Dancing in the street in New Orleans means something completely different than in 99.9% of your other major American cities. Here, most likely, it will be related to a second line with a brass band. You either have a body or you have cut the body loose. Or it could also just be a Sunday and a club is celebrating its anniversary for the next four hours by dancing in the street. There are no barricades. It's a participatory event. You can watch it, but you can also get in it, and walk, sing, cry, and dance along. You can go as far as you want or go the whole route.

One time, my friend Glennon Bazile was in New York and somebody died in New Orleans, but he couldn't get home. He got himself a shopping cart, a boombox, and an umbrella. He said he started at 110 and Lennox and paraded through Harlem. People were looking at him like, “Where’d this motherfucker come from?!” He’s an alien, but he was rolling it, listening to some Olympia Brass Band.

Growing up, I lived in the same house as my uncle Roy “Sundown” Johnson. They lived in the front, we lived in the back. One Sunday morning when I was around ten, I saw him getting dressed. I knew what was up when I saw him with feathers. He left out the house, and I left right behind him, following him all the way up to a club called Holly’s on Orleans and North Villere. I stayed on the other side of the street so he wouldn’t notice me. He was a member of the Sixth Ward Diamonds. I followed their parade. I think I caught a good ass whipping that day because I was gone all day. I credit watching those men for teaching me how a formation of a division should be run on the street. They didn’t use a rope because everybody had a partner—a buddy—who they danced with and kept the crowd in line.

The first second line I paraded in was with Tamborine & Fan’s Bucket Men. The founders, Jerome Smith and Rudy Lombard, told us stories about the Longshoremen’s Labor Day parade.

I never got to witness it, but they said the longshoremen wore their work uniform with the bib overalls, and they’d bring the tool they worked with. There'd be hundreds of them. In honor of them, the Bucketmen paraded in overalls, too. My youngest brother, Willie Malo, left to go to Tuskegee, but I made a point of keeping him in the First Division of the Bucketmen with our other brother, Glenn, and me. He came down from school and brought some of his friends with him. They’d never saw nothing like that in their lives.

When the jazz musician, Danny Barker, came back home from New York City, he got involved with Tamborine & Fan, too, and supported a lot of other musicians with the youth band he founded, the Fairview Baptist Church Band.

Those musicians, like Gregg Stafford, grew up, and began to form their own bands. Danny started doing more writing, working at the Jazz Museum, and playing other sit-down gigs. When he died, we all got together to make sure he had a jazz funeral he would have been proud to see—the music was so powerful that guys said, “Listen, we need to do this again.”

I said, “Yeah, but not with a body.” That's how Black Men of Labor came about—we were trying to pay homage to him. I met with Gregg and Benny Jones, Sr., the leader of the Treme Brass Band, and we created a parade to put the band back on the street in black and white. Our first parade was on Labor Day of 1994. In tribute to the Longshoremen’s and Bucketmen’s parades, the first year we wore blue denim and the second year we had on the brown overalls. The third year we wore a suit for the first time with shoes that were a throwback to the 1960s.

Different music and different tempos create different responses. In a dirge, it’s much more dignified and uniform when everybody decides to start off on the same foot because then it’s in rhythm with the music. The tempo of the music slows up so you can’t have everybody just doing anything. There’s beauty in the discipline. As our organization was founded around a traditional jazz funeral, when someone in our community passes away—without overstepping our boundaries—we'll offer to take the casket and free up the family members.

Interwoven Legacies

When Black Men of Labor first started, we came out of the Treme Music Hall, on the corner of Ursulines and North Robertson in Tremé, which was owned by one of our members, Mark Cerf. After a few years, I asked Paul Sylvester if we could bring the parade to Sweet Lorraine’s. He and I go way back because he was one of the few people who photographed the making of the Mardi Gras Indian suits on the Yellow Pocahontas side. His mom, Lorraine, had bars on Claiborne, and she also sponsored a baseball league that was always named Sweet Lorraine’s. When he opened up his club, he just picked up where his mom left off and kept the name.

Paul lets us paint the building and put up the sign. We’ve done that so much until people think it's our building. We took the banner concept and turned it into a flag. Every year, we make a new one, and the flags hanging from Sweet Lorraine’s is a representation of the years we paraded.

We had so many creative people in Tamborine and Fan that we’ve stayed close with, and their work is woven through Black Men of Labor. Melvin Reed was the master designer for the Yellow Pocahontas and also made the artwork for the Bucket Men parades. Doug Redd, an artist who left from us too soon, did the flyers and other artwork for Tamborine and Fan, and designed our logo, which is a treble clef, and Douglas Redd did the artwork to bring it to perfection. Once you came to know his work, you could immediately distinguish it. It had its own definition, kind of like Aretha Franklin. If you heard Aretha sing once, wherever you heard her, you’d know. Ashé let us use the ankhs that he made for our parade. And every year, we hire Eric Waters to be our official photographer. I've been rolling with Eric for 40 years. He was one of the basketball coaches with Tamborine and Fan, and he did a lot of accountant work for the organization before he moved to photography.

When you produce something like a second line, you have so many photographers who follow you, and they have the right to photograph all of what they want when you're in the public domain. We realized early on is that we couldn't stop them, but we could make certain that from beginning to end we had our own personal photographer who would not turn around and try to sell us our own photographs.

Another photographer, L.J. Goldstein, came in and said, “Hey man, I want to do some pro bono photography.” He wanted to shoot our group in a black and white format, which turned out to be very ingenious and very historic. It was another example of a collaboration between a photographer and their subjects. We wore a beautiful pair of butterfly shoes we had made, and it started to rain while we were parading. We kept going, but it rained.

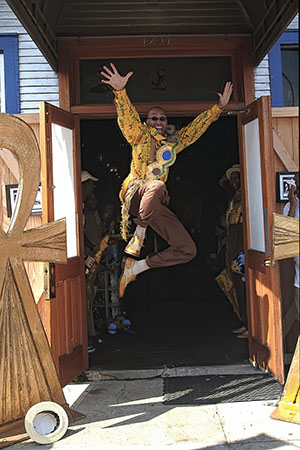

Coming out that door is the beginning of getting close to the end. By the time you come out that door, all kind of shit done went down. In 2015, the damn shoes we got on were made in Spain. They had to come through customs, and it was relief we got them in time because customs can jack you up for anything.

One year, we had two boxes of shoes. Customs kept one box in Cincinnati, the other box they sent to New Orleans. We’re a few days out from our parade. New Orleans tells us they can’t release the box until Cincinnati releases their box. Cincinnati says, “Well, it’s going to take us seven days to get you the box.” Now the parade is in three days. I call one of our friends, Waldo Jeff, and ask him if we buy him a ticket, if he will fly the box back to New Orleans. Don't ship the box because we don't have time for misstep. When he picks the box up from Cincinnati, New Orleans releases the box, and we are able to get the shoes in time.

Another year, we bought hats and one of the dude’s workers sent the hats the slowest way they could get here. Hats arrived two weeks after the parade. But a lot of it comes from members taking time to pay their money. In the lead up to the parade, we got to make sure we can get Melvin as much raw material to work with. If we leave it to him to go to the local places to buy materials, the price is going to be tenfold. To avoid last minute issues, everybody in the parade got to pay all their money full and up front. If you give yourself 90-120 days, you got enough time to conveniently make orders, receive orders. You're not up against the wire, and it reduces the stress level because it's a lot of work.

Coming out that door is 50% relief. Now, we’ve got to go through the street and go back in that door with everybody. That’s the other 50%. I grand marshal because you’ve got to blow the whistle to get 15-20 men to move together. When we get out the door, the crowd is thick. Everybody knows we’ve got to move, but until we can keep it moving, everybody wants to get as many shots as they can get—not just the professional photographers, but everyone with a cell phone.

We take the Big Chief Allison “Tootie” Montana philosophy of always trying to beat yourself. From year to year, we go from one end of the color spectrum to the other and keep the color moving. Mr. Ed Harrison, the brother of Big Chief Donald Harrison, Sr. of the Guardians of the Flames tribe, checked us out. He owned taxicabs and was very familiar with the parades. He said, “Hey man, I like how y’all do this,” and joined our club. Ed was old school. He was from that era when you wore stickpins, and if you didn't have diamonds on, you weren't dressed. Yeah, he had damn near a diamond on every finger. For our parades, he always wanted me to make him a big four-inch belt—a belt that couldn't even fit through the belt loops—to match the shoes.

After Katrina, we changed our parade date to October. At first, we had to parade on a Saturday, but eventually got our own Sunday. Everyone really looked forward to the Labor Day parade, and we cats started talking about, “What else can we do to honor Danny Barker”? I said, “Well, do the same thing he did with the Fairview Baptist Church band—keep pulling young people in. Even if they don't stay in the tradition, at least give them the foundation of the tradition.” One of our members, Bruce “Sunpie” Barnes, worked with the New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park, and he started the Music for All Ages program for kids with the Treme Brass Band and other traditional brass bands.

On Saturdays, they learned how to play music by ear by sitting in with the bands. Each year for our parade, Benny let the kids play in our parade. They came dressed in black and white with the band cap. It makes all the difference in the world to have a beautiful presentation.

We wrote a book–a fantabulous book—about the art and music and culture with the Neighborhood Story Project called Talk That Music Talk: Passing on Brass Band Music the Traditional Way. The front cover is Kente cloth we brought back from Ghana.