General Jackson's arrival in New Orleans in 1814 was preceded by weeks of urgent correspondence from Governor William C. C. Claiborne questioning the loyalty of Louisianans to the United States. After having read a proclamation to the "Natives of Louisiana" from a British officer and seeing firsthand the panic and disorder preceding the British landing, Jackson declared martial law on December 16, 1814, suspending the free movement of citizens and placing everyone under his military authority. It was an unprecedented move for an American general, one that would have lasting ramifications for Jackson and the country at large.

Soon after the decisive defeat of the British army at Chalmette and the subsequent departure of its surviving troops, locals implored Jackson to heed reports of a peace treaty and lift the military curfews and restrictions that had become a hardship. Jackson would not do so while the British army remained in the Gulf region and without official word from Washington. When a newspaper editorial criticized the general's heavy-handedness with the local French population, Jackson had the writer, a state senator, arrested for inciting mutiny. A federal judge who attempted to intervene was also arrested and subsequently banished from Jackson's military jurisdiction. Official news of the war's end reached Jackson’s headquarters in mid-March, and he immediately lifted martial law. Within days he received a summons from the judge he had arrested, Dominick A. Hall of the District Court of Louisiana. Hall ultimately fined the general $1,000 for contempt of court. Jackson quietly paid the hefty fine before his departure, but he also obtained statements from fellow officers in support of his use of martial law during the crisis.

In the elections of 1824 and 1828, Jackson’s political opponents lambasted his trampling of the Constitution, but Jackson never apologized for his decision, stating that he would "under similar circumstances not refrain from a course equally bold." After Jackson's retirement from the presidency, his friends mounted a campaign to have the 1815 fine refunded to the general, with interest. A heated national debate in the early 1840s led to resolutions supporting Jackson in various state legislatures. Early in 1844, President John Tyler signed the joint congressional resolution refunding the fine with interest. Even so, because of its constitutional implications, the episode remains controversial to this day. As the historian James Parton observed, "the maintaining of martial law in New Orleans two months too long, we may condemn, and, I think, should condemn; yet most of the citizens of the United States will concur in the wish, that when next a [foreign] army lands upon American soil, there may be a Jackson to meet them at the landing-place."

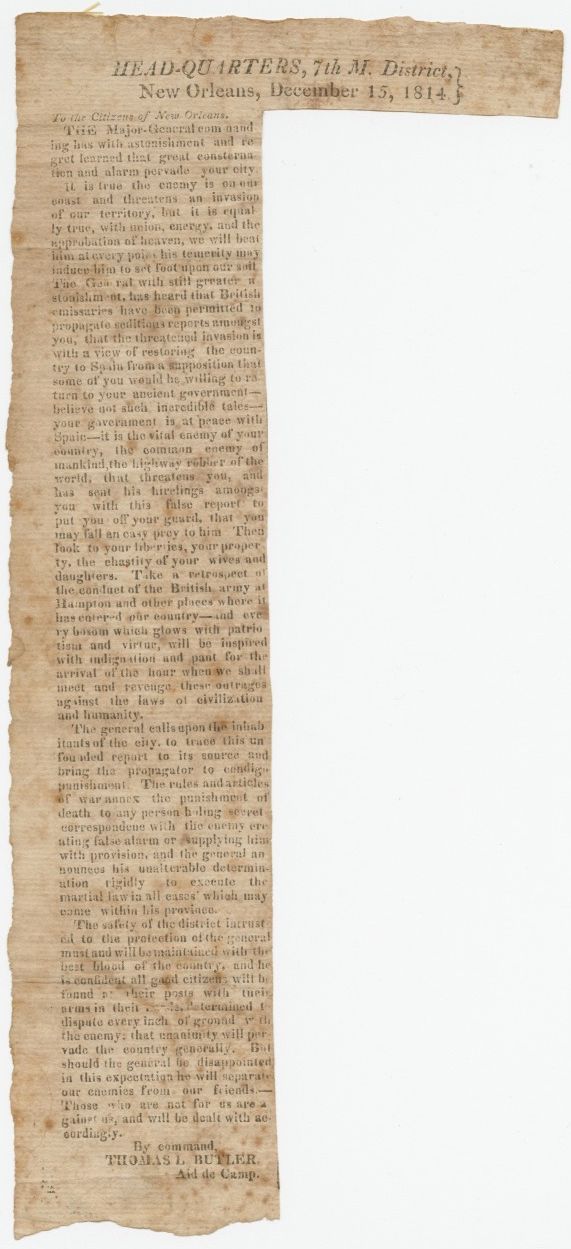

Notice from Seventh Military District Headquarters "to the Citizens of New Orleans"

December 15, 1814; letterpress clipping

by Thomas L. Butler, signer

The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 208, 49-12-L

General Jackson published an address to calm public panic following reports of a British victory against American gunboats on Lake Borgne. On the following day, December 16, 1814, he declared martial law in the city, suspending the free speech and movement of its citizens and making everyone subject to his military authority.

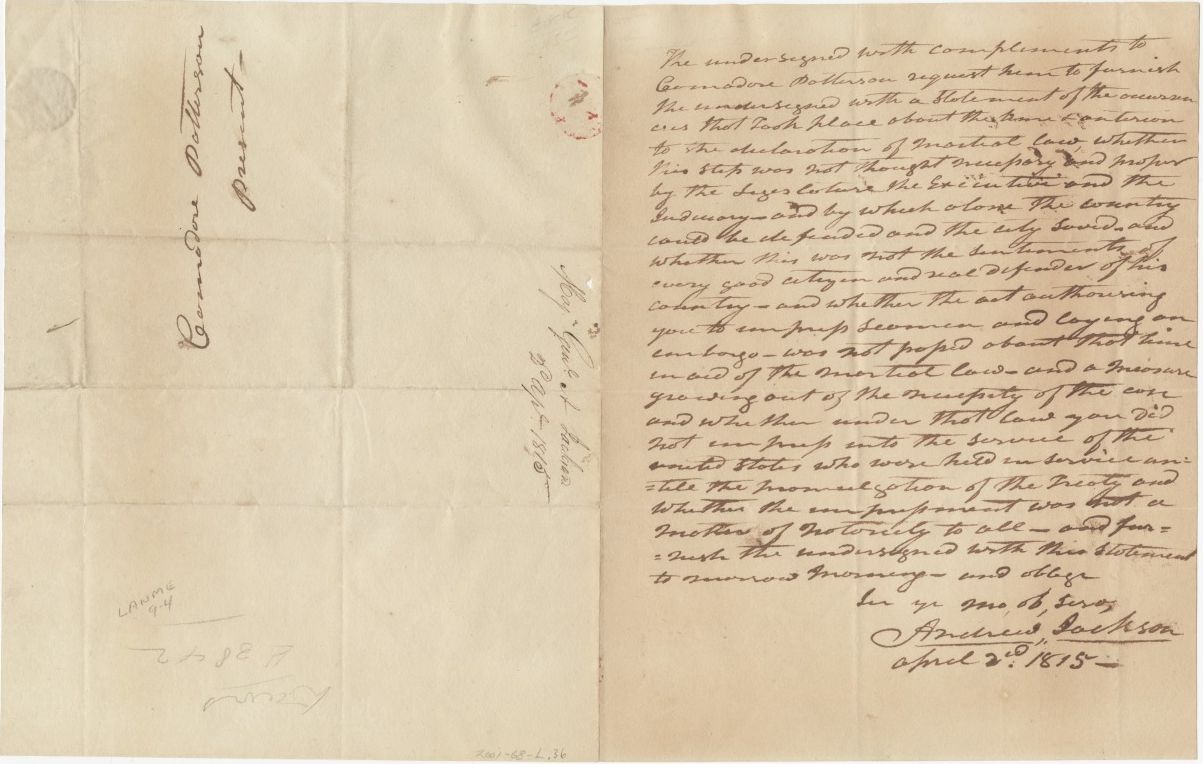

Note from Andrew Jackson to Daniel T. Patterson concerning martial law in New Orleans

April 2, 1815; manuscript letter

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2001-68-L.36

Around the time of his departure from New Orleans, General Jackson requested a statement in support of his use of martial law from the ranking US naval officer in New Orleans, Captain Daniel Todd Patterson (1786–1839).

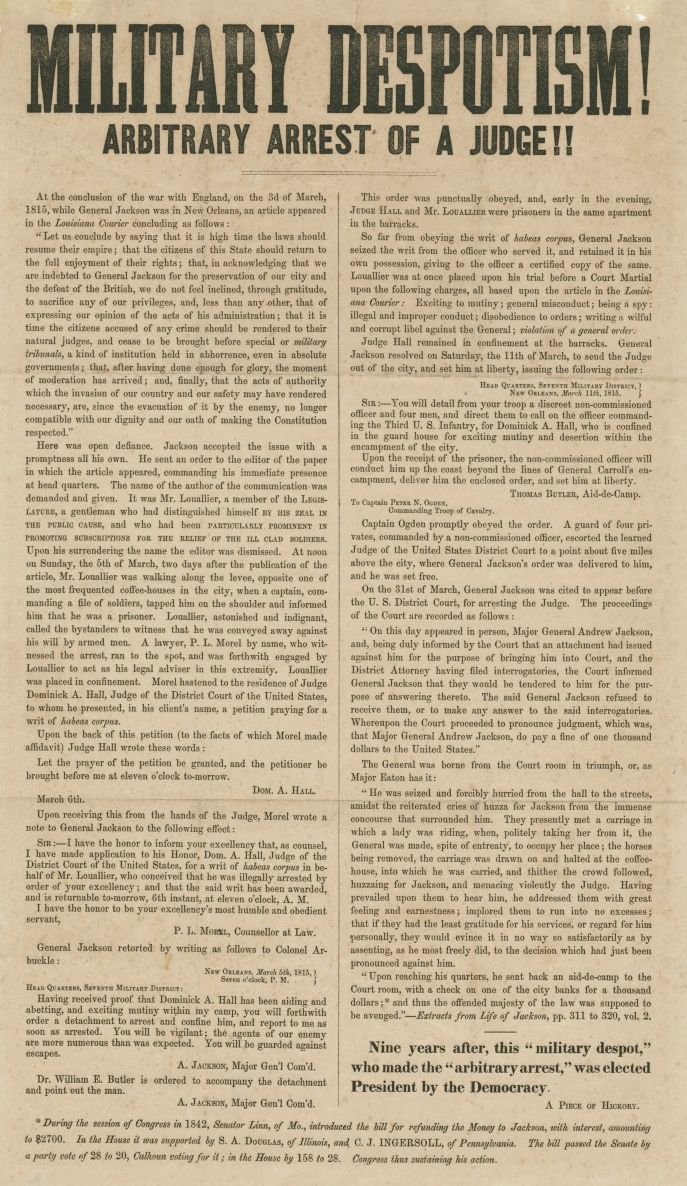

Military Despotism! Arbitrary Arrest of a Judge!!

between 1842 and 1845; letterpress broadside

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 86-2234-RL

This broadside from an unknown publisher offers a scathing account of the March 1815 arrest of Louis Louaillier, a member of the Louisiana legislature who had written a newspaper editorial critical of General Jackson's policy of banning French volunteers from New Orleans after they had helped to defend the city, and the subsequent arrest of US District Court Judge Dominick A. Hall, who had sought Louaillier's release. Louaillier's name is misspelled "Louallier" throughout.

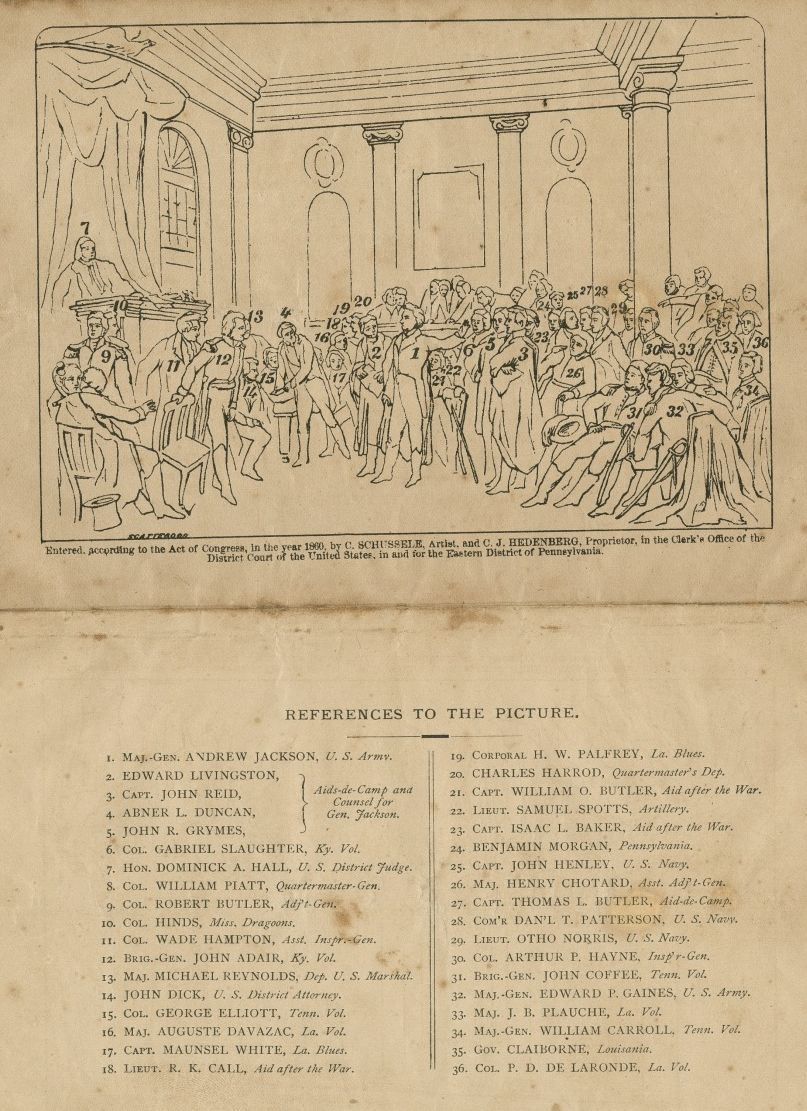

Explanation of the Picture of Andrew Jackson, before Judge Hall at New Orleans, 1815, Sustaining the Laws of His Country, as He Had Defended Her Liberties in the Field

by Richard Keith Hall, C. J. Hedenberg, and Christian Schussele, authors

New York: Martin B. Brown, [1860?]

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 93-357-RL

C. J. Hedenberg, a well-to-do Philadelphia shoe merchant and Jackson supporter, commissioned artist Christian Schussele (1824–1879) to depict Old Hickory's trial before Judge Dominick Hall in 1815. Many of Jackson's military and civilian allies appear in Schussele's rendering and are identified in this pamphlet published soon after the painting's completion in 1859. The original painting is now in the collection of the Gilcrease Museum.

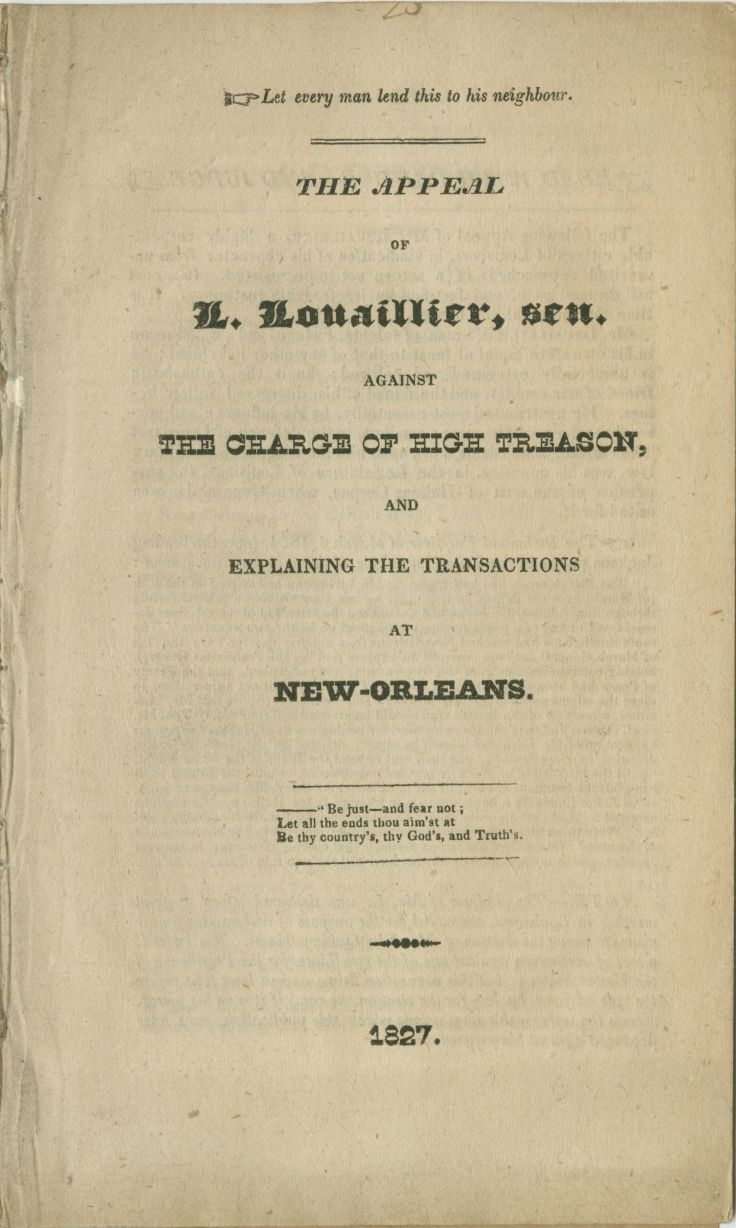

The Appeal of L. Louaillier, Sen., against the Charge of High Treason: and Explaining the Transactions at New-Orleans

by Louis Louaillier, author

New Orleans, 1827

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 76-839-RL

Years after his arrest by Andrew Jackson and as the former general campaigned for the presidency, Louis Louaillier presented a written defense of his own conduct in 1815 and an attack on Jackson's character.

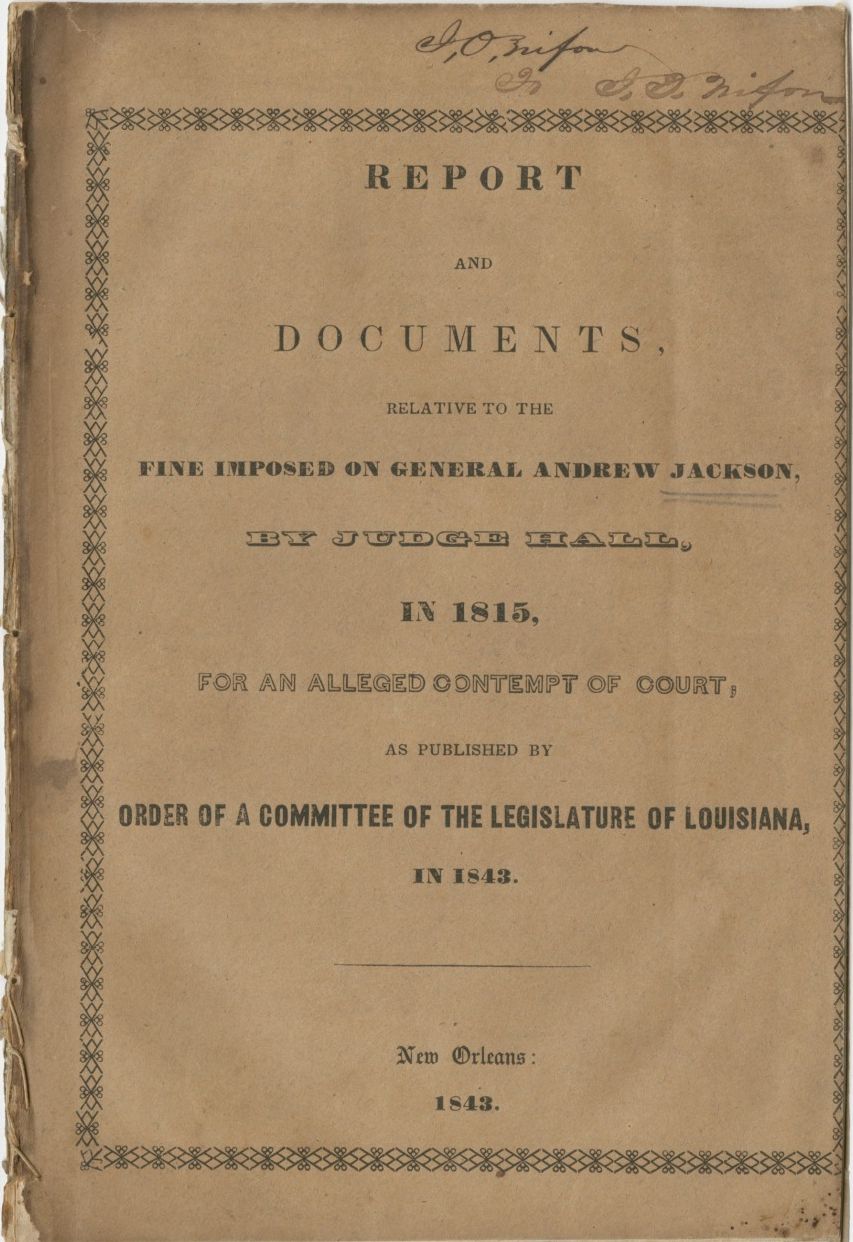

Report of the Committee of the Senate in Relation to the Fine Imposed on Gen. Jackson: Together with the Documents Accompanying the Same

New Orleans, 1843

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2014.0089

Official government reports concerning the circumstances of General Jackson's trial and fine in 1815 were printed in Washington and elsewhere in the early 1840s to inform the spirited public debate over the question of a possible refund.

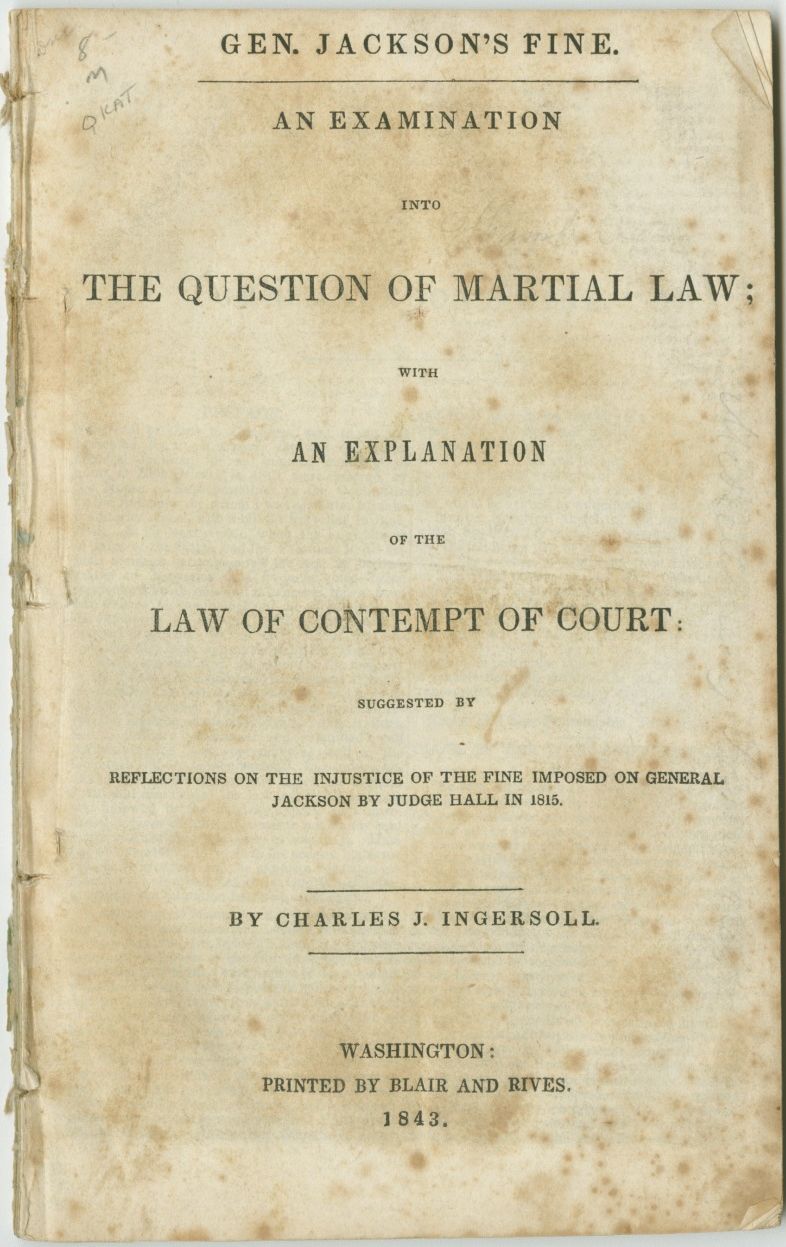

Gen. Jackson’s Fine: an Examination into the Question of Martial Law . . . Suggested by Reflections on the Injustice of the Fine Imposed on General Jackson by Judge Hall in 1815

by Charles J. Ingersoll, author

Washington, DC: printed by Blair and Rives, 1843

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2006.0421.54

Charles Jared Ingersoll (1782–1862), an attorney and Democratic congressman from Pennsylvania, published a history of the War of 1812 in four volumes (1845–52). Several of Ingersoll's speeches on the conflict and its origins had appeared in pamphlets and newspapers during the war.

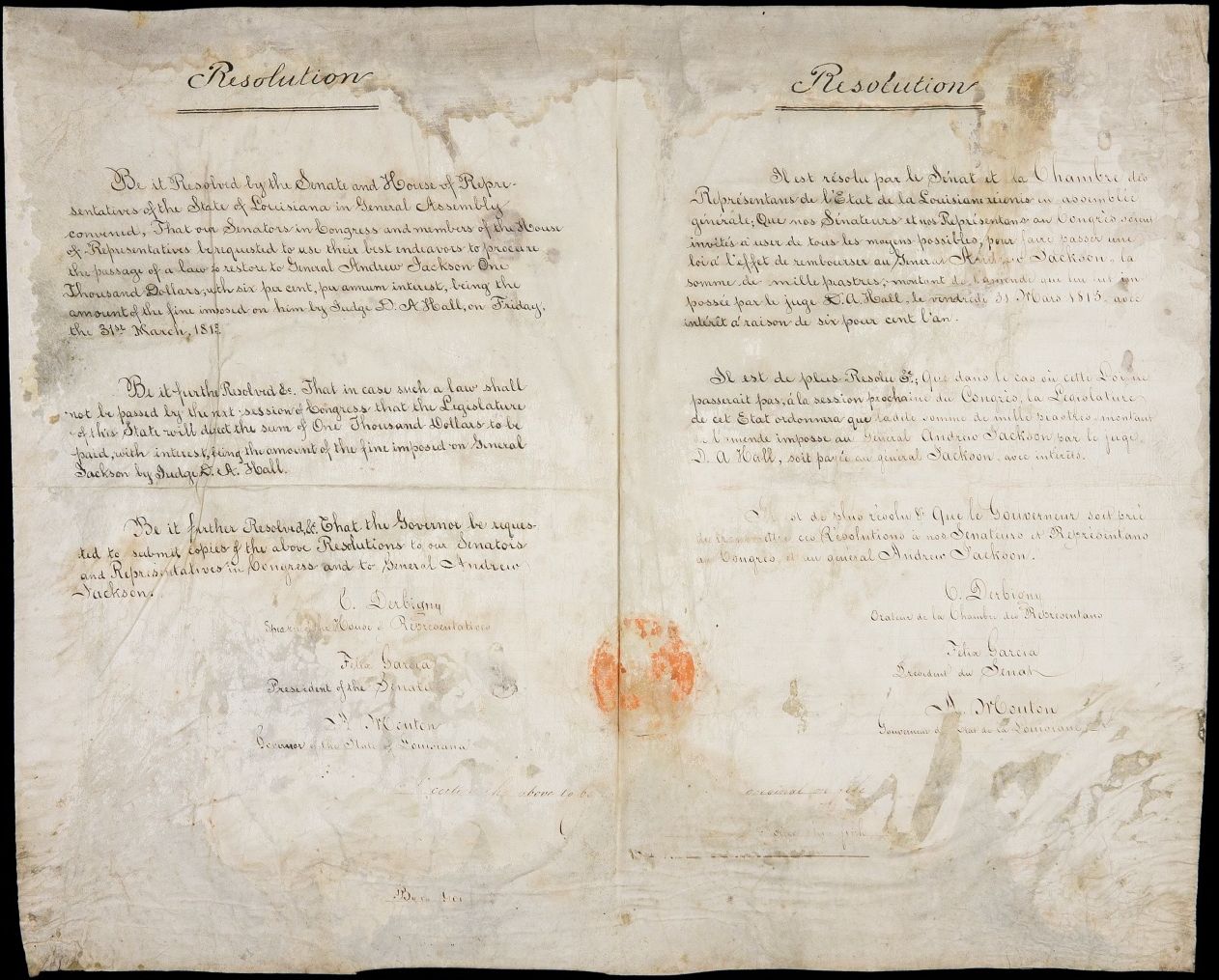

Joint resolution of the Louisiana Senate and House of Representatives regarding Andrew Jackson’s fine

1843–44; manuscript document

The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 594, 2005.0226.1

Louisiana's bilingual legislative resolution "to procure the passage of a [federal] law to restore to General Andrew Jackson One Thousand Dollars . . ." was signed on behalf of Charles Derbigny, Speaker of the House of Representatives, Felix Garcia, president of the Senate, and Alexandre Mouton, governor of Louisiana.

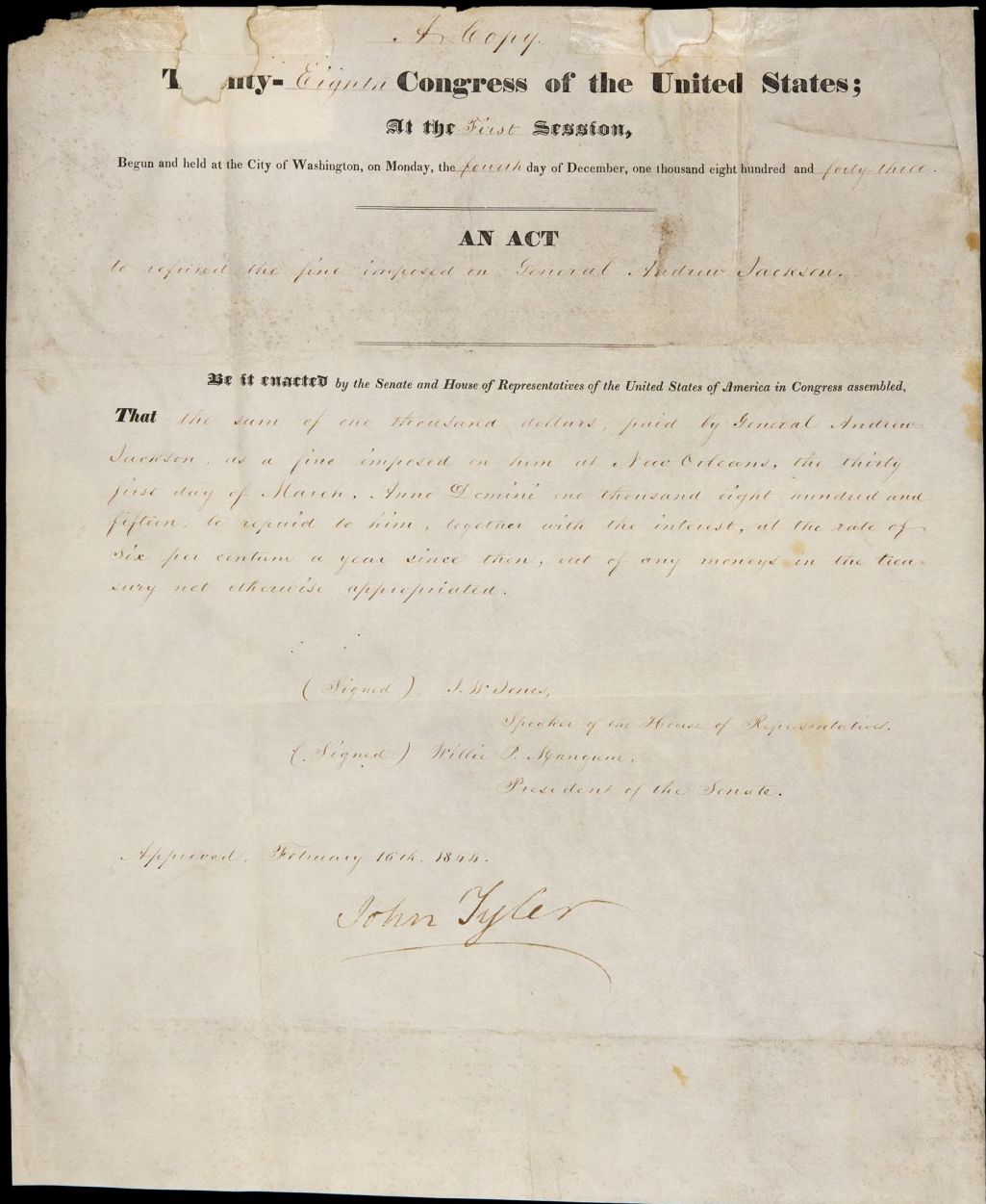

Act by the Twenty-Eighth Congress of the United States refunding Andrew Jackson’s fine, signed by President John Tyler

1843–44; printed and manuscript document

The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 594, 2005.0226.2

The national resolution to restore Jackson's fine was taken up in December 1843 and approved the following February. The final document was signed on behalf of the Speaker of the House and the president of the Senate and signed by President Tyler.