Andrew Jackson’s presidency coincided with what one historian described as “the full flowering of American democracy.” His election particularly reflected the will and aspirations of thousands of Americans intent on pushing the boundaries of their country ever farther south and west. Not only Old Hickory was their champion, but he was also one of them. His inauguration set the tone: the doors of the White House were thrown open, in the words of Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, to “immense crowds of all sorts of people, from the highest and most polished down to the most vulgar and gross in the nation.”

The political historian Alexis de Tocqueville dismissed President Jackson as “a man of violent character and middling capacities”—an opinion no doubt colored by the Frenchman’s association with East Coast elites who were horrified by Jackson’s popularity. On the other hand, Josiah Quincy Jr., a prominent Bostonian charged with escorting President Jackson during a visit, found him to be “vigorously a gentleman in his high sense of honor and in the natural straightforward courtesies.” Quincy added that he was “not prepared to be favorably impressed with a man who was simply intolerable to the Brahmin caste of my native state.”

The popular and uncompromising former general served two turbulent terms as president. His firm stance against South Carolina’s 1832 attempt to avoid federally mandated tariffs, as well as his willingness to fight France over its failure to fulfill treaty obligations, earned the respect of friends and foes alike, but other policies overshadowed his successes. Old Hickory’s dismantling of the Second United States Bank, which he saw as elitist and unconstitutional, led to a split among his cabinet advisors and ultimately to congressional censure for alleged abuse of executive power. President Jackson’s attempts at federal reform, including streamlining government departments and replacing key administrators, ushered in a long tradition of political patronage that persists to this day.

For many people today, the removal of Native Americans from their ancestral lands in the Southeast to reservations west of the Mississippi remains Jackson’s most troubling presidential legacy. To be fair, the plan predated his administration by decades. Thomas Jefferson proposed essentially the same policy in 1803; it was one of his rationales for the Louisiana Purchase. But Jackson carried the plan into effect, and his close involvement in the removal is well documented in letters and documents of the era. Old Hickory did not necessarily hate Indians, as some historians have alleged, but he certainly saw their presence within the southern states as incompatible with a secure American empire.

Andrew Jackson / Magnanimous in Peace / Victorious in War

ca. 1829; roller print on cotton textile

The William C. Cook War of 1812 in the South Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, MSS 557, 2001-68-L.38

Jackson's fame by the time of his first election as president may even have eclipsed that of George Washington. This wallpaper print, likely produced in France, places Jackson in the pantheon of American presidents, but he is very much the central figure.

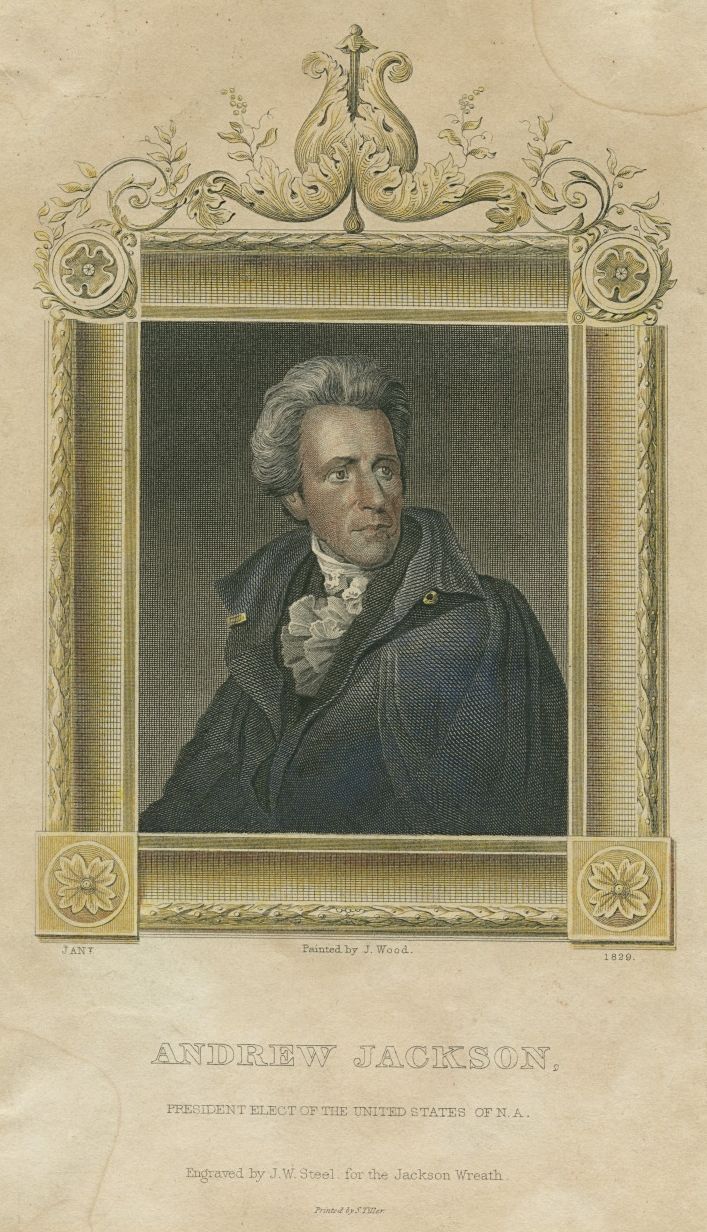

Andrew Jackson, President Elect of the United States of N.A.

1829; hand colored engraving

by James W. Steel, engraver, after Joseph Wood, artist

The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Harold Schilke and Boyd Cruise, 1959.183.7

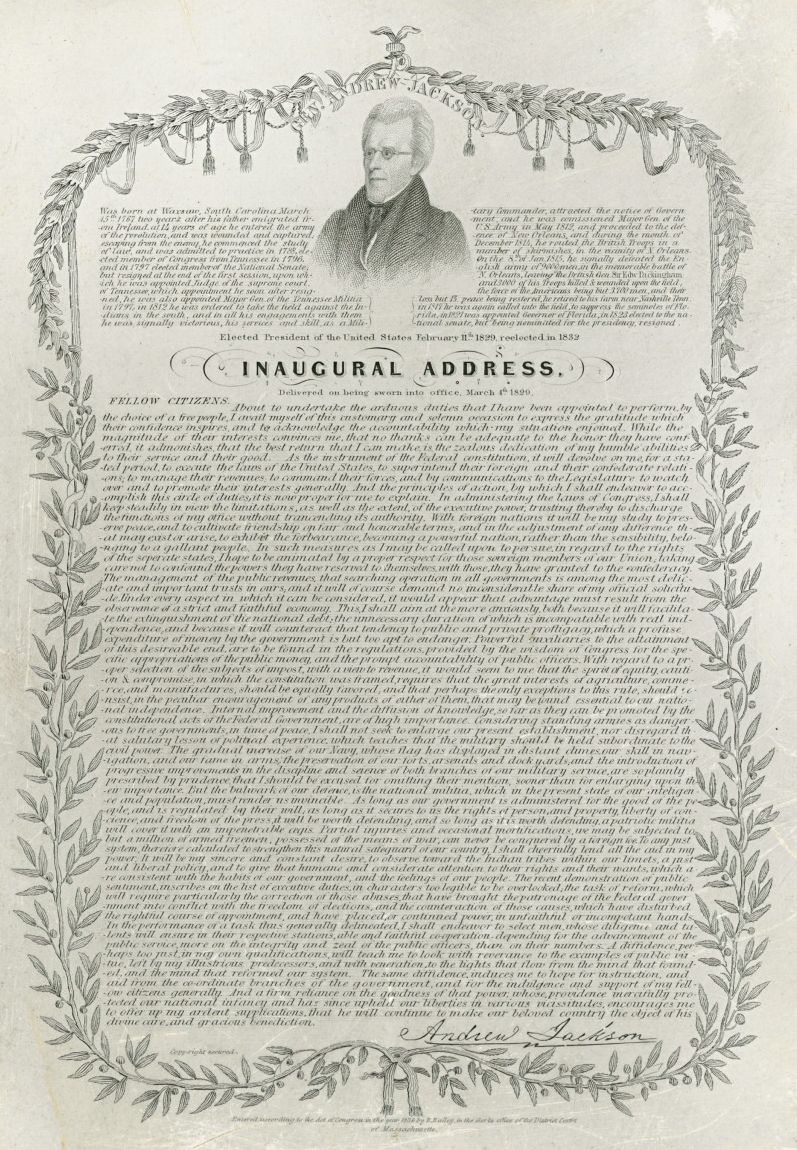

Souvenir copy of President Jackson’s first inaugural speech

ca. 1836; engraving

by Benjamin Bailey, engraver

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1957.66

President Jackson’s proclamation against the nullification ordinance of South Carolina

Washington, DC, 1832

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 59-77-L.8

Jackson firmly opposed South Carolina's argument that federal tariff laws with which they disagreed were null and void within the state's boundaries. As tensions grew to the point where secession was openly discussed, he pledged to keep the state in line by armed force if necessary. A compromise was eventually reached, but the so-called Nullification Crisis exposed deep divisions that presaged the eventual Civil War.

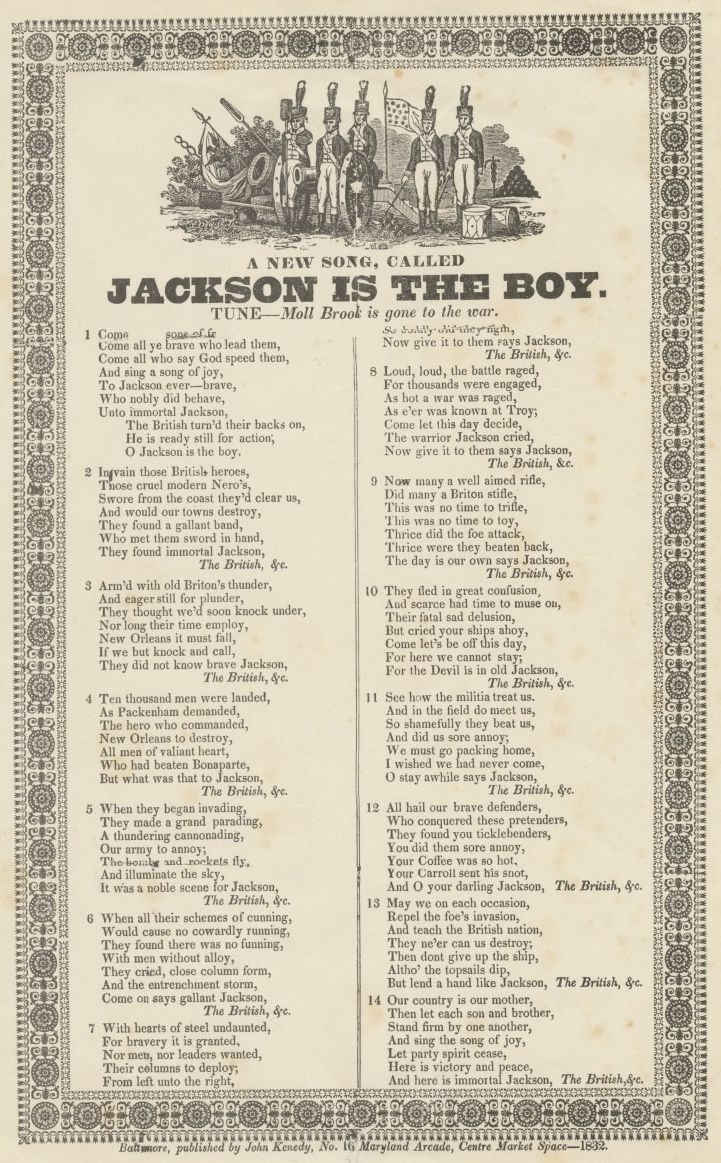

A New Song, Called Jackson Is the Boy

Baltimore: John Kenedy, 1832

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 86-2215-RL

This campaign song to promote Jackson's reelection in 1832 was intended to be sung to the tune of an older song called "Moll Brook Is Gone to the War." The Irish-born publisher John Kenedy had compiled The American Songster, a selection of 150 popular modern songs, in 1829; he produced subsequent editions in the 1830s.

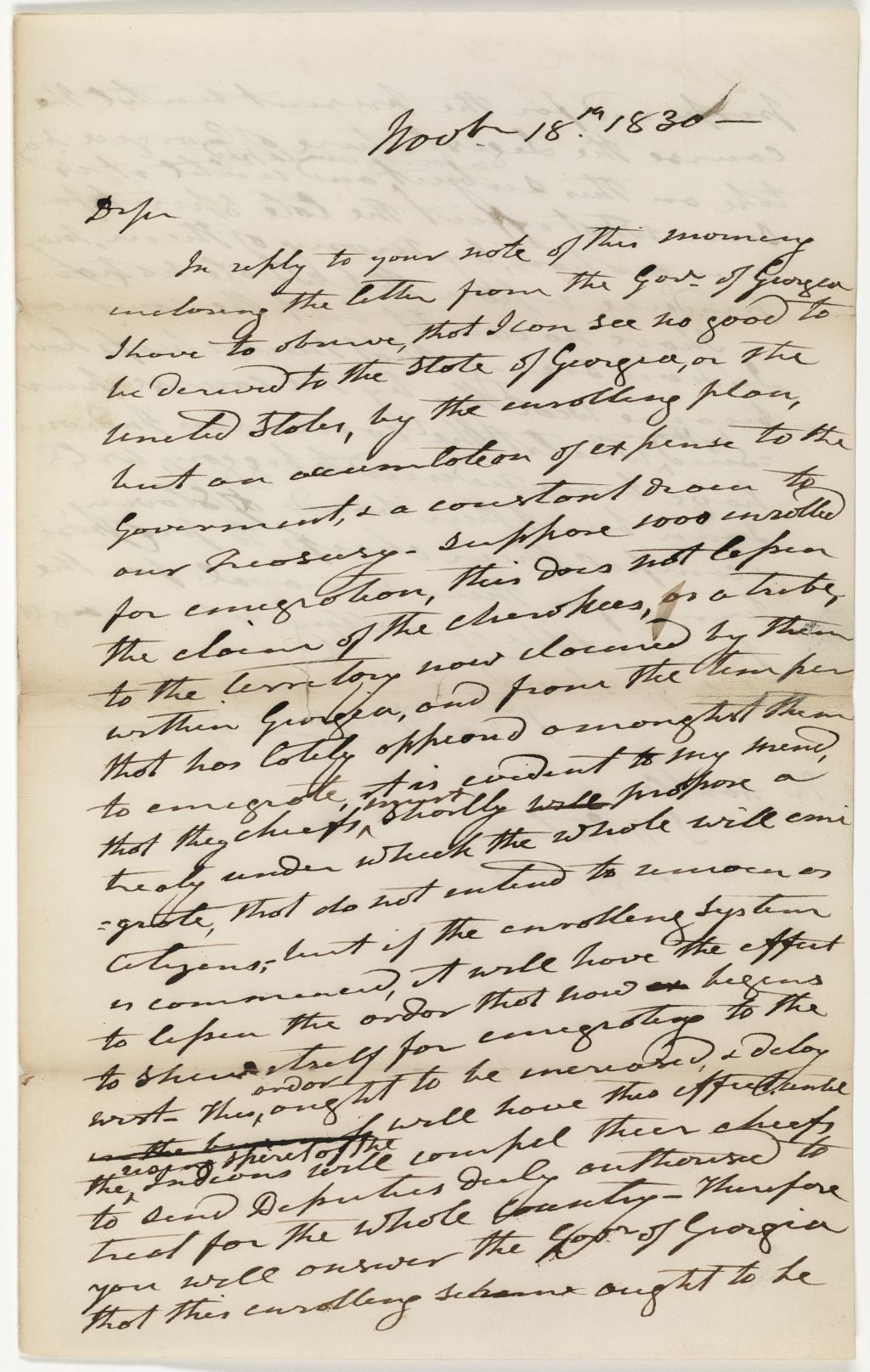

Letter from President Jackson to Secretary of War John Henry Eaton regarding the removal of the Cherokee from Georgia

November 18, 1830; manuscript letter

courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, 12199688

Jackson's administration removed federal protections for the Cherokee living in Georgia as part of an effort to force them to migrate west, beyond the Mississippi River. In the end, the Cherokee and Creek nations were pushed out of their ancestral lands in Georgia and Alabama via the infamous "Trail of Tears."

Andrew Jackson peace medal

between 1829 and 1837; silver

by Moritz Fürst, medalist

The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1968.41

European colonial powers began the tradition of issuing peace medals to Native American allies, and George Washington and later US presidents continued the practice until the late nineteenth century. These tokens were usually presented to chiefs or prominent tribal leaders on special occasions.

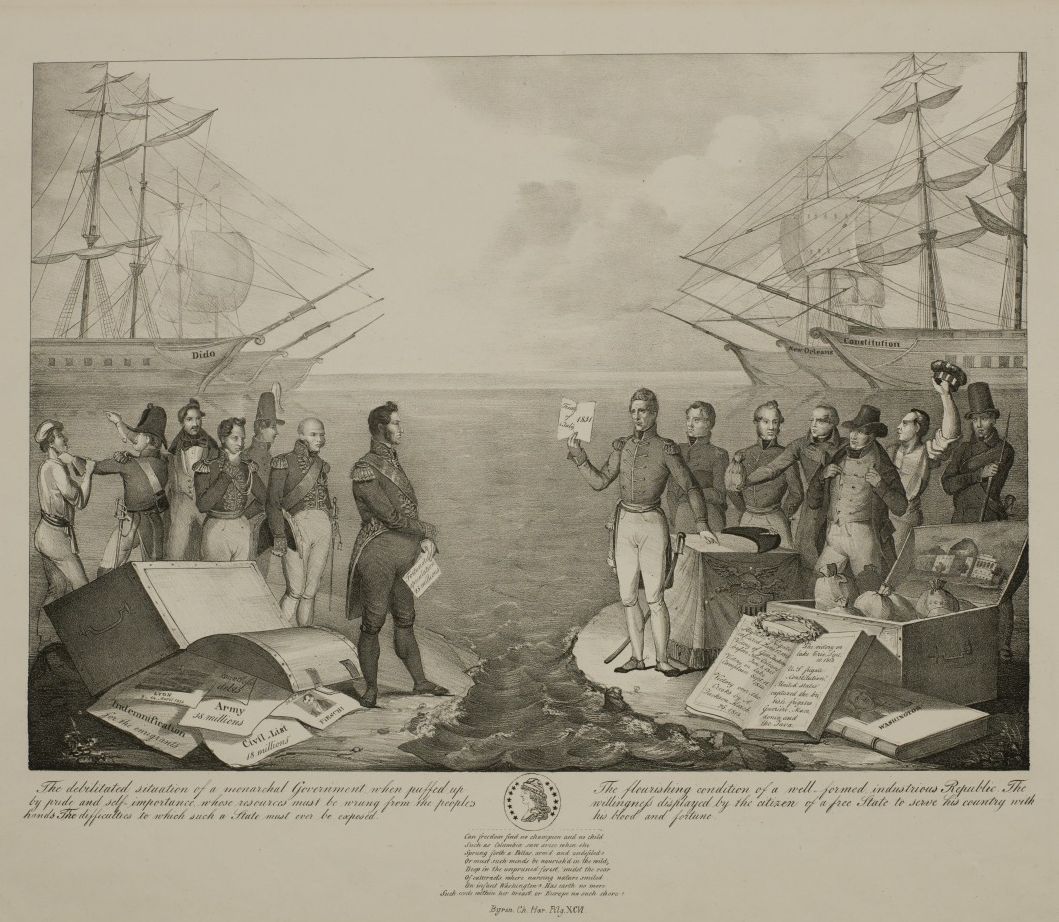

The Debilitated Situation of a Monarchal Government . . . The Flourishing Condition of a Well-Formed Industrious Republic . . .

1836; lithograph

The Historic New Orleans Collection, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1957.1

This printed view depicts a diplomatic rupture between the United States and France concerning multimillion-dollar claims against France for American ships seized during the Napoleonic Wars. A uniformed President Jackson holds the 1831 treaty obligating French payments, while the French king Louis Philippe holds a paper representing the amount owed, as other massive debts spill out of the overturned money chest behind him.

Qui paye ses dette s'enrichit

ca. 1836; lithograph

by Delaunois, lithographer

The Historic New Orleans Collection, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1957.65.1