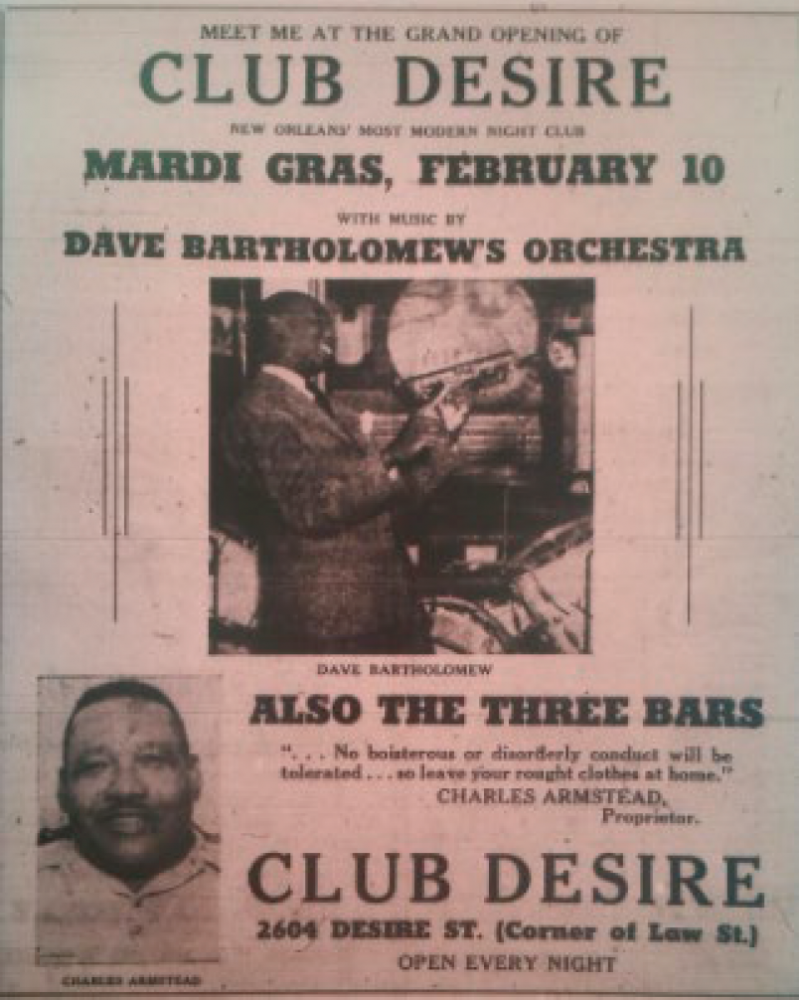

No ordinary day would suit the grand opening of Charley Armstead’s Club Desire in 1948: it had to be Mardi Gras.

The ambitious proprietor made sure that his palatial Ninth Ward nightclub stood out even on New Orleans’s most festive day, booking Dave Bartholomew’s Orchestra for the first night, placing advertisements in the Louisiana Weekly, sending trucks with music and loudspeakers into the neighborhood, and illuminating the night sky with klieg lights that could be seen for 20 miles. In an era when the city’s premier music venues excluded Black patrons, Armstead set the tone from the beginning, determined to make his establishment a cornerstone of the community and an essential stop for some of the country’s most renowned Black performers. In the 2020 documentary The Untold Story of Club Desire: A Musical Treasure, Armstead’s granddaughter Dana Royster-Buefort explained the club’s stature: “Harlem had the Apollo; New Orleans had Club Desire.”

A flier promoting Club Desire’s grand opening on Mardi Gras night, 1948. (THNOC, gift of Jeramé J. Cramer, 2021.0003.1.2)

The Historic New Orleans Collection recently acquired the 28-minute documentary and a number of other Club Desire materials from FEMA, which commissioned the film as part of its effort to commemorate the building’s significance prior to its demolition in 2016. THNOC and the Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans will co-present a free virtual screening of The Untold Story of Club Desire featuring THNOC curator/historian Eric Seiferth, Royster-Beufort, and music historian Rick Coleman on Wednesday, September 7, at 6:30 p.m. (Register here.)

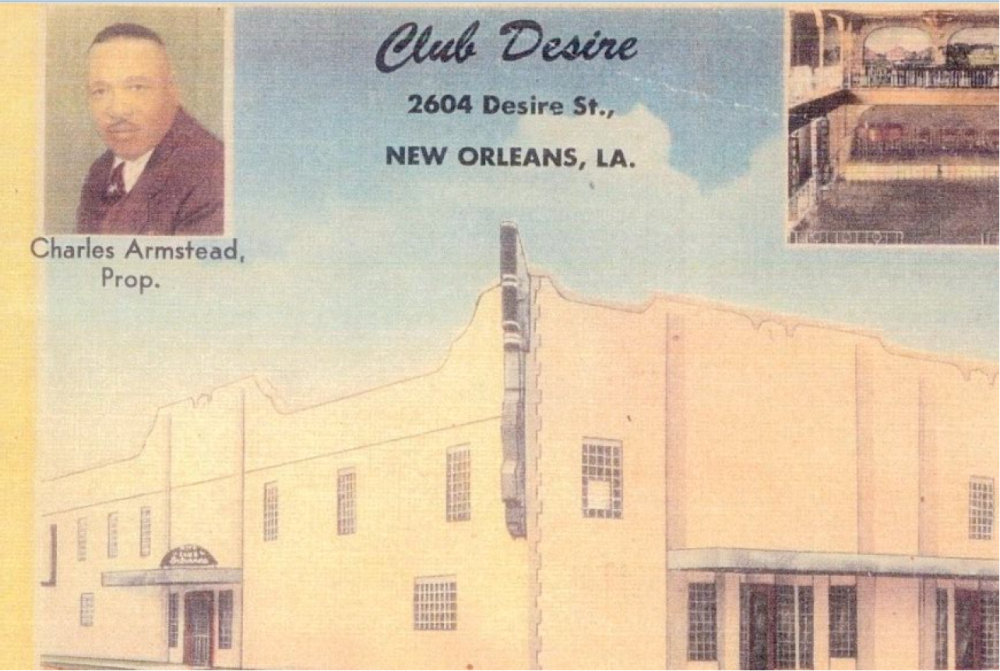

Above the reception-area bar at Club Desire, located at 2604 Desire Street, hung a sign that read, “Club Desire: The Downtown Club with Uptown Ideas.” The sprawling, two-story venue could host up to 1,000 guests. Armstead aspired to create a place that embodied modernity and luxury—featuring details such as European landscape murals and walls made of glass bricks imported from Japan—that remained accessible to the types of working-class Black New Orleanians who lived in the neighborhood. It proudly served as a destination for Black people to dress up in their finest suits and evening gowns, dance and enjoy live music and performances, and dine on everything from boiled crabs to trout meunière at white-linen balcony tables overlooking the main floor.

Club Desire brought marquee acts and modern luxuries to the heart of the Ninth Ward. Upscale details included glass bricks Armstead imported from Japan, which can be seen in the windows and lobbies portrayed on this postcard. (THNOC, gift of Jeramé J. Cramer, 2021.0003.1.2)

It was also an attraction for the performers themselves, playing a formative role in the development of a number of artists’ careers, including Bartholomew, Fats Domino, and Ray Charles. In the late 1940s Domino played in Billy Diamond’s Band, which, like Bartholomew’s band, had a residency at Club Desire. The club gave Domino the space to experiment with techniques such as his piano triplets, which featured in his 1950 hit, “Every Night About This Time,” and became a signature part of his sound.

Dave Bartholomew (left) and Fats Domino (right), seen here in 1957, got some of their earliest breaks performing at Club Desire, before going on to form a highly successful musical partnership. (THNOC, 1994.94.2.2283)

“It’s during these years, specifically during Charles Armstead’s ownership from 1948 to ’54, that rhythm and blues begins to emerge as a nationally popular style, contributing to the development of rock and roll,” Seiferth said. “Club Desire was part of the fabric of an emerging music scene in New Orleans that eventually would influence musical styles and tastes across the country.”

One of Ray Charles’s first appearances in New Orleans, possibly the very first, came at Club Desire in 1951, when he opened for vocalist and guitarist Lowell Fulson. Charles performed at the club again in 1952. Other musicians that Armstead brought in included Count Basie, Billy Eckstine, Mercer Ellington, and Percy Mayfield, along with a variety of other performers including comedians, female impersonators, acrobats, dancers, and more. Armstead died in 1954 and his oldest daughter, Audrey, a fashion designer who held shows in the club, took over. It remained a popular draw into the 1960s. Ownership changed hands a few more times and the club stopped hosting major musical acts, but it remained a popular neighborhood bar for years.

Ray Charles, seen here performing at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival in 1995, had a deep connection to the Crescent City. His 1951 performance at Club Desire may have been his first in the city, and he played the venue again a year later. He also lived and performed at the Dew Drop Inn in Central City early in his career. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith © THNOC, 2007.0103.2.287)

Club Desire’s doors had long been closed by the time Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005. The storm severely damaged the vacant building, and despite efforts by community advocates and preservationists to save it, the city ultimately demolished it. In addition to the documentary, FEMA produced an illustrated history of the club and photographs of the structure prior to its demolition, all of which were donated to THNOC.

The vacant Club Desire building in 2008, eight years before its demolition. (THNOC, gift of Jeramé J. Cramer, 2021.0003.2.4)

“The Club Desire materials THNOC has added to its holdings will be valuable to historians and music researchers,” Seiferth said. “More than that, they help to preserve the story of an important musical landmark in the city and nation, and a space that served as a neighborhood anchor in the Ninth Ward for decades.”