The might of the Mississippi River has tested engineers for centuries. Few have approached its challenges more fearlessly than the self-taught James Buchanan Eads, who risked his career and even his life to exploit its potential.

Eads, whose family moved frequently until settling in St. Louis, worked as a clerk for a local merchant as a teenager and began his self-education reading from his employer's library. By 1842 the 22-year-old Eads had started his own business salvaging ships that had sunk in the river. He created a diving bell out of an open-ended barrel with an air hose that connected to a boat at the surface; it allowed him to descend to the bottom of the river in order to recover sunken goods that were previously unattainable due to the river’s strong current.

An 1880s photograph shows James Buchanan Eads shortly before his death. (THNOC, 1990.7)

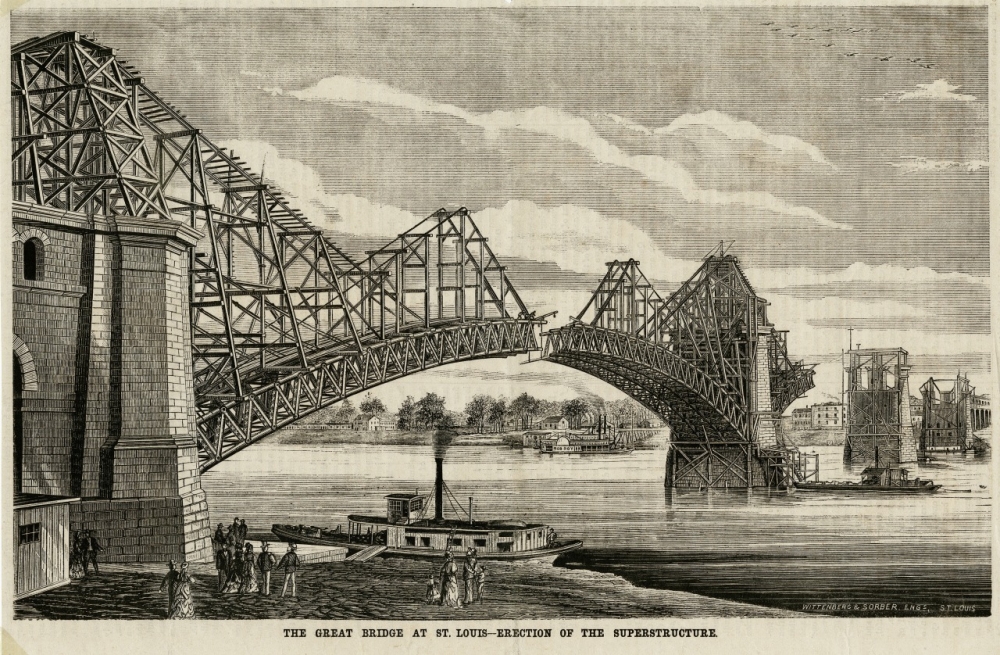

In 1867 Eads joined the St. Louis and Illinois Bridge Company as chief engineer with the task of building a bridge across the Mississippi River. His proposed design was unprecedented in many ways: it was the first to exclusively use steel—not yet a common building material—employ cantilevers, and carry railroad tracks. Eads faced criticism, particularly from Army Corps of Engineers Chief Andrew Humphreys, a formally trained civil engineer who became a rival of the autodidact. Despite this, Eads’s bridge officially opened in 1874 as the world’s first all-steel construction.

An 1874 wood engraving shows Eads's bridge across the Mississippi River in St. Louis, the world's first all-steel construction. (THNOC, 1974.25.30.750)

Eads’s next feat took him to New Orleans where, once again, his unconventional ideas were disputed by Humphreys. Downstream of the city, the mouth of the Mississippi frequently silted in and formed sandbars that prevented ships from sailing in and out of the river basin. Humphreys and the Corps of Engineers proposed to Congress that a canal be built between the river and Gulf of Mexico to bypass the sandbars; Eads advocated for the construction of jetties.

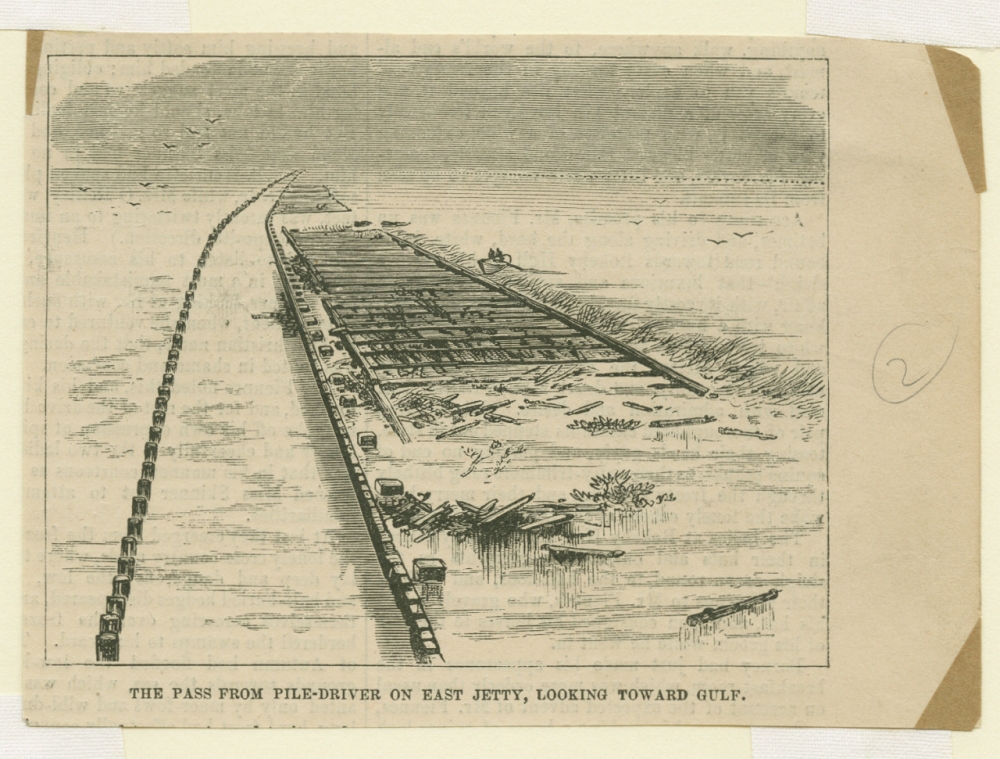

An 1877 engraving shows the east jetty at the mouth of the Mississippi River under construction. Eads's jetty design eventually won out over Andrew Humphreys's plan for a canal. (THNOC, 1974.25.17.194)

After several years of persuasion, Eads made a deal with Congress: he would build jetties at his own expense, and Congress would pay him only as the channel reached depth milestones, with the ultimate goal being 30 feet. Eads built two parallel piers far out into the Gulf to extend the east and west banks of South Pass, building up each jetty wall with willow “mattresses”—trunks of willow trees bound together, stacked, and held down with stones and concrete. The crevices would fill with sand and mud as the river flowed past them, rendering the jetties impermeable.

Eads’s jetties were completed in 1879, with a channel at the targeted depth of 30 feet, eliminating the silt buildup, and permanently opening the mouth of the Mississippi to ships. The new jetties exponentially increased the flow of commercial traffic through New Orleans.

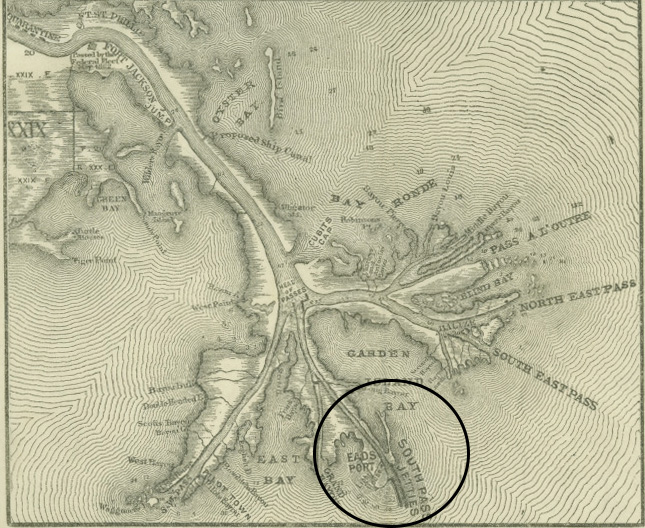

This map shows the location of the Eads jetties off of the South Pass of the Mississippi River delta. (THNOC, 1950.58.3 i)

Just a few years after completion of the jetties, Eads died at the age of 66. Today, the southernmost point in Louisiana, at the tip of the Mississippi River, is known as Port Eads, named after the man who died without knowing he had changed the course of the river's history.

A version of this article originally appeared in the Historically Speaking column of the New Orleans Advocate.

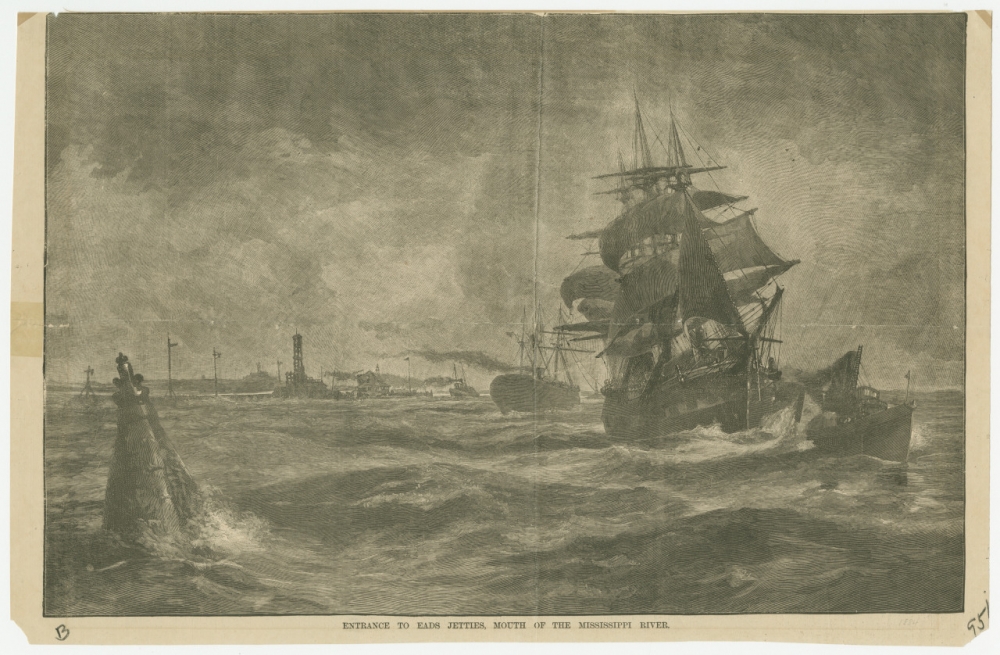

Cover image: A wood engraving shows the entrance to the Eads jetties in 1884. (THNOC, 1974.25.30.732)

Cover image: A wood engraving shows the entrance to the Eads jetties in 1884. (THNOC, 1974.25.30.732)