Editor's note: We went deeper into the story behind the "Lost Friends" database and The Book of Lost Friends with author Lisa Wingate and THNOC volunteer Diane Plauché during a virtual program in June 2020. View the recording of the discussion here.

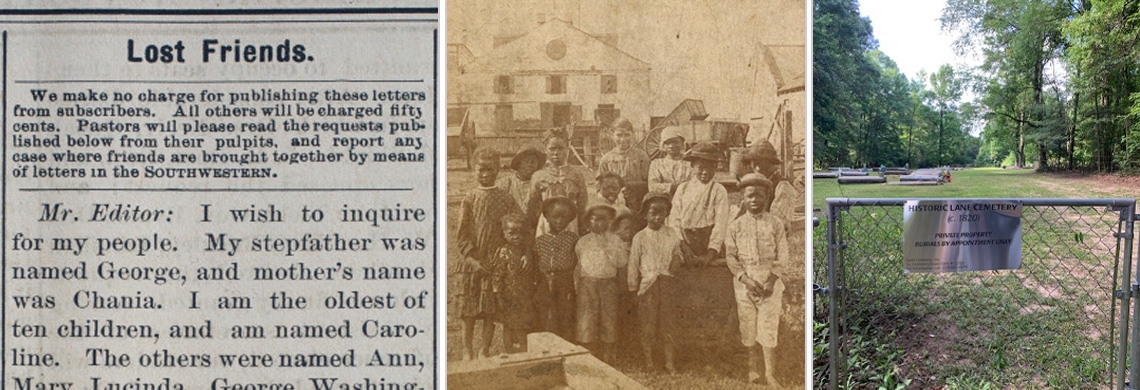

In 1892, 60-year-old Caroline Flowers placed an advertisement for the “Lost Friends” column of the Southwestern Christian Advocate, starting with a familiar line: “I wish to inquire for my people.”

In just a few column inches, she describes how, decades before, her mother, stepfather, and nine siblings, all enslaved at the time, were stolen from a Texas plantation and sold to different people across Mississippi and Louisiana. She and her siblings “were all my mother had when separated,” she writes, and she mentions all of them by name, as well as their enslavers. Her hope was that someone reading the column would recognize a name and help her to reunite with her loved ones nearly 30 years after the Civil War.

Caroline Flowers’s 1892 “Lost Friends” advertisement details how her mother and siblings were stolen and separated during slavery.

Caroline Flowers’s 1892 “Lost Friends” advertisement details how her mother and siblings were stolen and separated during slavery.

Flowers’s advertisement is one of thousands placed by formerly enslaved people ;who sought to piece together their families post-emancipation. Entries from the columns have been available online through The Historic New Orleans Collection’s “Lost Friends” database since 2015. Now, a new novel and a unique genealogical project are bringing fresh attention to the countless stories of separation and struggle all but forgotten in the tragedy of slavery.

At THNOC, work on the database began in preparation for the exhibition Purchased Lives: New Orleans and the Domestic Slave Trade, 1808–1865. Curator Erin M. Greenwald tapped THNOC volunteer Diane Plauché to help populate the database with names, places, and other details from each “Lost Friends” listing, which would bring the information—previously found only in hard copy or microfilm—into a searchable online format.

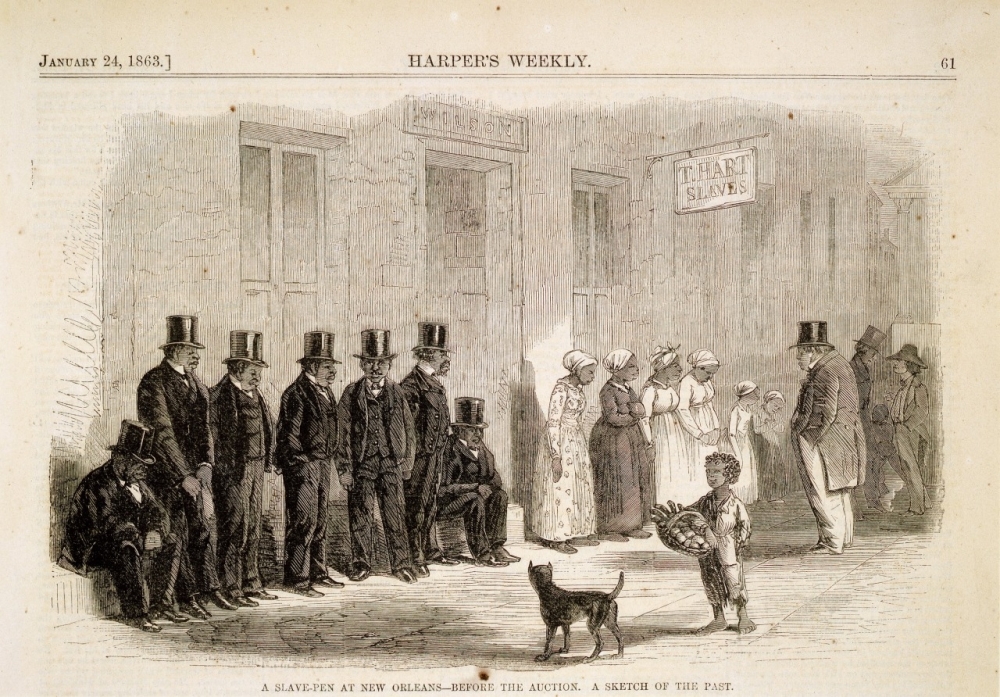

An 1863 illustration in Harper's Weekly shows enslaved people lined up prior to an auction. Families were often separated as part of the division of former enslavers’ estates. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1958.43.24)

An 1863 illustration in Harper's Weekly shows enslaved people lined up prior to an auction. Families were often separated as part of the division of former enslavers’ estates. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1958.43.24)

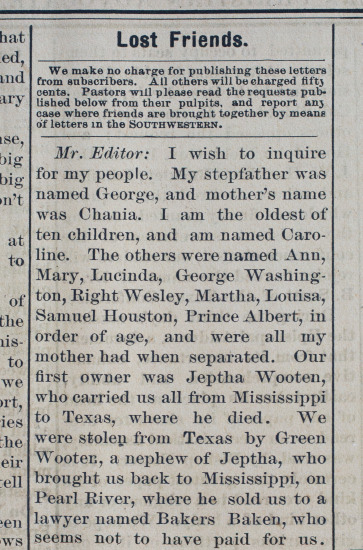

Plauché was familiar with genealogical research related to slavery. Her husband, Andy Plauché, has ancestors—the Lane family—who came to Louisiana from Maine before the Civil War and bought a cotton plantation in East Feliciana Parish, and the home has remained in his family.

In researching family letters, financial records, and other historical documents, Plauché was able to piece together details about the enslaved persons who lived, worked, and died on the plantation. From that research, she constructed a database that included names, birth and death years, and other details. Because a number of the descendants of the enslaved persons, including the present-day Miller family, remain in the area, Plauché embarked on a series of personal meetings to share her research.

Diane Plauché’s husband, Andy, has ancestors—the Lane family—who came from Maine before the Civil War and bought a cotton plantation in East Feliciana Parish, and the home has remained in his family. (Image courtesy of Amanda Plauché Jones)

Diane Plauché’s husband, Andy, has ancestors—the Lane family—who came from Maine before the Civil War and bought a cotton plantation in East Feliciana Parish, and the home has remained in his family. (Image courtesy of Amanda Plauché Jones)

These conversations led to a 1999 reunion, when about 80 descendants of both the Lane and Miller families gathered at the former plantation to reconnect and discuss their shared history.

In his column for the Miami Herald, Miller descendant Robert Steinback described how “exhilarating” it was to “witness how two families, put on very different tracks by history,” could, together, acknowledge the painful reality of their ancestry.

“The dark chapters of history customarily serve as wedges between families, peoples and races. It need not be so," Steinback wrote. "By throwing off what I’ve called ‘the arrogance of history’—the notion that accidents of fate that helped some families and hurt others were somehow ‘deserved’—history can be the glue that binds together all people of good will.”

Part of Plauché’s genealogical work helped identify the graves of people formerly enslaved on the plantation, as well as those of their descendants, who were buried near the Lane home. (Images courtesy of Diane Plauché)

Part of Plauché’s genealogical work helped identify the graves of people formerly enslaved on the plantation, as well as those of their descendants, who were buried near the Lane home. (Images courtesy of Diane Plauché)

Plauché took the experience into her work for The Historic New Orleans Collection, where she set out to index information from all 2,500 “Lost Friends” ads. She carefully read, and reread, each entry, obsessing over every detail so that they could be searched and potentially lead researchers or descendants to their stories.

"I could probably get through about 30 ads a day,” Plauché said, who worked with THNOC Photographer Melissa Carrier, Database Manager Lindsey Barnes, Digital Assets Manager Kent Woynowski, and Developer/Programmer Andy Forester to get the material online. “You don't just read the ad once; you have to read the ad six or seven times . . . so I would just have to shut it down and go breathe and walk around before I could get back on it again.”

Around the same time, Plauché was reading Lisa Wingate’s novel Before We Were Yours (Ballantine Books, 2017), a fictionalized account of the Tennessee Children’s Home Society, where, from the late 1920s until 1950, children were stolen from poor families and adopted out for profit. A line on the dedication page struck her as familiar: “For the hundreds who vanished and thousands who didn’t, may your stories not be forgotten.”

Plauché sent the author an email, urging her to look at the “Lost Friends” database. “There is a story in each one of the ads,” she wrote.

Wingate was not planning on starting a new project. She was on tour for Before We Were Yours and in the editing stages of another manuscript. Upon reading Plauché’s email, though, “I just ended up spending a lot of time tumbling down the well of these stories,” she said. “And I thought, every one of these is a family.”

Andy Plauché (left), Lisa Wingate (middle), and Diane Plauché (right) met at the Lane home after connecting over the “Lost Friends” ads. (Image courtesy of Diane Plauché)

Andy Plauché (left), Lisa Wingate (middle), and Diane Plauché (right) met at the Lane home after connecting over the “Lost Friends” ads. (Image courtesy of Diane Plauché)

She responded to Plauché’s email in less than a day, and from there, the two took up regular correspondence as Wingate dove deeper into the database. Her incomplete manuscript was still her next priority, but that changed when Plauché told her about Caroline Flowers.

While all “Lost Friends” advertisements tell stories that intertwine names and places, Flowers’s ad is especially detailed and follows a clear, horrific narrative of a family being ripped apart and scattered across multiple states. “Our first owner was Jeptha Wooten, who carried us all from Mississippi to Texas, where he died,” she writes. “We were stolen from Texas by Green Wooten, a nephew of Jeptha, who brought us back to Mississippi, on Pearl River, where he sold us to a lawyer named Bakers Baken, who seems not to have paid for us.”

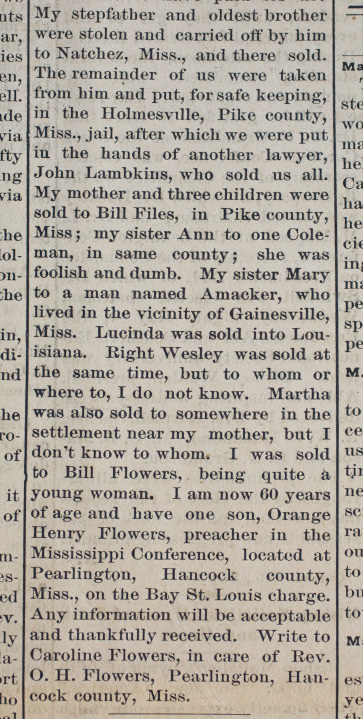

The second half of Flowers’s ad details where, and to whom, each of her family members was sold.

The second half of Flowers’s ad details where, and to whom, each of her family members was sold.

After reading Flowers’s words, Wingate stopped work on her manuscript and began writing a novel based on the advertisement. Called The Book of Lost Friends (Ballantine Books, 2020), it follows Hannie, a formerly enslaved woman who embarks on a journey with two unlikely travelling companions to trace the paths of her family members. The novel was published in April and debuted in the eighth spot on the New York Times Bestseller List.

“Once I could hear Hannie talking in my mind, I just had to go on and write,” said Wingate. “Sometimes stories just haunt you until you write them, and this was that kind of story.”

A second storyline follows Louisiana schoolteacher Bennie Silva in 1987, as she uncovers the century-old narrative of Hannie’s struggle through a cemetery near her rented apartment. Bennie and her students delve into the history and find relevance to their own lives. Wingate said she hopes the novel will help people become aware of “Lost Friends” so that they can find their own family histories.

“There are people out there carrying these names,” Wingate said. “And they may not know that they’re only a Google search away from finding them in the ‘Lost Friends’ database.”

This stereograph, taken between 1865 and 1895, shows African American children on the grounds of a plantation. (THNOC, 1979.221.13)

This stereograph, taken between 1865 and 1895, shows African American children on the grounds of a plantation. (THNOC, 1979.221.13)

These connections are already being discovered through the Georgetown Memory Project, which aims to identify the 300-plus individuals who were sold by Georgetown University in 1838. According to founder Richard Cellini, the project has made 230 identifications so far, thanks in part to the “Lost Friends” database. Beyond the nuts-and-bolts work of these efforts, Cellini said, the advertisements offer “incontrovertible proof of a point that should never have to be proven: the victims of antebellum US slavery were real people, with real names, and real families.

“These ads are the ultimate testimony to the strength, resilience, and resourcefulness of black families in America.”