucourt, engraver

The Historic New Orleans Collection, bequest of Boyd Cruise and Harold Schilke, 1989.79.135

This engraving shows the final battle that took place on the morning of January 8, 1815, and is thought to be the most accurate artistic view of the engagement. British troops were forced to attack Jackson's strong defensive position across open ground and into the teeth of superior American firepower.

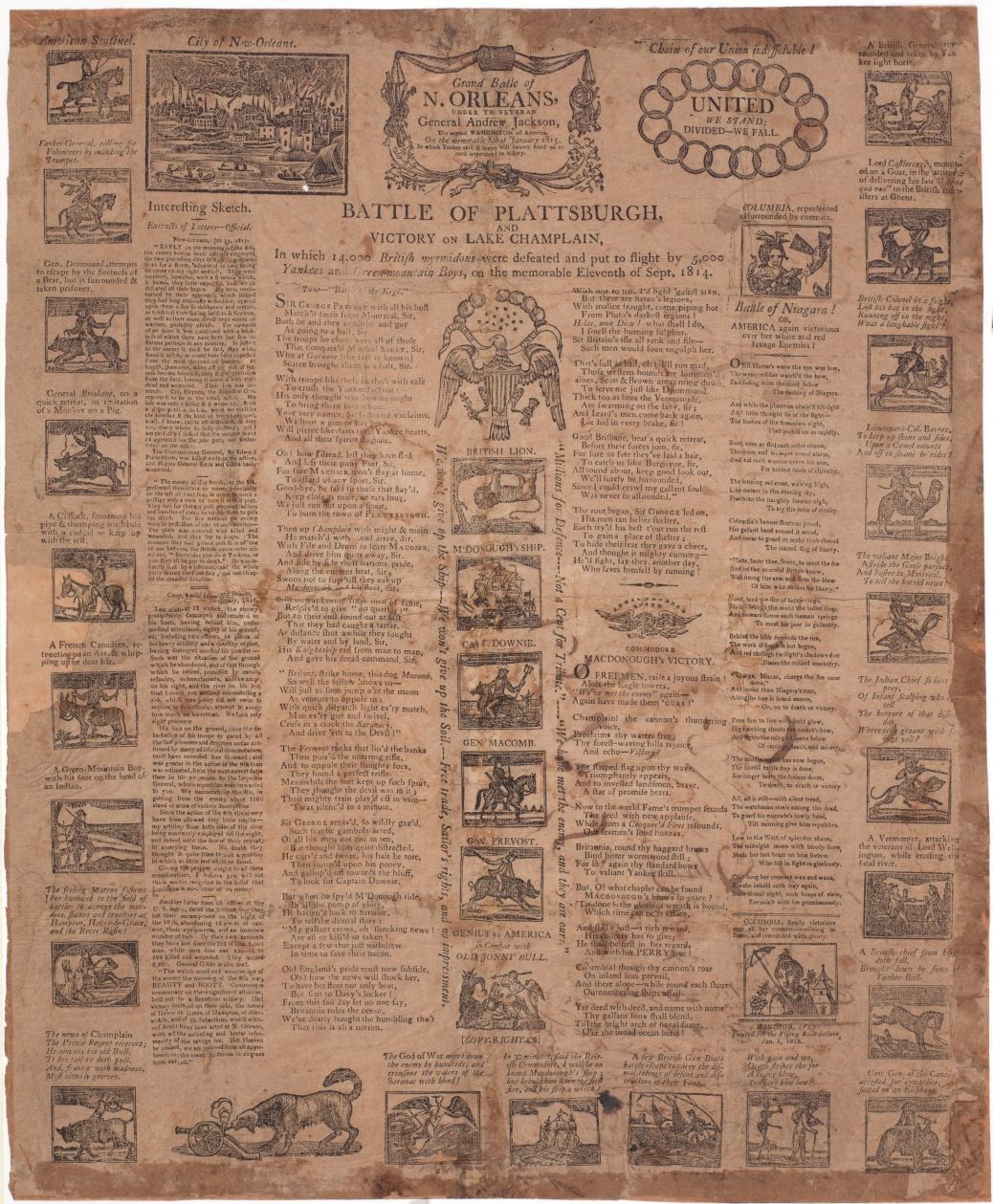

Grand Battle of N. Orleans, under the Veteran General Andrew Jackson

between 1815 and 1818; letterpress broadside with woodcut

by Flying Book-Sellers, publisher

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1953.6 i–xxxv

This New England broadside extracts official letters pertaining to the Battle of New Orleans and also highlights American victories at Plattsburgh and Lake Champlain in New York. The printer used a stock woodcut of a European city in flames as a stand-in for New Orleans, which, according to some early erroneous newspaper reports, had been sacked by the British army.

Battle of New Orleans

1856; oil on canvas

by Dennis Malone Carter, painter

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1960.22

Some artistic renderings of the battle, while dramatic, perpetuated historically inaccurate details, such as American fortifications constructed of cotton bales rather than earth and timbers and the British army's Ninety-Third Sutherland Highlanders dressed in kilts rather than the tartan trousers they actually wore on January 8, 1815.

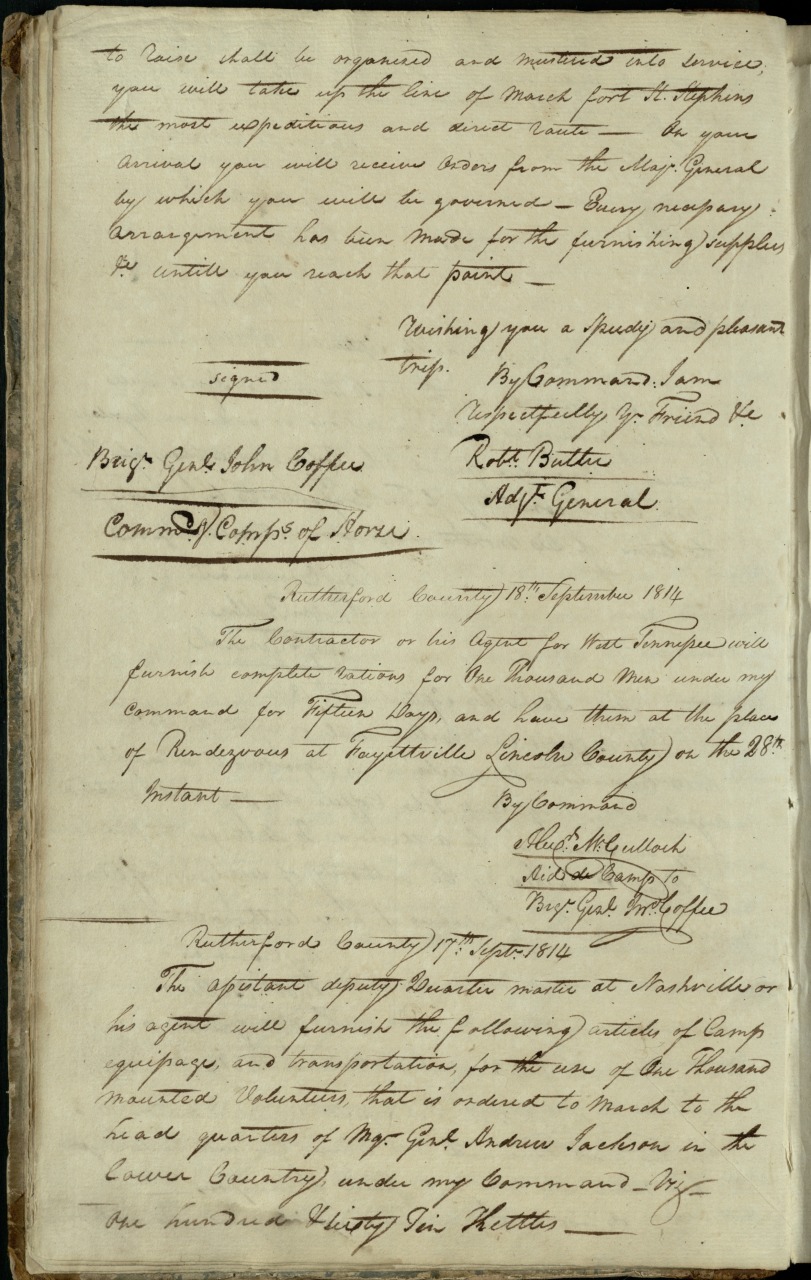

Orderly book of Brigadier General John Coffee, Tennessee Militia

September 10, 1814–March 15, 1815; manuscript volume

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2001-68-L.37

Jackson's general orders and proclamations to the citizens of New Orleans and to various militia units, including the battalions of free men of color, were recorded in the orderly book kept by Brigadier General John Coffee, a close personal friend of Jackson's.

Cannonball from the Battle of New Orleans

probably between 1812 and 1815; cast iron

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Sylvia Norman Duncan Harry MacDonald, 1994.40

Though most later descriptions of Jackson's victory highlighted the prowess of his militia riflemen and the accuracy of their the long "Kentucky rifles," the larger artillery guns spaced along American defensive positions inflicted far more casualties on advancing British troops.

M1795 Type III Harpers Ferry musket marked to the 1st Regiment of the Louisiana Militia

1813; wood, steel

by the Harper’s Ferry Armory, manufacturer

The Historic New Orleans Collection, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima fund, 2012.0296.2

This U.S. government manufactured flintlock musket is believed to have been part of a shipment of arms that arrived in New Orleans in September or October 1814. Its markings suggest it was used by a member of the 1st Regiment of Louisiana Militia at the Battle of New Orleans.

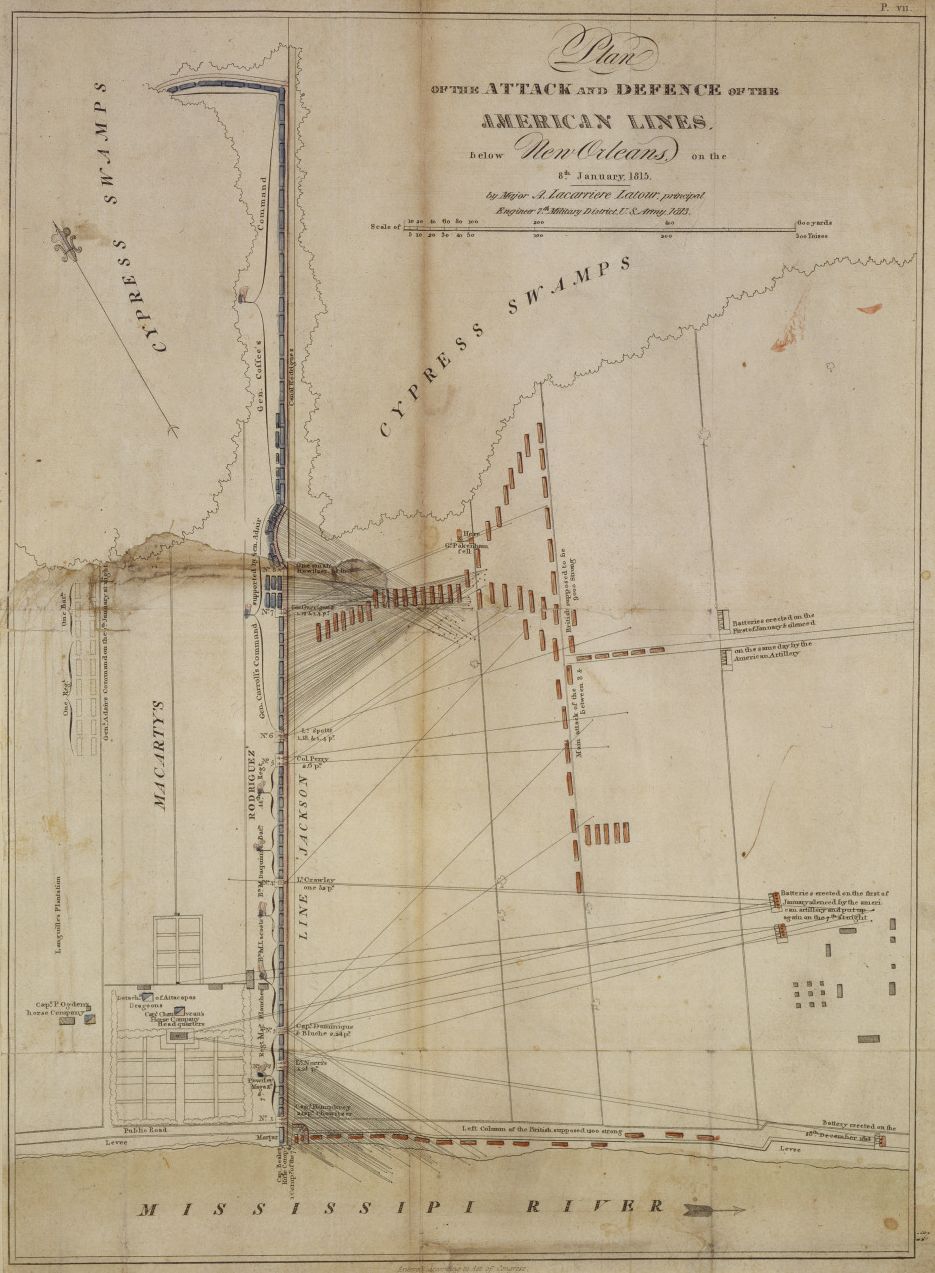

Plan Of The Attack And Defence Of The American Lines below New Orleans, on the 8th January, 1815

1816; hand-colored engraving

by Arsène Lacarrière Latour, delineator

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1979.238.4

The concentrated American fire could not be withstood, despite great discipline and fortitude on the part of the British regiments. A successful assault on the American batteries across the river did little to raise morale during the retreat.

![Battle of New Orleans and Death of Major General Packenham [sic] (1949.2 i,ii)](https://www.hnoc.org/sites/default/files/virtual-exhib/1949.2%20i%2Cii_behindglass_web.jpg)

Battle of New Orleans and Death of Major General Packenham [sic] on the 8th of January 1815

1816; hand-colored engraving

by Joseph Yeager, engraver, and William Edward West, draftsman (artist)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1949.2 i,ii