Banking in the Antebellum South

Louisiana’s first banks—the Bank of Louisiana and a branch of the First Bank of the United States—opened on Royal Street in 1805. Each circulated its own notes, extended credit, accepted deposits, exchanged money, and engaged in a variety of other financial activities suited to a booming port town. By 1830 New Orleans boasted five banks, and just four years later that number had ballooned to twelve. New state-chartered banks—such as the Bank of Orleans, Citizens’ Bank, Mechanics and Traders Bank, Union Bank, and Consolidated Association of Planters—competed to underwrite expanding markets in land, cotton, sugar, and enslaved people. Growth in Louisiana’s banking sector was in line with larger patterns in the US economy, where confidence in emerging markets had led to a 36 percent increase in the country’s gross domestic product between 1830 and 1836, the year the financial sector began to crumble.

The beauty of banknotes was that as long as the public had confidence in their value, banks could print and circulate more paper currency than the amount of specie kept in their vaults. But when trust in that system failed, as it did when transatlantic credit markets contracted in the late 1830s, so too did banks, leaving businesses and individuals holding worthless paper notes. During the Panic of 1837, the name commonly applied to one of the worst financial crises in US history, banks suspended specie payments, and creditors ranging from state governments to individual property owners defaulted on their debts. The Panic of 1837 was not the only economic crash of the antebellum period. Markets followed a boom-and-bust pattern throughout the nineteenth century, with much of the credit available in the South prior to 1865 tied up in cotton and the enslaved laborers who picked it.

![[Second] Bank of the United States five-dollar note (1989.59.6)](https://www.hnoc.org/sites/default/files/virtual-exhib/1989.59.6_recto_web.jpg)

[Second] Bank of the United States five-dollar note

May 11, 1829; engraving

by Fairman, Draper, Underwood, and Company, printer (Philadelphia)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1989.59.6

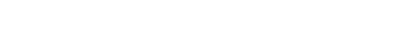

Union Bank of Louisiana one-hundred-dollar note

November 7, 1856; engraving

by Toppan, Carpenter, and Company, printer (Philadelphia)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of the Randy K. Haynie Collection, 2016.0020

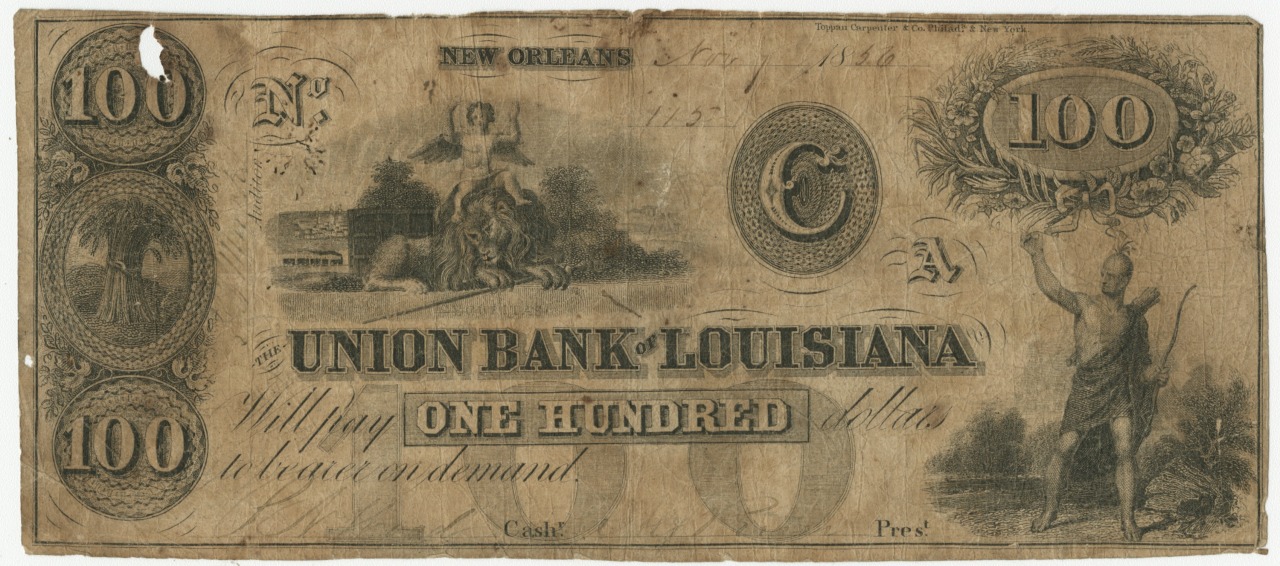

Bill of exchange, New Orleans

December 15, 1854; engraving

by Rawdon, Wright, Hatch, and Edson, printer (New Orleans)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Samuel Wilson Jr., 1981.368.3While banknotes facilitated trade and payment within the boundaries of the United States, bills of exchange were the preferred financial instrument of merchants engaged in international commerce. Backed by pre-existing lines of credit, bills of exchange functioned much like modern-day bank checks, with payment made to an assigned recipient on presentation at the issuing party’s financial institution. Notes like this one, known as “sixty-day sight bills” (so named for the length of time a bank sat on funds between presentation and payout), were frequently employed in the transatlantic cotton trade.

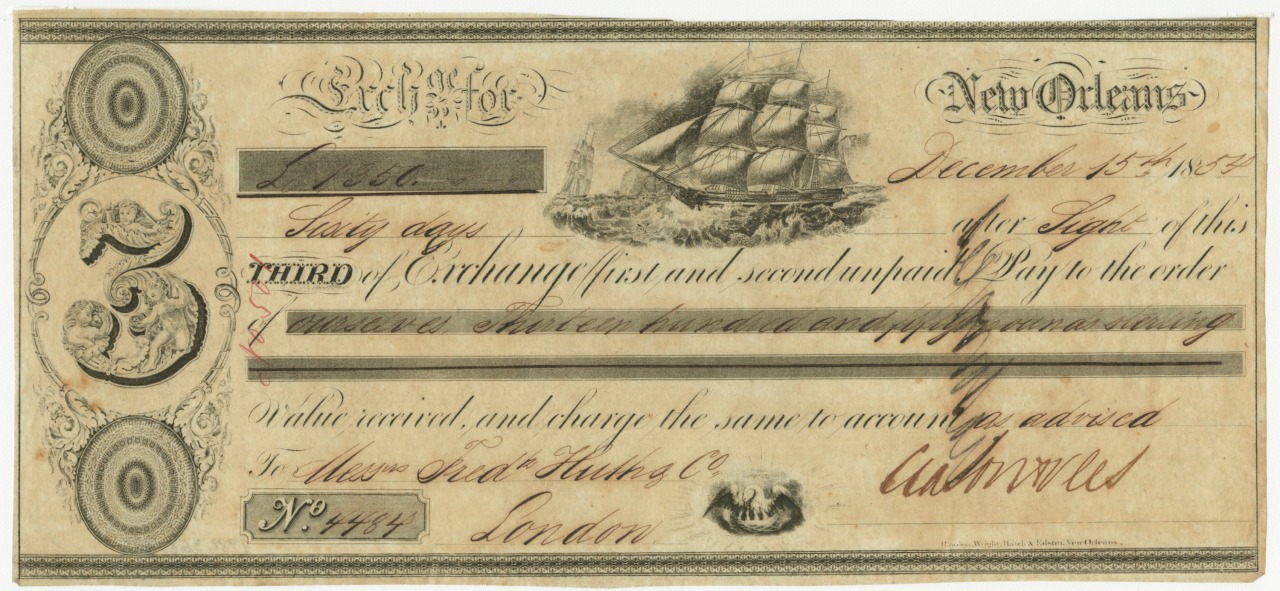

Mechanics and Traders Bank two-dollar note

1840s; engraving

by American Bank Note Company, printer (New York)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1989.59.13

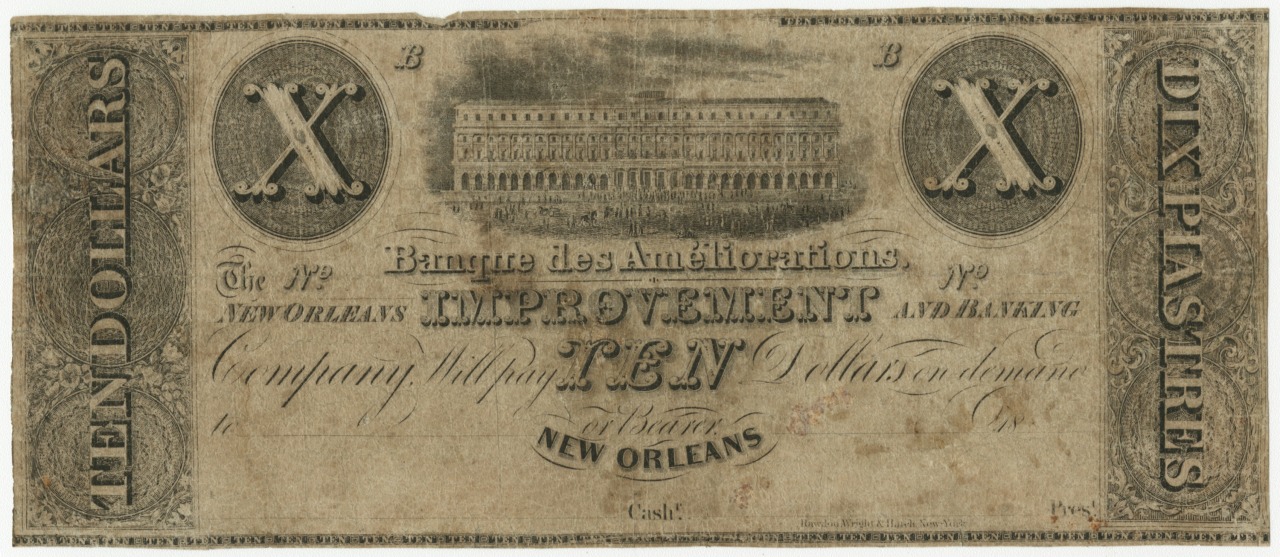

Banque des Ameliorations, New Orleans Improvement and Banking Company, ten-dollar note

between 1832 and 1847; engraving

by Rawdon, Wright, and Hatch, printer (New York)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1989.59.11

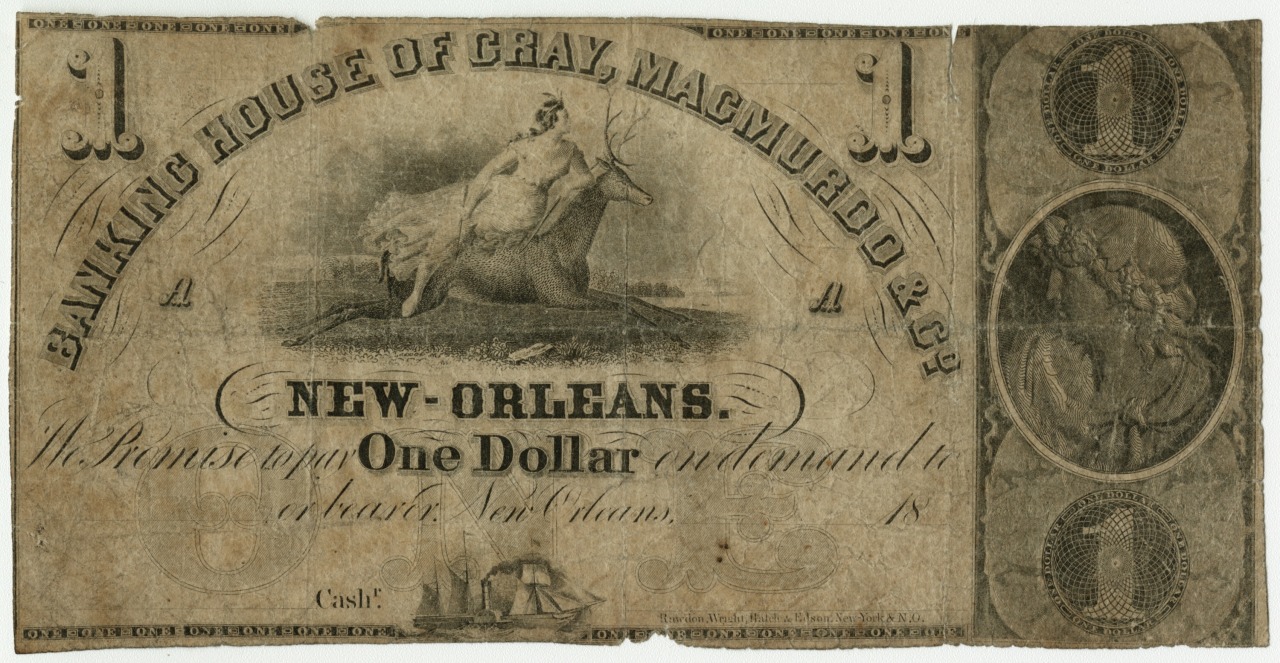

Banking House of Gray, Macmurdo and Company one-dollar note

1840s; engraving

by Rawdon, Wright, Hatch, and Edson, printer (New York or New Orleans)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1989.59.7

Exchange and Banking Company of New Orleans five-dollar note

July 25, 1840; engraving

by Underwood, Bald, Spencer, and Hufty, printer; Danforth, Underwood, and Company, printer (Philadelphia or New York)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1989.59.10

City Bank, New Orleans, one-hundred-dollar note

November 17, 1849; engraving

by Rawdon, Wright, Hatch, and Edson, printer (New Orleans)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1989.59.9

Bank of New Orleans twenty-dollar note

1850; engraving

by Rawdon, Wright, Hatch, and Edson, printer (New Orleans)

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1989.95.5