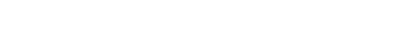

Andrew Jackson became a major general in the Tennessee Militia in February 1802, but a decade passed before he was called upon to fight. Meanwhile, tensions in the borderlands between Tennessee, the Mississippi Territory, Spanish Florida, and the Creek Nation continued to rise. Isolated attacks by Indians on white settlers were attributed in part to Spanish and British provocateurs, and Washington’s apparent indifference to the safety of western settlements frustrated local leaders. General Jackson urged his men to be ready should the Creeks “raise their Tomahawks and Scalping knives against our peaceable frontiers.” Not only would a provocation allow them to avenge “the murders and outrages committed” by the Indians, but it would also supply a pretext to seize “inviting” Creek territory and “consolidate it as part of our Union.”

A Creek attack on Fort Mims—an isolated fort on the Alabama River, approximately forty miles north of Mobile—on August 30, 1813, escalated an open war between the United States and the hostile elements of the Creek Nation, known as Red Sticks for the distinctive red war clubs they carried. As many as four hundred militia soldiers, settlers, enslaved people, and Indians were killed. When news of the Fort Mims massacre reached Nashville, General Jackson was recovering from a gunshot wound suffered in a duel. Legislator Enoch Parsons expressed regret that Jackson would be unable to take the field with mobilized Tennessee troops, but Jackson is said to have responded, “The Devil in Hell, he is not!” As his men mustered for duty, Jackson was there in the saddle to lead them, his arm in a sling.

Over the next several months, Jackson carried the fight into the heart of Creek territory, and though he lacked formal training as an officer, his tactical instincts and stubborn refusal to fail sustained a successful offensive campaign. After victories at Tallushatchee and Talladega, General Jackson struggled in the winter months of 1814 to overcome logistical hurdles, such as expiring militia enlistments, as well as costly skirmishes at Emuckfaw and Enitochopco Creek, before reinforcements enabled him to renew the campaign. The decisive battle against the Red Sticks was fought at Tohopeka (Horseshoe Bend) on the Tallapoosa River in what is now central Alabama. An estimated one thousand warriors held a fortified position, but Jackson’s superior numbers and firepower encircled and eventually overwhelmed the Creeks. “It was dark before we finished killing them,” the general later wrote.

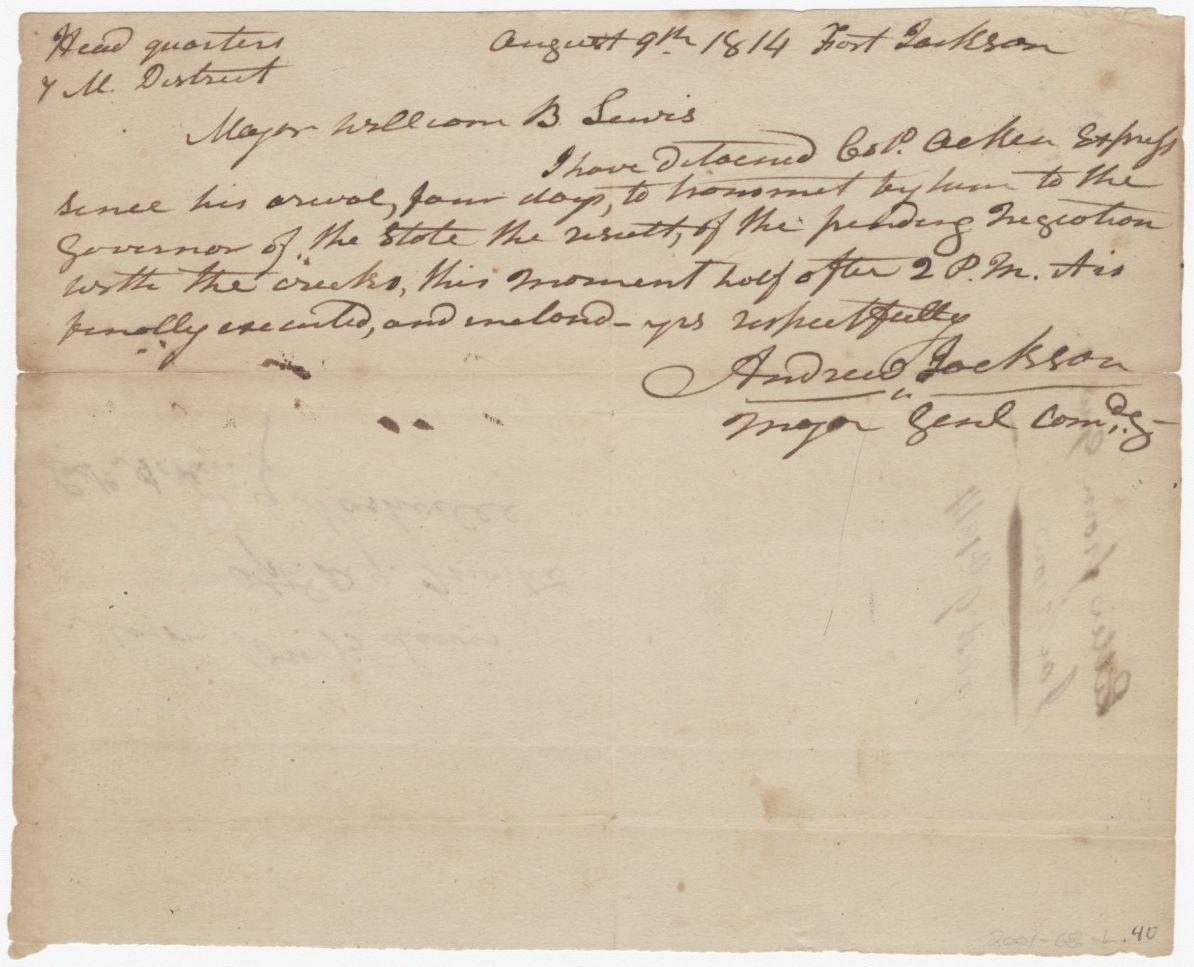

After the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, Jackson moved on to the confluence of the Tallapoosa and Coosa Rivers, where an American fort was being constructed on the former site of Fort Toulouse, built by the French in the eighteenth century. Jackson was astonished when the fugitive Red Stick leader William Weatherford, also known as Lamochattee (Red Eagle), entered the American camp alone and unarmed, seeking peace from his victorious enemy. Weatherford’s brave gesture and the friendship of Jackson’s faithful Creek allies little availed the Creek Nation when it came to the treaty negotiations that took place at the fort, which would later bear Jackson’s name, the following August. There, Jackson demanded and received the cession of more than half of the Creeks’ ancestral lands, or about three-fifths of what would become the state of Alabama. By this time, Jackson’s Indian friends and foes had begun to refer to him by a new nickname: Sharp Knife. With the Treaty of Fort Jackson, he slashed an opening for American expansion all the way to Spanish Florida, where British officers were rumored to be plotting a new offensive on the southern coast.

Address “to the brave and patriotic volunteers of Tennessee . . .”

1813; letterpress handbill

by Andrew Jackson, author

The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 200, 55-40-L

The British sought to exploit their historical ties with western tribes by arming Creek and Seminole warriors in West Florida. The plan to raise an Indian army might have succeeded were it not for the intervention of a determined American general named Andrew Jackson.

The United States’ Gazette

November 27, 1813; newspaper

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2008.0226.3General Jackson's published letter to Tennessee's governor, William Blount, declares that his men "retaliated for the destruction of Fort Mims" and reports the victory of Tennessee troops over the hostile Creeks at Tallusatchee, in present-day Alabama.

The Georgia Militia under Gen. Floyd, Attacking the Creek Indians at Autossee . . .

1825; hand-colored engraving

by J. W. B., draftsman (artist) and engraver

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2011.0181

Tennessee and Georgia militia troops penetrated deep into Creek territory. This engraving shows the Upper Creek, or Red Stick, warriors opposing Georgia militia troops at the Creek town of Atasi (Auttose) on the Tallapoosa River, in present-day Macon County, Alabama.

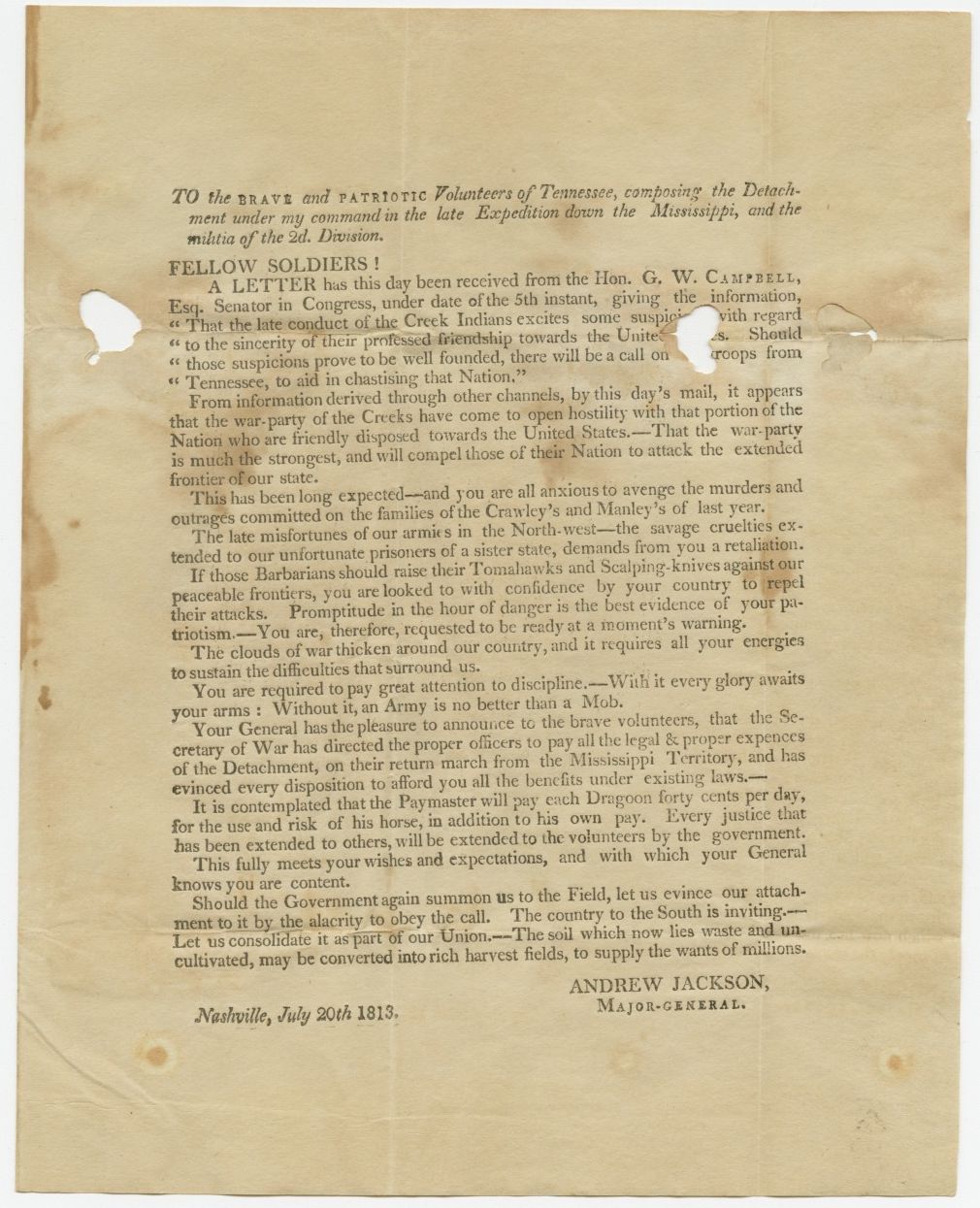

Note regarding the signing of the Treaty of Fort Jackson

August 9, 1814; manuscript document

by Andrew Jackson, author

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2001-68-L.40

Moments after a peace treaty with the Creeks was signed, General Jackson sent express news of the event to Governor William Blount in Nashville. The treaty added more than half of the Creek Nation's ancestral lands to the United States. The Creek and Cherokee chiefs who were compelled to sign the treaty were shocked and dismayed by its harsh terms, especially because some of them had fought at Jackson's side as allies during the Creek War.

Circular letter regarding the Treaty of Fort Jackson

1814; letterpress document

by Andrew Jackson, Benjamin Hawkins, and Return J. Meigs, signers

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2001-68-L.41

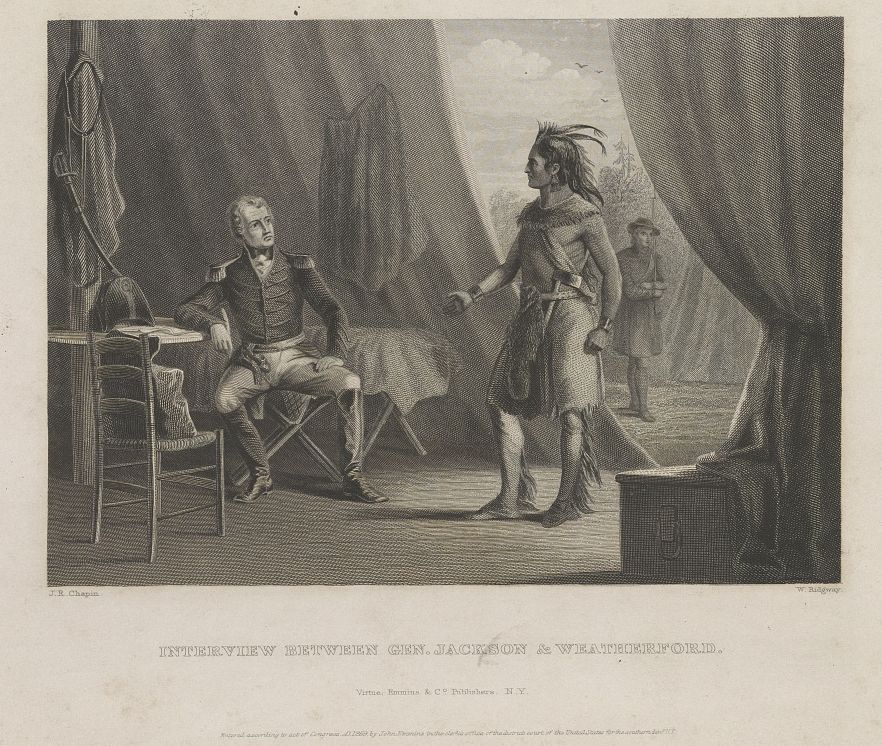

Interview between Andrew Jackson and William Weatherford

1859; steel engraving

by John R. Chapin, artist; W. Ridgeway, engraver

courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, PRES FILE—Jackson, Andrew, 1767–1845—Military life

After the annihilation of most of his remaining warriors at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in March 1814, the Red Stick leader William Weatherford, also known as Lamochattee (Red Eagle), entered General Jackson's camp alone and unarmed to seek peace from his victorious enemy.

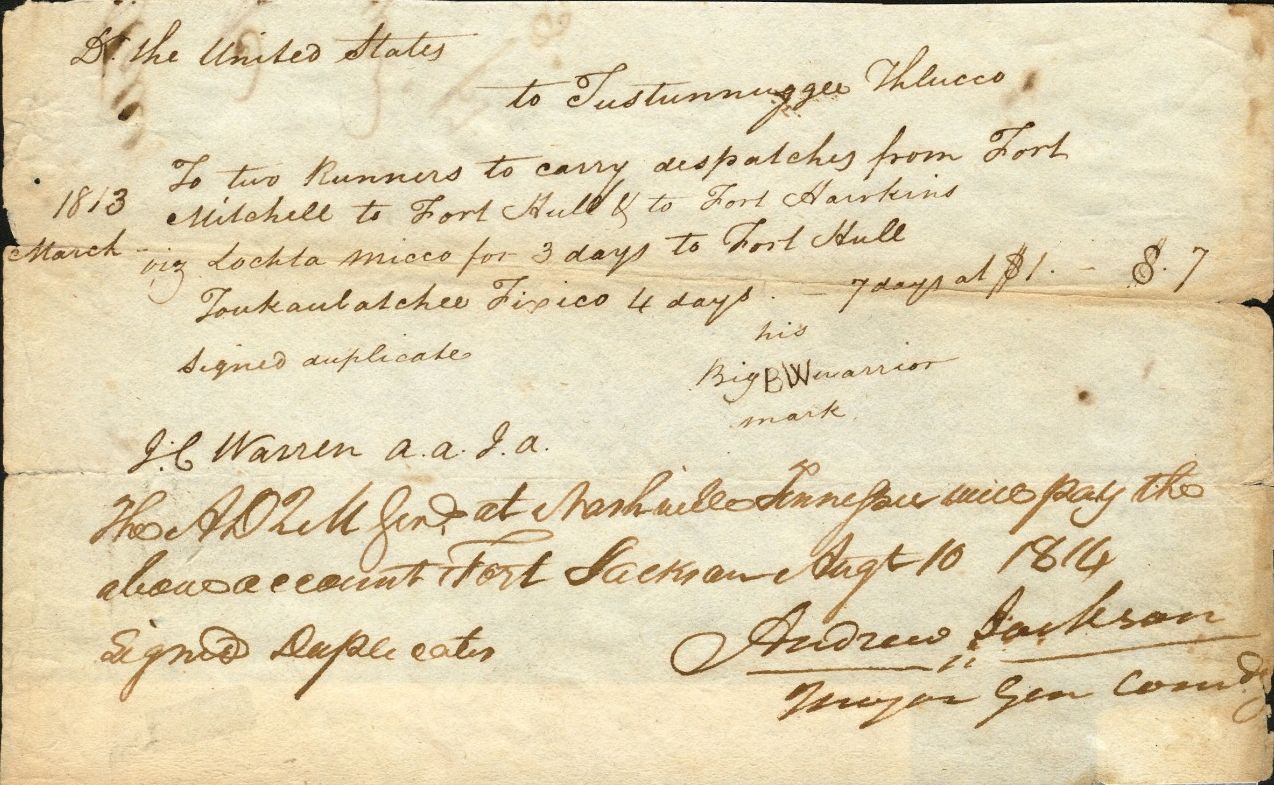

Andrew Jackson payment order for Creek chieftain Big Warrior

August 10, 1814; manuscript document

by Andrew Jackson, signer

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2006.0313.28

Mississippi Territory

1814; engraving

by Mathew Carey, publisher

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1998.53.23