The World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition opened (two weeks late) on December 16, 1884, on the site of today’s Audubon Park. By that time, the 8th Cavalry Mexican Military Band (who arrived on time for the planned opening day) had already established itself as one of the exposition’s marquee attractions.

“If the [band’s] harmonies were full and perfect the melodious solos were equally delightful,” wrote the Daily Picayune of a pre-opening performance by the band. “When a platoon of flutes rendered a solo it was like a grove filled with the nightingales fluting their love music. One seldom hears music so feelingly and beautifully accented.

“Music lovers of New Orleans may be sure that they have a treat before them in the prospective performances of this really fine assemblage of musicians.”

The sensation created by the 76-member group, whose name was often shortened to Mexican Band, echoed throughout the near-six-month run of the exposition and beyond. Reconfigured assemblages of the 8th Cavalry Band as well as other Mexican bands were popular concertizers in New Orleans well into the next century. Compositions popularized by the band, such as "Lazos de Amor!" ("Links of Love!") and others, were featured in the catalogs of local sheet-music publishers.

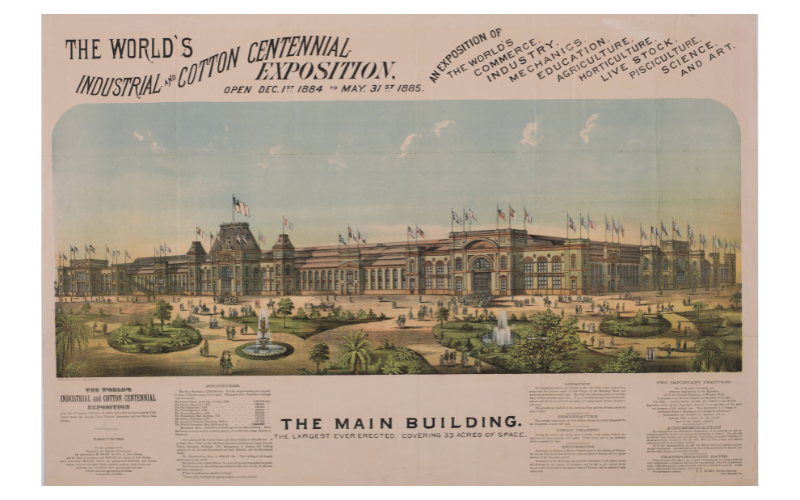

Promoted as “The Largest Ever Erected,” the Main Building of the 1884 and 1885 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans was built on the site that would later become Audubon Park. (THNOC, 1957.56)

Over and Over the Waves, one of three Prospect.5 installations on view at The Historic New Orleans Collection through January 23, 2022, recounts the Mexican Band’s triumphant 1884–85 visit to New Orleans as “a portal into bigger questions about the politics of migration and cultural exchange in contemporary New Orleans,” said Josh Kun, cultural historian and curator of the exhibition. Over and Over the Waves includes images and objects related to the Mexican Band’s exposition experience (many from THNOC’s holdings) as well as an audio installation built on piano renditions of some of the compositions the band popularized. The exhibition launched October 23, 2021, Prospect.5’s opening day, with a related musical performance at THNOC by trumpeter and composer Nicholas Payton and an ensemble of local musicians.

Here’s an edited interview with Kun:

Q: The Mexican Band New Orleans story is compelling in itself—especially considering the apparently ecstatic reception the band received from local press and concertgoers—but the musical elements tied to the exhibition, the sound mix in the gallery, and your collaboration with Nicholas Payton seem to elevate the installation beyond images and objects on the walls. How important was it to bring the band’s music to life in these ways?

A: It was crucial, foundational to the project. The story of the Mexican Band has been told many times, and archival materials related to their story have been exhibited before. My goal was not to do something strictly historical about the band, but to use their arrival in New Orleans in the late 19th century as a portal into bigger questions about the politics of migration and cultural exchange in contemporary New Orleans. What can the Mexican Band’s story tell us about how important migration has been to music in New Orleans? How does their story line up with histories of enslavement and the forced migration of Africans into New Orleans, but also with other contemporary histories of migration and displacement—from Garifuna, Honduran, and Vietnamese communities to Cameroonian detainees currently incarcerated in Louisiana detention centers? (I had originally planned a series of musical workshops with local refugee communities in partnership with the refugee services branch of the Catholic Charities Archdiocese of New Orleans, but the pandemic made sure that didn’t happen.) My practice is always rooted in animating the archives of the past to better understand the present.

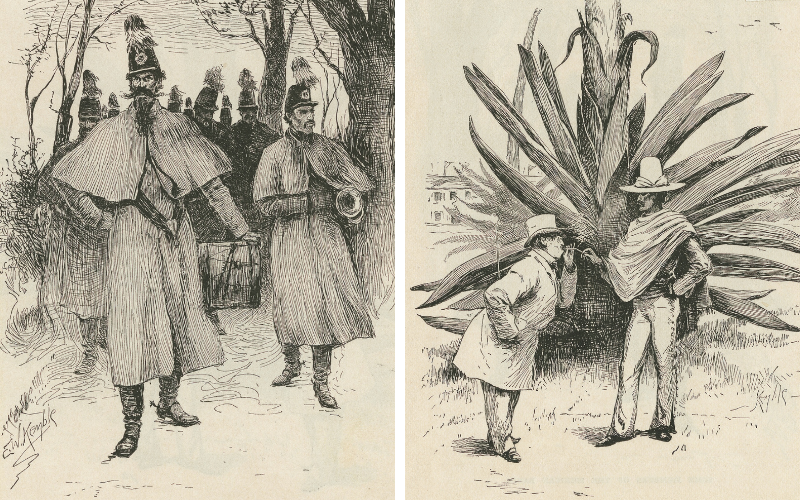

This wood engraving by Charles Upham, published in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, depicts Mexican officials, troops, citizens, and the 8th Cavalry Mexican Military Band at the inauguration of President Porfirio Díaz, which was held at the exposition. (THNOC, 1976.71.2)

Q: What was the nature of your collaboration with Nicholas Payton and the musicians performing the compositions? Will recordings of the music or local performances be made available?

A: I knew I wanted to assemble a band of New Orleans musicians with connections to these various histories of migration and diaspora, and I have long admired Nicholas’s work. His family has a deep history in New Orleans and also traces lineage back to the Garifuna in Honduras. I shared some of the band’s original sheet music with him, which inspired a new composition—a 30-minute suite he titled Bulbancha ’84—that speaks to these themes and histories and addresses themes of colonialism’s impact on indigenous cultures. For the band we are fortunate to also have Weedie Braimah, Oscar Rossignoli, Mahmoud Chouki, and Amina Scott, as well a collaboration with Mariachi Jalisco, an ensemble of Cuban musicians who are expert in Mexican mariachi. We will play one more show in January for the closing weekend of Prospect, and have begun dreaming about getting it recorded as well.

Q: How was the in-gallery sound mix composed?

A: I wanted to make a sound installation that would be in dialogue with the original archival materials from the 1880s and early 1900s, one that would, in a way, draw out new stories from them and maybe even change their meanings. I asked Oscar Rossignoli to play and record solo piano renderings of some of the original sheet music and then began sourcing archival audio and field recordings. Inspired by the famous Juventino Rosas composition “Sobre Las Olas” (“Over the Waves”)—associated with the Mexican Band—I created a sound bed of watery acoustics and then mixed different sounds, songs, and audio through the waves and ripples. In addition to music linked to Congo Square and early New Orleans brass bands, there is music and audio from refugee and migrant communities in Louisiana—Garifuna, Vietnamese, Central American, Mexican, Haitian, and Palestinian, among others.

Click on the video to hear an excerpt of the sound mix in cultural historian Josh Kun's Prospect.5 exhibition Over and Over the Waves. The images are sheet music of compositions popularized by the band. (Audio courtesy of Josh Kun; images courtesy of the Louisiana State University Libraries, Hill Memorial Library, Special Collections)

Q: When did you first discover the 8th Cavalry Band story? What drew you to the story?

A: I first learned of their story many years ago while researching materials for a class I was teaching on the history of American music. Since then, their story has appeared in scholarship by Gaye Theresa Johnson, Samuel Charters, Bruce Boyd Raeburn, and Raul Fernández, among others. I was very interested in how a Mexican band ended up in New Orleans in 1884 and how they influenced various musicians across the city. There has of course been much said about the so-called “Spanish Tinge” or “Latin Tinge” of music in New Orleans and I was fascinated by the role of Mexico in this wider set of African-derived Latin American influences.

Q: Why is this band’s contribution to New Orleans music history important?

A: Historians and critics continue to debate just how influential they actually were. My sense is that in the late 1800s and early 1900s there is no doubt they left their mark. Certainly, their popularity with local audiences, the number of shows they did, and the boom of “Mexican” and “Cuban” sheet-music publishing that circulated in New Orleans in their wake is a good indication of that. Some claim the band was responsible for introducing the saxophone to New Orleans, for example, or that members of the band became early influential music teachers in the city. But I also want to be careful to not overemphasize their influence on a city that was already profoundly rich in musical culture from Africa and the Caribbean.

Illustrations published in The Century Magazine in June 1885 depict activities associated with the exposition. The first image’s caption says, “Some members of the Mexican band.” The second, “Cactus from Mexico.” (THNOC, 1974.25.2.98 i,ii)

Q: What does the exhibition’s title mean?

A: As a play on Rosas’s “Over the Waves” composition, I wanted to call attention to the fact that movements over the waves (across the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, the Pacific, the Aegean, the Rio Grande) are ongoing, and urgent. Stories of movement—whether willful or coerced—happen over and over and over, and you can hear, for example, echoes of slave ships of the 16th and 17th centuries in the fatal waves of the contemporary Mediterranean that have witnessed the loss of so many migrants from across Africa. As I type there are thousands moving—fleeing, escaping—over the waves of our world.

Q: What’s one takeaway you’d like Over and Over the Waves visitors to have?

A: To leave with a heightened sense of migration’s multifaceted role in shaping contemporary New Orleans and in shaping the city’s singular music. To hear the city with an additional attunement toward contemporary displacement and flight. To hear the music produced by centuries of waves.