This video footage, shot by Jules Cahn, shows celebrations on the first day that the Audubon Park pool opened to all races. (Jules Cahn Collection at THNOC, 2000.78.4.375)

It was a hot June day in 1969, when for the first time, black and white kids dove into the Audubon Park swimming pool together, marking a symbolic victory for the civil rights movement in New Orleans.

Seven years earlier the pool had closed after a court order forced the park to integrate their swimming facilities. The park’s managers claimed that the pool had shuttered for financial reasons; it ran at a deficit and was too costly to repair. Called by the New Orleans States-Item “the largest in the South,” the massive facility had been a park landmark since it opened in 1928 to great fanfare. But it was only ever open to white children, and its empty shell remained, for some, a symbol of the city’s efforts to prolong segregation.

The Audubon Park pool seen here in 1928, shortly after it opened, was known for its immense size. It closed in 1962, the same year a court ordered the park to integrate its swimming facilities. (The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.5771)

In the intervening years, the New Orleans Recreation Department had systematically reopened public pools that had shuttered following orders to integrate, but swimming facilities became so overwhelmed that they had to implement a platoon system, allowing groups of children to cool off in the brutal summer heat in waves. Still, the mammoth pool sat dry.

Then came 1968. In the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination on April 4, civil unrest exacerbated racial tensions in cities across the country. Amid the uncertainty, local newspapers announced on April 18 that a committee of black and white citizens had come together to lobby for the reopening of the pool in Audubon Park. The 50-member group of business and civic leaders called themselves the Committee for Open Pools (COP). They named an African-American man, Robert P. McFarland, as chairman, and the committee’s message immediately garnered support from public figures like Congressman Hale Boggs and State Representative Ernest “Dutch” Morial.

Two scrapbooks from the COP—view one here, and the other here—reside in The Historic New Orleans Collection’s Williams Research Center. The scrapbooks contain snapshots, news clippings, and official correspondence from the organization, chronicling the events from King’s assassination to the pool’s eventual reopening.

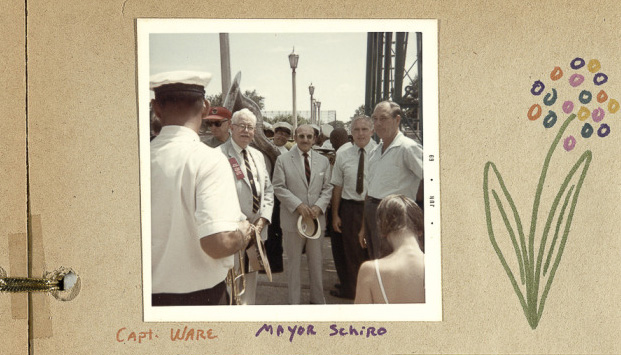

Snapshots taken in 1968 and 1969 cover the efforts of black and white citizens who championed the reopening of an integrated pool. (THNOC, 98-75-L.2)

Though the COP attracted public support overnight, progress in achieving their goal was not immediate. Audubon Park officials agreed that the pool should be opened, but claimed that they did not have the money to revive the landmark. Mayor Victor Schiro and city officials pledged their support to reopening the pool, but after an initial estimate outlined $430,000 worth of repairs, enthusiasm cooled. The committee solicited their own estimate, which came to around $50,000, and pushed the city to open the pool by the end of summer.

Reporter Jim Manning, writing in the States-Item, alluded to the fraught environment surrounding the issue, noting “the uneasy fear that hot weather will bring racial tensions as it has in so many other cities around the nation." He went on to say that “Everyone now agrees there should be swimming. But there are grave divisions over how and where.”

While the COP argued with officials over obstacles to repairing the facility, Schiro and the city attempted to solve the problem of the city’s overcrowded pools. The first solution, favored by the mayor, was to turn part of the shore of Lake Pontchartrain, near the Seabrook Bridge, into a swimming area. Trucks would deposit sand near the mouth of the Industrial Canal, and buses would convey swimmers to the beach from all over the city.

Swimmers await the ribbon to be cut at the pool's opening ceremony on June 8, 1969. (TNNOC, 98-75-L.2)

McFarland, who served as the COP's chairman, and others argued that the mayor’s solution would only prolong segregation: “I see this as an attempt to sanctify the current segregation at the Industrial Canal spot,” McFarland told the States-Item. “Negroes have traditionally used that beach, and this is merely an attempt to perpetuate that situation. White people probably won’t go.”

In addition to the geographical concerns, Lake Pontchartrain was notoriously polluted and had been closed to swimmers for 96 days the previous summer.

The States-Item responded to the plan with an editorial that accused Schiro and his administration of “calculated foot dragging.” One of Schiro’s aides and an engineering consultant shot back with letters to the editor accusing the newspaper of misinformation.

New Orleans Mayor Victor Schiro, center, is shown on the pool's opening day with members of the Committee for Open Pools. (THNOC, 98-75-L.1)

As the parties fought each other in the newspapers, the COP kept writing public officials, including Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who dispatched a representative to help the committee coordinate. The committee also sent out correspondence to supporters, labeling the dry Audubon Pool a “monument to segregation.”

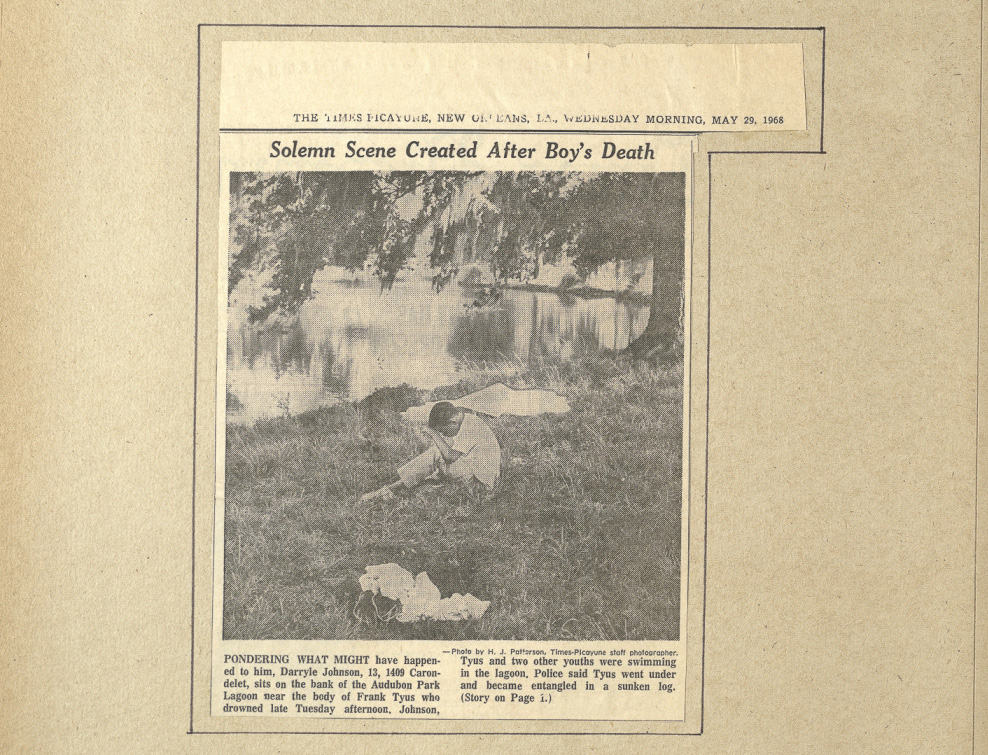

Then, after just over a month of back and forth, tragedy struck. A 15-year-old boy named Frank Tyus drowned in an Audubon Park lagoon on May 28. The next morning, after a meeting with COP officials, Schiro pledged to see the Audubon Pool reopened. The States-Item reported that, in the meeting, the committee had labeled the pool’s continuous closure “monstrous,” in light of the incident.

One of the scrapbooks contains a clipping from the Times-Picayune covering the death of Frank Tyus, a 15-year-old boy who drowned in an Audubon Park lagoon. (THNOC, 98-75-L.1)

The COP continued to press city officials throughout June and July, in an effort to get the pool open by Labor Day. In keeping with spirit of the civil rights era, the group even wrote a protest anthem called the “Pool Song” to be sung by supporters of the cause. In a letter to Schiro, the committee urged the city to act, labeling the dry pool “a festering sore on the body politic, which might erupt at any time dealing death to whatever hope now remains for racial peace.”

On July 22, Schiro announced that the pool would reopen in six weeks. To ferry the process, the mayor put City Councilman Moon Landrieu in charge of preparing the facility for swimmers; however, the high cost and volume of repairs kept the facility shuttered until the following summer. Still, committee members monitored Schiro, Landrieu, and others to see that the city signed a lease with the park agreeing to pay annual rent of $1 and allotted money for the rehabilitation of the facility in the 1969 budget.

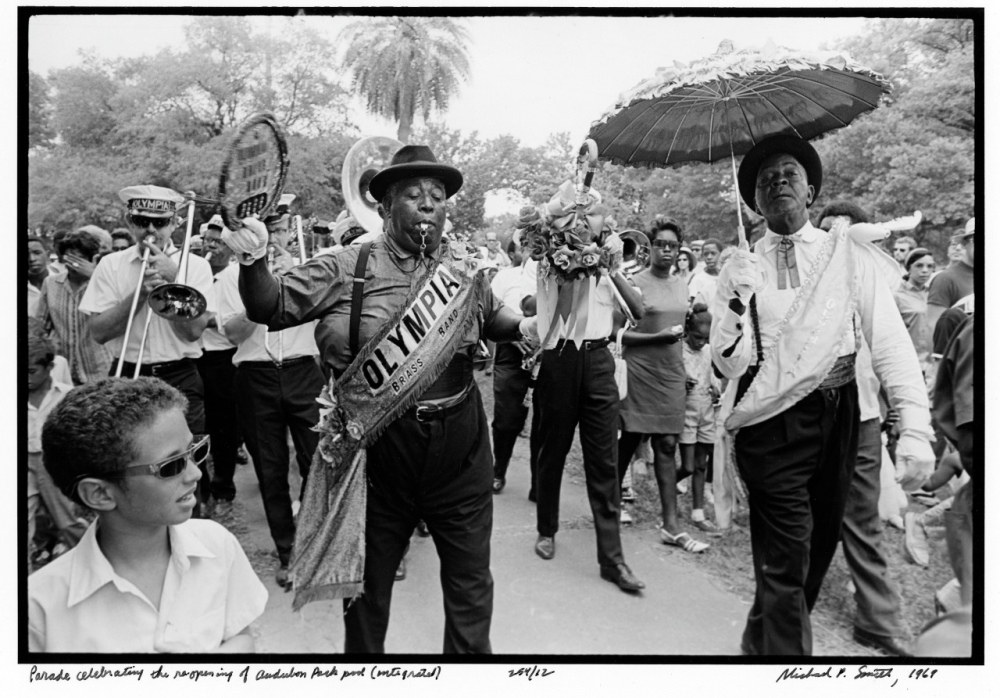

Photographer Michael P. Smith captured this image of the Olympia Brass Band at the Audubon Pool “Splash-in” on June 8, 1969. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith ©THNOC, 2007.0103.2.152)

Finally, on June 8, 1969, Schiro, Landrieu, city officials, and COP members gathered at the pool, which welcomed over 1,000 kids of all races for a “Splash-in” to commemorate the reopening. In a video captured by Jules Cahn, you can see Schiro cutting a ribbon, finally opening the pool after seven years of closure. The opening celebration also included brass bands that brought a festive atmosphere to this symbolic move toward racial equality.

Fifty years later, the giant pool is now gone. Closed in 1992, and removed later that decade, the “largest pool in the South” was replaced by a smaller natatorium in 1998.

The Committee for Open Pools scrapbooks are available to researchers at THNOC's Williams Research Center, which is open to the public Tuesday–Saturday. Admission is free, and visitors do not need to make an appointment.